Urologic Abnormalities of the Genitourinary Tract

Luis H. P. Braga and Darius J. Bägli

ANOMALIES OF THE KIDNEY AND URETER

URETEROPELVIC JUNCTION OBSTRUCTION

Obstruction of the flow of urine from the renal pelvis to the proximal ureter due to ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) is the most common cause of hydronephrosis in infancy and childhood.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction is most often caused by an intrinsic narrowing at the junction of the renal pelvis and ureter. Extrinsic compression by an aberrant crossing vessel or fibrous band is a less common etiology, usually being responsible for obstruction in older children. The obstruction initially leads to an increased intrapelvic pressure and accumulation of urine proximal to the site of obstruction, resulting in pelvicalyceal dilation. Long-standing severe obstruction will lead to progressive deterioration in renal function or hamper normal renal development.

DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

Most cases of ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction are detected by prenatal ultrasonography. Management approaches are discussed in Chapter 469. UPJ obstruction is suspected when only the renal pelvis is dilated without accompanying dilatation of the ureter. A voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) may be required to exclude vesicoureteral reflux, which can also produce significant hydronephrosis. UPJ obstruction may be asymptomatic or presents with age-dependent symptoms and signs. In infants, it may present with a palpable abdominal mass that must be differentiated from other causes of abdominal masses in the newborn. In older children, it may cause pain, hematuria, hypertension, and urinary tract infections. Initially, flank or abdominal pain may be attributed to gastrointestinal disease because the pain follows ingestion of liquids, which causes distention of the renal pelvis. It may also cause periodic severe episodes of vomiting that present with a cyclic vomiting pattern. When the renal pelvis is very dilated from UPJ, hematuria may occur post trauma.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

The management of prenatally suspected ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction is conservative in most cases. A renal ultrasound obtained too soon after delivery, within the first 3 days, may underestimate the degree of dilatation because of the low newborn urine output during the first days of life. In most cases, a renal ultrasound should be obtained after the first week and within the first month. Up to two thirds of prenatally suspected UPJ obstructions will have preserved renal function. Some infants show improvement and even resolution of the obstruction over the first 24 months of life. The degree of obstruction and the differential function of the affected kidney, as determined by diuretic renography, as well as the trend observed by serial ultrasounds help confirm the diagnosis and direct subsequent management.1 Early laparoscopic pyeloplasty, although uncommon today, is indicated if the postnatal evaluation yields evidence of functional impairment (relative function of involved side < 30–40% of total function) and/or massive dilation of renal pelvis (anteroposterior [AP] diameter > 30 mm), signs of severe obstruction bilaterally or in a solitary kidney.2 Conservative management is indicated if the relative function of the affected kidney is greater than 40%, and is appropriate in the great majority of mild and moderate hydronephrosis cases. Indications to abandon conservative management in favor of pyeloplasty include deteriorating renal function, increasing hydronephrosis, development of symptoms (pain), and/or pyelonephritis. Although there has been a trend away from prophylactic antibiotic usage in isolated UPJ obstruction, the very young infant with severe dilation may benefit from such chemoprotection.

URETERAL DUPLICATION

Duplication is the most common structural anomaly of the upper urinary tract, affecting 1 in 160 individuals. Ureteral duplication can be complete or partial. When complete ureteral duplication exists, the medial and distal ureteral orifices drain the upper moiety, and the lateral and proximal orifices drain the lower moiety of the kidney, respectively (Meyer-Weigert law).

The majority of complete and partial duplications remain asymptomatic and undetected, and are considered normal variants. Symptoms occur as the result of vesicoureteral reflux (predominantly to the lower pole system—due to the laterality of the lower pole orifices), ureteropelvic junction (UPJ) obstruction (usually involving the lower pole system), obstruction (resulting from the presence of a ureterocele usually involving the upper pole system), or ureteric ectopia (with associated obstruction or incontinence). Because the majority of uncomplicated duplications are not associated with dilatation, detection by ultra-sonography is difficult. Management depends on the degree of vesicoureteral reflux, presence of an ureterocele, function of the affected system, and development of urinary tract infection.

URETERAL ECTOPIA

Ectopic ureters are rare in boys and usually present with urinary infection or epididymoorchitis. The ureter can drain into the vas deferens, seminal vesicles, prostatic urethra, or distal trigone. Because these locations are proximal to the external sphincter, continence is preserved. In girls, the possibility of an ectopic ureter must be considered when a lifelong history of urinary incontinence (dampness) is present. The ureter can drain into the bladder neck, urethra, vagina, uterus, fallopian tubes, or vestibule. That some of these locations are distal to the urinary sphincter explains the lifelong history of incontinence, both daytime and nighttime, which often occurs. Ectopic ureter should be suspected whenever a girl complains of consistently damp undergarments despite normal voiding habits.

MEGAURETER

Wide and dilated (> 7 mm) ureters are referred to as megaureters and are classified as refluxing or nonrefluxing or obstructive or nonobstructive, and are subdivided into primary and secondary types. Presently, megaureters account for 10% of infants with prenatally detected uropathy. Prior to most megaureter being diagnosed on prenatal ultrasound, obstructed megaureters presented with urinary tract infections, flank pain, or calculi.

A primary obstructed nonrefluxing megaureter is the result of a stenotic, aperistaltic segment of the distal ureter at the level of the ureterovesical junction. Secondary obstructed nonrefluxing megaureters can result from neurogenic bladder, an obstructing ureterocele, or a tumor involving the bladder outlet or ureteral orifice. A primary refluxing megaureter, which can be obstructed or nonobstructed, is a congenital anomaly associated with an inadequate ureteral tunnel length at the ureterovesical junction and is more likely to be bilateral than unilateral. Secondary refluxing megaureters occur as a result of urodynamic abnormalities involving the bladder or urethra, such as neurogenic bladder, posterior urethral valves, or ureteroceles. At times, reflux and obstruction may coexist in the same ureter. The primary etiologic factor may need to be addressed in the management of secondary obstructed or refluxing megaureters. The diagnosis of a nonrefluxing nonobstructed megaureter is one of exclusion. The primary cause of this condition is unknown; spontaneous resolution of the ureteral dilatation can occur.

The majority of infants with prenatally detected obstructed megaureters can be managed conservatively because they are asymptomatic, and their obstruction is often associated with preserved renal function. Close observation is required to detect any deterioration of renal function. Management of megaureters is based on the results of ultrasonography, voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG), and/or diuretic renography. In one study, less than one third of children with an antenatal diagnosis of megaureter underwent surgery.3 Surgery is directed toward removal of the obstruction, and as necessary, correction of the reflux. With primary refluxing megaureters, intervention is required in those patients with recurrent infections. In cases of primary obstructing nonrefluxing megaureters, indications for intervention include progressive hydronephrosis, parenchymal loss, and recurrent infections.

URETEROCELE

A ureterocele is a cystic dilation of the intravesical submucosal ureter and can be associated with a single system or, more commonly, with a duplex system. Ureteroceles are believed to represent a developmental defect resulting from incomplete dissolution of Chwalla membrane that causes an obstruction of the ureteral–meatal orifice. Girls are affected four to seven times more commonly than boys.

Ureteroceles are classified as intravesical (contained entirely within the bladder) or ectopic (located at the bladder neck or extending into the urethra). Ureteroceles vary in size and may obstruct their upper pole moiety, both upper and lower pole ipsilaterally, or the contralateral ureter. They may also distort the trigone, causing vesicoureteral reflux, or obstruct the bladder neck and urethra, the latter occurring more frequently in boys. Ureteroceles that are associated with a duplex system (80% of cases) usually drain the upper pole of the kidney.

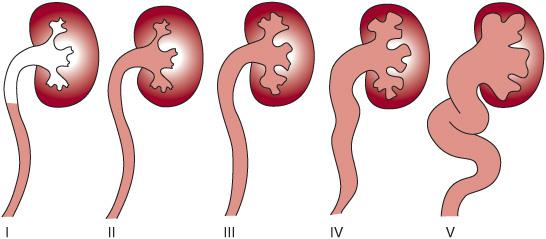

FIGURE 476-1. International Reflux Study classification system for vesicoureteral reflux. Grade I describes reflux into the distal ureter only, whereas grade II consists of reflux into the collecting system without distension of the calices. In grade III, reflux is present in a minimally dilated ureter and collecting system with distension of calices. Grade IV is reflux into a dilated ureter with blunting of calyceal fornices, and grade V is massive reflux with significant ureteral dilatation and tortuosity with loss of papillary impression.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT

Many single-system ureteroceles are small and asymptomatic, and are noted on ultrasound or voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG). In the absence of obstruction or recurrent infection, no treatment is necessary. Ureteroceles associated with a duplex system are frequently detected by prenatal ultrasonography, or present clinically with a febrile urinary tract infection. A VCUG is necessary to evaluate the presence of vesicoureteral reflux (found in the lower pole in about 50% of cases), and nuclear renography is helpful in assessing the degree of function of the affected kidney. The choice of strategy for the treatment of ureteroceles is based on the age of the patient, the amount of functioning renal parenchyma, whether the kidney is single or duplex, the location of the ureterocele, and the presence of vesicoureteral reflux. In the past, definitive surgical management included an upper pole partial nephrectomy with or without reimplantation of the ureter draining the lower segment. Endoscopic management with transurethral incision or puncture of ureteroceles is less invasive and, currently, has become the first approach for infants and children with intravesical ureteroceles requiring intervention.4

VESICOURETERAL REFLUX

VESICOURETERAL REFLUX

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) represents the retrograde flow of urine from the bladder into the ureters and renal pelvis. VUR is graded from I to V according to the International Reflux Study classification system (Fig. 476-1).5

PRENATAL VESICOURETERAL REFLUX

Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is described in 9% to 38% of neonates with prenatal hydronephrosis, using somewhat nonspecific ultrasound findings of intermittent dilatation of the collecting system during the sonographic study. Fluctuation of the renal pelvis on antenatal ultrasound was more recently shown to serve as a marker for persistent high-grade VUR and renal damage in both boys and girls. In this setting, it is seen more commonly in boys (about 90% of cases) with ureteral dilation and bladder abnormalities; it is characterized by bilateral high-grade VUR (grades IV and V) due to detrusor instability and relatively high voiding pressures and associated renal dysplasia, and shows high spontaneous resolution rates. The diagnosis of reflux is confirmed with a postnatal voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG). Forty percent of neonates with VUR already have features indicative of renal dysmorphism on DMSA (dimercaptosuccinic acid) scan prior to any episode of urinary tract infection, suggesting that congenital renal maldevelopment associated with reflux is an important cause of scintigraphic abnormalities in the absence of any infection process. In general, refluxing renal units with normal parenchyma are expected to have their VUR resolve spontaneously by the age of 30 months, but this may vary according to reflux grade and management of concomitant bladder dysfunction.

VESICOURETERAL REFLUX IN THE OLDER CHILD

VESICOURETERAL REFLUX IN THE OLDER CHILD

In older children, vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is most frequently diagnosed after an infection and is more prevalent in girls (3:1). Usually, kidneys are normal but are more prone to recurrent urinary tract infections due to bladder dysfunction and have a lower spontaneous resolution rate when compared to male infants.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

Newborns with vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) should receive long-term antibiotic prophylaxis while waiting for spontaneous resolution of the reflux, although more recent studies question the benefit of this approach in children with less severe VUR.6 There has been is a gradual trend to stop antibiotic prophylaxis in children with VUR after they become toilet trained, recognizing that scar formation is less common in patients older than 5 years. It is uncertain whether antibiotic prophylaxis of children with VUR confers clinically important benefit.7 Circumcision has been shown to likely reduce the risk of urinary tract infection substantially in children with VUR.8 This may be recommended along with antibiotic prophylaxis for boys with high-grade VUR.

Occurrence of breakthrough urinary tract infections and sound documentation of progressive postinfection renal scarring continue to be the main indications for surgical correction of VUR. Currently, endoscopic correction of reflux with injection of bulking agents is evolving rapidly, but the gold standard procedure to correct reflux remains the classical intra- or extravesical ureteral reimplantation.

ANOMALIES OF THE BLADDER AND URETHRA

POSTERIOR URETHRAL VALVES

Posterior urethral valves are a congenital pair of obstructing leaflets in the region of the verumontanum in the prostatic urethra. The etiology is unclear, but they may form when the ventrolateral folds of the urogenital sinus fail to regress. Obstruction from urethral valves increases voiding pressures that result in dilatation of the prostatic urethra, hypertrophy of the bladder neck, bladder trabeculation, vesicoureteral reflux, renal dysplasia, and loss of renal function. The degree of obstruction creates a spectrum of damage and, consequently, a wide range of clinical presentations. Posterior urethral valves (PUV) are the most common cause of lower urinary obstruction in male infants and the most common type of obstructive uropathy leading to childhood renal failure. The incidence of PUV is 1 in 5000 to 8000 male infants.

DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

Most infants with posterior urethral valves (PUV) are identified with bilateral hydroureteronephrosis on prenatal ultrasonography. The classical “keyhole” appearance on antenatal sonographic evaluation is very suggestive of PUV and represents the dilated posterior urethra (small hole) and the bladder (large hole). Other causes of bilateral hydroureteronephrosis include prune belly syndrome, vesicoureteral reflux, and bilateral ureterovesical junction (UVJ) obstruction. After birth, the diagnosis is confirmed with a voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG). If the diagnosis is not detected on prenatal ultrasonography, the infant may present with a wide range of signs and symptoms, including delayed voiding, a distended bladder, palpable kidneys, a poor urinary stream with dribbling, or urosepsis. Constitutional symptoms such as abdominal distension, failure to thrive, and vomiting may occur. An infant may present with signs of renal failure such as hyponatremia and hyperkalemia. Later in childhood, nonspecific voiding problems such as incontinence, nocturnal enuresis, frequency, and recurrent urinary tract infections may result from PUV.

Massive unilateral vesicoureteral reflux is a unique entity seen in PUV patients and is termed valve, unilateral, reflux, and dysplasia (VURD) syndrome. Because of the pressure pop-off afforded by the refluxing kidney, the contralateral kidney is protected, the ipsilateral side takes the brunt of the increased voiding pressure, and patients with VURD syndrome usually have a better prognosis in regard to end-stage renal function when compared to children with a PUV presentation involving compromise of both kidneys.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

Although the relief of obstruction in utero had theoretical benefit, treatment trials have shown no long-term benefit.9,10 Treatment of fetal-diagnosed posterior urethral valves (PUV) at birth is critical to relieve the obstruction. Immediate stabilization of the baby with bladder drainage is mandatory. It is preferable to insert a 6F feeding tube instead of a Foley catheter, as the tube lumen is larger, and the lack of a balloon reduces bladder instability. Sepsis, electrolyte abnormalities, acidemia, and fluid imbalance demand aggressive management. After stabilization of the infant, primary transurethral valve ablation is performed when technically feasible.10 If the urethra is too small to accept an infant cystoscope, a temporary vesicostomy may be performed. High diversion with loop ureterostomies is reserved for infants whose renal function continues to deteriorate despite bladder drainage; this condition is often indicative of intrinsically poor renal development and future function. Older boys can almost always undergo primary transurethral valve ablation because urethral size is not an issue, and overall renal function is usually better preserved.

Long-term complications from PUV include the development of bladder dysfunction and onset of renal insufficiency. Bladder dysfunction may be manifest by detrusor instability and a small noncompliant bladder. Some patients will develop the so-called “valve bladder” syndrome, which is characterized by persistent hydroureteronephrosis in the absence of an ureterovesical junction (UVJ) obstruction and is related to a small-capacity, high-pressure bladder. Some patients can be managed effectively with double voiding or anticholinergic medication and clean intermittent catheterization. If bladder capacity and hydroureteronephrosis do not improve, surgical bladder augmentation may be required. The incidence of end-stage renal disease in PUV is approximately 25%. A useful predictor of renal failure is the nadir serum creatinine at 1 year of age. A serum creatinine < 0.8 g/dL after the age of 1 makes renal failure less likely.11

PRUNE BELLY SYNDROME

The prune belly syndrome is a complex consisting of congenital absence or deficiency of abdominal wall musculature, bilateral cryptorchidism, and anomalies of the urogenital tract, mainly, dilation of the prostatic urethra, bladder, and ureters. The syndrome is also known as the triad syndrome or the Eagle-Barrett syndrome. It is believed to result from urethral obstruction early in development that results in urinary ascites with degeneration of the abdominal wall musculature, lack of pulmonary development, and failure of testicular descent. Impaired passage of urine from the bladder leads to oligohydramnios, pulmonary hypoplasia, and Potter facies.12 Female patients cannot develop cryptorchidism and therefore have an incomplete form of the pheno-type and account for approximately 5% of cases.

The severity of pulmonary involvement and renal disease affects outcome. Death in the perinatal period is more likely in the most severe expression of the process with pulmonary hypoplasia, complete urethral obstruction (without a patent urachus), and renal insufficiency. Advances in neonatal intensive care have improved the survival for some of these infants, but the prognosis remains poor. In newborns with prune belly syndrome (and a patent urachus), the severity of pulmonary hypoplasia is reduced due to the absence of urinary ascites. These infants often have moderate to severe renal insufficiency and failure to thrive. The clinical course is one of either renal stabilization or progressive loss of renal function culminating in renal transplantation. Those infants with prune belly syndrome and an absence or deficiency of the abdominal musculature with undescended testes but normal renal function despite an abnormal urinary tract comprise the majority of children with prune belly syndrome, and they do not develop significant renal impairment.

DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT

DIAGNOSIS AND MANAGEMENT

Often, diagnosis is made prenatally by ultrasound. The most obvious defect in newborns with the syndrome is the rugated, prunelike appearance of the abdominal wall, often with visible peristalsis of bowel loops. As the child begins to stand, a pear-shaped or pot-bellied appearance occurs. Evaluation for other anatomic abnormalities, pulmonary function, and renal function is required to predict outcome. The weakness of the abdominal musculature limits respiratory effort and may result in developmental delay in motor activities associated with axial balance. Recurrent respiratory infections and chronic constipation occur due to an impaired cough and strain from the lack of abdominal musculature.

Abnormalities of the urinary tract are the major factors affecting the prognosis of children with prune belly syndrome. Typical radiologic features include elongated, tortuous, and dilated ureters that have poor or absent peristalsis and a large-capacity, smooth-walled bladder with a patent urachus. Vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is present in 70% of cases. The posterior urethra is dilated, and the prostate is absent or hypoplastic.

Abnormalities in the epididymis, seminal vesicles, and vas deferens, in addition to the bilateral cryptorchidism, may be responsible for the infertility uniformly seen with this syndrome. The anterior urethra is usually normal; however, abnormalities range from urethral atresia to a fusiform or scaphoid megalourethra. Renal dysplasia and multicystic dysplastic kidney (MCDK) are common, and the extent of renal parenchymal involvement determines ultimate renal function. Bilateral cryptorchidism is a consistent finding of prune belly syndrome. The location of the testes is usually at the level of the iliac vessels in an apparent intraperitoneal position on a long mesorchium.

Varied approaches to the management of prune belly syndrome have been advocated, including trials of fetal therapy with combined vesicocentesis and amnioinfusion, but these approaches are not yet validated.13 The goals of early management are to preserve renal function and pulmonary health, as well as to prevent infection of both. Invasive procedures may complicate treatment of urinary tract infections and should be avoided if possible. Many infants require no early intervention. The dilatation of the urinary tract in prune belly syndrome is usually a low-pressure, nonobstructive system. However, if during the newborn period, renal function deteriorates secondary to obstructive uropathy, intervention may become warranted. Temporary urinary diversion with a vesicostomy or cutaneous pyelostomy may be employed. More extensive reconstructive surgery (reduction cystoplasty and excision of distal ureters with tapering and reimplantation of the healthier upper portion of the ureters into the bladder) may be performed in an effort to reduce stasis and prevent urinary tract infections in carefully selected older children. Early orchiopexy is advocated and may be performed in conjunction with reconstructive surgery or at the time of an abdominoplasty. Patients are usually placed on antibiotic prophylaxis to prevent urinary tract infections.

EPISPADIAS-EXSTROPHY COMPLEX

The epispadias-exstrophy complex is the result of a persistent cloacal membrane that does not retract normally toward the perineum. The persistent membrane prevents medial mesenchymal ingrowth, causing the future abdominal wall to remain laterally placed. With dehiscence of the cloacal membrane, the posterior wall of the bladder becomes exposed to the exterior on the surface of the abdominal wall. Bladder exstrophy is almost always accompanied by epispadias. Epispadias alone results if persistence of the cloacal membrane occurs only inferiorly.

The most common anomaly in this complex is classic bladder exstrophy, occurring in 1 in 30,000 to 40,000 births with a male preponderance. The risk of recurrence in a given family is 1%. The typical features include a defect in the abdominal wall from the umbilicus inferiorly, with the bladder open and exposed to the exterior. The bony pelvis is shallow and does not make a complete ring, resulting in a widely spaced, externally rotated symphysis pubis. In boys, the penis appears foreshortened and wider, with dorsal curvature with an open urethral plate. In girls, the mons and clitoris are bifid, and the entire urethra is open dor-sally. In both sexes, the reproductive organs are normal. Indirect hernias are common. The abnormal anatomy of the puborectalis muscle can result in rectal prolapse. The upper urinary tracts are usually normal; however, anomalies of renal development and fusion can occur. Bilateral vesicoureteral reflux (VUR) is almost universal.

MANAGEMENT

MANAGEMENT

The goals of management of the exstrophy-epispadias complex include closure of the bony pelvis (with or without osteotomies), closure of the bladder plate, reconstruction of the urethra, closure of the abdominal wall defect, preservation of renal function, and creation of a functionally and cosmetically acceptable penis in boys, and mons and clitoris in girls. The surgical management is usually staged, with closure of the bladder performed in the first 72 hours, but a one-stage technique, including bladder closure concomitant with epispadias repair, can also be performed. Epispadias reconstruction and penile lengthening are usually accomplished at 1 year of age if the staged approach is chosen. The final stage of surgical reconstruction involves bladder neck reconstruction for age-appropriate urinary incontinence and ureteral reimplantation to correct vesicoureteral reflux, which is performed at approximately 4 to 5 years of age, or when there is adequate bladder capacity. Some groups have shown encouraging results with reconstruction of the epispadiac penis and closure of the bladder in a single stage. Despite successful bladder closure and epispadias repair, some bladders fail to grow. In these cases, bladder augmentation with a bowel segment and clean intermittent catheterization are required. With a staged approach, success rates for spontaneous voiding with urinary continence approach 75% to 85%. As the complete primary repair of bladder exstrophy is still a relatively recent technique, data on long-term follow-up for continence are still accruing for these children.

ANTERIOR URETHRAL ANOMALIES

URETHRORRHAGIA

URETHRORRHAGIA

Urethrorrhagia occurs only in boys and consists of terminal hematuria or spotting of blood on the underwear. It is often associated with mild dysuria. Diagnosis is made by history and confirmed with a normal physical examination. The urinalysis may show microscopic hematuria but is often negative. Evaluation should include an ultrasound of the kidneys and bladder to exclude any structural anomalies if hematuria occurs. Cystoscopy is rarely indicated unless the symptoms persist beyond 6 months or the history is inconsistent with the diagnosis. The symptoms are usually intermittent and may last for up to 1 year or longer, but more than 90% resolve by 2 years.14 Although this condition causes great concern and anxiety in parents, the process is self-limited, and reassurance and patience is the preferred approach.

URETHRAL PROLAPSE

URETHRAL PROLAPSE

Complete eversion of the urethral mucosa through the external meatus or urethral prolapse occurs almost exclusively in prepubertal girls of African descent. The etiology of the prolapse is unclear but may be related to an intrinsic anatomic defect involving the periurethral smooth muscle layers in association with episodic increases in intra-abdominal pressure. Predisposing factors include coughing, constipation, trauma, and urinary and vaginal infections. Presenting symptoms include vaginal bleeding or spotting on the child’s underwear and sometimes mild dysuria.15 Physical examination often demonstrates a typical-appearing everted, hemorrhagic, donut-shaped periurethral mass. A prolapsed ureterocele or a vaginal rhabdomyosarcoma must also be included in the differential diagnosis due to similar presentation. Often, this entity is misdiagnosed, and concern for sexual abuse is raised. Management includes conservative medical treatment with reduction of the prolapse, sitz baths, and topical antibiotics. Surgical resection of the prolapsed portion of the urethra may be required after the acute inflammation has resolved.

ANOMALIES OF THE PENIS, TESTIS, AND SCROTUM

The development of the male reproductive organs is discussed in Chapters 64 and 538.

HYPOSPADIAS

Hypospadias is a congenital abnormality of the penis in which underdevelopment of the anterior urethra results in an ectopic ventrally located urethral meatus. Hypospadias is the most common congenital abnormality of the penis, occurring in 1 in every 300 male children, and it more common in infants of Jewish and Italian descent.

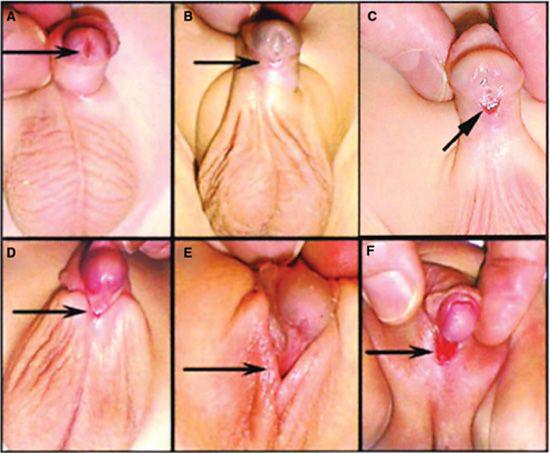

Hypospadias is classified depending on the location of the urethral opening along the penile shaft (Fig. 476-2).16 Anterior hypospadias is described as glandular (on the inferior surfaces of the glans), coronal (in the balanopenile furrow), or distal (in the distal third of the penile shaft). In middle hypospadias, the opening is in the middle third of the penile shaft. Posterior hypospadias has an opening from the perineum to the proximal third of the penile shaft. Chordee or penile curvature refers to the downward curvature of the penis that typically accompanies the more severe forms of hypospadias. Standard classification of hypospadias does not take into account the associated penile curvature. A patient with severe curvature and an anterior urethral meatus may in fact require a more extensive surgery to correct both the curvature and the abnormal urethra.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

The cellular migration that leads to closure of the urethral groove is caused by testosterone, with full enclosure of the penile urethra by the second trimester of pregnancy. Hypospadias may be due to genetic, endocrinologic, or environmental factors. There is also a 20% chance that an infant born with hypospadias has a family member with the condition. It is more common in twins compared to a single birth. Maternal exposure to increased levels of progesterone, common during in vitro fertilization (IVF), increases the risk for hypospadias in the infant. Environmental exposure to estrogen during urethral development may also be a risk factor; specifically, environmental chemicals that act as antiandrogens and interfere directly with the action of testosterone-related gene expression.17

DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

The diagnosis of all but minor forms of hypospadias is easily made on physical examination of newborn boys (Fig. 476-2). The characteristic dorsal hooded foreskin leads to the diagnosis of hypospadias in most cases. Unilateral and especially bilateral nonpalpable cryptorchidism associated with hypospadias should be considered one of possible presentations of disorders of sexual differentiation, and appropriate evaluation should be performed (see Chapter 539). Routine imaging of the upper urinary tract is unnecessary because abnormalities are uncommon in children with isolated hypospadias. In severe cases of hypospadias, a well-formed prostatic utricle may be present that usually causes no complications, except for occasional urinary tract infections and difficulty with catheter passage.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree