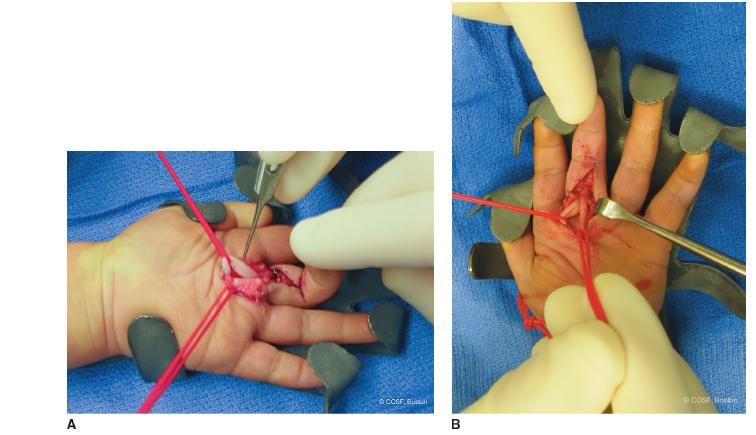

FIGURE 12-1 Surgical technique of trigger thumb release. A: Clinical photograph of a pediatric trigger thumb. B: Prior to surgical release, marks are made on either side of the palpable Notta nodule in the MCP flexion crease, marking the extent of the transverse skin incision. C: After spreading and retraction of the soft tissues and neurovascular bundles, the tendon sheath is exposed. D: The A1 pulley is incised. Note the IP joint hyperextension following pulley release. E: A bulky soft dressing is applied after wound closure.

Clinical Evaluation

Patients with trigger thumbs typically present during the first 18 months to 3 years of life with either triggering or a fixed flexion contracture of the IP joint. Often the abnormality is noted incidentally by family, teachers, or other medical care providers. There are times when it is recognized with some sort of trauma; then, it can be mistaken by parents, primary and emergency room physicians, and caregivers as an acute dislocation. They can be further mislead by a flexed posture on the lateral radiograph with unossified epiphysis of the distal phalanx; the sense of “joint reduction” with manipulation of the nodule distal to the first annular (A1) pulley; and frustration of almost immediate recurrent “dislocation” in their postreduction splint. When locked, the thumbs are not painful, nor do patients inhibit spontaneous use of the thumb and hand. When spontaneously or manually reducible, abrupt extension of the thumb IP joint may be associated with transient pain, which may alert the family to the condition. One-third of patients will demonstrate bilateral thumb involvement, though this may be metachronous with variable severity.18 Careful inspection and palpation will identify the Notta nodule within the FPL tendon, which will demonstrate excursion with passive IP joint motion. Often in long-standing cases, the MCP will demonstrate compensatory hyperextension laxity or instability, as the child attempts to open the first web space during cylindrical grasp. Nodules and triggering are not seen in the index through small fingers in the typical trigger thumb.

In trigger fingers, there too will be characteristic triggering or less commonly fixed flexion contractures, typically at the proximal interphalangeal (PIP) joint and associated with what feels like a Notta nodule (Figure 12-2). Both single and multiple digital involvements occur commonly, and bilateral hand involvement is not uncommon. Care should be made to identify associated medical conditions; in cases of associated mucopolysaccharidoses, evaluation for carpal tunnel syndrome and/or median neuropathy should be performed.19

Natural History

Say you were standing with one foot in the oven and one foot in an ice bucket. According to the percentage people, you should be perfectly comfortable.

—Bobby Bragan

Definitive statements about the natural history of pediatric trigger thumbs cannot be made. Most information comes from retrospective case series, with inherent biases and inadvertent interventions in the course of “clinical observation.” The “spontaneous resolution” rate has been reported to be 0% to 66% of cases.5,20–22

FIGURE 12-2 Clinical photograph of a pediatric trigger digit of the long finger. Note the increased flexion posture with tenodesis and in the resting position. There is a trigger thumb present as well.

In what is often considered a classic paper on the subject, Dinham and Meggitt published a retrospective case series of 131 thumbs in 105 patients. In this investigation, 30% of patients presenting soon after birth demonstrated spontaneous resolution, whereas only 12% spontaneous resolution was seen when patients were observed or presented after 6 months of symptoms.

More recently, Baek et al.23 reported on 71 thumbs in 53 patients, and 63% achieved full IP joint extension at a mean age of 5 years. It should be noted, however, that mean flexion contracture was 26 degrees at presentation, and no information was provided regarding the indications or number of patients undergoing surgical release during the study period. Furthermore, while a majority of patients attained full extension, given the ability for young children to hyperextend the IP joint, it is unclear whether full extension can be equated to spontaneous resolution. Similarly, there was no information about the degree of thumb flexion; unresolved trigger thumbs can present with an extension contracture rather than flexion contracture as expected.

Limited information also exists regarding the role of splinting or formal therapy and stretching on the natural history of the symptomatic pediatric trigger thumb. While some reports have cited “success” or “satisfactory results,” many of these patients had abnormal final motion, and questions of compliance and duration with splinting therapy remain.24–26

Even less is known about the natural history of pediatric trigger fingers. Indeed, the natural history may never be truly established given the infrequency with which these occur and the heterogeneity of etiology and clinical presentation. While anecdotal reports exist of improvements with observation, stretching, or nighttime extension splinting, most of the smaller retrospective case series suggest that surgical treatment is required to eliminate the triggering.

Surgical Indications

Surgical indications for trigger thumb release continue to evolve, particularly given changing information regarding natural history. At present, we recommend surgical release for fixed flexion contractures or symptomatic and functionally limiting triggering in patients >18 months of age. We usually wait up to 6 to 12 months in the new presenting trigger thumb if the parents desire extended observation. We always closely examine the contralateral thumb and perform simultaneous bilateral releases if indicated (see Sidebar).

For patients with trigger fingers, surgical release is recommended after 6 months of failed observation and/ or nighttime splinting or if the digit is locked. We obtain a preoperative x-ray of the trigger digit(s) to check for calcific tendonitis.

The Argument for Early Surgery

I watched the Indy 500, and I was thinking that if they left earlier they wouldn’t have to go so fast.

—Steven Wright

Despite published information that many cases of trigger thumbs may spontaneously resolve over time, a number of disadvantages of observation bear notice. First, in the most recent prospective evaluation on the natural history of pediatric trigger thumbs, spontaneous resolution (as defined as full extension of the IP joint) occurred over 4 years. Therefore, if observation is chosen, patients/families should be aware of the long duration prior to expected resolution. Second, during the time that IP joint flexion contractures persist, compensatory hyperextension laxity of the MCP joint may secondarily develop due to the patient’s efforts to increase the first web space in cylindrical grasp. This MCP laxity may not completely resolve after A1 pulley release.31 Third, these patients may just exchange a flexion contracture for an extension contracture at the IP joint.

While there are a number of potential disadvantages to extended observation, there is relatively little downside to earlier operative release. The procedure is simple, straightforward, and associated with near universal success. Patients and families will see immediate improvements in IP joint motion and thumb use, leading to high patient satisfaction. Finally, secondary soft tissue or bony abnormalities may be avoided. For these reasons, compelling arguments can be made for earlier surgical release.

SURGICAL PROCEDURES

A1 Pulley Release for Pediatric Trigger Thumb

A1 Pulley Release for Pediatric Trigger Thumb

A hot dog at the ballgame beats roast beef at the Ritz.

—Humphrey Bogart

Trigger thumb release is performed in the operating room under general mask anesthesia. Esmarch bandage is utilized to exsanguinate the limb, and the bandage is wrapped around the proximal forearm or distal humerus three times to provide tourniquet control. The Notta nodule is palpated and marked with a marking pen at the level of the MCP flexion crease. Additional marks are made on either side of the nodule, defining the extent of the surgical incision (Figure 12-1). A transverse incision is then made through the dermis only in line with the MCP flexion crease. Great care is made to avoid incising too deeply during the skin incision, as the radial digital nerve and artery lie immediately below the skin and are at risk for iatrogenic injury Longitudinal spreading is performed on either side of the flexor tendon sheath, allowing the adjacent neurovascular structures to fall away and exposing the tendon sheath. Under direct visualization, the A1 pulley is then incised longitudinally. Its attachment to the periosteum and origin of the oblique pulley is released.27 The proximal flexor tendon sheath is released with spreading only to avoid injury to the crossing radial neurovascular bundle. The tendon is examined for abnormalities beyond the nodule by lifting it out of the wound with a retractor. If a cyst is present, it is excised. The nodule, however, is allowed to reabsorb on its own. Full passive stretching of the IP joint is performed, including the contracted volar plate. This resolves the trigger and IP joint contracture.

Although cast immobilization is not required, a durable, sterile bandage that will provide adequate wound coverage is needed. This may be reliably accomplished with the use of multiple layers of bandage material. A circular gauze covered by an ace bandage and stockinette is our bandage of choice; care is made to secure with adhesive tape all free edges that might allow the patient to remove the dressing. While Coban (3M, St. Paul, MN) may similarly accomplish these goals, caution is recommended when applying tight elastic bandages to any digit under anesthesia, particularly in the very young or nonverbal child.

Trigger Finger Release

Trigger Finger Release

Baseball is the only field of endeavor where a man can succeed three times out of ten and be considered a good performer.

—Ted Williams

Release of the A1 pulley is not sufficient in the treatment of pediatric trigger fingers. In up to 44% of cases, isolated A1 pulley release will result in persistent triggering.28 For this reason, a number of expanded surgical strategies have been proposed, including incision of the A3 and part of the A2 pulley as well as widening of the FDS decussation.29

Trigger finger release is performed under general anesthesia (Figure 12-3). Because more extensive release may need to be performed, an extensile zigzag Bruner incision is made. With retraction and protection of the adjacent neurovascular bundles, the A1 pulley is incised. Intraoperative proximal traction on the flexor tendons proximal to the A1 pulley allows for visualization of a proximal decussation of the FDS or a hypoplastic slip of the FDS tendon. A single slip of the FDS is then excised, taking care not to leave a prominent oblique stump that might lead to subsequent triggering. If a hypoplastic slip is identified, it is the one excised; if both are normal in appearance, the ulnar slip is excised. The digit is passively flexed and extended, and the flexor tendons are pulled proximally to confirm no residual triggering exists. Simple wound closure is then performed. The digit/hand is immobilized similar to trigger thumbs until the surgical wound heals, followed by early range of motion.

FIGURE 12-3 Surgical technique of trigger digit release. A: After extensile Bruner zigzag incisions, nodularity in the FDP tendon is seen adjacent to the FDS decussation. B: Triggering is resolved after excision of a single slip of the FDS.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree