Urinary Tract Infections

Keith M. Krasinski

Identification and treatment of urinary tract infections (UTIs) is important not only for explaining and managing signs and symptoms such as fever and dysuria but also for preventing pyelonephritis and sepsis and long-term complications including hypertension, chronic renal disease, and renal failure. Recurrent UTI is often a herald for anatomic and functional abnormalities that are associated with chronic renal disease.1,2

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

Bacteriuria occurs in 0.1% to more than 1% of infants.3,4 Urinary tract infection (UTI) is more common in males, however, circumcision to prevent UTI is not warranted. Premature infants have 2 to 3 times this rate of UTI. During preschool years, UTI is more common in girls (4.5%) than in boys (0.5%) with long-term surveillance studies of school children revealing persistent bacteriuria in 1.2% of girls and in 0.4% of boys. Each year an additional 0.4% of girls develop bacteriuria.5 White girls have more frequent reinfections than black girls. The incidence of UTI in females of high school and college age is approximately 2%.

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND GENETICS

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY AND GENETICS

Gram-negative bacterial pathogens causing urinary tract infection (UTI) include Escherichia coli that are responsible for more than 80% of infections; Klebsiella pneumoniae, Proteus mirabilis, Enterobacter aerogenes, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, and Serratia marcescens that are more likely to be associated with recurrent or chronic infections; and Salmonella species, Haemophilus influenzae, and Gardnerella vaginalis. Gram-positive bacteria causing UTIs include Staphylococcus aureus and coagulase negative Staphylococci that cause infections in infants and sexually active females. Enterococcus species, and Streptococcus pneumoniae are also responsible for UTIs.

Adenovirus types 11 and 21 and the human papovavirus BK have been reported as causes of acute hemorrhagic cystitis.11-14 Symptomatic and asymptomatic BK viruria is associated with bone marrow transplantation. Fungi such as Candida albicans may be responsible for UTIs (1) in patients with indwelling catheters during the course of their treatment with antibiotics; (2) in patients immunocompromised as a result of disease, steroids, or cytotoxic chemotherapy; and (3) as a result of renal seeding during fungemia.

The ascending route is the most common pathway of UTI. Bacteria that colonize the perineum and distal urethra may eventually spread to the bladder. Massage of the urethra, such as occurs during masturbation and sexual intercourse, forces bacteria into the bladder.15,16 Hematogenous spread may occur during the course of neonatal sepsis; however, even in infants, ascending infection leading to bacteremia is more common.

Microbial Virulence Factors

A number of virulence factors of microorganisms are associated with UTIs, including size of inoculum, the presence of pili or fimbriae effecting mucosal cell adherence (mannose-sensitive type 1, common, P pili, X pili), surface antigens, motility, and urease production. Certain organisms are particularly virulent or adapted for the urinary tract.19,20

E coli O antigens are cell-wall lipopolysaccharides that are immunogenic and induce local and systemic antibody responses in patients with pyelonephritis. Of the 150 or more E coli O serogroups, only a few (01, 02, 04, 06, 07, 075) are responsible for most UTIs. These O serogroups possess large quantities of K antigen, of which types 11, 24, 36, and 37 account for the majority of isolates from children with pyelonephritis.21,22 The O antigens associated with pyelonephritis appear to confer the ability to resist agglutination and bactericidal effects of serum, unlike the O serotypes of organisms causing cystitis.22-24E coli with P pili have their favored site of attachment on the uroepithelium of the kidneys, where receptors are distributed with greatest density.28,29 UTIs are more likely to occur in individuals who express the P blood group antigen.37 Other factors that impact upon bacterial virulence include variations in the bacteria’s motility38 and urease production.39

Host Defense Factors

The known host defense mechanisms of the urinary tract include flushing mechanisms of the bladder, antibacterial activity of urine (decoy effect of oligosaccharides), prostatic secretions of postpubescent males, low vaginal pH and estrogen in females, antiadherence effects of uromucoid and mucopolysaccharide, humoral immunity, local secretory immunity, IgA, lack of P blood group antigen, and the protective effect of host normal flora. These are discussed in more detail in electronic text.

There are also sex-specific contributions to host defense.42-47 The shorter female urethra, as compared to the male urethra, may explain the disproportionately higher female predilection for UTI. Glucose improves urine as a culture medium and inhibits the migrating, adhering, aggregating, and killing functions of polymorphonuclear leukocytes. Thus, uncontrolled diabetics are at increased risk of UTIs.

The role of the host’s normal perineal flora of lactobacilli, Staphylococcus epidermidis, coryne-bacteria, streptococci, and anaerobes in preventing colonization with uropathogens is not completely understood; however, disturbing the local ecology with (systemic) antibiotics is associated with infection.

Predisposing Factors

Factors predisposing the host to UTI include obstruction, stasis, reflux, pregnancy, sexual intercourse (in females), hyperosmolality of renal medulla, host cell receptor sites for attachment, immunologic cross-reactivity of bacterial antigen and human protein, chronic prostatitis, B or AB blood type, other genetic predispositions, and immunodeficiency. Sexual intercourse in females produces transient bacteriuria and is associated with an increased risk of UTI. Eighty percent of UTIs begin within 24 hours of intercourse in sexually active women.70,71 Adult males with chronic prostatitis are at risk for recurrent UTIs because of intermittent seeding of their urinary bladders. Other factors such as chronic perineal irritation from soap, bubble bath, or pinworms and trauma such as occurs by bike and horseback riding and, in older boys, self-instrumentation also contribute. Factors that are particularly relevant to hospitalized individuals and those with chronic conditions include urinary tract instrumentation, especially from urinary catheters and exposure to antimicrobial agents.

The single most important host factor is urinary stasis resulting from obstruction of urinary flow or bladder dysfunction. Obstruction is more frequently observed in the younger patient and should prompt timely imaging of the urinary system. The most common causes of stasis include congenital anomalies of the ureter or urethra (valves, stenosis, bands), calculi, dysfunctional or incomplete voiding, extrinsic ureteral or bladder compression, and neurogenic bladder (functional obstruction).

Children with vesicoureteral reflux often develop upper UTIs and renal scarring. Reflux can be detected in 30% to 50% of children with symptomatic or asymptomatic bacteriuria.68 Additionally, kidneys scarred in association with reflux are more susceptible to reinfection.

A genetic predisposition to urinary tract is suggested by the association of blood group P antigen and specific Toll-like receptor (TLR-2) polymorphisms with an increased incidence of UTIs.

CLINICAL FEATURES

CLINICAL FEATURES

The clinical manifestations of urinary tract infections (UTIs) depend on the age of the patient as well as the anatomic location and severity of the infection. Symptoms in newborn infants are nonspecific and include lethargy, irritability, poor feeding, vomiting, diarrhea, apnea, fever or hypothermia, or prolonged jaundice and suggest systemic infection. Symptoms in those less than 2 years of age are also characteristically nonspecific, such as fever, and some appear to be related to the gastrointestinal tract rather than the urinary tract: failure to thrive, feeding problems, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal distention, and late-onset jaundice. Infants and children may have signs of balanitis, prostatitis, and orchitis or overt manifestations of sepsis. UTIs in children more than 2 to 3 years of age are often characterized by fever, frequency, and dysuria. The signs of cystitis may also result from other causes of urethral irritation in children, such as bubble bath, vaginitis, pinworms, masturbation, or sexual abuse. Abdominal pain, flank pain, and hematuria may be present. The occurrence of enuresis in a child who has been toilet trained could also be a manifestation of a UTI. Young infants and boys may have an obstructive uropathy characterized by dribbling of urine, straining with urination, or a decrease in the force and size of the urinary stream. These findings of obstruction can be aggravated by infection. Other history should include infrequent voiding, incomplete voiding, and a weak urinary stream.

The manifestations of UTIs in adolescents are similar to those in adults, including frequency, urgency, dysuria, and painful urination of a small amount of turbid urine that occasionally may be grossly bloody. Fever is usually absent. The differential diagnosis of cystitis includes vaginitis, urethritis, and chemically induced irritation from female hygiene products. Upper UTI may be characterized by fever, chills, and flank pain or abdominal pain. Upper and lower tract infections may coexist. The presence of costovertebral angle tenderness on examination directs attention to the upper tract; however, its absence does not exclude pyelonephritis. The clinical manifestations in some patients may be so atypical that they resemble gallbladder disease or acute appendicitis.

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

DIAGNOSTIC EVALUATION

Physical examination should include measurement of blood pressure because hypertension may be caused by chronic renal failure. Abdominal examination may reveal a mass, tenderness, or organomegaly. Genital examination should be conducted to investigate vaginitis and labial adhesions in girls; phimosis in boys; and evidence of irritation, sexual activity, or sexual abuse. Rectal examination allows assessment for lax sphincter tone, which may be associated with neurogenic bladder. Similarly, examination of the back may reveal a dimple or other defect associated with neurogenic bladder as a result of spinal cord involvement.

Laboratory examination begins with evaluation of urine. Normal urine is a sterile, acellular, glomerular filtrate influenced by tubular secretion and absorption. Sustained absence of inflammatory responses on repeat urine analysis constitutes strong evidence of absence of infection.87 The diagnosis of urinary tract infection (UTI) is suggested by the detection of white blood cells (WBCs) and bacteria in the urine. Confirmation requires quantitative culture of uncontaminated and properly processed urine. Asymptomatic bacteriuria is defined as significant bacteriuria in a patient who has no clinical evidence of infection. Overdiagnosis of UTIs carries the risks of unnecessary treatment, diagnostic workup, and their attendant visits and costs. Underdiagnosis carries the risks of continued symptoms, sepsis, and chronic progressive renal disease.

Laboratory Tests

Laboratory testing for UTI is best performed using a standardized approach. Five mL of urine is centrifuged at 3000 rpm for 3 minutes, followed by resuspension of the sediment. The occurrence of more than 20 white blood cells per high-power field usually correlates with significant bacteriuria of 100,000 colonies in a clean-catch sample. However, pyuria does not necessarily indicate the presence of a UTI. Patients of all ages with or without pyuria may or may not have an infection. Unfortunately, false-positive results as high as 30% occur and may be caused by vaginal washout, chemical irritation, fever, viral infection, immunization, or glomerulonephritis. It is likely that most patients with symptomatic UTIs will have pyuria.

Microscopic examination of urine for bacteria is also useful. The presence of 1 bacterium per oil-immersion field on a Gram-stained preparation form a midstream clean-catch urine specimen, is equivalent to approximately 100,000 bacteria per milliliter urine. Ten to 100 bacteria per high-power field on a centrifuged sediment correlates with significant bacteriuria. The sensitivity of urine analysis is 82%, with a specificity of 92% for detection of UTI. Urine analysis does not perform as well in younger infants.88,89

Dipstick chemical tests most commonly employed include tests for nitrite and leukocyte esterease. Nitrite detection in urine is based on the observation that many urinary pathogens convert nitrate to nitrite in the bladder. The nitrite strip for detection of UTI uncommonly yields false-positive results. False-negative results are more common (25–30%) as a result of inadequate dietary nitrates, diuresis, an inadequate time for bacterial proliferation, or infections caused by nitrite negative organisms, including Staphylococcus saprophyticus, Acinetobacter species, enterococci, and pseudomonads. The test is best used on concentrated or first-morning samples and may have an important role for outpatient and home monitoring following diagnosis and treatment of a UTI.90 Leukocyte esterase testing detects enzymes generated by inflammatory cells. This test is neither more sensitive nor more specific than the detection of the cells themselves, but it may be easier to perform in some clinical settings. As with pyuria, a positive test does not establish the diagnosis of UTI.

Urine Culture

Culture of carefully collected fresh urine (less than 30 minutes old, refrigerated or held on ice), minimizing the likelihood of contamination, is the cornerstone of diagnosis of UTI. Quantitative culture of urine is the standard for diagnosis. Because UTIs, particularly those in infants and young children, have nonspecific presentations, invasive methods for valid urine collection for culture are often required. Urine for culture may be obtained (1) as a midstream clean-catch specimen in adults, adolescents, and older children; (2) by catheterization; or (3) by suprapubic aspiration in young children and infants. The performance characteristics of the previously discussed diagnostic tests are summarized in eTable 238.1  . Suprapubic aspiration is least likely to be contaminated. Strait catheterization follows gentle cleansing of the anterior urethra with soap and water. Because the urethra cannot be sterilized, the first aliquot of urine that flows should be discarded to avoid collecting bacteria that have been pushed into the bladder. A later aliquot should be sent for culture.91 A midstream clean-catch urine collection should be preceded by disinfection of the area about the urethral meatus, then rinsed clean prior to urination. Girls can straddle the toilet seat to minimize contamination by urethral-vaginal reflux. Collections in younger children should be supervised by a professional. Random urine samples and urine collected as bag specimens should not be used as a basis for the diagnosis of UTI. Screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria is not usually indicated.

. Suprapubic aspiration is least likely to be contaminated. Strait catheterization follows gentle cleansing of the anterior urethra with soap and water. Because the urethra cannot be sterilized, the first aliquot of urine that flows should be discarded to avoid collecting bacteria that have been pushed into the bladder. A later aliquot should be sent for culture.91 A midstream clean-catch urine collection should be preceded by disinfection of the area about the urethral meatus, then rinsed clean prior to urination. Girls can straddle the toilet seat to minimize contamination by urethral-vaginal reflux. Collections in younger children should be supervised by a professional. Random urine samples and urine collected as bag specimens should not be used as a basis for the diagnosis of UTI. Screening for asymptomatic bacteriuria is not usually indicated.

The likelihood of UTI as detected by culture is a function of the epidemiologic setting, the method of collection, and the prior probability of infection. Organisms in any number are considered significant when obtained by suprapubic aspiration. When urine is collected by catheterization, a colony count greater than 1000 per milliliter of urine is usually considered diagnostic. However, for infants, counts of 10,000 colony-forming units (cfu)/mL or greater have been obtained from catheterized specimens in the absence of other findings of UTI.92 Infections should be defined by a colony count greater than 50,000 cfu/mL and pyuria of at least 10 leukocytes/mm3 in samples collected by straight catheterization of children.89 If the quantitative culture from a midstream sample reveals 100,000 bacteria or more per milliliter of urine, it also indicates the presence of significant bacteriuria. In males, greater than 10,000 bacteria per milliliter suggests infection, but is equivocal in females and thus should be repeated if symptoms have persisted. A count of less than 10,000 bacteria per milliliter suggests probable contamination. The specificity of this technique is enhanced from 80% to 95% if significant bacteriuria is demonstrated on repeat testing.93 In the presence of pyuria and symptoms, a single culture indicating significant bacteriuria is considered diagnostic in adolescents and adults. The specific bacterium recovered by culture should be identified as a guide to appropriate therapy.

Localization of Infection

Localization of the anatomical site of infection remains difficult. Although pyelonephritis is classically associated with fever, flank pain or tenderness, decreased renal concentrating ability, and an elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate, the absence of these findings does not reliably exclude upper tract disease.

The use of sensitive technetium (Tc-99m), dimercaptosuccinic acid (DMSA), or glucoheptonate scanning is gaining favor in the early diagnosis of upper UTIs,95 as it appears to be more sensitive than other easily available methods of localization.95-97 In experimental studies, the sensitivity and specificity of scanning were 91% and 99%, respectively, with overall 97% agreement with histopathologic findings, although there may be substantial interobserver variability in the detection and classification of renal cortical defects.96,98

The detection of antibody coating of bacteria is a sensitive, reliable, noninvasive indicator of renal bacteriuria in adults.99,100 Unfortunately, when this immunofluorescence technique was applied to children with bacteriuria, it was neither sensitive nor specific.101,102 Elevations of urinary lactic dehydrogenase greater than 150 units/L and elevations of fractions 4 and 5, C-reactive protein (CRP; > 30 μg/mL) and increased urinary IL-1-β are markers for pyelonephritis.105

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Clinical findings in infants can be due to a wide range of other infectious and noninfectious processes. In older children and adults, various conditions that may simulate cystitis or pyelonephritis should be considered, including urinary calculi, dysfunctional elimination and diabetes, vaginal foreign body nonspecific vulvovaginitis gonorrheal or chlamydial urethritis may simulate urinary tract infection. A right-sided pyelonephritis could be confused with acute appendicitis, gallbladder disease, or hepatitis.

RADIOLOGIC EVALUATION

RADIOLOGIC EVALUATION

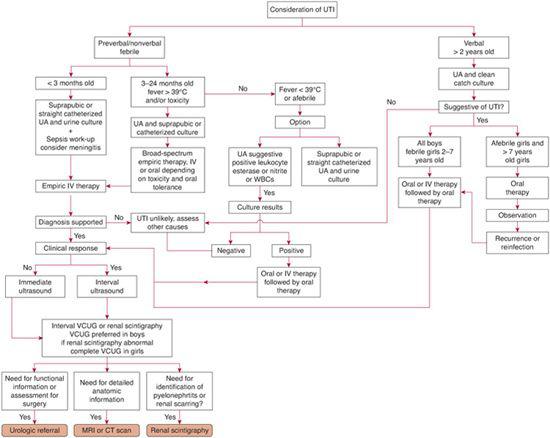

Imaging strategies are addressed in Figure 238-1. Radiologic evaluation for anatomic abnormalities is indicated in all infants, children, and adolescents except in girls > 2 years of age. In girls > 2 years of age, imaging is indicated in the presence of symptomatic infection, physical examination findings suggestive of possible renal or collecting system abnormalities, abnormal voiding, hypertension, or poor physical development.110 Clinical factors associated with an increased likelihood of finding an anatomic abnormality include recurrent infection, poor urinary stream, palpable kidneys, unusual organisms, invasive infection, prolonged clinical course, failure to respond to antibiotics in 2 to 3 days, and patients with unexpected demographics such as older boys.111 If radiographic studies are not performed in older girls after the primary infection, they are indicated if there is a recurrence. Acute imaging is indicated in children who do not have the expected clinical response to therapy in order to investigate the role of obstruction. Ultrasonography should be performed acutely for disease that is complicated or fails to resolve promptly. Routine radiologic studies need only be delayed until infection and the resultant bladder irritability is resolved.

Information obtained by imaging may or may not alter acute management, but the information has implications for long-term management. In uncomplicated, rapidly resolving disease, the results of renal ultrasound and dimercaptosuccinic acid scan at the time of acute infection have not modified management, suggesting that selective performance of ultrasound, interval voiding cystourethrogram at 1 month, and dimercaptosuccinic acid scan at 6 months may be more useful to identify vesicoureteral reflux and scarring.

Vesiculoureteral reflux is the most commonly occuring abnormality. Voiding cystourethrogram (VCUG) better characterizes reflux and can demonstrate bladder and urethral abnormalities. Voiding cystourethro-gram is preferred in boys and in girls with evidence of voiding dysfunction while uninfected. Radionuclide cystography has the advantage of less radiation exposure and is the preferred method for following the degree of reflux in those previously diagnosed. Radio-nuclide cystography may be most useful in older children in whom reflux is considered unlikely.114 One of the confounding issues with renal scintigraphy is whether an abnormal area represents an area of scarring due to vesicoureteral reflux–associated pyelonephritis or a congenital renal lesion with hypoplasia or dysplasia and associated urinary tract infection without secondary renal damage is unknown.115

Children with no reflux or grade I reflux require only follow-up examination. Children with grade II or III reflux may be candidates for suppressive therapy. If grade III or IV reflux is detected, it probably will be persistent and not be the result of acute infection. Children with grade IV reflux are also candidates for suppressive therapy and urologic consultation.

Radionuclide scanning appears to have increased sensitivity in detecting renal scars following acute pyelonephritis. Approximately two thirds of abnormalities demonstrated acutely resolve over time.98,121 New scarring occurs at sites corresponding to the localization of acute inflammation and appears to be unrelated to vesicoureteral reflux.122

When detailed anatomic information is required, computed tomography or magnetic resonance imaging should be performed.

Urologic referrals are appropriate for patients with obstruction, urethral valves, renal scarring, anatomic abnormalities, and dysfunctional voiding; however, there is no strong evidence to link medical or surgical interventions for vesicoureteral reflux with improved long-term outcome.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

The objectives of treatment of children with urinary tract infections (UTIs) are fivefold: (1) to eliminate the infection, (2) to detect and correct functional or anatomic abnormalities, (3) to prevent recurrences, (4) to preserve renal function, and (5) prevent late sequelae such as hypertension.

Antimicrobial therapy is a mainstay of intervention. Suggested treatment regimens for patients with UTI are shown in Table 238-2. Parenteral administration of antibiotics is appropriate in patients who are toxic, dehydrated, or incapable of accepting or retaining oral intake, or when compliance is not assured. Newborn infants with UTIs and children suspected of having pyelonephritis should be treated empirically at the time of diagnosis because of the frequency of associated bacteremia. Empiric therapy for newborn infants with urinary tract infection and suspected sepsis should include cefotaxime (100 mg/kg/day divided q 12 hours for infants < 1 week of age and 150 mg/kg/day divided q 8 hours for infants > 1 week of age) and ampicillin (100 to 200 mg/kg/day). Alternatively, cefotaxime alone is satisfactory for treatment of susceptible enteric Gram-negative bacillary UTI.

Older children with mild symptoms and those with lower UTIs may not require antimicrobial therapy until the results of urine culture are available. If therapy is indicated before the results of culture become available, oral cefixime is suggested because E coli and other Gram-negative bacilli are the most common pathogens. Older children and young adults may be treated with ciprofloxacin, which is labeled for use down to 1 year of age, or another fluoroquinolone.

Older children with suspected pyelonephritis can be treated empirically with ceftriaxone 50 to 75 mg/kg/day intravenously or intramuscularly, possibly with the addition of an aminoglycoside. Recent data indicate that orally administered cephalosporin drugs with activity against Gram-negative rods are as effective in the time to defeverescence (approximately 25 hours), ability to eradicate the organism from the urine, prevention of recurrences, and prevention of renal scarring at 6 months135 as parenterally administered agents.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree