Background

Pregnancy may increase a woman’s susceptibility to HIV. Maternal HIV acquisition during pregnancy and lactation is associated with increased perinatal and lactational HIV transmission. There are no published reports of preexposure prophylaxis use after the first trimester of pregnancy or during lactation.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to report the use of preexposure prophylaxis and to identify gaps in HIV prevention services for women who were at substantial risk of HIV preconception and during pregnancy and lactation at 2 United States medical centers.

Study Design

Chart review was performed on women who were identified as “at significant risk” for HIV acquisition preconception (women desiring pregnancy) and during pregnancy and lactation at 2 medical centers in San Francisco and New York from 2010-2015. Women were referred to specialty clinics for women who were living with or were at substantial risk of HIV.

Results

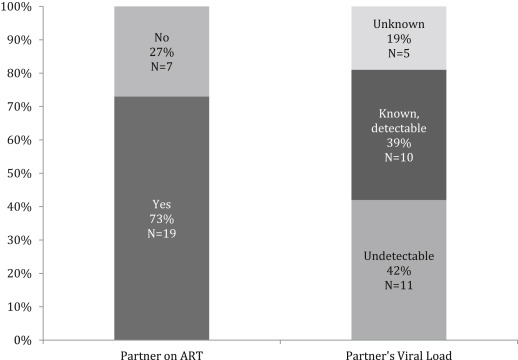

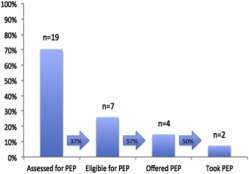

Twenty-seven women who were identified had a median age of 27 years. One-half of the women had unstable housing, 22% of the women had ongoing intimate partner violence, and 22% of the women had active substance use. Twenty-six women had a male partner living with HIV, and 1 woman had a male partner who had sex with men. Of the partners who were living with HIV, 73% (19/26) were receiving antiretroviral therapy, and 42% (11/26) had documented viral suppression. Thirty-nine percent (10/26) of partners had known detectable virus, and 19% (5/26) had unknown viral loads. Women were identified by clinicians, health educators, and health departments. Approximately one-third of the women were identified preconception (8/27); the majority of the women were identified during pregnancy (18/27) with a median gestational age of 20 weeks (interquartile range, 11–23), and 1 woman was identified in the postpartum period. None of the pregnant referrals had received safer conception counseling to reduce HIV transmission. Twenty-six percent of all women (7/27) were eligible for postexposure prophylaxis at referral, of whom 57% (4/7) were offered postexposure prophylaxis. In 30% (8/27), the last HIV exposure was not assessed and postexposure prophylaxis was not offered. The median time from identification as “at substantial risk” to consultation was 30 days (interquartile range, 2–62). Two women were lost to follow up before consultation. One woman who was identified as “at significant risk” was not referred because of multiple pregnancy complications. She remained in obstetrics care and was HIV-negative at delivery but was lost to follow up until 10 months after delivery when she was diagnosed with HIV. No other seroconversions were identified. Of referrals who presented and were offered preexposure prophylaxis, 67% women (16/24) chose to take it, which was relatively consistent whether the women were preconception (5/8), pregnant (10/15), or after delivery (1/1). Median length of time on preexposure prophylaxis was 30 weeks (interquartile range, 20–53). One-half of women (10/20) who were in care at delivery did not attend a postpartum visit.

Conclusion

Women at 2 United States centers frequently chose to use preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention when it was offered preconception and during pregnancy and lactation. Further research and education are needed to close critical gaps in screening for women who are at risk of HIV for pre- and postexposure prophylaxis eligibility and gaps in care linkage before and during pregnancy and lactation. Postpartum women are particularly vulnerable to loss-to-follow-up and miss opportunities for safe and effective HIV prevention.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the World Health Organization (WHO) recommend offering oral preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention to individuals at substantial risk. In 2015, the WHO published meta-analysis data that demonstrated that oral preexposure prophylaxis (compared with placebo) effectively reduces HIV acquisition in women with a risk ratio of 0.57 (95% confidence interval, 0.34–0.94). The same year, the CDC estimated 468,000 women in the United States were eligible for HIV preexposure prophylaxis, which was defined by having condomless sex in the previous 6 months with a man living with HIV, a man who has had sex with men, or a man who use intravenous drugs.

Observational studies suggest women may have increased susceptibility to HIV during pregnancy. A meta-analysis of 5 studies found an increased, but not statistically significant, odds ratio of HIV acquisition during pregnancy (odds ratio, 1.3; 95% confidence interval, 0.5–2.1). Biologic plausibility for increased HIV susceptibility during pregnancy has also been suggested.

The effect of HIV acquisition during pregnancy and lactation on perinatal and lactational transmission is profound. One study demonstrated a 15-fold increased risk of perinatal transmission in the setting of HIV acquisition during pregnancy when compared with women with chronic, treated HIV (adjusted odds ratio, 15.2; 95% confidence interval, 4.0–56.3). When HIV is acquired during lactation, a 4-fold increase in lactational transmission has been reported, when compared with women with chronic untreated HIV. Acute HIV occurred in 8% of US perinatal transmissions from 2005–2010.

In the setting of potentially increased HIV susceptibility during pregnancy and well-documented increased perinatal and lactational transmission with HIV acquisition during pregnancy or lactation, HIV prevention in and around pregnancy is paramount to caring for women and eliminating perinatal and lactational transmission. HIV prevention methods include condoms, treatment of partners with HIV as prevention, postexposure prophylaxis, preexposure prophylaxis, and treatment of sexually transmitted infections (STIs). For conception, timed intercourse and assisted reproduction provide additional options. Although treatment as prevention is likely the most efficacious, partner-dependent methods are not feasible or desirable for many women. As the only woman-controlled, discrete method to be taken in advance of exposure, preexposure prophylaxis provides a critical option for women.

In the only published studies that included women who incidentally became pregnant while receiving preexposure prophylaxis, drugs were stopped in the first trimester; no differences in pregnancy outcomes and postnatal growth were detected. The Antiretroviral Pregnancy Registry contains enough data on tenofovir and emtricitabine, which are the drugs recommended for preexposure prophylaxis (co-formulated as Truvada), to detect a 1.5-fold increase in anomalies with first-trimester exposures, but no such increase has been found. Supported by multiple studies that suggest safety in pregnancy, national guidelines recommend tenofovir/emtricitabine as first-line agents for pregnant women with HIV and tenofovir for pregnant women with hepatitis B. Data are very limited on lactational use, but pharmacokinetic studies suggest that infant exposure is lower through breast milk than in utero.

The WHO and CDC suggest offering preexposure prophylaxis use during pregnancy and lactation with discussion of risks and benefits. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists’ committee opinion on preexposure prophylaxis states tenofovir/emtricitabine has a “reassuring” safety profile in pregnancy and suggests clinicians be “vigilant” for HIV seroconversion during lactation. However, we are unaware of published data on the use of preexposure prophylaxis during pregnancy and lactation. This study reports usage of preexposure prophylaxis and identifies gaps in referrals and services for HIV prevention among women who are at substantial risk of HIV preconception and during pregnancy and lactation at 2 US medical centers from 2010–2015.

Methods

Two clinicians who were experienced with the provision of preexposure prophylaxis performed retrospective chart reviews at 2 academic medical centers in San Francisco, CA, and the Bronx, NY. All women identified to be at substantial risk of HIV preconception (including only women desiring to conceive), during pregnancy, or during the postpartum period (up to 1 year after delivery or the duration of lactation) and who were referred to specialty clinics for women living with or at substantial risk of HIV were included. If women had repeat pregnancies during the study period, earlier pregnancies were analyzed separately. One clinic was co-located in an obstetrics clinic, and 1 clinic was in an infectious disease clinic. Services at both clinics included multidisciplinary teams with intensive case management. Both offered full-spectrum safer conception counseling and HIV prevention options during pregnancy and lactation. If a woman took pre- or postexposure prophylaxis, both clinics generally followed CDC toxicity monitoring guidelines.

Chart extraction included details of the referral process, demographics, medical and social histories, HIV risk factors, pregnancy and postpartum data, HIV prevention methods that had been used, HIV testing, infant outcomes, and partners’ HIV status (when available). In 2008, the CDC recommended offering postexposure prophylaxis within 72 hours to all individuals, including pregnant and breastfeeding women, who had condomless sex with a person living with HIV ; women’s eligibility for and use of postexposure prophylaxis according to CDC criteria was also obtained. Descriptive statistics were performed. Univariate logistic regression was used to assess for association between demographic variables and assessment of postexposure prophylaxis eligibility and use of preexposure prophylaxis, respectively.

Chart review was also performed on records of women who were referred but did not attend the consultation or who had delayed referrals. Additional extracted data included circumstances under which women were identified and referred to identify missed opportunities to offer HIV prevention. Before data collection, the University of California San Francisco and Bronx Lebanon Hospital Center institutional review boards approved the study.

Results

Twenty-seven women were identified. The median age was 27 years old; 19% of the women were black, and 44% were Hispanic. Over one-half of the women had unstable housing (52%); 22% of the women actively used substances, and 22% of them had ongoing intimate partner violence ( Table ). Women were identified as at substantial risk of HIV by obstetricians (n=8), midwives (n=2), primary care providers (n=8), emergency department providers (n=1), male partners’ physicians (n=2), health educators (n=3), and health departments (n=3). The most common HIV risk factor was having a male partner living with HIV (26/27 women); 1 woman had a male partner with unknown HIV status who had sex with men. Notably, 15% of women (4/27) were identified when asked about their partners’ HIV risk factors in the setting of syphilis diagnoses in themselves or their male partners. Of the male partners known to be living with HIV, 73% of them were undergoing antiretroviral therapy (19/26); 42% of them had documented viral suppression (11/26); 39% of them had detectable viral loads (10/26), and 19% of them had unknown viral loads (5/26; Figure 1 ).

| Variable | Data |

|---|---|

| Median age, y (range) | 27 (18–43) |

| Median parity, n (range) | 1 (0–4) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Black | 5 (19) |

| White | 4 (15) |

| Latino | 12 (44) |

| Asian | 2 (7) |

| Other | 4 (15) |

| Graduated high school, n (%) | 9 (33) |

| Unstable housing or homeless, n (%) | 14 (52) |

| Current intimate partner violence, n (%) | 6 (22) |

| Current substance use, n (%) | 6 (22) |

| History of mental health disorder, n (%) | 12 (44) |

Less than one-third of women (8/27) were identified preconception, with the majority identified during pregnancy (18/27) and 1 during the postpartum period. Median time from identification to consultation was 30 days (interquartile range, 2–62). Two women were lost to follow up between identification and consultation. Of the women who were identified before conception, 1 had been referred previously for safer conception counseling to a high-risk obstetrician. Of the women who were identified during pregnancy, none reported preconception or safer conception counseling. The median gestational age at consultation among pregnant women was 20 weeks (interquartile range, 11–23).

At initial presentation, two-thirds of the records (19/27 women) documented the assessment of postexposure prophylaxis eligibility (HIV exposure within 72 hours). No association was identified between race, age, pregnancy status, or gestational age and assessment of postexposure prophylaxis eligibility (all P >.1). Of the 19 women whose records were assessed for postexposure prophylaxis eligibility, 37% were eligible; 57% of those were offered prophylaxis, and 50% of those chose to take postexposure prophylaxis ( Figure 2 ).

Two-thirds of the women (16/24) who were offered preexposure prophylaxis chose to use it. This proportion was relatively consistent whether women were preconception (5/8), pregnant (10/15), or postpartum (1/1). Choosing to take preexposure prophylaxis was not associated with age, race, pregnancy status, or gestational age (all P >.1). The median time on preexposure prophylaxis was 30 weeks (range, 4–74 weeks). One-half of the 16 women experienced adherence challenges (8/16), which included nausea and fatigue (2/8), social stressors (3/8), and difficulty adhering to a daily pill (3/8). From limited available postpartum data, no pregnancy complications or adverse infant outcomes were identified related to pre- or postexposure prophylaxis.

Approximately 40% of women chose to stop preexposure prophylaxis after conception (1/16) or delivery (6/16). Main reasons for stopping preexposure prophylaxis were not wanting to use it while breastfeeding (n=2), side-effects (n=1), adherence challenges (n=2), changes in insurance/cost (n=2), and attaining pregnancy after preexposure prophylaxis use for safer conception (n=1; Figure 3 ). Some women had multiple reasons for stopping preexposure prophylaxis.