Background

Clinical guidelines recommend that women with abnormal uterine bleeding with risk factors have an endometrial biopsy to exclude hyperplasia or cancer. Given the majority of endometrial cancer occurs in postmenopausal women, it has not been widely recognized that obesity is a significant risk factor for endometrial hyperplasia and cancer in young, symptomatic, premenopausal women.

Objective

We sought to evaluate the effect of body mass index on risk of endometrial hyperplasia or cancer in premenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding.

Study Design

This was a retrospective cohort study in a single large urban secondary women’s health service. Participants were 916 premenopausal women referred for abnormal uterine bleeding of any cause and had an endometrial biopsy from 2008 through 2014. The primary outcome was complex endometrial hyperplasia (with or without atypia) or endometrial cancer.

Results

Almost 5% of participants had complex endometrial hyperplasia or cancer. After adjusting for clinical and demographic factors, women with a measured body mass index ≥30 kg/m 2 were 4 times more likely to develop complex hyperplasia or cancer (95% confidence interval, 1.36–11.74). Other risk factors were nulliparity (adjusted odds ratio, 3.08; 95% confidence interval, 1.43–6.64) and anemia (adjusted odds ratio, 2.23; 95% confidence interval, 1.14–4.35). Age, diabetes, and menstrual history were not significant.

Conclusion

Obesity is an important risk factor for complex endometrial hyperplasia or cancer in premenopausal women with abnormal uterine bleeding who had an endometrial biopsy in a secondary gynecology service. As over half of women with the outcome in this study were age <45 years, deciding to biopsy primarily based on age, as currently recommended in national guidelines, potentially misses many cases or delays diagnosis. Body mass index should be the first stratification in the decision to perform endometrial biopsy and/or to refer secondary gynecology services.

Introduction

Abnormal uterine bleeding (AUB) such as heavy or irregular vaginal bleeding of any cause, is the most common reason for referral to a gynecologist, and frequently leads to an invasive diagnostic test such as endometrial biopsy or hysteroscopy. In a large study of premenopausal women with AUB referred for an endometrial biopsy, the prevalence of complex endometrial hyperplasia or cancer was 3.0%.

Endometrial hyperplasia is a precursor to endometrial cancer and is thought to result from persistent, prolonged, unopposed estrogenic stimulation of the endometrium, the most common cause being a succession of anovulatory cycles. Anovulation occurs most often during the perimenopause, or in women with polycystic ovarian syndrome or obesity. An important distinction in the evaluation of hyperplasia is whether or not nuclear atypia is present. Women with complex hyperplasia with atypia are at risk of progression to endometrial cancer and as many as 28% of cases will progress over time to cancer and up to 43% of cases have unrecognized concurrent carcinoma at the time of biopsy.

Commonly recognized risk factors for endometrial cancer include age, obesity, nulliparity, infertility, and late-onset menopause. Family history of hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer is another risk factor. Diabetes and hypertension are frequently associated with endometrial cancer, while smoking and use of combined oral contraceptive pill are thought to be protective.

Over the past 2 decades there has been global recognition of increasing levels of obesity. At the same time, there is epidemiological evidence of increased incidence of endometrial cancer. Several systematic reviews have shown an association between obesity and endometrial cancer. However, given that the majority of endometrial cancer occurs in postmenopausal women, it has not been widely recognized that obesity is a significant risk factor for endometrial hyperplasia and cancer in young, symptomatic, premenopausal women.

Developing a greater understanding of the leading risk factors for premenopausal women would lead to improved clinical pathways from primary to secondary care and improved targeting of invasive diagnostic testing. The objective of the current study was to evaluate the association of body mass index (BMI) and endometrial complex hyperplasia or cancer in premenopausal women with AUB who had an endometrial biopsy, adjusting for clinical and demographic factors. We hypothesized that obese women would be more likely to have complex hyperplasia or cancer compared to normal-weight women.

Materials and Methods

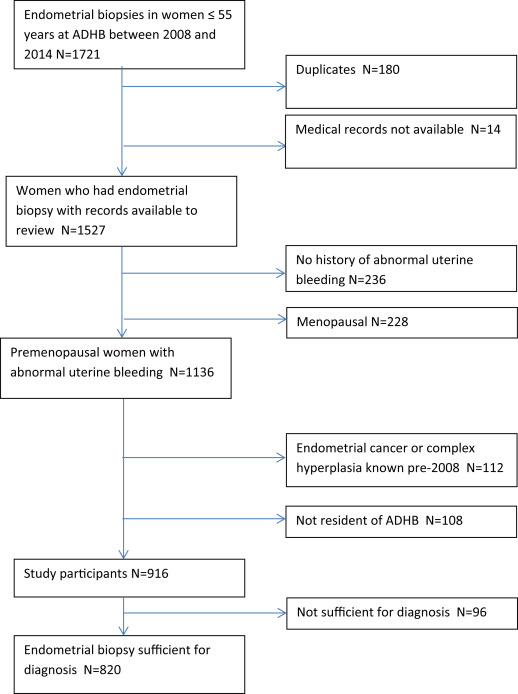

This was a retrospective cohort study including women age ≤55 years who had an endometrial biopsy at Auckland District Health Board from 2008 through 2014. Women were included if they had a history of AUB (clinical diagnosis by the referring doctor, including structural and nonstructural causes) and were not menopausal (either recorded as menopausal in the clinical record, or amenorrhea ≥6 months, or serum follicle-stimulating hormone level >20 IU/L). Women were excluded if they were known prior to 2008 to have had endometrial cancer. Women who were not residents of Auckland District Health Board were also excluded due to the referral pattern of surrounding district health boards to Auckland for tertiary cancer services. The primary study outcome was histologic diagnosis of endometrial biopsy of complex hyperplasia, complex atypical hyperplasia, or endometrial cancer, as stated in the pathology report.

Participants were identified from the hospital laboratory database of all inpatient and outpatient samples. The National Health Identifier was used to directly link with the hospital electronic medical records and clinical and demographic data were collected. The following clinical variables were collected: age, BMI, parity, self-reported use of hormone therapy, menstrual history, infertility (>12 months), medical history (smoking, diabetes, breast cancer, colorectal cancer), and family history (breast, colorectal, or endometrial cancer). Recent investigations (hemoglobin, pelvic ultrasound scan) and subsequent hysterectomy were also recorded.

Endometrial biopsy was performed by Pipelle (Pipelle De Cornier, Laboratoire CCD, Paris, France), sharp curettage, or both. If >1 biopsy was performed within 6 months, the one resulting in the most serious diagnosis was considered the final outcome. If a hysterectomy was performed within 6 months of the biopsy, the hysterectomy histology was considered the final outcome. The exception to this was in the setting where the biopsy reported hyperplasia, there was clear documentation that the patient was treated with progestogen in the interim, and the hysterectomy histology was normal. In that case, due to the known effectiveness of progestogen in treating endometrial hyperplasia, then the original biopsy result was considered the final outcome.

Self-reported ethnicity was collected at hospital registration with a standard New Zealand (NZ) census question. The concept of ethnicity adopted by Statistics NZ is a social construct of group affiliation and identity. The present statistical standard for ethnicity states that ethnicity is the ethnic group or groups that people identify with or believe they belong to; thus, ethnicity is self-perceived and people can belong to >1 ethnic group. If >1 ethnicity was reported, it was prioritized using the NZ Ministry of Health protocol.

Height and weight measurements used for calculating BMI were measured within 1 year of biopsy. Standard World Health Organization criteria were used to categorize BMI (normal 18.5–24.9 kg/m 2 , overweight 25–29.9 kg/m 2 , obese ≥30 kg/m 2 ). Socioeconomic status was estimated using the NZ deprivation score based on recorded maternal place of residence. Deprivation centiles (1–10) were condensed into quintile scores from 1 (least deprived) to 5 (most deprived).

Data analysis

We determined the overall incidence of endometrial complex hyperplasia or cancer and compared crude rates across each clinical and demographic variable using simple logistic regression. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence limits were estimated for each of these associations. In all cases, a P value of .05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariable analysis using logistic regression was performed to assess the independent association between each variable and the outcome. Included in the multivariable model were BMI and age (for a priori reasons) and those factors significantly associated with the outcome on univariate analysis.

As ethnicity and BMI are highly correlated in this population, only 1 of these variables was able to be retained in the multivariable model. We chose BMI as: (1) it meant a smaller number of degrees of freedom (2 vs 5), and (2) the use of BMI is more generalizable to other populations. Endometrial thickness was missing in one third of participants, hence we produced multivariable models both excluding and including endometrial thickness. Further sensitivity analysis was performed using the outcome of complex atypical hyperplasia or cancer. Data analysis was performed in software (SAS, Version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Based on a power of 80%, a level of significance of 5%, and an estimated prevalence of complex hyperplasia or cancer 3.0% and of obesity 30% (in the previous NZ study), the current study with a sample of 840 subjects had the power to detect a relative risk of 1.89.

This study was approved on Oct. 5, 2012, by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (Ref. 8651).

Materials and Methods

This was a retrospective cohort study including women age ≤55 years who had an endometrial biopsy at Auckland District Health Board from 2008 through 2014. Women were included if they had a history of AUB (clinical diagnosis by the referring doctor, including structural and nonstructural causes) and were not menopausal (either recorded as menopausal in the clinical record, or amenorrhea ≥6 months, or serum follicle-stimulating hormone level >20 IU/L). Women were excluded if they were known prior to 2008 to have had endometrial cancer. Women who were not residents of Auckland District Health Board were also excluded due to the referral pattern of surrounding district health boards to Auckland for tertiary cancer services. The primary study outcome was histologic diagnosis of endometrial biopsy of complex hyperplasia, complex atypical hyperplasia, or endometrial cancer, as stated in the pathology report.

Participants were identified from the hospital laboratory database of all inpatient and outpatient samples. The National Health Identifier was used to directly link with the hospital electronic medical records and clinical and demographic data were collected. The following clinical variables were collected: age, BMI, parity, self-reported use of hormone therapy, menstrual history, infertility (>12 months), medical history (smoking, diabetes, breast cancer, colorectal cancer), and family history (breast, colorectal, or endometrial cancer). Recent investigations (hemoglobin, pelvic ultrasound scan) and subsequent hysterectomy were also recorded.

Endometrial biopsy was performed by Pipelle (Pipelle De Cornier, Laboratoire CCD, Paris, France), sharp curettage, or both. If >1 biopsy was performed within 6 months, the one resulting in the most serious diagnosis was considered the final outcome. If a hysterectomy was performed within 6 months of the biopsy, the hysterectomy histology was considered the final outcome. The exception to this was in the setting where the biopsy reported hyperplasia, there was clear documentation that the patient was treated with progestogen in the interim, and the hysterectomy histology was normal. In that case, due to the known effectiveness of progestogen in treating endometrial hyperplasia, then the original biopsy result was considered the final outcome.

Self-reported ethnicity was collected at hospital registration with a standard New Zealand (NZ) census question. The concept of ethnicity adopted by Statistics NZ is a social construct of group affiliation and identity. The present statistical standard for ethnicity states that ethnicity is the ethnic group or groups that people identify with or believe they belong to; thus, ethnicity is self-perceived and people can belong to >1 ethnic group. If >1 ethnicity was reported, it was prioritized using the NZ Ministry of Health protocol.

Height and weight measurements used for calculating BMI were measured within 1 year of biopsy. Standard World Health Organization criteria were used to categorize BMI (normal 18.5–24.9 kg/m 2 , overweight 25–29.9 kg/m 2 , obese ≥30 kg/m 2 ). Socioeconomic status was estimated using the NZ deprivation score based on recorded maternal place of residence. Deprivation centiles (1–10) were condensed into quintile scores from 1 (least deprived) to 5 (most deprived).

Data analysis

We determined the overall incidence of endometrial complex hyperplasia or cancer and compared crude rates across each clinical and demographic variable using simple logistic regression. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence limits were estimated for each of these associations. In all cases, a P value of .05 was considered statistically significant. Multivariable analysis using logistic regression was performed to assess the independent association between each variable and the outcome. Included in the multivariable model were BMI and age (for a priori reasons) and those factors significantly associated with the outcome on univariate analysis.

As ethnicity and BMI are highly correlated in this population, only 1 of these variables was able to be retained in the multivariable model. We chose BMI as: (1) it meant a smaller number of degrees of freedom (2 vs 5), and (2) the use of BMI is more generalizable to other populations. Endometrial thickness was missing in one third of participants, hence we produced multivariable models both excluding and including endometrial thickness. Further sensitivity analysis was performed using the outcome of complex atypical hyperplasia or cancer. Data analysis was performed in software (SAS, Version 9.4; SAS Institute Inc, Cary, NC).

Based on a power of 80%, a level of significance of 5%, and an estimated prevalence of complex hyperplasia or cancer 3.0% and of obesity 30% (in the previous NZ study), the current study with a sample of 840 subjects had the power to detect a relative risk of 1.89.

This study was approved on Oct. 5, 2012, by the University of Auckland Human Participants Ethics Committee (Ref. 8651).

Results

The study cohort comprised 916 women who met the inclusion and exclusion criteria ( Figure 1 ). Half of the women were obese. Obese women were more likely to be <40 years old, of Māori and Pacific ethnicity, and residing in areas of high deprivation. Characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1 .

| BMI <30 | BMI ≥30 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 465 | % | N = 451 | % | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||

| Age, y | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 43.7 ± 6.4 | 42.0 ± 7.2 | ||

| <40 | 87 | 18.7 | 137 | 30.4 |

| 40–44 | 139 | 29.9 | 119 | 26.4 |

| 45–49 | 163 | 35.0 | 137 | 30.4 |

| 50–55 | 73 | 15.7 | 57 | 12.6 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| European | 158 | 34.0 | 82 | 18.2 |

| Māori | 36 | 7.7 | 80 | 17.8 |

| Pacific | 18 | 3.9 | 213 | 47.3 |

| Indian | 83 | 17.8 | 35 | 7.8 |

| Asian | 112 | 24.1 | 22 | 4.9 |

| Other | 58 | 12.5 | 18 | 4.0 |

| NZ deprivation score | ||||

| 1–2 | 44 | 12.6 | 16 | 4.9 |

| 3–4 | 65 | 18.7 | 52 | 15.9 |

| 5–6 | 78 | 22.4 | 56 | 17.1 |

| 7–8 | 87 | 25.0 | 88 | 26.9 |

| 9–10 a | 74 | 21.3 | 115 | 3 |

| Weight, kg | ||||

| Mean ± SD | 65.9 ± 10.2 | 104.8 ± 24.5 | ||

| Clinical characteristics | ||||

| Menstrual history | ||||

| Mean duration of AUB, y (mean ± SD) | 3.4 ± 4.1 | 3.8 ± 5.4 | ||

| Menstrual cycle regularity | ||||

| Regular | 203 | 44.7 | 157 | 35.4 |

| Irregular | 209 | 46.0 | 254 | 57.2 |

| Menstrual cycle duration, d | ||||

| <7 | 211 | 47.0 | 170 | 38.6 |

| 7–14 | 83 | 18.5 | 78 | 17.7 |

| >14 | 53 | 11.8 | 80 | 18.2 |

| Intermenstrual bleeding | ||||

| Yes | 131 | 28.8 | 82 | 18.6 |

| Hormonal therapy (current, recent) | ||||

| COCP | 29 | 6.2 | 15 | 3.3 |

| Progestogen | 112 | 24.1 | 170 | 37.7 |

| Tamoxifen | 3 | 0.6 | 2 | 0.4 |

| Pregnancy history | ||||

| Nulliparity | 69 | 14.8 | 67 | 14.9 |

| Infertility | 20 | 4.5 | 33 | 7.6 |

| Medical history | ||||

| Diabetes | 26 | 5.7 | 63 | 14.0 |

| Breast cancer | 8 | 1.7 | 7 | 1.6 |

| Colorectal cancer | 1 | 0.2 | 1 | 0.2 |

| Smoking (current) | 50 | 10.9 | 92 | 20.7 |

| Family history of cancer | ||||

| Endometrial | 10 | 2.2 | 14 | 3.1 |

| Breast | 21 | 4.5 | 24 | 5.3 |

| Colorectal | 19 | 4.1 | 10 | 2.2 |

| Anemia | ||||

| Yes | 148 | 32.9 | 202 | 46.6 |

| Pelvic ultrasound scan | ||||

| Submucous fibroid | 35 | 7.5 | 18 | 4.0 |

| Polyp | 33 | 7.1 | 32 | 7.1 |

| Endometrial thickness, mm | ||||

| Mean | 16.5 ± 44.6 | 26.0 ± 126.5 | ||

| ≥12 mm | 117 | 38.0 | 156 | 49.8 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree