Vagina

Cervix

aLow-risk HPV

aHigh-risk HPV

aLow-risk HPV

aHigh-risk HPV

LSIL

81

18, 51

6, 11

18

42, 43, 54, 62, 67

56, 66

16, 66

16, 39, 52, 58, 67

35, 51

31, 33, 45, 68

26, 39, 52, 53, 58, 59

HSIL

CP6108

16

None

16

58

31, 35

31

18

35, 51, 52, 66

58

52, 56, 59, 66, MM1, MM3

Unlike the cervix, the vagina (and vulva) lacks the squamocolumnar junction where HPV preferentially infects. This in part accounts for the lower frequency of VaIN compared with the cervical counterpart. HPV gains entry into the vaginal squamous epithelium through micro-openings, such as those secondary to microtrauma or erosion, and accesses and preferentially binds to the epithelial basement membrane before binding to the cell surface receptors and infecting basal cells [30, 31]. The microtrauma also induces wound healing and activates cell division in cells that are infected with HPV [32, 33]. At the same time, the virus undergoes DNA replication in these basal cells, but viral gene expression and protein production do not usually occur until the keratinocytes are differentiated and situated nearer to the surface of the epithelial layers in the stratum spinosum and granulosum. The duration of this infectious process is variable and takes at least 3 weeks. Subsequent integration of DNA into host genome is vital for neoplastic progression [34, 35]. It should be pointed out that even though HPV infection is necessary for neoplastic transformation, the majority of infection will resolve with time as it is usually cleared by the host’s immune system, specifically cell-mediated immune response. It is estimated that 70 % of the infection will resolve spontaneously within 1 year and about 90 % will resolve within 2 years [36–38]. Only persistent infection would result in an increased risk of deregulation of viral gene expression and neoplastic progression [39–41]. It is thought that the persistence is in part a result of suppression of the host innate and adaptive immune responses [40, 42, 43].

Other risk factors for VaIN are similar to those for CIN and contribute to an increased risk of HPV infection in the vagina . These include concurrent HPV infection of other lower genital sites, smoking (carcinogenic effect of tobacco), use of oral contraceptives, immunosuppression (including human immunodeficiency virus infection), and external pelvic radiotherapy for other malignancies [6, 16, 44–50]. Women who were exposed to in utero diethylstilbestrol (DES) have vaginal adenosis more frequently [51–53]. This results in greater number of squamocolumnar junctions resembling those in the cervical transformation zone which then becomes the targets for HPV infection and subsequent development of VaIN, squamous cell carcinoma, or adenocarcinoma [54–57].

Nomenclature

Traditionally, VaIN was classified using a three-tier system of VaIN I, II, or III according to the degree of dysplasia, similar to those described for the cervix. In agreement with the Bethesda System for Cytopathology and the 2013 LAST project recommendations, the WHO 2014 working group agreed to replace this traditional three-tier histologic classification of squamous intraepithelial neoplasia (i.e., VaIN I, II, and III) into a two-tier system of low- and high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (i.e., SIL, as LSIL or HSIL, respectively) [4, 58, 59]. The rationale for this change is that the two-tier system is more histologically reproducible than the three-tier system and can divide patients into two managerial or biological subgroups. Lesions regarded as condyloma and VaIN I are morphological manifestation of transient HPV infection and will be classified as LSILs . HSILs are a result of persistent infection by high-risk HPV, are precancerous, and will replace the VaIN II/III category.

Gross Features

Patients with either LSIL (condyloma and VaIN I ) or HSIL (VaIN II/III ) in the vagina are asymptomatic, and the lesions are usually grossly invisible. The usual presentation is an abnormal vaginal smear result. They may also be detected by colposcopy incidentally during investigation for abnormal cervical cytology. The lesions are represented by a white or pink discolored area with or without a raised plaque with irregular granular surface. They are usually more visible after application of acetic acid or Lugol’s iodine solution under colposcopy (Figs. 10.1 and 10.2). The upper third of the vagina is more frequently involved. About 50 % of lesions are multifocal, and in 75 %, there is a preceding or concurrent SIL or carcinoma in the cervix or vulva [6, 20, 24, 25, 60–63].

Fig. 10.1

VaIN I (LSIL) after application of 5 % acetic acid under colposcopy. Faint acetowhite areas in lateral vaginal wall with fine punctation and fine mosaicism (right)

Fig. 10.2

VaIN II/III (HSIL) after application of 5 % acetic acid under colposcopy. Dense acetowhite area with coarse punctation (1–2 o’clock)

Microscopic Features

SIL is characterized by various degrees of epithelial dysplasia but without invasion through the underlying basement membrane. The cells in SIL show nuclear atypia, partial loss of or disordered squamous cell maturation, dyskeratosis, and increase in mitotic activity, including the presence of atypical mitoses. LSIL (condyloma and VaIN I ) is diagnosed when the dysplastic epithelium involves the lower one-third of the epithelial layer (Fig. 10.3); koilocytic atypia is defined by nuclear enlargement with or without binucleation, nuclear membrane irregularity, hyperchromasia, and perinuclear halo. These HPV cytopathic effects are normally found in mature squamous cells (Fig. 10.4). HSIL (VaIN II/III ) is diagnosed when the involvement of the epithelial thickness exceeds that of LSIL (Figs. 10.5, 10.6, 10.7, and 10.8).

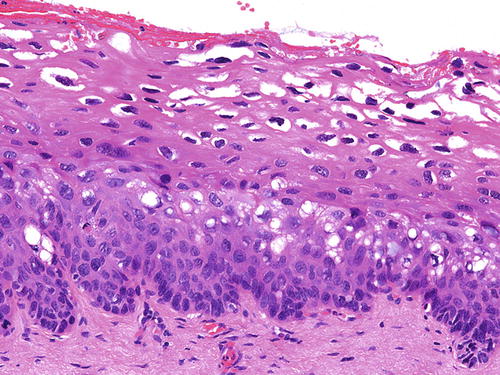

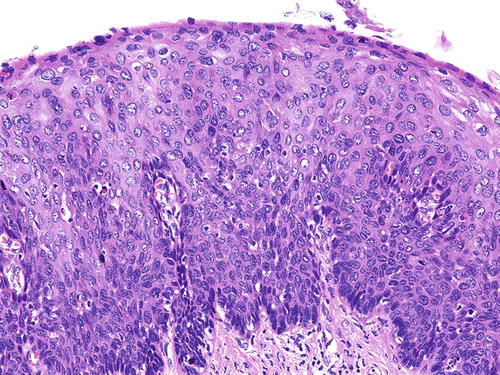

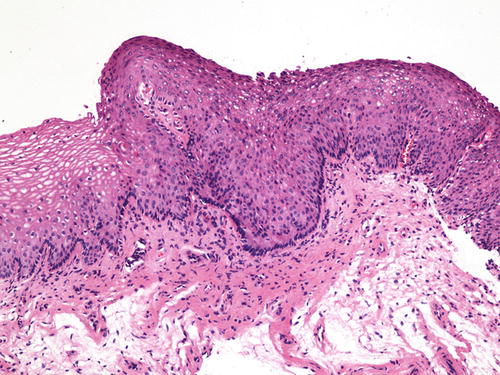

Fig. 10.3

VaIN I and condyloma (LSIL). Dysplastic epithelium involving the lower one-third of the epithelium. Typical koilocytes are striking in the upper, mature layers of the epithelium. H&E ×40

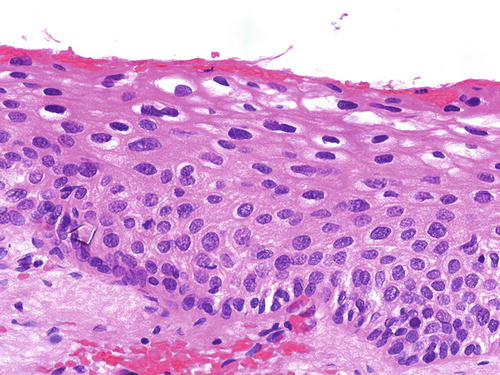

Fig. 10.4

Condyloma (LSIL). Mild epithelial dysplasia may be difficult to appreciate in thin and atrophic epithelium. There is minimal atypia involving the basal and parabasal cells, but koilocytes are more readily identified in the upper layers. H&E ×40

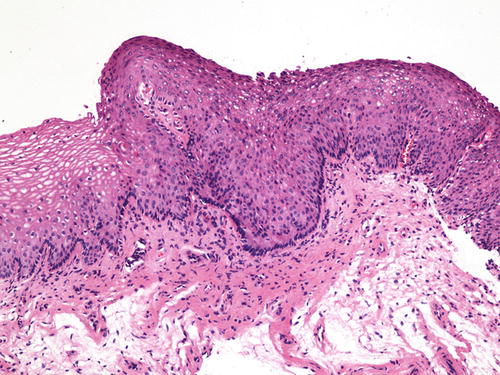

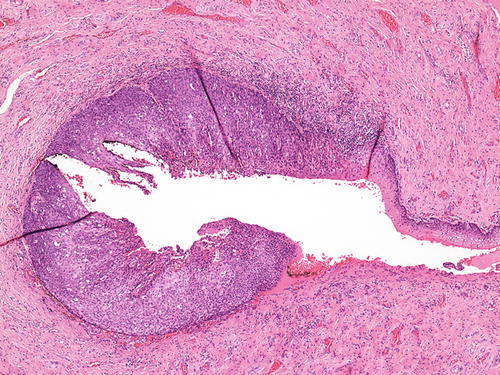

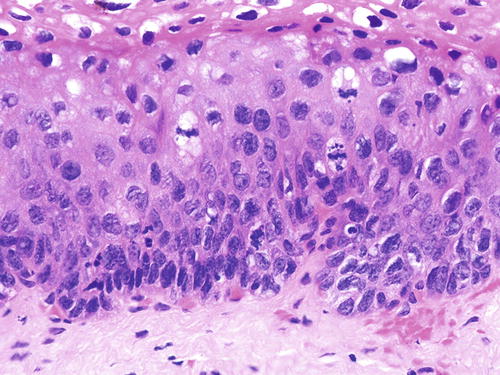

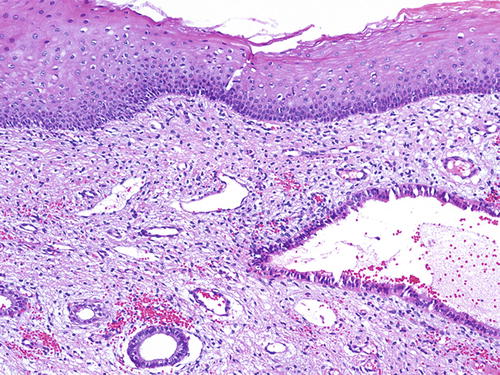

Fig. 10.5

VaIN II (HSIL). Focus of HSIL is usually well demarcated from the adjacent nondysplastic epithelium and can be appreciable under medium magnification. H&E ×20

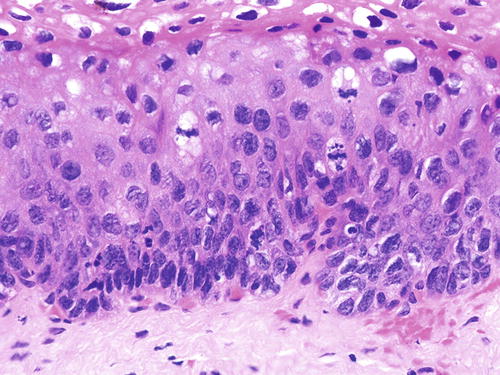

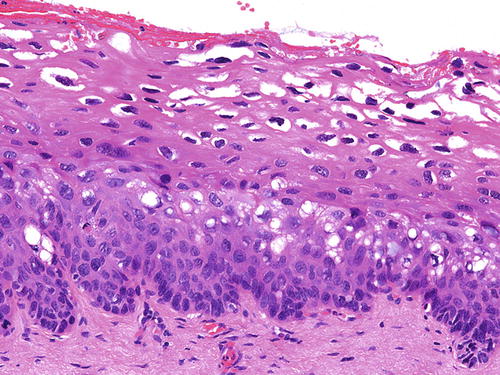

Fig. 10.6

VaIN II (HSIL). Dysplastic epithelium with mitotic figures involving the lower two-thirds of the epithelium. Limited maturation is preserved nearer to the surface. H&E ×40

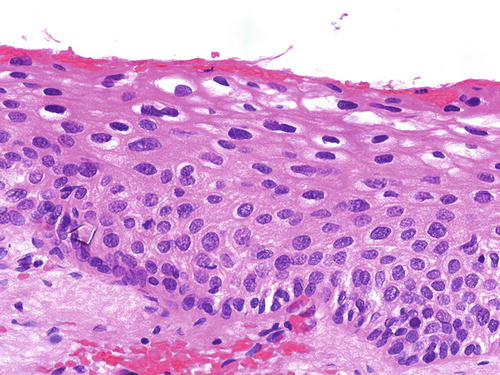

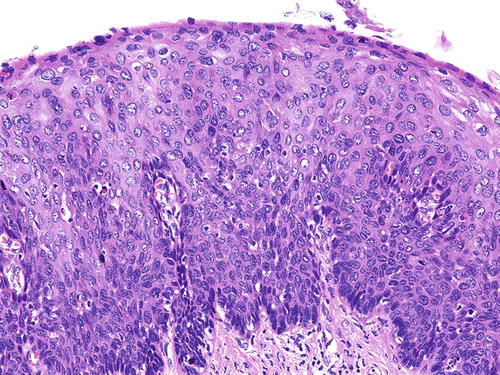

Fig. 10.7

VaIN III (HSIL). Full-thickness epithelial dysplasia. H&E ×20

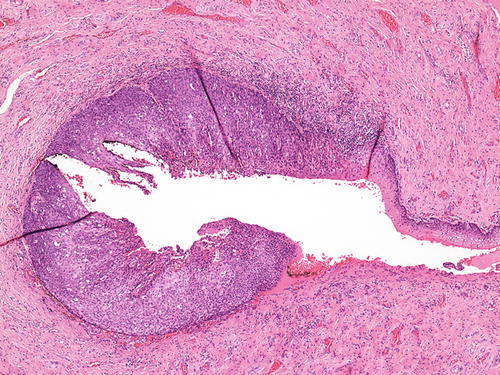

Fig. 10.8

A typical case of VaIN III (HSIL) involving the vaginal vault. The dysplastic focus (left upper and lower) shows sudden transition to normal (top right) and ulcerated mucosa (lower right). H&E ×10

Immunohistochemistry

p16

The LAST recommendation has determined that p16 immunostain is useful in routine pathologic diagnosis of SIL [64]. p16 is a cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor encoded by the tumor suppressor gene, CDKN2A. It arrests cell cycle by inactivation of the cdk4-cyclin D and cdk6-cyclin D complex, which controls the transition to S-phase by phosphorylation of Rb. Binding of HPV E7 to pRB essentially leads to its inactivation and causes an inverse rise in p16 protein [65]. This rise in p16 indirectly indicates the presence of high-risk HPV infection and can be detected by immunohistochemistry, especially when the staining is diffuse and strong [66–74]. This immunostain has been found to be useful in distinguishing HSIL (VaIN II/III ) from benign mimics (see below) but not from LSIL (condyloma and VaIN I ) as the latter have been shown to express p16 in up to 50 % of cases [66, 72–74]. It should also be noted that the frequency of p16 positivity in vaginal SIL is considerably less than that in the vulval and cervical counterparts (62 % of vaginal versus 85 % of vulval and 90 % of cervical HSILs) [75]. The LAST working group recommends the judicious use of p16 stain and that it should only be used to confirm a morphological impression of HSIL (VaIN II/III) but not used merely to distinguish between LSIL (condyloma and VaIN I) and HSIL (VaIN II/III) (Fig. 10.9) [4].

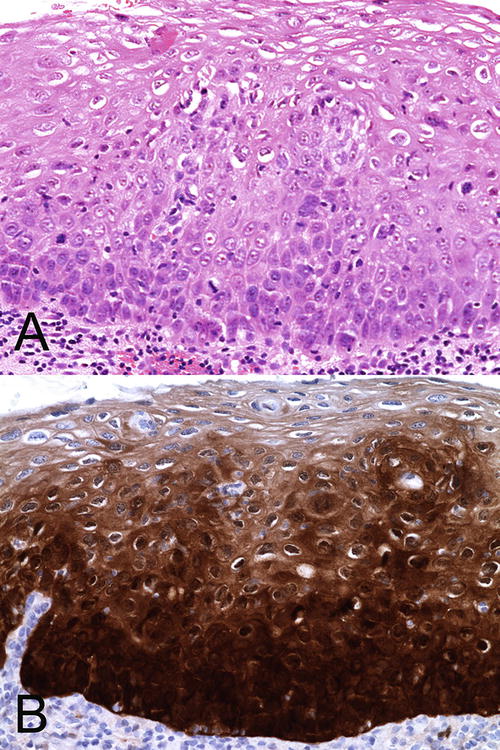

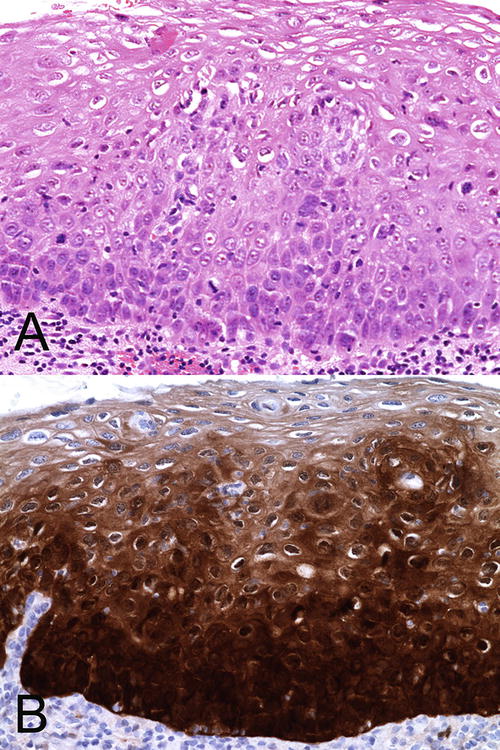

Fig. 10.9

(a) Recommended use of p16 immunostain to confirm a morphological impression of VaIN II (HSIL). H&E ×40. (b) There is almost full-thickness epithelial staining with p16. The cells are stained diffusely and intensely

Ki-67

The MIB1 proliferative index may be estimated by using the immunohistochemical stain ki-67. This is a nonhistone protein expressed in the cell nucleus in all phases of the cell cycle except for G0 and early G1 [71]. In normal, non-inflamed, nonneoplastic squamous or metaplastic epithelium, the staining is limited to the parabasal cells. In LSIL and HSIL, the staining extends to the intermediate squamous cells and all layers of the epithelium, respectively (Fig. 10.10) [69, 72, 76, 77]. It is a very sensitive but nonspecific marker as reactive inflammatory lesions may also result in similar staining patterns as SILs [69]. The concurrent use of p16 does not seem to improve the accuracy of identifying and grading SIL [72].

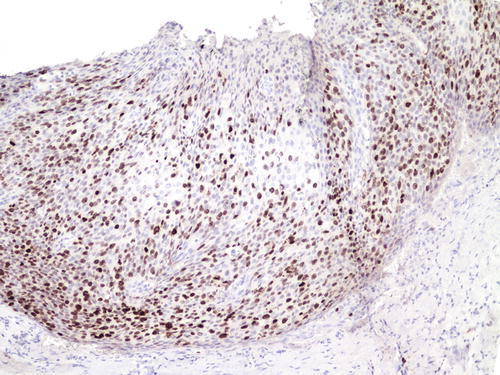

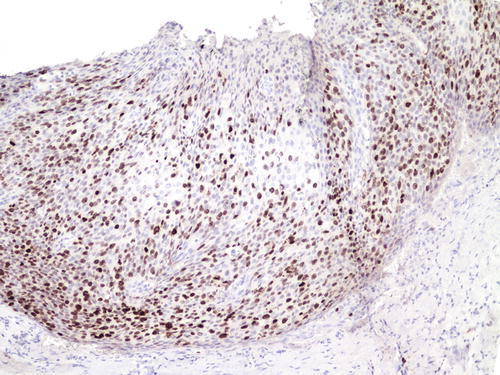

Fig. 10.10

The MIB1 proliferative index (ki-67) is elevated with positive staining in nuclei reaching the upper layers of the epithelium

ProEx C

ProEx C is an antibody that targets the expression of topoisomerase II-alpha and minichromosome maintenance protein-2, where these two genes are shown to be overexpressed in cervical cancers [71, 78]. The expression of ProEx C indicates an underlying aberrant S-phase induction [79]. In normal nonneoplastic epithelium, ProEx C staining is confined to the basal cells. In 90–92 % of HSIL, the staining extends to both the lower and upper half of the epithelium. Staining in LSIL is more variable, and metaplastic epithelium may also show suprabasal cell staining. Like p16, ProEx C is proposed to be useful in distinguishing between HSIL and reactive lesions but not between HSIL and LSIL [78, 79].

Differential Diagnoses

The lack of epithelial cell maturation in transitional cell metaplasia may potentially be confused with SIL. The cells in the former may have mild to moderate nuclear atypia and may have perinuclear halos. Unlike SIL, however, cell nuclei in transitional cell metaplasia are often spindle with tapered ends and have longitudinal nuclear grooves. The nuclei of the parabasal cells are usually oriented vertically to the basement membrane while those nearer to the surface are horizontal. Mitotic figures are usually rare [80]. As noted earlier, the vaginal mucosa is particularly thin and atrophic in postmenopausal women and is susceptible to trauma and erosion. Reactive atypia in these cases may be difficult to distinguish from true SILs. However, mitotic activity is uncommon in atrophy. Administration of topical estrogen cream in the vagina would induce epithelial maturation, and truly dysplastic lesions will then be apparent in cytology or biopsy. In those cases without coexisting active inflammation, the use of ki-67 and p16 immunostains may facilitate the differential diagnosis of SIL from reactive atypia, postirradiation atypia, atrophy, transitional cell metaplasia, and immature squamous metaplasia within adenosis [75, 77]. In nondysplastic conditions, the p16 stain is either negative or may show patchy staining, while the ki-67 index is usually low. Extramammary Paget’s disease is characterized by the presence of intraepithelial large cells with abundant cytoplasm and vesicular nuclei. They usually involve the basal epithelial layers but sometimes can be extensive, making it difficult to distinguish from SIL, particularly in small biopsies. Paget’s cells usually contain cytoplasmic mucin and are immunoreactive for CK7 and GCDFP-15.

Molecular Properties

The infected basal and parabasal epithelial cells initially remain morphologically normal because HPV gene expression is inhibited to a maintenance level only. Productive gene expression is tightly regulated until the cells have begun terminal squamous differentiation. At this juncture, the appearance of nuclear atypia such as enlargement and hyperchromasia is related to the rise in E6 and E7 viral proteins. In high-risk HPV genotypes E6 and E7, viral proteins cause cell cycle disruption. E6 binds to p53 protein and inhibits apoptosis, while E7 binds to pRb protein and activates the transcription factor E2F, thereby causing DNA replication [81–84]. These events cause keratinocytes to lose terminal differentiation, and histologically, the affected cells resume an immature appearance and manifest as HSIL. As a result of the suppression of the host innate and adaptive immune responses and for other unknown reasons, some high-risk HPVs have evolved the ability to become persistent for many years. The deregulation of E6 and E7 genes in persistent infection leads to an increase in cell proliferation of the basal/parabasal cells, i.e., those that are still capable of cell division, which is directly responsible for genomic instability, accumulation of genetic errors, and viral integration into the host genome [34, 85–88].

Infection caused by the low-risk HPV genotypes usually results in LSILs, which are clinically flat and inconspicuous lesions and will regress spontaneously with time. The production of viral DNA mainly occurs in cells that can no longer divide, i.e., intermediate squamous cells [89]. In low-risk HPV, the E6 and E7 viral proteins, respectively, do not bind p53 and pRb proteins with as high affinity as those in high-risk genotypes, and the precise mechanisms of their contribution to neoplastic transformation are unclear. Nonetheless, the role of wound healing response in causing the proliferation of infected basal/parabasal cells harboring the virus is thought to play an important part [90–92]. LSILs are DNA stable lesions , and the enlarged nuclei are either euploid or polypoid. The nuclear atypia is accompanied by cell maturation and acquisition of cytoplasm. Koilocytic change is related to an increase in cytokeratin binding protein E4 [93].

Patient Outcome

The natural history of vaginal SIL is less well studied. In general, LSIL that is associated with low-risk HPV infection usually resolves spontaneously around 2 years as the virus is cleared [36–38]. Some HSIL related to high-risk HPV is more likely to develop into persistent infection and subsequent progression into carcinoma. In several studies, 3–8 % of SIL progressed into squamous cell carcinoma in spite of treatment and close surveillance [15, 61, 94–96]. Local recurrence is more likely with larger lesions, inadequate excision, and involvement of margins [13]. Recurrence may also be related to the fact that these lesions tend to be multifocal and clinically invisible, and complete excision is difficult to achieve [19, 97]. The risk of recurrence is not related to the grade of VaIN (SIL) though VaIN III may recur at a much shorter interval from the time of its first treatment [16, 95]. Smoking may lead to recurrence and progression into carcinoma [98]. There are no proven histologic biomarkers that could predict which cases of SIL are more likely to progress to carcinomas. Nonetheless, follow-up with high-risk HPV molecular testing will identify patients with persistent infection who are more likely to have progressive disease [99–102].

Premalignant Glandular Lesions of the Vagina

Vaginal mucosa is normally devoid of glands and primary adenocarcinomas are rare. Adenocarcinoma in situ of the vagina has not been a well-defined entity, and criteria of diagnosis have not been established. Lesions considered as premalignant in this context have been described when they are found contiguous to the invasive tumors and usually show various degrees of epithelial dysplasia . These include adenosis, endometriosis, mesonephric remnants, urethral diverticulum, Skene’s gland, and endocervicosis [57, 103–112]. Some cases develop as a result of incomplete excision of cervical adenocarcinoma in situ [113].

Vaginal adenosis has been implicated as a precursor lesion to adenocarcinoma. The majority of clear cell carcinoma of the vagina described in the past was found in association with adenosis in the setting of in utero DES (Fig. 10.11) [51–53]. With discontinued usage of DES, the incidence of these tumors is decreasing. Apart from this association, vaginal adenosis may also arise de novo, secondary to tamoxifen, CO2 laser vaporization, topical 5-fluorouracil treatment for vaginal condyloma /SIL, and Stevens-Johnson syndrome [56, 114–117]. Grossly, vaginal adenosis is granular and red. Most are found involving the upper third. In those related to DES, there may be other coexisting congenital abnormalities such as transverse ridges of the vagina [54]. Microscopically, the adenosis consists of glands, either replacing the surface squamous epithelium or being found in the superficial vaginal stroma. The glands are lined by endocervical-type mucinous epithelium, but tuboendometrioid-type epithelium may also be found. Squamous metaplasia of these epithelia is common (Figs. 10.12, 10.13, and 10.14). As noted earlier, the squamocolumnar junctions in these may become the targets for HPV infection and hence develop into premalignant and malignant lesions [54–57]. Intestinal metaplasia is rare and seldom gives rise to an intestinal-type adenocarcinoma [105, 118, 119].

Fig. 10.11

Vaginal adenosis in a case associated with a coexisting clear cell carcinoma . A “premalignant” gland showing dysplasia and clear cell change (right lower). H&E ×20

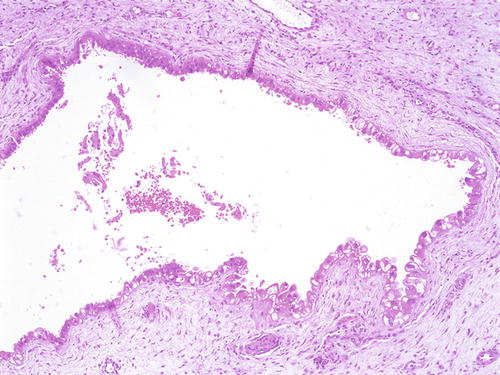

Fig. 10.12

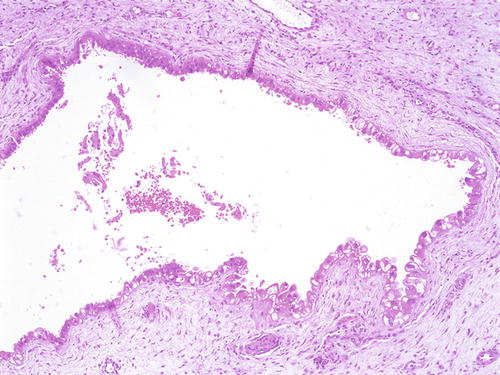

Vaginal adenosi s. The glandular epithelium is commonly found beneath the surface mucosa. H&E ×20

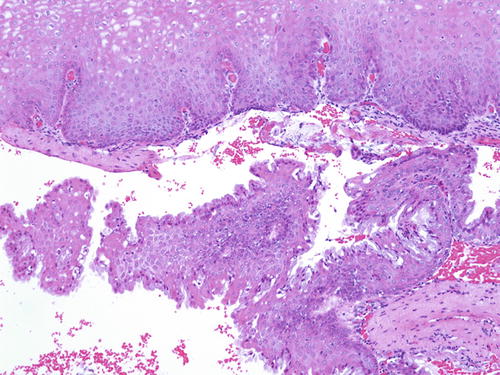

Fig. 10.13

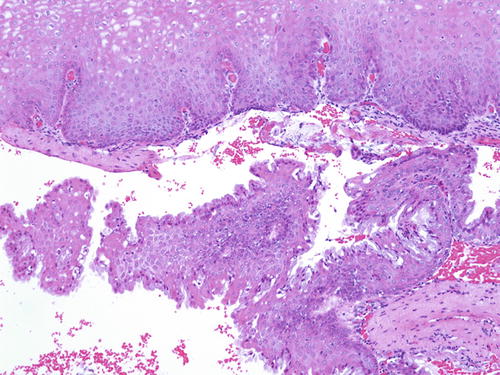

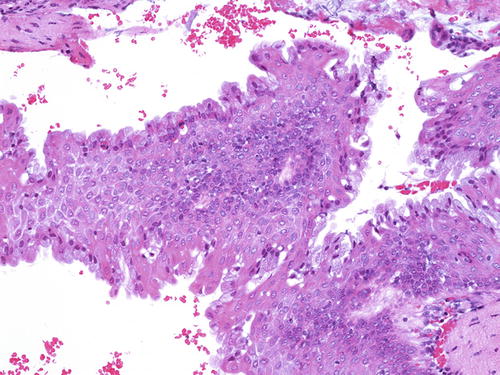

Vaginal adenos is. The mucinous epithelium often undergoes squamous metaplasia (left). H&E ×40

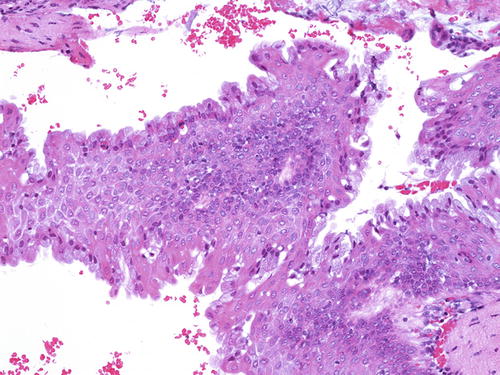

Fig. 10.14

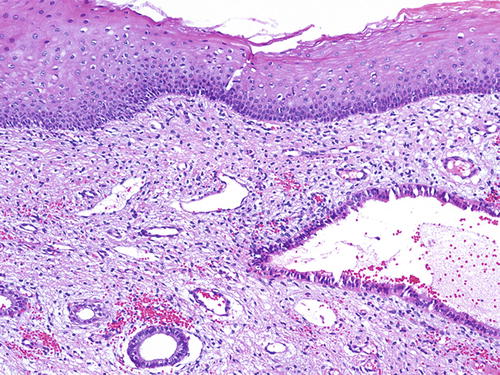

Vaginal adenos is. The glandular epithelium may be of ciliated tuboendometrioid type. H&E ×20

About two-thirds of primary endometrioid carcinoma of the vagina is secondary to a preexisting endometriosis. In these, the latter shows transition into the invasive tumor, supporting the view that this is indeed the premalignant lesion [57, 103]. Endometriosis of the vagina is rare. Some are secondary to trauma induced by previous hysterectomy, and these are usually of the superficial type. Others may be an extension of pelvic endometriosis involving pouch of Douglas or rectovaginal septum, and these are often found deep in the vaginal stroma. The etiologies for malignancy arising from endometriosis include unopposed estrogen and tamoxifen treatment [120–123]. Histologically, vaginal endometriosis is identical to those found elsewhere, but in cases in which there is an established adenocarcinoma, the glandular epithelium usually shows dysplasia resembling atypical hyperplasia of the endometrium.

References

1.

Cruveilhier. Varices des veines du ligament rond, simulant une hernie inguinale.—Anomalie remarquable dans la disposition gènéral du péritoine.—Cancer ulcéré de la paroi antérieure du vagin et du bas-fond de la vessie.—Col utérin, proéminent, etc. Bull Soc Anat Paris. 1827(2):199–205.

2.

Hummer WK, Mussey E, Decker DG, Dockerty MB. Carcinoma in situ of the vagina. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1970;108(7):1109–16.PubMed

3.

McCartney AJ. Surgery of intraepithelial neoplasia, CIN, VAIN, and VIN. Baillieres Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 1987;1(2):447–84.PubMed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree