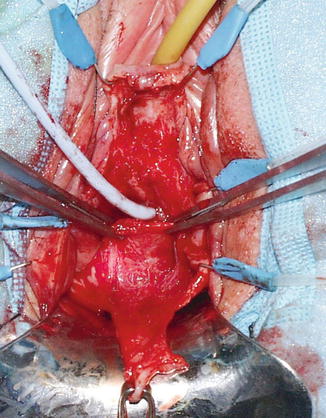

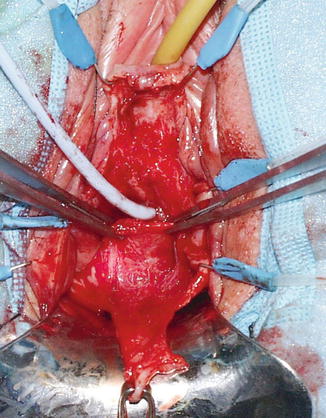

Fig. 10.1

The peritoneum is located near a post hysterectomy vesicovaginal fistula (Copyright © Shlomo Raz, MD)

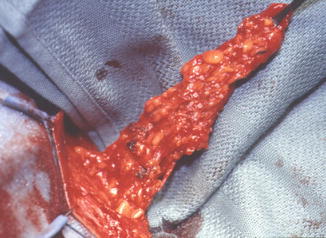

Fig. 10.2

Martius flap based on its inferior pedicle, posterior labial branches of the internal pudendal artery (Copyright © Shlomo Raz, MD)

Rotational labial and inner thigh rotational flaps are selected for specific conditions: large vaginal defects, difficult vaginal access requiring a relaxing incision, and subsequent need for vaginal coverage, large, recurrent, or radiation-induced fistula. When there is a large vaginal defect these flaps can provide fibroadipose tissue and skin coverage with a well vascularized blood supply. Full thickness rotational labial flaps, for anterior vaginal wall, or gluteal flaps, for posterior or proximal vaginal wall, are chosen depending on the location of where the flap is needed. A full thickness rotational labial flap is the same fatty tissue of a martius flap with its overlying skin that is rotated to cover an anterior vaginal defect. The fistula is first repaired and then a U-shaped incision is made lateral to the labia majora with the apex located at the posterior fourchette. The flaps’ blood supply is from the superior pedicle which is based on the external pudendal artery. This flap is dissected free from the fascia of the pubic bone so that it can be rotated medially to achieve repair. In a small series there has been a successful report of this technique [17].

A full thickness gluteal inner thigh rotational flap is reserved for complex refractory fistula. With the patient in the lithotomy position, a mediolateral episiotomy is made at 5 O’ clock extending from the introitus to the vaginal apex. Dissection is continued into the para-rectal space. A 4 × 12 cm inner thigh flap is prepared by making an inverted U-incision lateral to the labia major extending from the ischial tuberosity inferiorly, and to the pubic rami superiorly. This incision preserves the blood supply from the internal pudendal artery and innervation from the labial branches of the internal pudendal nerve and perineal branches of the posterior cutaneous nerve of the thigh. Dissection is carried to the level of the fascia. The episiotomy is extended to the infero-medial aspect of the flap to allow complete mobility. This creates a lateral gluteal rotational inner thigh flap and a medial labial flap. The labial and gluteal rotational inner thigh flaps are crossed; the inner thigh flap medially and the labia flap laterally. The inner thigh flap is transferred and sutured to the vaginal defect. This is a functional full thickness flap that provides good sensation and adequate vaginal width and depth. A variation of the full thickness inner thigh flap is the Singapore island flap [18]. The dissection of the flap is similar except that the episiotomy is avoided and the flap is tunneled to the defect. The epithelium of the flap is removed except for the area that is covering the fistula. This flap is used in complex fistula repair and may be preferred to the full thickness rotational inner thigh flap when there is already adequate vaginal access.

There are several reports of gracilis myocutaneous flap for radiation-induced fistula in which it is used for vaginal reconstruction [19, 20]. We seldom find it necessary to perform this technique because the rotational gluteal flap can duplicate many of the same functions of this gracilis graft without the associated morbidity and cosmetic defects.

The most described interposition is the omental flap which has increased success rates for abdominal repair in retrospective studies [16, 21]. The omentum is based on the right or left branch of gastroepiploic artery, although typically it is based on the right which is usually larger and more caudal. In cases of bowel resection the mesentery can be preserved and serve as a useful interposition which has similar properties as the omentum with a well vascularized blood supply and lymphatic drainage to decrease inflammation and promote healing. Other tissue interposition flaps that have been reported are bladder flaps [22–26].

Selection of closure and reconstruction of the urethra after UVF requires expertise and experience due to its complexity. Urethral reconstruction centers on different techniques, primarily urethral closure, vaginal and bladder flap advancement which includes pedicle flap (labia minora and anterior or posterior bladder), and use of grafts [27]. Surgical planning of the urethra reconstruction technique may influence vaginal incision location. In a complex fistula resulting in damage of nearly the entire urethra that can extend potentially to the bladder neck, a urethral reconstruction using vaginal or bladder flap construction with interposition of tissue would be preferred to a primary closure. It would be advised to place ureteral stents as the fistula may distort the anatomy and ureteral injury may be avoided during repair.

Evaluation

History and Physical Examination

Women with VVF and UVF most often present with constant urinary incontinence shortly after a pelvic surgery. The presenting symptoms may be recurrent urinary tract infections with chronic perineal changes exhibited by poor healing and irritated skin. Questioning the degree of difference voided and the amount leaked may give clues to the size and location of the VVF. Timing of the onset of leakage and whether there is stress incontinence or urge incontinence with overactive bladder symptoms before the VVF is important to consider in selecting treatment options and patient counseling. A patient with a UVF in the distal third of the urethra may remain continent and asymptomatic or they will commonly describe a splayed urinary stream. They may additionally complain of urinary leakage after vaginal voiding. When the fistula is in the mid-urethra and part of the external sphincter, the patient may have positional intermittent leakage of urine. Patients may have constant, large amounts of urine leaking indicating there is a large fistula that is located proximal to the mid-urethra in the proximal urethra or bladder neck. Gathering information to determine the etiology and prior surgical attempts to repair the fistula can affect the treatment plan.

On physical examination, there should be careful inspection of the fistula size, number, location, and quality of the surrounding tissue. The location of a VVF after hysterectomy is usually a single fistula at the vaginal cuff, although it may present as a complex VVF with multiple fistulas. Evidence of the fistula site is found with surrounding inflammation with granulation and tissue defect. Adequate vaginal access and the degree of mobility of the tissue surrounding the fistula is revealed by the amount of vaginal prolapse. Nulliparous patients or with a history of radiation may be challenging due to a lack of vaginal access and mobility because of narrow vaginal width. On exam, the integrity of the vaginal mucosa, urethral mobility, and assessment of stress incontinence with provocative maneuvers should be performed.

It is important to differentiate the origin of the vaginal drainage and not to make any assumptions as the fluid may be from the fallopian tube, vaginal secretions, peritoneum, lymph, or urine. The differential diagnosis of VVF is UVF, ureterovaginal, uterovaginal, ectopic ureter, or vaginal infection. It is important to differentiate the origin of vaginal drainage and not to make any assumptions as the fluid may be from other pelvic sources [3].

Patients with RVF have presenting clinical symptoms that include gas, stool, and purulent vaginal discharge. The physician should be aware that colonic or enteric fistula may present with similar symptoms as a RVF. The history should focus on causes of the fistula which is most commonly obstetric trauma, but also includes pelvic surgery, malignancy, history of radiation, pelvic abscess, and inflammatory bowel diseases. Occasionally, small or intersphincteric rectal vaginal fistula may be asymptomatic. Vaginal and bimanual exam should be performed taking note of the location, number, tissue quality, and size of the fistula. On exam, the fistula is normally clearly visualized and instilling dye into the rectum may be of assistance. The location of the fistula is important in deciding the operative approach and is classified into high and low in relation to the anal sphincter. High fistula may need to be approached abdominally and low fistula transvaginally. Occasionally examination under anesthesia is indicated for a more thorough evaluation. During physical examination anal sphincter tone should be evaluated as this may need concomitant repair.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of a urinary or rectovaginal fistula can most often be made upon a vaginal examination. A urethral catheter with retrograde filling of the bladder or rectum with dye may demonstrate the fistula on exam. A urinary fistula can be confirmed after administering phenazopyridine once it is excreted in the urine. By placing gauze or a tampon in the vagina, the gauze should turn orange in color in the presence of a fistula. A double dye tampon test can further delineate the origin and location of the fistula by giving the patient phenazopyridine followed by retrograde instillation of dye, methylene blue or indigo carmine, into the bladder through a catheter. A ureterovaginal fistula should be orange in the proximal part of the packing while a VVF or UVF should be blue in the mid or distal packing. A negative tampon test does not rule out a fistula and clinical suspicion is many times required to make the diagnosis.

There are varying opinions and no consensus on the imaging required in the evaluation of a VVF or UVF. Many patients have a complex history with postoperative complications and there are medico-legal implications that should be considered [28]. Our practice is to completely evaluate the patient to attempt to address all problems at the initial repair. A voiding cystogram during filling may demonstrate the fistula; however, the intradetrusor pressure may need to be increased during voiding to visualize small fistulas with the patient positioned in the lateral and oblique position. The lateral views may best demonstrate the fistula when it has a direct connection between the bladder and vaginal or when the connection is indirect and enters a collection/sinus tract before draining into the vagina. The VCUG can identify additional findings of a UVF which can be found concomitantly with VVF, the degree of vaginal prolapse, and stress incontinence [29]. Demonstration of preoperative stress incontinence may change the treatment plan by the addition of an anti-incontinence procedure or it may alter patient expectations, of postoperative leakage.

Upper tract evaluation to assess for abnormal findings of hydronephrosis or urinary extravasation from obstruction or fistula with CT urogram should be performed, although there are no formal recommendations to guide the surgeon. There is a 12 % upper tract injury with VVF [30]. Should there be further questions regarding ureteric involvement, a retrograde pyelogram would be justified as it is the most sensitive in detection of upper tract injury, although a CT urogram with reconstructions may be adequate in our experience [31]. Urine cytology is recommended for those with a history of malignancy or pelvic radiation.

It is our routine practice to perform a cystoscopy to evaluate for a urethral fistula and consider it mandatory when there is a history of hematuria or radiation. Urethroscopy should be performed with a short beaked rigid cystoscope (urethroscope or hysteroscope) or flexible cystoscope to allow full visualization of the urethra; the light and the irrigant are at the same level allowing direct vision and expansion of the urethral wall. A 30 and 70° optic lens allows identification of bladder abnormalities while a 0 or 15° lens is better for visualization of urethral foreign bodies or lesions. The fistula size and location in relation to the bladder neck, trigone, and ureteric orifice are determined on cystoscopy. If the fistula involves the bladder neck, it should be discussed with the patient as it may affect continence after repair. Findings on a cystoscopy can determine if ureteral stents are necessary and if a combined vaginal and abdominal approach are appropriate when there is ureteric involvement.

It is important to document preoperative sexual function and discuss potential postoperative complications. Vaginal stenosis is a potential complication that can be corrected with a subsequent vaginoplasty in most cases. Vaginal shortening may result when a martius flap has insufficient length for a proximal fistula or as a result of Latzko partial colpocleisis. The peritoneal flap is better situated for proximal fistula repair to prevent vaginal shortening.

Further radiologic evaluation with a CT of the abdomen and pelvis should be performed in cases of prior malignancy or in patients without other risk factors for RVF. Gastrografin enema may identify the location of the rectovaginal fistula. Proctosigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy may establish the diagnosis and evaluate for malignancy, especially in the case of radiation-induced fistula where about a third are malignant [32]. If there is any concern for malignancy, the fistula should be biopsied.

Anal sphincter tone should be evaluated preoperatively with physical examination. Nearly 50 % of patients have fecal incontinence which should be discussed and potentially treated simultaneously with fistula repair [33]. Our practice is to routinely obtain an endoanal ultrasound when the cause of the fistula is from trauma after vaginal delivery. Endoanal ultrasound and anal manometry testing can provide valuable information regarding sphincteric function and defects preoperatively.

Vesicovaginal Fistula

Background

Vesicovaginal fistula is an abnormal extra-anatomic connection between the bladder and vagina. Women with VVF suffer enormous amounts of physical, social, and psychological limitations. It is uncommon in western countries, although it remains a widespread problem in undeveloped countries due to obstructed labor [34]. In developed countries, VVF is most often a complication of pelvic surgery (hysterectomy) which we will direct the majority of our attention. VVF may associate with UVF and/or RVF [9, 35]. VVF usually presents with constant urinary incontinence that is distressing and may be intensified as a result of a surgical complication.

Etiology

VVF in the USA and developed countries are the result of gynecologic pelvic surgery in over 80 % of cases, with the remaining causes being comprised from radiation, malignancy, trauma, and obstetric instrumentation during childbirth [29]. Hysterectomy accounts for 91 % of the gynecologic pelvic surgeries that resulted in VVF [9]. A total of 600,000 hysterectomies are performed annually in the USA and nearly a third of women have hysterectomies for benign disease [36–38]. The reported incidence of fistula after hysterectomy for benign disease is reported to be 0.1 to 0.4 %. The risk of fistula increases about tenfold to 1–4 % after radical hysterectomy [39]. The majority of hysterectomies in the USA are performed abdominally with a Cochrane review reporting the risk of fistula formation is similar regardless of the approach, although there is increased risk of injury of urinary tract with laparoscopic hysterectomy [40, 41]. A national database registry study in Sweden found that abdominal and laparoscopic surgery had the highest fistula rate [39]. Fistula formation after hysterectomy is thought to be the result of unrecognized injury to the urinary tract at the time of surgery. The injury may be directly to the bladder or from inadvertently placed sutures that result in tissue necrosis. These injuries result in a urinoma that accumulates and drains through the vaginal cuff [42]. Preoperative risk factors for fistula formation after hysterectomy for benign and malignant disease are diabetes, smoking, history of c-section, endometriosis, pelvic inflammatory disease, and radiation [43–45]. Intraoperative findings of pelvic adhesions, bladder injury, extensive surgery, and higher stage cancer have higher risk of fistula [43–46]. Performing a subtotal hysterectomy with preservation of the cervix decreased the fistula rate which may be the result of a less extensive surgery [42]. Attention to avoiding injury to the urinary tract and performing a cystoscopy during difficult dissections where bladder injury is suspected may prevent a fistula [28]. It may be helpful to retrograde fill the bladder with dye or saline in these select cases to detect injury. Observation of the urine draining from the foley during hysterectomy should be clear and if there is question further investigation is indicated.

Pelvic surgery with mesh-augmented repair is another cause of fistula. There are reports from transvaginal mesh causing VVF at low rates 0.29 % [47]. A mid-urethral sling may inadvertently injure the bladder and cause a VVF [48]. This reinforces the importance of a cystoscopy at the time of sling placement to prevent urinary fistula. As the number of transvaginal mesh surgeries has been increasing, there may have been a rise in the number of urinary fistula from mesh complications [49]. Whether this trend may reverse as a result of decreased transvaginal mesh-augmented repairs due to the FDA safety communication in July 2011 regarding complications related to transvaginal mesh for POP remains to be seen.

Radiation-induced fistula represents a minor portion of VVF. The mechanism of injury is from obliterative arteritis resulting in ischemia which also produces inflammation of encompassing tissue [50]. Presentation of radiation fistula can occur acutely or be delayed for several years [3, 29]. Suspicion of recurrent cancer or secondary malignancy must be considered with a history of radiation fistula.

Treatment

Conservative Treatment

The goal of surgical repair is to have resolution of the fistula with the least morbidity. In select circumstances it is reasonable to attempt a trial of catheter for about 4 weeks [51]. There are reports of spontaneous resolution of fistulas that are simple and small with the overriding principle that there should be no delay in definitive repair [52–54]. Consideration of endoscopic treatment with fulguration and fibrin glue has been successfully reported in small case series when fistulas are less than 3.5 mm in size [55, 56]. This is a reasonable approach when patients meet these defined criteria; however, few patients are candidates for these conservative or minimally invasive procedures and require surgical repair. Patients with a history of fistulas that are complex, large, or radiation induced should proceed with definitive repair as minimally invasive treatment is futile.

Transvaginal Repair

Prior to surgery a detailed physical examination, urine analysis with culture if indicated, cystoscopy, and VCUG are performed with CT urogram with 3D reconstruction of the ureters in selected cases. We describe our basic technique and adjuvant procedures performed in complex cases. With the patient in lithotomy position, surgical repair begins with vaginal exposure with a ring retractor and vaginal speculum. The key to performing this repair is identification of the fistula tract. A cystoscopy is performed to identify the fistula and a wire is placed through it. Bilateral stent placement is done when the fistula is near the ureteric orifices. A 16–18 Fr catheter is inserted into the bladder. The vaginal cuff is grasped with Allis clamps or with stay sutures to expose the fistulous tract which is dilated with sounds over the guide wire to allow the passage of a 8–10 Fr catheter. The catheter is important in the exposure and retraction of the bladder during the repair. A circumferential incision is made less than 1 cm from the fistula track. An inverted U-incision is made on the anterior vaginal wall and it is mobilized 3–4 cm to create the anterior vaginal flap (Fig. 10.3). A posterior vaginal wall flap is created from the cuff to expose the prerectal fascia, the vesico-rectal space, and the posterior cul de sac where the peritoneal flap can be retrieved.

Fig. 10.3

Anterior vaginal flap that has been mobilized (Copyright © Shlomo Raz, MD)

The fistula tract is isolated and closed with 2-0 or 3-0 delay absorbable interrupted sutures. Care is taken to incorporate the entire fistulous tract and the bladder wall. At the end of the closure, diluted indigo-carmine tests the integrity of the repair. We omit excision of tract unless there is concern of malignancy or extensive necrotic tissue. The fistula tract is not routinely excised because it provides excellent anchoring tissue for closure, avoids creating a larger defect to repair that may prevent the need for ureteric reimplant, and prevents bleeding from the fistula tract edges that can become devitalized from electrocautery during control of bleeding [3, 57]. The bladder is filled with indigo carmine once the fistula tract is closed to ensure there is no extravasation. A second layer of sutures 1 cm from the fistula and imbricated over the tract with 2-0 or 3-0 delay absorbable interrupted suture for the second layer of closure. A double layer of peritoneal flap is dissected from the vesico-rectal space in the cul de sac, mobilized and advanced 2–3 cm distal to the fistula closure (Fig. 10.4). This flap is approximated with 3-0 absorbable interrupted sutures. A small segment of the distal flap is excised and the posterior flaps are advanced and closed beyond the fistula side with absorbable 2-0 interrupted suture to result in a four-layer closure (Fig. 10.5).

Fig. 10.4

The peritoneum is advanced distal to the fistula closure (Copyright © Shlomo Raz, MD)

Fig. 10.5

Repair and closure of the fistula with four layers (Copyright © Shlomo Raz, MD)

Latzko Partial Colpocleisis

The Latzko partial colpocleisis is an alternative technique to our transvaginal vesicovaginal fistula repair. Our approach avoids vaginal shortening and overlapping suture line that may result in recurrence. Other authors report low recurrence rates and vaginal shortening only when there is already a shortened vagina [58]. Potential advantages of this approach are decreased morbidity from less blood loss and shorter operating time. The Latzko technique is attempted for proximal post hysterectomy fistula. It involves a circumferential elliptoid incision around the fistula with wide mobilization of the vaginal epithelium in all directions. The fistula tract is closed and the repair is reinforced by an inverted layer of the perivesical tissue. The suture lines are overlapping in this repair (Figs. 10.6a–c and 10.7a–c).

Fig. 10.6

(a, b) Circumferential incision and mobilization of the vaginal epithelium around the fistula. (c) Closure of vaginal epithelium results in overlapping suture lines

Fig. 10.7

(a, b) Circumferential incision and dissection of the epithelium around the fistula with inverted closure of the fistula tract and perivesical tissue in two layers. (c) Closure of vaginal epithelium results in nonoverlapping suture lines (Copyright © Shlomo Raz, MD)

Abdominal Repair (Fig. 10.8a–e)

An abdominal approach may include open, laparoscopic or robotic repair. Indications for an abdominal approach include intraperitoneal pathology, concomitant ureteric reimplant, or bladder augmentation, or need for fecal diversion. Abdominal repair is typically approached with the O’Conor technique. Our standard approach begins with a midline incision that extends from the umbilicus to the pubic bone. Once entering the peritoneum the bladder is identified by retrograde filling of the catheter. A vaginal probe is inserted and retracted superiorly. The bladder is dissected free from the vagina until the fistulous tract is encountered. A decision to bivalve the bladder is made if the fistula tract is not visibly patent and open. The bladder is bivalved extending the incision to include the fistula which can be biopsied if there is concern for malignancy. The vaginal wall is dissected and separated from the bladder 3–4 cm surrounding the fistula. The bladder and the vagina are closed in two separate layers and indigo carmine is injected to assure complete closure. Interposition of tissue flap between the layers is added for security. The most described interposition is the omental flap which has increased success rates in retrospective studies or free flap of peritoneum can be used [16, 21].

Fig. 10.8

(a–e) Open approach for vesicovaginal fistula. (a) An incision is made in the anterior bladder wall and retraction sutures are placed to expose the fistula. Ureteral stents identify the ureters during repair. (b) The incision in the bladder is extended to include and excise the fistula tract. The vaginal tissue in the fistula tract is excised. (c) The bladder and vagina are separated using sharp dissection along the dotted line. This is a difficult plane to develop, but it is important to mobilize and separate the bladder and vagina for a successful repair. (d) The vagina is closed with tension-free interrupted sutures. (e) The bladder and vagina are closed in separate layers. Tissue can be interposed between the repairs at this time

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree