Fig. 11.1

Clinical photograph showing left undescended testes

In 90 % of cases, an undescended testis can be palpable in the inguinal canal ; in a minority, the testis or testes (impalpable) are in the abdomen or nonexistent.

Undescended testes are associated with:

Reduced fertility.

Increased risk of testicular germ cell tumors .

Psychological problems at the time of puberty.

Undescended testes are more susceptible to testicular torsion and infarction.

Undescended testes are associated with inguinal hernias.

To reduce these risks, undescended testes are usually brought into the scrotum in infancy.

Ascent of testes :

Although cryptorchidism nearly always refers to congenital absence or maldescent, a testis observed in the scrotum in early infancy can occasionally “reascend” into the inguinal canal .

Retractile testis :

A testis which can readily move or be moved between the scrotum and the inguinal canal is referred to as retractile testis. Retractile testes are more common than truly undescended testes and do not need to be operated on.

Embryology

Embryologically, the testes develop from primordial germ cells to form testicular cords along the genital ridge in the abdomen of the embryo. This is under the influence of the SRY gene on the short arm of the Y chromosome which influences the developing gonad (indifferent gonad) to become a testis rather than an ovary by the 2nd month of gestation.

The cells in the testes differentiate into Leydig cells (testosterone-producing cells) and Sertoli cells (müllerian-inhibiting hormone-producing cells). This occurs during the 3rd to 5th months of intrauterine life. The germ cells become fetal spermatogonia.

Male external genitalia develop during the 3rd and 4th months of gestation.

The testes remain high in the abdomen until the 7th month of gestation, when they move from the abdomen through the inguinal canals and into the scrotum.

It has been proposed that the movement of the testes from the abdomen into the scrotum occurs in two phases.

The first phase: movement of the testes across the abdomen to the entrance of the inguinal canal. This is influenced by anti-müllerian hormone (AMH) .

The second phase: movement of the testes through the inguinal canal into the scrotum. This is influenced by androgens (most importantly testosterone).

In rodents, it has been shown that androgens induce the genitofemoral nerve to release calcitonin gene-related peptide (CGRP) , which produces rhythmic contractions of the gubernaculum. This is a ligament which connects the testis to the scrotum and helps in its descend into the scrotum but a similar mechanism has not been demonstrated in humans.

Maldevelopment of the gubernaculum or deficiency or insensitivity to either AMH or androgen therefore can prevent the testes from descending into the scrotum.

In many infants with inguinal testes, further descent of the testes into the scrotum occurs in the first 6 months of life. This is attributed to the postnatal surge of gonadotropins and testosterone that normally occurs between the 1st and 4th months of life.

Spermatogenesis continues after birth till about 5 years of age. Some of the fetal spermatogonia become type A spermatogonia and more gradually, other fetal spermatogonia become type B spermatogonia and primary spermatocytes. Spermatogenesis arrests at this stage until puberty.

Most normal-appearing undescended testes are also normal by microscopic examination but reduced spermatogonia can be found. The tissues in undescended testes however start to degenerate and become abnormal microscopically between 2 and 4 years of age. There is some evidence that early orchidopexy reduces this degeneration.

A testis that is absent from the normal position in the scrotum can be:

1.

Undescended (impalpable) and found anywhere along the “path of descent” from high posteriorly in the retroperitoneal space, just below the kidney, to the inguinal ring

2.

Undescended (palpable) and found in the inguinal canal

3.

Ectopic found away from the normal path of descent, usually outside the inguinal canal, and sometimes even under the skin of the thigh, the perineum, the opposite scrotum, or the femoral canal

4.

Undeveloped (hypoplastic) or severely abnormal (dysgenetic; Fig. 11.2)

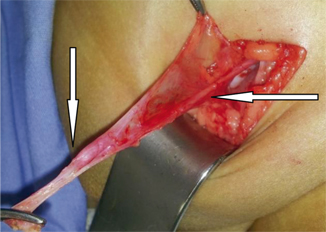

Fig. 11.2

Intraoperative photograph showing atrophic testes. Note the vas deferens and the small atrophic testes, indicated by arrows

5.

Vanished (anorchia)

Etiology

In most full-term infant boys with cryptorchidism, a cause cannot be found.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree