Tumors

B. Stephens Richards

SOLITARY OSTEOCHONDROMA

Osteochondroma, a cartilage-capped bony projection protruding from the surface of a bone, is the most common benign bone tumor. It reportedly accounts for 36% to 41% of all bone tumors.1 More than 50% of solitary osteochondromas occur in the metaphyseal area of the knee (distal femur and proximal tibia) and shoulder (proximal humerus) (Fig. 219-1).

The tumor often resembles a cauliflower. The surface usually is lobular, with multiple bluish-gray cartilaginous caps covering the irregular bony mass. The cartilaginous cap is usually 1 to 3 mm thick, but in the younger patient it may be noticeably thicker.

In the majority of patients, the osteochondroma becomes evident between the ages of 10 and 20 years, with a slight male preponderance. An osteochondroma may be discovered as an incidental radiographic finding, or it may be detected by the patient who feels a protruding bump. Other factors that often draw attention to the osteochondroma include localized pain, growth disturbance, limited joint motion, or abnormal cosmetic appearance.

On the radiograph, the cortex and cancellous bone of the osteochondroma blend with the cortex and cancellous bone of the normal bone.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

Because a solitary osteochondroma is a benign tumor, it does not need to be surgically excised if it is asymptomatic. Excision usually is reserved for those lesions that cause pain or symptomatic impingement on neurovascular structures or that interfere with joint function. Pain usually becomes an issue when an osteochondroma is repeatedly bumped on its prominence. Sometimes the osteochondroma is considered cosmetically unacceptable and the adolescent will ask to have it removed, preferring a scar to a bump. The prognosis following excision of a chondrosarcoma is excellent.

HEREDITARY MULTIPLE EXOSTOSES

Hereditary multiple exostoses, or multiple osteochondromatosis, is considered an autosomal dominant condition affecting numerous areas of the skeleton that have been preformed in cartilage. The median age at the time of diagnosis is approximately 3 years. Hereditary multiple exostoses has a penetrance of 50% by age 3 years. By 12 years of age, nearly all affected individuals have evidence of exostoses, as penetrance of the disorder has been found to reach 96% to 100%.2,3

Numerous genetic studies have found anomalies on chromosomes 8, 11, and 19, making this a genetically heterogenous disorder.4-6 Specifically, the three loci include 8q24.1 (EXT1), 11p11–12 (EXT2), and 19p (EXT3). These genes are deleted in exostoses-derived tumors, supporting the hypothesis that they encode tumor suppressors.

The gross pathologic and microscopic features of hereditary multiple exostoses are similar to those described for solitary osteochondromas. Numerous sites can be involved. On presentation, 5 or 6 exostoses typically may be found, involving both the upper and lower extremities.

FIGURE 219-1. A: Solitary osteochondroma involving the distal left femur. B: Clinical photograph in the operating room showing the resected specimen.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

The only treatment for hereditary multiple exostoses is surgery. However, the mere presence of an osteochondroma is not an indication for surgery. Reasonable indications include (1) pain from external trauma or irritation of surrounding soft tissues; (2) growth disturbance leading to angular deformity or limb length discrepancy; (3) joint motion compromised by juxta-articular lesions; (4) soft tissue (tendon, nerve, or vessel) impingement or tethering; (5) spinal cord compression; (6) false aneurysm produced by an osteochondroma; (7) painful bursa formation; (8) obvious cosmetic deformity; and (9) a rapid increase in the size of a lesion. Life expectancy is average unless malignant degeneration of an osteochondroma has occurred and metastases have developed.

Transformation of a lesion in hereditary multiple exostoses to chondrosarcoma during childhood is exceedingly rare.7 In general, transformation in adulthood remains uncommon, with current reports indicating the risk to be 0.9% to 5%.2,6,8,9 The most frequent sign of sarcomatous change is a painful, enlarging mass, usually one of long duration.10

NONOSSIFYING FIBROMA AND FIBROUS CORTICAL DEFECT

Fibrous defects in bone are common lesions in childhood. They are found in the metaphyseal regions of the long bones, particularly the femur and the tibia. These lesions contain fibrous tissue, thus leading to the terms fibrous cortical defect and nonossifying fibroma. These fibrous lesions appear to be developmental defects due to a localized disturbance of bone growth and may not be representative of true neoplasms. Most are asymptomatic, picked up as an incidental finding during radiographs taken for other reasons, and eventually resolve during remodeling at the metaphyseal (growing) end of the bone.

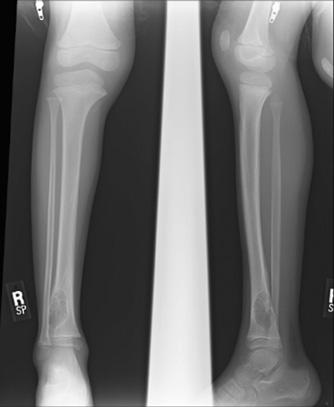

On radiographs, these lesions are sharply delineated, radiolucent, multiloculated, eccentric, and outlined by a sclerotic border (Fig. 219-2).11 These findings are usually so characteristic that further radiologic studies are unnecessary.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

Fibrous cortical defects do not require treatment because they usually regress over time. Larger, nonossifying fibromas can be monitored without surgical intervention, and if fractures do occur, they can be successfully managed nonoperatively.12 Occasionally, discomfort or repeated fractures may require intralesional excision by curettage down to normal bone, with the defect filled with bone graft.

SIMPLE BONE CYSTS (SOLITARY BONE CYST, UNICAMERAL BONE CYST)

Simple bone cysts represent approximately 3% of all biopsied primary bone tumors and nearly always occur during the first 2 decades of life, most often between 4 and 10 years of age.13 The majority of cysts occur in the metaphyseal region of the proximal humerus or femur, with approximately 50% of cases involving the humerus and 18% to 27% affecting the femur. Its cause remains uncertain.

Cysts can be asymptomatic and may be discovered incidentally when radiographs are obtained for other reasons. More often, though, the cysts are diagnosed because of pain. The pain may be mild and reflective of a microscopic pathologic fracture. More abrupt discomfort occurs when a pathologic fracture occurs following relatively minor trauma, such as a fall. These fractures occur in up to 90% of patients and heal readily, though the cysts do not.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree