Gary D. V. Hankins, MD

George R. Saade, MD

• Narrow QRS-Regular Tachycardias

• Narrow QRS-Irregular Tachycardias

• Wide QRS-Regular Tachycardias

• Wide QRS-Irregular Tachycardias

1. Wolff-Parkinson-White Syndrome

INTRODUCTION

Complex arrhythmias are uncommon during pregnancy because of the relative young age and low prevalence of cardiac disease among pregnant women. In the near future, the increase in maternal age and concomitant medical diseases, such as obesity, chronic hypertension, diabetes with vasculopathy, and the fact that women are reaching childbearing age after surgical correction of congenital heart disease may increase the prevalence of arrhythmias during pregnancy.

The management of most arrhythmias during pregnancy is similar to standard practice applied to nonpregnant individuals. This chapter addresses the diagnosis and management of the most common arrhythmias found in clinical practice.

TACHYARRHYTHMIAS

In most cases, heart rates above 150 beats per minute (bpm) are required for hemodynamic instability to occur. The mechanism by which the tachycardia leads to instability is related to the fact that at high heart rates, the ventricular filling time (time required to fill the left and right ventricles with blood) will be shorter than normal resulting in a reduction in stroke volume.

When caring for a patient with a tachyarrhythmia, the first step is to determine whether the patient is stable. If the patient has signs and symptoms of hemodynamic instability (eg, hypotension, angina, pulmonary edema, and confusion), then immediate synchronized electrical cardioversion is indicated. In stable patients, the pharmacological treatment is commonly indicated depending on the mechanism of the arrhythmia.

The first step in classifying the event is to divide them into either narrow or wide QRS (a wide QRS complex measures more than 0.12 seconds). Narrow QRS tachycardias may be either regular or irregular (depending on the distance between R waves on consecutive QRS complexes). Wide QRS tachyarrhythmias may be further subdivided into regular and irregular.

When caring for patients with new-onset arrhythmias, the clinician should look for potentially reversible causes, such as electrolyte abnormalities (as a general rule, maintain a potassium above 4 mEq/L and magnesium above 2 mg/dL), pH disturbances, as both alkalemia and acidemia may exacerbate arrhythmias, and, in cases of arrhythmias after central line placement, immediate assessment by chest X-ray is required to rule out the possibility that the tip of the catheter is inside the right atrium or right ventricle as its presence may precipitate arrhythmias. Thyroid evaluation with a thyroid-stimulating hormone level may also be indicated depending on the clinical presentation. Structural heart abnormalities need to be ruled out with a transthoracic echocardiography.

Narrow QRS-Regular Tachycardias

This first group includes the following: sinus tachycardia, atrial flutter with consistent atrioventricular conduction, atrioventricular nodal re-entrant tachycardia, atrioventricular reciprocating re-entrant tachycardia, and atrial tachycardia.1

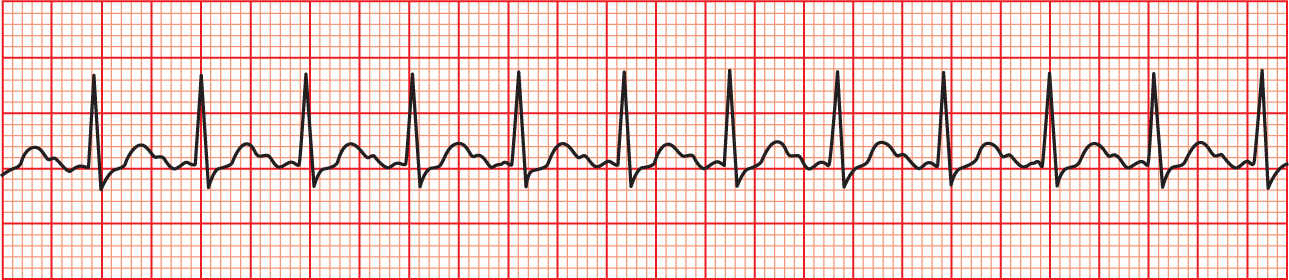

The clinician should first rule out the possibility of a simple sinus tachycardia as this is commonly secondary to treatable conditions, such as pain, anxiety, hypovolemia, and fever. In general, sinus tachycardia has a gradual onset, and each QRS is preceded by a P wave (see Figure 7-1). During pregnancy, heart rate at 17% above baseline is normally seen.2

FIGURE 7-1. Sinus tachycardia. R-R interval is regular, each QRS is preceded by a P wave.

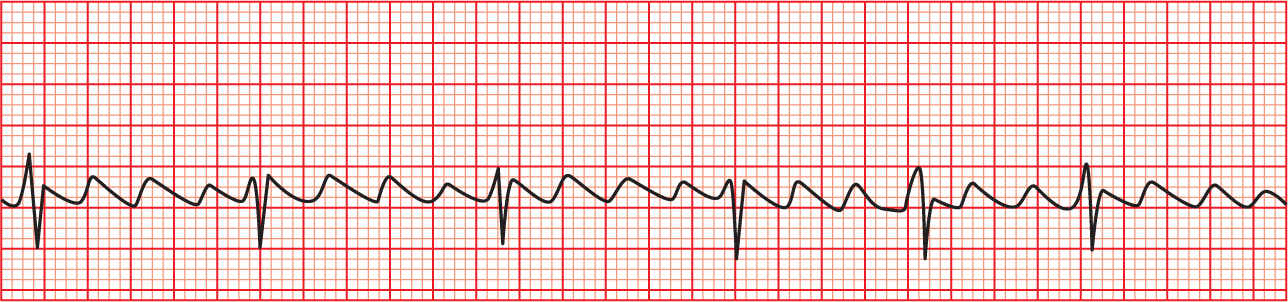

Atrial flutter may present with a regular R to R interval if the atrioventricular conduction is constant. For example, if the atria contracts twice but during that time the electrical impulse consistently travels only once to the ventricles (thanks to the physiologic delaying of conduction seen in the atrioventricular node), then a constant “2 to 1” atrial flutter is present and the QRS will be narrow and regular. Atrial flutter should be suspected when an abrupt increase in heart rate to 150 bpm is seen, as in most cases the atrial rate is around 300 bpm and the conduction is “2 to 1,” resulting in a ventricular rate of 150 bpm.1 The flutter waves on surface electrocardiogram are commonly seen (see Figure 7-2).

FIGURE 7-2. Atrial flutter. Note atrial flutter waves with a 3:1 conduction.

If a patient presents with atrial flutter and shows signs/symptoms of hemodynamic instability, immediate synchronized electric cardioversion is indicated with 50 to 100 J (initial energy; higher levels may be required if subsequent shocks are required).3 Electric cardioversion and defibrillation are safe during pregnancy and should be used if indicated.4 If fetal monitors are in place, some recommend removing them to prevent electrical arcing although the evidence to support this is minimal. If the patient is stable in the setting of a new-onset atrial flutter, treatment should be directed toward slowing the ventricular response with the use of agents, such as beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, digoxin, or amiodarone. Beta-blockers, such as metoprolol or esmolol, and nondihydropyridine calcium channel blockers, such as diltiazem, are considered first-line therapy. In patients with compromised cardiac output, the use of digoxin or amiodarone may be considered.3 Amiodarone should be reserved for refractory cases as it crosses the placenta and may lead to fetal hypothyroidism, hyperthyroidism, and goiter.5

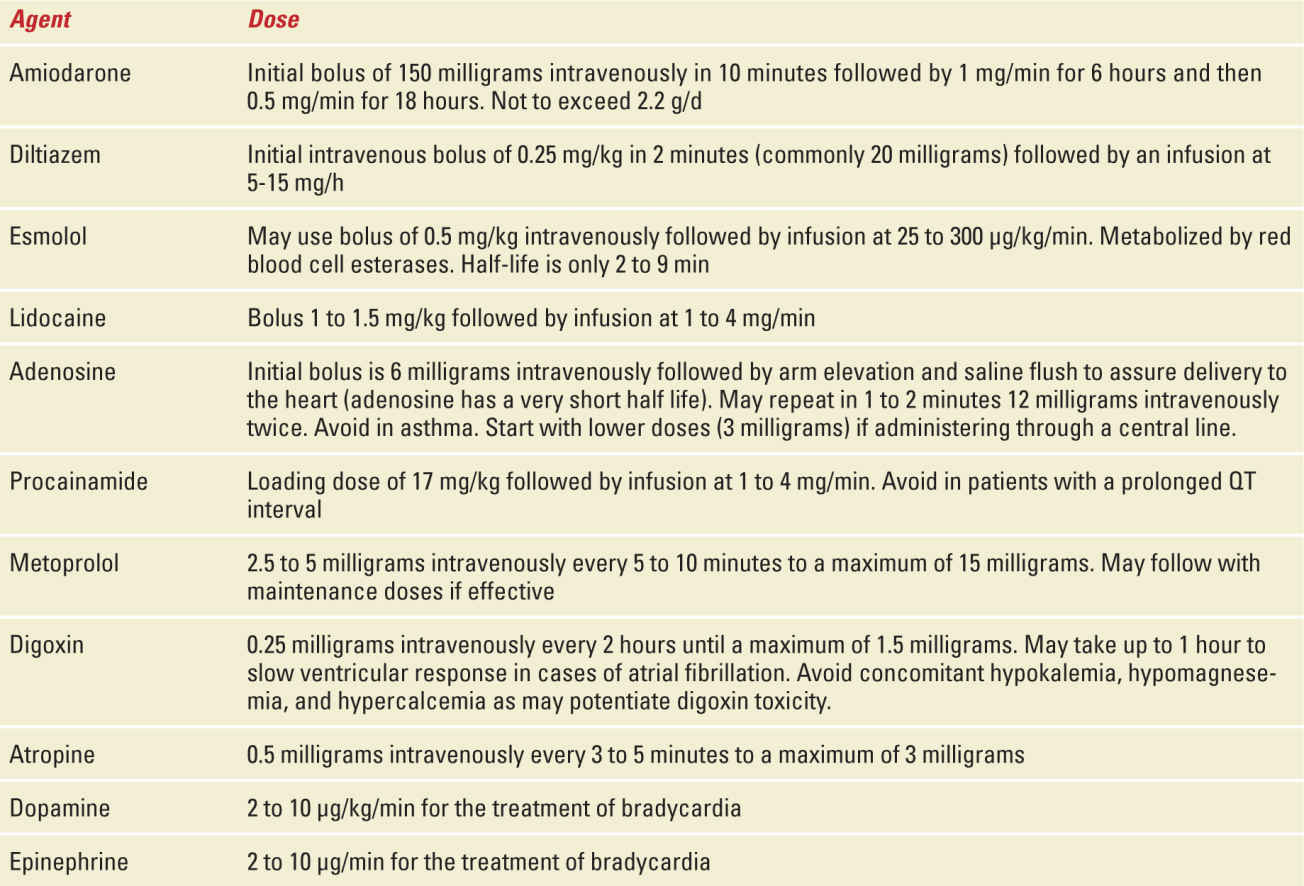

It is not clear what constitutes an adequate ventricular rate, but a rate less than 110 bpm is reasonable in the setting of atrial fibrillation and thus may be extrapolated to atrial flutter.6 Table 7-1 provides a guide on dosages and therapeutic indications of the different antiarrhythmics discussed in this chapter.

TABLE 7-1 | Commonly Used Antiarrhythmic Agents |

The third group of tachycardias in this category includes the re-entrant tachycardias (nodal re-entrant or reciprocating), commonly referred to as paroxysmal supraventricular tachycardias. In adults, most of these are nodal reentrant tachycardias (see Figure 7-3) with an accessory pathway found at the level of the atrioventricular node. Reciprocating re-entrant tachycardias are more common among children.1 Re-entrant tachycardias commonly present with an abrupt onset and termination of the arrhythmia with rates between 150 and 250 bpm. Just like any other tachyarrhythmia, if the patient shows signs/symptoms of hemodynamic instability, then immediate synchronized electrical cardioversion is indicated. The initial current to be used is 50 to 100 J. If the patient is stable, it is reasonable to attempt vagal maneuvers (Valsalva maneuver, carotid massage, submerging the face in cold water) as the increased parasympathetic tone may resolve up to 25% of these arrhythmias.7 If vagal maneuvers are unsuccessful, adenosine is the first-line agent for re-entrant tachycardias. Virtually all will stop with adenosine, and failure of adenosine to terminate the arrhythmia should alert the clinician of an alternative diagnosis.1

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree