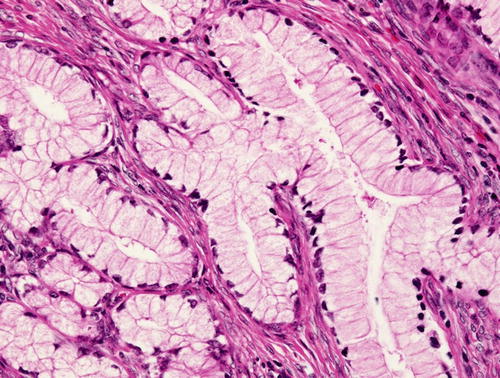

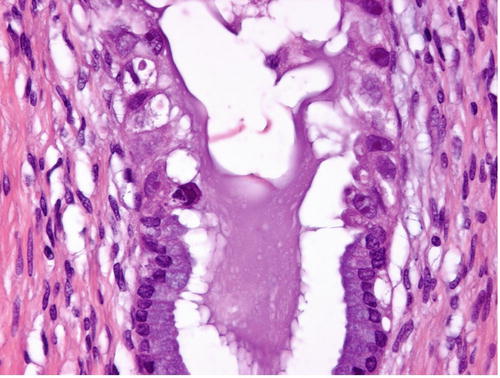

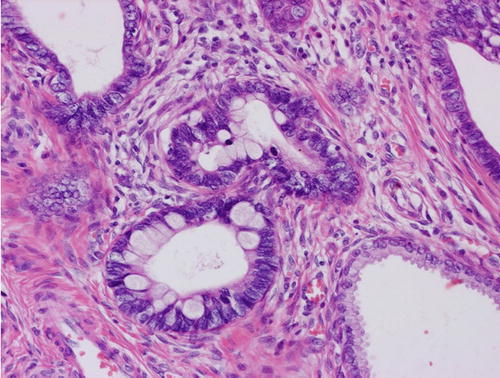

Fig. 12.1

Usual-type adenocarcinoma of the cervix, composed of tall columnar cells with significant nuclear enlargement, elongation, stratification, and hyperchromasia. The cytoplasm is rather dark, and intracytoplasmic vacuoles are absent or obscured (a). PAS-Alcian blue double staining showing the absence or paucity of intracytoplasmic mucin (b)

Table 12.1

World Health Organization classification of glandular lesions of the uterine cervix (4th ed., 2014) [1]

Glandular tumor and precursors |

Adenocarcinoma in situ |

Adenocarcinoma |

Endocervical adenocarcinoma, usual type |

Mucinous carcinoma, NOS |

Gastric type |

Intestinal type |

Signet-ring cell type |

Villoglandular carcinoma |

Endometrioid carcinoma |

Clear cell carcinoma |

Serous carcinoma |

Mesonephric carcinoma |

Adenocarcinoma admixed with neuroendocrine carcinoma |

Benign glandular tumors and tumor-like lesions |

Endocervical polyp |

Mullerian papilloma |

Nabothian cyst |

Tunnel clusters |

Microglandular hyperplasia |

Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia |

Diffuse laminar endocervical glandular hyperplasia |

Mesonephric remnants and hyperplasia |

Arias-Stella reaction |

EndocervicosisEndometriosis |

Endometriosis |

Tuboendometrioid metaplasia |

Ectopic prostate tissue |

Mucinous carcinoma is defined as a tumor composed of cells with abundant intracytoplasmic mucin and, in the previous version of the WHO classification (2003), included endocervical type, intestinal type, signet-ring cell type, minimal deviation type (MDA, “adenoma malignum ”) (Fig. 12.2), and villoglandular type [2]. In the mucinous category, endocervical type, defined as adenocarcinoma composed of cells resembling normal endocervical cells, was the most common, accounting for approximately 90 % of all cervical adenocarcinomas in the WHO 2003 scheme. However, in reality, the most common adenocarcinomas encountered by pathologists are very frequently mucin deficient or have only a tiny amount of intracytoplasmic mucin demonstrated by mucin staining (Fig. 12.1), and adenocarcinomas without any specific direction of differentiation or characteristic morphology, including serous, clear cell, endometrioid, or mesonephric carcinomas, have been designated as endocervical-type mucinous adenocarcinoma. This means that this subtype is a “waste basket” category and thus the term “usual type” has been proposed and incorporated into the revised WHO classification (2014) [1, 3]. In this context, combined with the observation that true mucinous carcinomas show aggressive behavior [4, 5], mucinous carcinoma was separated from the usual type to include gastric type (Fig. 12.3), intestinal type, and signet-ring cell type [1]. Gastric type mucinous carcinoma (GAS) is an emerging subtype of mucinous carcinoma , which shows aggressive clinical behavior and spectrum of morphological differentiation, encompassing MDA as its extremely well-differentiated variant [1, 6].

Fig. 12.2

Minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (“adenoma malignum”), which is true mucinous carcinoma , is characterized by well-formed glands composed of cells with abundant intracytoplasmic mucin and basally located nuclei with bland nuclear morphology

Fig. 12.3

Gastric type mucinous carcinoma, characterized by abundant clear or pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and distinct cell borders. Some cytologic features are shared by minimal deviation adenocarcinoma (MDA), but architectural abnormalities and distinct nuclear anaplasia are straightforward to indicate their malignant nature in contrast to MDA

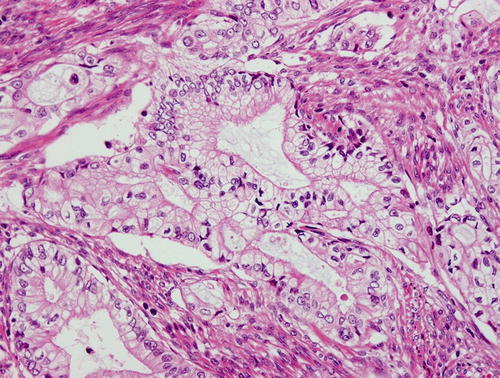

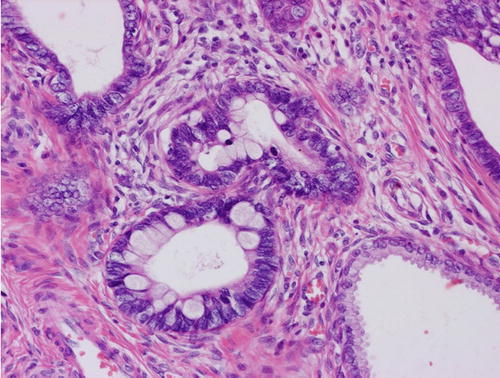

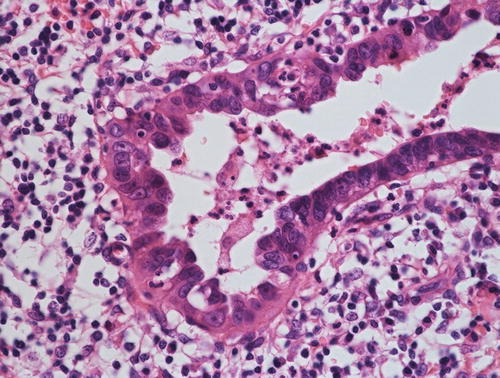

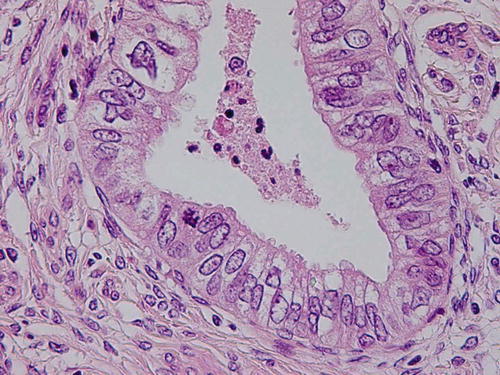

Fig. 12.4

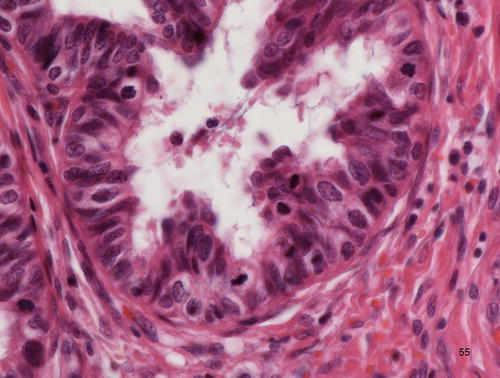

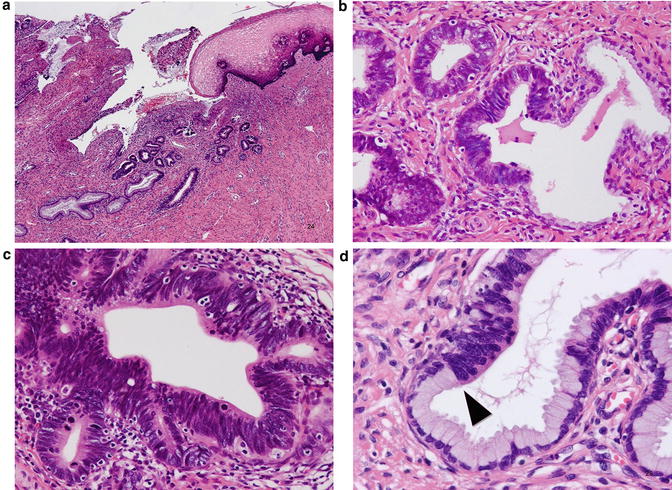

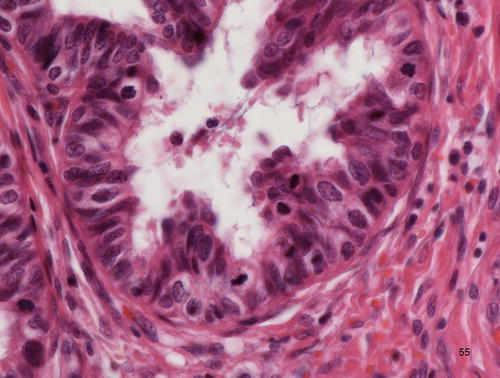

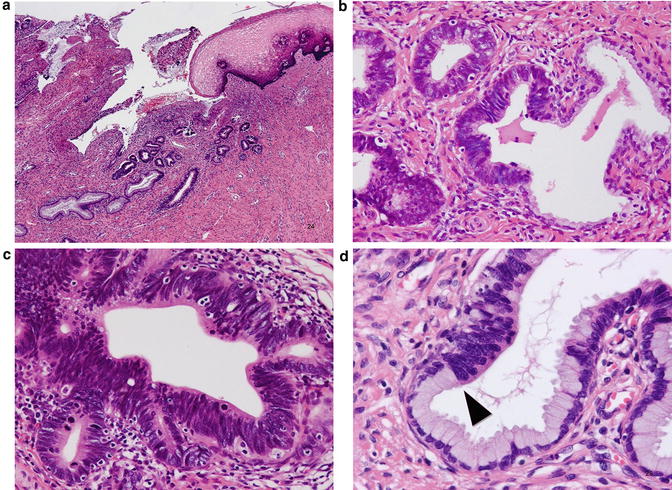

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), usual type. The lesion is typically found in the transformation zone where (a) preexisting endocervical glands are replaced by columnar cells with malignant-appearing cells (b). These tall columnar cells show moderate to marked nuclear enlargement, nuclear stratification, and heterogeneity in nuclear size and hyperchromasia, with occasional mitotic figures (c), and sometimes show a distinct border adjacent to preexisting endocervical epithelium (d), which is not a feature of reactive atypia

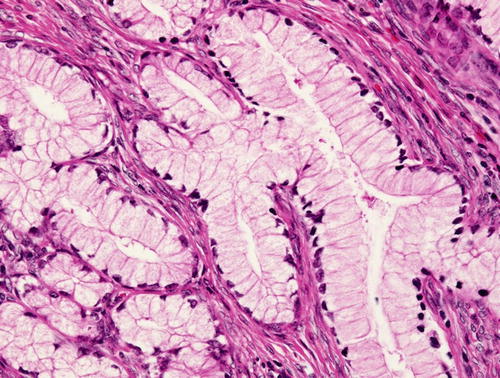

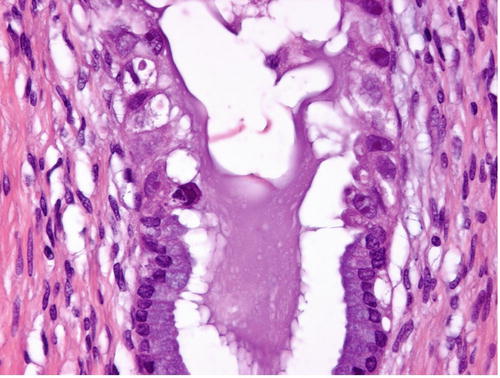

Fig. 12.5

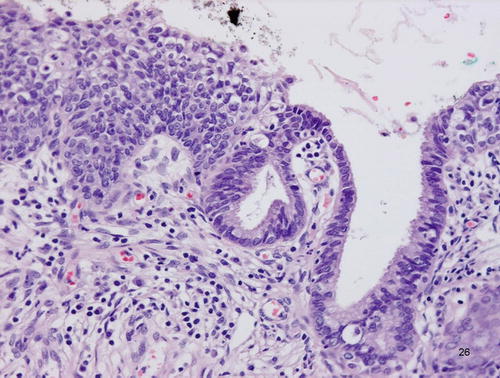

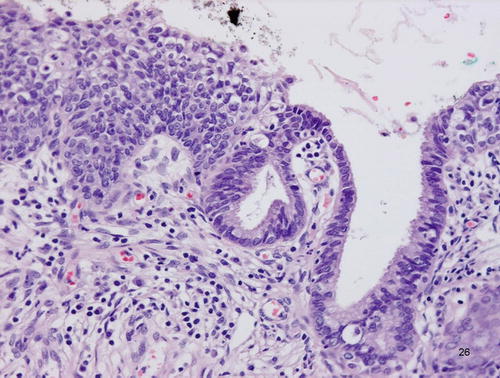

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) associated with high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesions (HSIL) (CIN 3) identified in the transformation zone, suggesting a common implication of high-risk HPV. This should be distinguished from adenosquamous carcinoma in situ or stratified mucin-producing intraepithelial lesion (SMILE)

Fig. 12.6

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), intestinal type , composed of a mixture of columnar cells and goblet cells

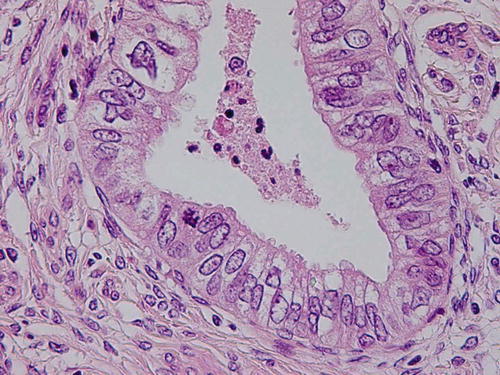

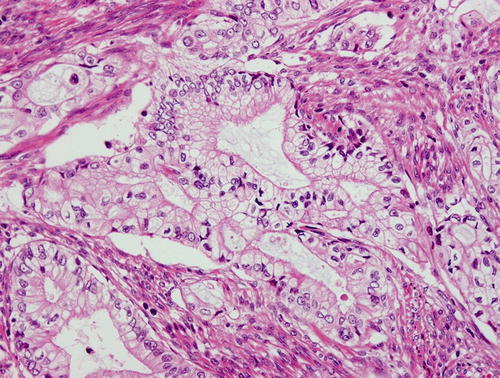

Fig. 12.7

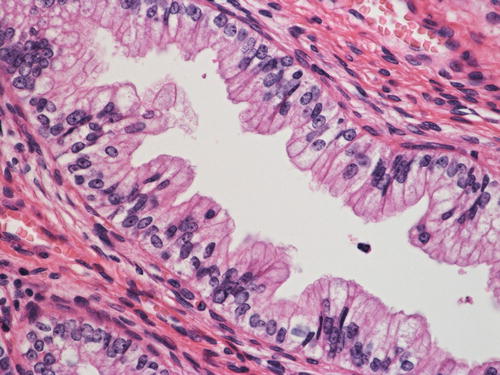

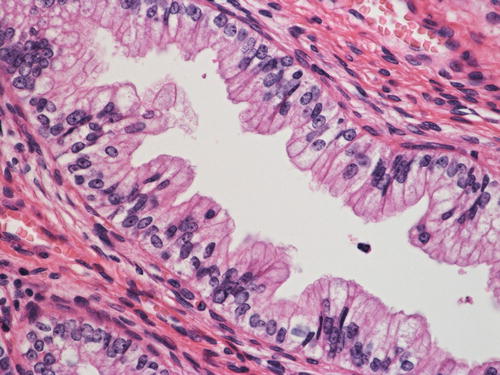

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), endometrioid type, characterized by mucin-deficient columnar cells with cilia. Nuclear morphology, including enlarged vesicular nuclei and nucleoli, nuclear stratification, and mitotic figures indicate the malignant nature of the lesion

The detection rate of high-risk HPV in adenocarcinoma cases varies from approximately 62 % to up to 97 % [7–11], reflecting a variety of factors including differences in patient population, age distribution, socioeconomic status, and geography. From the view of the implication of high-risk HPV, cervical adenocarcinomas can be divided into two categories (Table 12.2), and precancerous glandular lesions may be best discussed with regard to their relationship with high-risk HPV and differently for each morphologic subtype. The representative HPV-related tumor includes usual type and intestinal type carcinomas, whereas HPV-negative tumors include GAS, serous carcinoma, endometrioid carcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and mesonephric carcinoma with some exceptions [9–13]. There are some studies demonstrating the detection of HPV in cases of serous and endometrioid carcinomas [9–14]; however, this may be mostly a consequence of different criteria employed for the individual studies. Usual type endocervical adenocarcinomas occasionally show micropapillary growth patterns, imparting a close resemblance to serous carcinoma. In other words, a subset of serous carcinoma of the cervix is a morphologic variation or a consequence of high-grade transformation of usual type, which are HPV-related. On the other hand, a significant number of usual types might have been regarded as endometrioid carcinoma because of a paucity of intracytoplasmic mucin, resulting in its higher incidence in some studies (up to 30 %) [3, 15]. Using strict criteria, endometrioid carcinoma is a rare neoplasm, accounting for less than 10 % of all cervical adenocarcinomas [3], and most tumors diagnosed as such are considered HPV-negative.

Table 12.2

Division of cervical adenocarcinoma based on HPV implication

High-risk HPV-positive adenocarcinoma | High-risk HPV-negative adenocarcinoma |

|---|---|

• Usual type (previously called endocervical type mucinous adenocarcinoma) • Intestinal type mucinous carcinoma • Serous carcinomaa • Endometrioid carcinomaa | • Gastric type mucinous carcinoma (including minimal deviation adenocarcinoma) • Mesonephric carcinoma • Serous carcinoma • Endometrioid carcinoma |

Clear cell carcinoma shows features similar to ovarian and endometrial clear cell carcinoma . Moreover, it is well known to be associated with in utero exposure to diethylstilbestrol (DES), a synthesized estrogen [16], and recent studies have shown that it is mostly not associated with HPV infection [12, 14, 17]. Notably, Ueno et al. demonstrated an increased EGFR or HER2 expression or activation of AKT or mTOR in all clear cell carcinomas in their series, which suggests that tyrosine kinase inhibitors targeting the AKT-mTOR pathway are potential treatment regimens for this particular tumor [17].

Mesonephric carcinoma , characterized by columnar or cuboidal neoplastic cells arranged in a glandular pattern containing diastase-resistant Periodic acid-Schiff (PAS)-positive proteinaceous eosinophilic secretions, with occasional papillary or reticular patterns, is considered to be derived from mesonephric remnant and is typically located deep in the cervix away from the transformation zone, which is the preferential site of HPV-related adenocarcinoma development.

The concept of GAS has been proposed based on the observation of clinicopathologic features of MDA . MDA was demonstrated to show a gastrointestinal phenotype by immunohistochemistry using HIK1083 and anti-MUC6 antibodies, both of which recognize pyloric gland mucin of the stomach [18]. Although their phenotypic characteristics were considered to be specific for MDA, one of the authors (YM) revealed that a subset of so-called endocervical-type mucinous adenocarcinomas can be positive for these two markers [19]. Because this tumor shares some characteristics, including the morphology [6] and absence of HPV detection [12, 14, 20], with MDA (although it does not match completely with prototypical MDA because of less differentiation), these tumors were separated as a distinct entity (GAS) [1, 6]. Morphologically, GAS is characterized by abundant clear or pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and distinct cell borders, and it shows aggressive clinical behavior [6].

General Aspects of Cervical Adenocarcinoma Precursors

Based on the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program data, Wang et al. demonstrated that adenocarcinoma accounts for approximately 20 % of all cervical carcinomas, but the cervical intraepithelial neoplasia 3 (CIN 3 ) to adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS) ratio is 34, suggesting a low incidence of AIS as a precursor of invasive carcinoma compared with CIN 3 [21]. In addition, they revealed that AIS to adenocarcinoma and CIN 3 to squamous cell carcinoma (SCC) ratios are 0.8 and 6.69, respectively [21]. The low incidence of AIS and higher incidence of its invasive counterpart may be explained by four possibilities:

Regarding common AIS types, in a series of early invasive adenocarcinomas, AIS was identified in up to 85 % of cases [22], and the time-to-progression to its invasive counterpart, ranging from 2 to 8 years, appears not significantly different from high-grade squamous intraepithelial lesion (HSIL) (CIN 2/3) [22–24], and therefore the latter two might be main sources of the low detection rate of AIS [25]. In the literature, however, there are cases of small invasive carcinoma without AIS, suggesting a rapid progression [22]. Information on the natural history of AIS is still limited, and thus, in cases of uncommon subtype of AIS, a variety and combination of factors may be considered.

1.

Cervical adenocarcinomas are not derived from AIS.

2.

AIS rapidly progresses to invasive carcinoma with a very short interval, escaping the screening program.

3.

AIS cannot be detected by conventional sampling because of its topographic characteristics, i.e., the location beneath the surface epithelium in the cervical canal.

4.

Limitations of the current diagnostic criteria for interpreting Pap smears, particularly in cases of AIS with minimal cytologic atypia.

AIS and Its Variations

AIS is defined as an intraepithelial lesion containing malignant-appearing glandular epithelium that carries a significant risk of developing into invasive adenocarcinoma if not treated [1]. By definition, desmoplastic stromal reaction indicating destructive invasion is absent in cases of AIS, although intraglandular tufting or cribriform growth may be seen. In the literature, Friedell and McKay first described AIS in 1953 [26], and thereafter the lesion has been widely accepted as a precancerous lesion. The rationale indicating the precancerous nature of AIS includes:

Clinically, AIS is commonly asymptomatic and is mostly detected by screening. Patient age varies from 18 to 75 with a mean age of 35 in one large study [27]. The incidence varies, e.g., 1 in 25,000–475,000 women, depending on race, geography, and socioeconomic status [36, 37].

In addition to the common usual type (endocervical type ) as described by Friedell et al. (Figs. 12.4 and 12.5) [26, 38], there are a variety of morphologic subtypes of AIS, including intestinal type [38] (Fig. 12.6), endometrioid type (Fig. 12.7) [38], clear cell type (Fig. 12.8) [39], serous type (Fig. 12.9), and tubal or ciliated type (Fig. 12.10) [40]. Gastric type of AIS (Fig. 12.11) has also been described [19]. The subclassification of AIS does not appear to have any impact on patient management, but pathologists are encouraged to be aware of the morphologic spectrum of AIS of the uterine cervix to avoid misinterpretation and in order to understand the histogenesis of cervical adenocarcinoma.

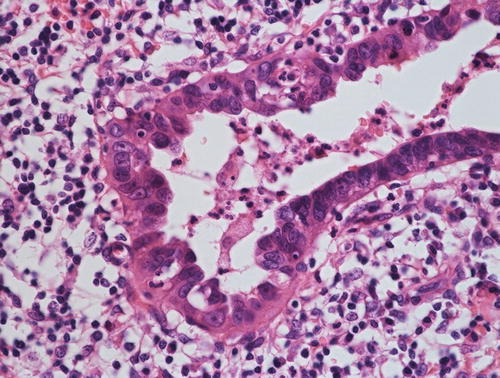

Fig. 12.8

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), clear cell type. Atypical cells with abundant clear cytoplasm, showing hobnail appearance, lining the preexisting endocervical glands

Fig. 12.9

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), serous type. Replacement of preexisting normal endocervical cells replaced by cells with significant nuclear pleomorphism, showing heterogeneity in nuclear size and shape

Fig. 12.10

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), tubal type. Atypical columnar cells with cilia and intermingling of peg cell-like cells

Fig. 12.11

Adenocarcinoma in situ (AIS), gastric type, characterized by lining cells with abundant clear or pale eosinophilic cells with distinct cell borders; the nuclear morphology is rather unremarkable and thus is a diagnostic concern

Microscopically, the usual type of AIS is typically located in the transformation zone with some exceptions. On low power view, it can be recognized by deeply stained columnar epithelium (Fig. 12.4a, b) because of moderate to marked nuclear enlargement, overlapping, and hyperchromatism (Fig. 12.4c), in contrast to the basally located small nuclei of normal glandular epithelium. Atypical columnar cells replace preexisting mucus-secreting columnar cells, and the contour of the endocervical glands is preserved. The atypical cells commonly extend from the superficial to the deeper portion of the glands and frequently show a clear front with preexisting nonneoplastic glandular epithelium (Fig. 12.4d). It should be kept in mind that AIS involving nonspecific endocervical glandular hyperplasia may show gland crowding, making early invasion a diagnostic concern. Therefore, the distribution and architecture of the background nonneoplastic glands should be considered, as well as the architectural complexity of atypical glands, desmoplastic stromal reaction, and inflammatory reaction. Although there is heterogeneity with respect to nuclear size and shape, the nucleolus is usually absent or small, and vesicular nuclei with conspicuous nucleoli and significant nuclear pleomorphism are rather indicative of invasive adenocarcinoma. The amount of intracytoplasmic mucin is also lower. Mitotic figures and apoptosis and the existence of the front formation are diagnostically important [41], and, in the absence of these features, pathologists should be careful and consider AIS mimics including tubal metaplasia as differential diagnoses. The characteristic front formation indicates that AIS arises de novo without a precursor lesion, which is biologically and morphologically intermediate between normal epithelium and AIS [42]. Approximately two-thirds of cases are incidentally found on biopsy or conization for HSIL (Fig. 12.5) [38].

The intestinal type AIS is characterized by an admixture of goblet cells (Fig. 12.6). Neuroendocrine cells that show immunoreactivity for chromogranin can be also identified, but Paneth-like cells are rarely seen. McCluggage et al. demonstrated CDX2 positivity in cases of intestinal type AIS, indicating the true enteric differentiation of this particular lesion. Nuclear abnormalities may be minimal, and therefore pathologists are encouraged to perform a diligent search when encountering a lesion interpreted as intestinal metaplasia since it may represent a neoplastic condition [43].

Endo metrioid type AIS is composed of cells with almost no intracytoplasmic mucin (Fig. 12.7). This type, like the tubal type, may be associated with tuboendometrioid metaplasia [40], and thus the associated invasive adenocarcinoma is located in the higher portion of t he endocervical canal away from the transformation zone [22].

Interestingly, Jaworski et al. examined AIS subtypes, and in their series, they found that endometrioid type more frequently coexists with usual type and/or intestinal type and is only occasionally found alone and that intestinal type is always in association with usual type and/or endometrioid type [38]. These results suggest possibilities that intestinal type AIS is derived from usual-type AIS and that the endometrioid type may be classified into two groups: HPV-negative de novo type and HPV-positive usual type-related; the latter might represent mucin-deficient usual type AIS.

Clear cell type AIS shows atypical cells with abundant clear or pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and hobnail appearance (Fig. 12.8). It imparts a close resemblance to the Arias-Stella reaction and thus can be a diagnostic pitfall, although, from a practical point of view, it may be better to think of a benign diagnosis in a pregnant woman.

Gastric type AIS is characterized by abundant clear or pale eosinophilic cytoplasm and enlarged vesicular nuclei with conspicuous nucleoli (Fig. 12.11). Lobular endocervical glandular hyperplasia (LEGH) with intraepithelial carcinoma (atypical LEGH) is distinguished from this condition by its characteristic lobular architecture, but both of these conditions might be GAS precursors [19]. It should be kept in mind that the nuclear abnormalities in cases of gastric type AIS may be very unremarkable and thus can be overlooked without familiarity of its cytologic features. Immunohistochemically, this type is positive for HIK1083 and MUC6, which are representative gastric markers [19]. Occasionally, it can be positive for p16INK4a [19], suggesting an implication of high-risk HPV, but this remains undetermined.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree