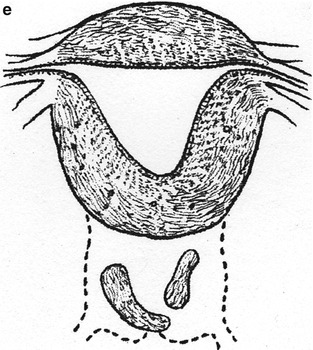

Fig. 23.1

Depictions of cervical agenesis and cervical dysgenesis (With permission from Rock and Jones [14]). (a) Cervical aplasia. (b) Cervical body consisting of a fibrous band of variable length and diameter that can contain endocervical glands. (c) The cervical body is intact with obstruction at the cervical os. Variable portions of the cervical lumen are obliterated. (d) Stricture of the midportion of the cervix, which is hypoplastic with a bulbous tip. No cervical lumen is identified. (e) Cervical fragmentation in which portions of the cervix are noted with no connection to the uterine body

Management

Current management recommendations are based on case reports and literature reviews; there have been no randomized trials to elucidate best surgical practice. This chapter summarizes surgical recommendations from several different reviews of the surgical literature with specific recommendations dependent on each patient’s specific cervical anatomy.

Traditionally, hysterectomy was advocated as the treatment of choice for these patients. Early attempts to create uterovaginal anastomosis resulted in a variety of serious surgical complications, including endometritis, pelvic inflammatory disease, sepsis, and injury to other pelvic organs including bowel and bladder. Even if a passage is created through fibrous tissue between the uterine cavity and the vagina, there are not typically functioning endocervical glands. The resulting absence of cervical mucus creates a difficult environment for sperm transport for patients desiring fertility.

Furthermore, patients are also subjected to long-term post-operative complications. Endometriosis can develop along the fistulous tract and these patients are also at higher risk for retrograde menstruation, increasing the likelihood of endometriosis in the pelvis [14]. The tract can re-stenose, requiring the need for repeat operations for further scar tissue [2, 14]. Recurrent pelvic infections after attempted fistulous tract formation can also eventually result in a hysterectomy and, if the infections are severe enough, bilateral oophorectomy [14].

Since the 1990s, however, there has been a shift towards attempting anastomosis of the utero-vaginal tract for reconstruction. This shift parallels advancement in surgical techniques and the availability of broad-spectrum antibiotics. There are, however, a few peri-operative considerations for patient selection to obtain higher rates of a successful surgical outcome, typically defined as long-term patency of the cervical canal, with subsequent cyclical menstruation and the possibility of pregnancy. Ideal surgical patients have a larger amount of cervical stroma and the presence of rudimentary endocervical glands. Rock et al. defines sufficient amount of cervical stroma as being at least 2 cm in diameter [15]. In addition, there should be a small discrepancy between the size of the uterine muscularis and vaginal stroma for ideal juxtaposition of the anastomotic site to decrease scarring [13]. Patients with vaginal agenesis tend to have more complicated surgeries due to the requirement of additional grafting of the neovagina.

As data for reconstructive surgery comes from smaller case reports, it is important to have an honest discussion pre-operatively with the patient disclosing the risks of surgery. In addition, it is helpful to obtain thorough imaging to attempt a pre-surgical diagnosis as noted above.

Once surgery is begun, the pelvic anatomy is carefully defined and the vesicouterine and rectouterine space are fully developed. It is imperative that the surgeon develop these spaces to determine whether there is sufficient cervical tissue for possible coring or anastomosis of cervical fragments. If reconstruction is not deemed feasible or if the uterine cavity is hypoplastic, a hysterectomy is performed [15].

If reconstruction is undertaken, surgical techniques vary depending on the amount of cervical tissue present. If there is a small amount of cervical obstruction or a small atretic segment of the endocervical canal with a normal vagina, the surgeon can perform a coring or drilling procedure. During this procedure, the cervix is cored to remove the obstruction. A catheter is left in place, optimally with a full- thickness skin graft around the catheter to allow the tract to epithelialize more rapidly [15]. If there is accompanying vaginal aplasia, the surgeon can perform a vaginoplasty using the McIndoe technique [15].

In the presence of cervical agenesis or dysgenesis with cervical fragments or a fibrous cord, a more extensive surgery, such as an uterovaginal anastomosis, is advocated.

A large case series published by Deffarges et al. in 2000 described the surgical technique of utero- vaginal anastomosis in 18 patients with cervical atresia. The patients underwent laparotomies with dissection of the vesicouterine and rectouterine space. An incision on the most superior portion of vaginal tissue was made and a channel formed between the bladder and the rectum until the abdominal anterior and posterior dissections were reached. A 10-mm dilator was inserted through an incision on the uterine fundus and placed at the most inferior portion of the uterus. The atretic vaginal tissue was resected in a similar technique as with a cervical conization until the uterine cavity was entered. The uterus was then sutured in a circumferential manner with 3-0 polyglactine. A 16 French Foley catheter was placed in the canal to maintain patency for 15 days and patients were given Ampicilin for the duration [4].

A similar technique was described by Creighton et al. however the authors incorporated the use of laparoscopy. Laparoscopically, sutures were placed on the uterus for uterine suspension. An incision was made in the uterine fundus with a harmonic scalpel and a probe placed in the uterus to identify the lowermost portion of the uterus, which was incised horizontally. A second probe was placed in the vagina and a laparoscopic incision made over the most superior portion of the vagina. A Foley catheter was passed between the vagina and the uterus and the uterus closed with 2-0 polydioxanone suture circumferentially at 12, 3, 6, and 9 o’clock. In this case, the Foley was left in place for 4 weeks and the anastomotic site remained patent [3].

Other case reports have discussed the need for accompanying the cervical reconstruction with a graft of the neocervical canal to allow for improved healing and decreased stenosis. Possible graft tissue includes full thickness skin grafts [15], bladder mucosa graft, or amniotic membrane (from a case describing reconstruction after cesarean section) [10].

Another surgical technique involves the use of end-to–end anastomosis for the cases of cervical dysgenesis with cervical fragmentation. Grimbizis et al. describes a patient with cervical fragmentation in a symmetrical transverse fashion. They created an end-to-end anastomosis during a laparotomy, connecting the central and distal portions of the cervix and then using a Foley catheter as a stent in the endocervical canal [8] (Table 23.1).

Table 23.1

Description of suggestive reconstructive surgical treatment

Anatomic findings | Suggested reconstructive surgical treatment

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

|

|---|