Travel Medicine

Joseph A. Zenel and Chandy C. John

Travel involves leaving the familiar to experience a new environment. Travel risks exposing oneself to both known and unknown germs, safety hazards, and unfamiliar health care.  Pre-ravel preparation for health care needs can help alleviate unexpected challenges that may hamper travel. The online chapter includes a discussion on travel preparation for overall health and acute and chronic illnesses, including sections on General Preparation, Overall Health, Medical Concerns: Acute Illness, Medical Concerns: Chronic Illness, Immunization, Routine Childhood Immunizations in the United States, and Infections through Contact with Infected Persons or Needle Exposure.

Pre-ravel preparation for health care needs can help alleviate unexpected challenges that may hamper travel. The online chapter includes a discussion on travel preparation for overall health and acute and chronic illnesses, including sections on General Preparation, Overall Health, Medical Concerns: Acute Illness, Medical Concerns: Chronic Illness, Immunization, Routine Childhood Immunizations in the United States, and Infections through Contact with Infected Persons or Needle Exposure.

GENERAL PREPARATION

Preparation for travel should include evaluation of the traveler’s overall health, the travel itinerary (location, extended, extreme, wilderness, diving, climbing, spelunking), conditions associated with travel, conditions associated with the destination environment, personal safety and security, available health care, the contents of an emergency medical kit. Specific health concerns to consider are infection, accidents, environmental exposures, physician availability, hospitalization, medical evacuation, and health insurance.5 An excellent source for information on traveling with children is the Web site sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Traveler’s Health: Yellow Book at http://wwwn.cdc.gov/travel.

Routine medical and dental care, including routine booster immunization, should be reviewed and updated prior to travel. Any recommended immunization and prophylaxis therapy for travel destinations should begin at least 6 weeks before departure. Sufficient supply of routine prescribed medications, medical supplies (inhalers, syringes), sunscreen, and insect repellents should be packed before departure. Proper documentation, including birth certificate or passport, immunization records, health record summary, list of prescribed generic medications, list of personal physician(s), and health insurance information should be carried on person during travel. Documentation duplicates can be packed in checked luggage.1 Families should learn the location of health care facilities and physician services in points of destinations and obtain adequate travel and medical evacuation insurance.

MEDICAL CONCERNS DURING TRAVEL

When traveling, early signs and symptoms of possible severe illness, such as high fevers, lethargy, sudden irritability, dehydration (dry mouth, no tears), persistent diarrhea, and respiratory distress, should alert parents to seek medical attention. Parents should learn emergency phone numbers and how to contact local medical clinics prior to arriving or upon arrival at the final destination. Having personal medical history documentation on hand (preferably signed by personal physician) will help facilitate timely treatment. If drug compounding, injection, intravenous catheterization, or blood product transfusion is necessary, parents should inquire about and/or observe preparation and procedure to ensure patient safety. If parents seek alternative care, such as acupuncture, the same concerns apply.

Care should be taken to accommodate children with chronic disease and disabilities. It is best to carry an adequate supply of medications and supplies (eg, inhalers) during travel because certain drugs may be difficult to obtain in other countries, and those available may be costly, impure, or incorrectly concentrated. This is particularly true for obtaining medications for children with attention deficit disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, or depression. Having written prescriptions of current generic medications on hand may help replacement of lost or depleted medications. If a child frequently requires emergent blood transfusions (eg, sickle cell disease, hemophilia), families should plan for this possibility and contact appropriate health care facilities prior to travel.

For handicapped children, advance notice to airlines or other transportation agencies helps facilitate accommodation and on-time scheduled trips and avoids accidental injuries. Arrangements for physical, occupational and speech therapy should be made in advance because these services are generally hard to find while abroad.

For children requiring technology-dependent therapies (eg, nebulizers, oxygen supplementation, home mechanical ventilation), provisions should include adequate power supply (eg, batteries, power plug adapters).

INFECTION

IMMUNIZATION

IMMUNIZATION

The primary reason children are seen in travel clinics or at a pediatrician’s office specifically for travel evaluation is to receive required or highly recommended vaccines not typically needed in the United States. While many parents request the visit specifically for this reason, they are not aware of the other travel-related health issues that may affect their child. The travel visit is a good chance to educate parents on infectious and noninfectious travel health issues for their child. Travel immunizations can be expensive and are often not covered by insurance plans. Parents should be made aware of the costs of immunizations and the frequent lack of insurance coverage for these immunizations.

Incomplete immunization is not uncommon in children from the United States traveling to other countries. It is important to emphasize to parents, particularly parents who are opposed to all vaccination, that their child’s risk of many vaccine-preventable diseases is significantly higher in many countries outside the United States, particularly developing countries, than it is in the United States. Children should be fully immunized with all routine childhood vaccines prior to travel. Complete information on routine immunizations, including schedule, adverse effects, contraindications, and special indications, is summarized in Chapter 245, “Immunizations.” This chapter focuses on details about routine immunization germane to children traveling internationally. An accelerated vaccination schedule is available for children who have missed 1 or more immunizations (eTable 18.1  ). Complete information on childhood and adolescent immunizations is available on the CDC Web site (http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/schedules). The following discussion is focused on details about routine immunization germane to traveling internationally.

). Complete information on childhood and adolescent immunizations is available on the CDC Web site (http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/recs/schedules). The following discussion is focused on details about routine immunization germane to traveling internationally.

Travel Vaccines

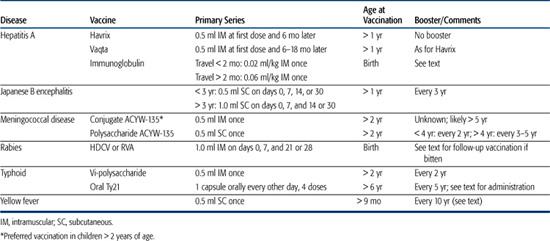

The dosages and age restrictions of vaccines specifically for children traveling internationally are summarized in Table 18-1.

Cholera Cholera is present in many developing countries, but the risk of infection among travelers to these countries is very low. A new oral live cholera vaccine that is effective against most cholera strains is available in Canada and Europe for children older than 2 years, but no cholera vaccine is currently available in the United States. No country or territory currently requires cholera vaccination.

Hepatitis A See Chapter 245.

Japanese Encephalitis Japanese encephalitis is transmitted by night-biting mosquitoes in rural areas of Asia, where people are in close proximity to livestock. The vast majority of infections are asymptomatic, but when symptomatic, the disease can have up to a 30% case fatality rate. The risk in travelers is less than 1 case per million travelers, but the risk is highest in children.7 Disease generally occurs from June to September in temperate zones and throughout the entire year in tropical zones. Parents of very young children should be discouraged from traveling with their children to high-risk areas. Vaccination is recommended for travelers planning visits of greater than 1 month to rural areas of Asia where the disease is endemic, especially areas of rice or pig farming, or shorter visits to these areas if the traveler will be camping, hiking, or frequently engaged in other outdoor activity or work. Precautions to avoid mosquito bites reduce the risk of infection.

The inactivated Japanese encephalitis vaccine has a high efficacy (> 95%), but local reactions occur in up to 20% of vaccine recipients, mild systemic reactions (headache, myalgias, and rash) in 10%, and hypersensitivity reactions including urticaria and angioedema in up to 0.6% of vaccine recipients. Hypersensitivity reactions may occur within minutes but may delay as long as 2 weeks after vaccination. The vaccination series, given on day 0, 7, and 30 (Table 18-1), should be completed at least 10 days before travel so that any adverse reactions to the vaccine can be observed and treated. A booster dose is given at 24 months if exposure risk remains high. The vaccine may be used in children over 1 year of age (Table 18-1).

Meningococcus Neisseria meningitidis causes epidemic and endemic disease worldwide. Most cases occur in the “meningitis belt” of sub-Saharan Africa between December and June. Epidemics have also occurred in the Indian subcontinent and Saudi Arabia among pilgrims to the Haj. Saudi Arabia requires all pilgrims to Mecca to have documentation of meningococcal vaccination 10 or more days but less than 3 years before arrival. Cases of meningococcal disease in American travelers to other areas are rare. Vaccination is indicated primarily in travelers to an area with an active outbreak or those who may have prolonged contact with the local population in an endemic area, especially in crowded conditions. Serogroup A is the most common cause of epidemics outside the United States, but serogroup C and, rarely, serogroup B have also been associated with epidemics. For a discussion of the meningococcal vaccines, see Chapter 244 and the DVD.

Rabies Rabies is discussed in Chapter 321. Rabies is endemic in many countries in Africa, Asia, and Central and South America. Children, who are more likely to receive facial bites, and hikers in remote areas are at higher risk. Preexposure rabies prophylaxis should be considered if a child will be in an endemic area for longer than 1 month or will be traveling to an area where rapid, effective postexposure prophylaxis may not be available. In a rabies-endemic area, an animal bite is a medical emergency, and this point should be emphasized to parents and adolescents. Immediate medical care must be sought at a facility that can administer appropriate postexposure rabies prophylaxis. Ideally, the animal in question should be caught and quarantined for 10 days of observation for signs of rabies. Postexposure prophylaxis is required even for individuals who received preexposure vaccination. This should be made clear to those who receive preexposure prophylaxis so that they understand that preexposure vaccine does not eliminate all risk for the disease. Further details of vaccination issues are provided on the DVD.

Typhoid Salmonella typhi infection (typhoid fever) is discussed in Chapter 283. It is common in many developing ountries in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. Typhoid vaccination is recommended for children traveling to the Indian subcontinent, the area of highest risk, and for individuals traveling to endemic areas who are at higher risk of infection, particularly children visiting developing countries, as well as long-term travelers (those traveling for more than 4 weeks) and backpackers. Vaccination should be strongly considered for all children over 2 years old who are traveling to endemic areas. Further details of vaccination issues are provided on the DVD.

Table 18-1. Travel Vaccinations for Children

Yellow Fever Yellow fever is a mosquito-borne viral hemorrhagic illness, sometimes accompanied by severe hepatitis and liver failure leading to jaundice, hence the name “yellow fever.” It is further discussed in Chapter 307. Yellow fever is present in tropical areas of South America and Africa.

Some countries require proof of yellow fever vaccination from all entering travelers. Current requirements can be obtained on the CDC Web site (http://www.cdc.gov). Most countries accept a medical waiver for children who are too young to be vaccinated (less than 4 months old) and for individuals with a contraindication to vaccination, such as immunodeficiency. Children with asymptomatic HIV infection may be vaccinated if exposure to yellow fever virus cannot be avoided. Further details of vaccination issues are provided on the DVD.

TRAVELER’S DIARRHEA

TRAVELER’S DIARRHEA

Traveler’s diarrhea is the most common travel-related illness in children and adults.10 Traveler’s diarrhea is acquired through contaminated food or water. Numerous bacterial, viral, and protozoal pathogens are associated with traveler’s diarrhea. Enterotoxigenic Escherichia coli is still the most common cause. Other bacterial causes include Shigella, Salmonella, Campylobacter, Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, Aeromonas hydrophilia, and Plesiomonas shigelloides. The most common protozoal cause of traveler’s diarrhea is Giardia lamblia. Giardiasis may also present with bloating, stomach cramps, or abdominal pain. Other protozoal causes such as Entamoeba histolytica, Cryptosporidium parvum, and Isospora are more common in long-term travelers. Rotavirus and other viral pathogens may also cause traveler’s diarrhea. High-risk areas for traveler’s diarrhea (attack rates of 25–50%) include developing countries of Latin America, Africa, the Middle East, and Asia. Intermediate risk occurs in the Mediterranean, China, and Israel. Low-risk areas include North America, Northern Europe, Australia, and New Zealand. Drinking only safe water and attention to proper preparation of food can reduce the risk of developing traveler’s diarrhea (see “Water” and “Food” in this chapter). Chemoprophylaxis for traveler’s diarrhea is not recommended for children.

Dehydration is the primary risk in children with traveler’s diarrhea. Parents should be aware of the availability of oral rehydration solution packets in most developing countries and of the importance of using bottled or boiled water with the solution to prevent or treat dehydration. Bismuth subsalicylate given every 4 hours (16.7 mg/kg/dose, or 100 mg/kg/day), decreases the rate of stooling and shortens the duration of illness.11 Higher doses should be avoided to avoid salicylate toxicity, and bismuth subsalicylate should not be given to a child who has or might have influenza, because salicylates may increase the risk of Reye syndrome in children with influenza. Antimotility agents such as diphenoxylate (Lomotil) and loperamide (Imodium) should be avoided in children under 8 years. In children over 8, loperamide (2 mg orally, up to 3 times a day) may be useful in decreasing stool frequency if the child does not have a high fever or bloody stools.

Presumptive treatment of traveler’s diarrhea is recommended in children and adults, though there is little pediatric data on the efficacy of this treatment. The drug of choice for children is azithromycin (10 mg/kg/day, maximum dose of 500 mg, for 3 days). Ciprofloxacin (25–30 mg/kg/day, divided into 2 doses, maximum dose of 500 mg twice a day, for 3 days) is an acceptable alternative.12 Azithromycin is not specifically approved for the treatment of diarrhea, but it is highly effective against most pathogens that cause traveler’s diarrhea and can be prescribed in powder form that can be made into a liquid suspension when needed. Ciprofloxacin is not approved for use in children but has been used extensively and shown to be safe in children.13 Prescriptions for one or the other medication should be given to parents to fill and take with them when they travel with their children or given to the child if the child is an adolescent traveling alone or with a group. Infants and young children who have significant diarrhea should seek medical attention, particularly if stools are bloody or the child has a high fever (over 102 °F), chills or moderate to severe dehydration.

MALARIA CHEMOPROPHYLAXIS AND PROTECTIVE MEASURES

MALARIA CHEMOPROPHYLAXIS AND PROTECTIVE MEASURES

Protective measures and insect avoidance are critical to protection against malaria because no chemoprophylaxis completely protects against the disease (see “Environmental Concerns” in this chapter). In addition to these measures, chemoprophylaxis should be taken by all children traveling to malaria-endemic areas. Malaria chemoprophylaxis is covered in detail in Chapter 352, eTable 18.2  , and in additional text on the DVD.

, and in additional text on the DVD.

TUBERCULOSIS

TUBERCULOSIS

Many countries in sub-Saharan Africa, the Indian subcontinent, and Southeast Asia have a very high incidence of tuberculosis, and multi-drug resistant tuberculosis is increasing in frequency in several of these countries. However, tuberculosis requires exposure to an infectious human, and most children traveling internationally are at low risk because they do not have this contact. The children at highest risk are those visiting friends and relatives in a developing country and/or those children living in a developing country for a prolonged period of time.15 Tuberculin skin testing should be performed before and after prolonged travel to a country with a high incidence of tuberculosis, and tuberculosis should be considered in any child who has been to a country with high rates of tuberculous disease within the past year and has an unusual or persistent pneumonia, persistent fever, weight loss, or unexplained bone pain accompanying fever.

PARASITIC DISEASE

PARASITIC DISEASE

Numerous parasitic diseases are common in developing countries. Travelers are at low risk for most of these diseases. Among the parasitic diseases, travelers are most often exposed to intestinal parasites like Giardia lamblia that cause gastrointestinal symptoms (see “Traveler’s Diarrhea” in this chapter) and/or that eventually lead to worm excretion in the stool (eg, Ascaris lumbricoides). These parasites are usually acquired by contaminated food or water. Other parasitic infections for which the child traveler may be at risk include schistosomiasis (walking or swimming in infected rivers, lakes, or pools of water), hookworm or Strongyloides stercoralis infection (walking without shoes in muddy areas), cutaneous larva migrans due to Toxocara canis (walking barefoot on beaches in areas where dogs have defecated), and botfly infections of the skin.

WATER

WATER

Most travelers are aware of the risk of ingesting coliforms and parasites from drinking contaminated or poorly treated water. Most large, industrialized cities have modern treatment plants and water supply, but older homes and other locales may use water sources such as wells or cisterns that are not adequately treated. In general, travelers should use only bottled water for drinking, making ice, and brushing teeth. If bottled water is unavailable, then travelers should use water purifier filters or tablets.

Despite close supervision, children are more likely than adults to drink water of questionable quality. Care should be taken to prevent children from drinking bath water, local fresh water (ponds, lakes, streams), and public fountain water.

FOOD

FOOD

Food is a more common source for disease than water. Travelers risk developing diarrhea or other illnesses by ingesting food contaminated by bacteria or parasites due to rinsing with untreated water, improper hygiene by food handlers, improper refrigeration, inadequate food heating and preparation, or by ingesting insecticides (organophosphates) through improperly washed foods. Foods that are generally safe include packaged cereals, bread and pasta, canned foods and juices, and pasteurized dairy products.1 Cooked meals should be served and eaten hot or steaming; salad bars and cold buffets risk contamination. It is best to avoid food or drinks sold by street vendors as well as fresh fruits or vegetables that cannot be washed or peeled.

ENVIRONMENTAL CONCERNS

The vacation or destination environment may pose significant risks to health. Examples are access to open bodies of water and exposure to contaminated soil, sun, air pollutants, cold, lead, insects, and insecticides. Drowning is one of the major causes of morbidity and mortality in children during travel. Furthermore, swimming in bodies of fresh or salt water and walking barefoot in soil or sand may expose children to bacterial pathogens and parasites. Poor air quality may provoke respiratory illness in children with chronic lung disease such as asthma and cystic fibrosis. Children undergoing sun exposure during summer months, high-altitude climbing, and traveling in areas closer to the equator are more prone to sunburn and should be protected by sunscreen and/or sunblock. Sunscreen should have an SPF of 15 or more to be effective. Children should wear warm, protective clothing during extreme cold exposure during winter months, high-altitude climbing, or traveling in areas closer to the Arctic and Antarctic circles. Lead can be found in gasoline, paint, cosmetics, jewelry, and over-the-counter medications throughout the world.

Insect avoidance is the only effective means to prevent infection transmitted by insect bites (eg, malaria, Rocky Mountain spotted fever, yellow fever, West Nile virus–associated illness). Protective clothing should be light-colored and should effectively cover the arms, legs, ankles, and feet. DEET (N,N-diethyl-m-toluamide) and Picaridin (KBR 3023) are commonly used insect repellents recommended for children 2 months of age or older. DEET is available in concentrations ranging from 5% to 100%, yet no more than 30% DEET should be used in children because of concerns for neurotoxicity. Applying 30% DEET provides about 5 hours of protection; 10% DEET provides 1 to 2 hours of protection. Picaridin, approved in the United States in 2005, is available in concentrations of 5% to 10% and provides protection for 1 to 2 hours.16 Unlike DEET, Picaridin is odorless, has no oily residue, and is less likely to damage clothing. Insect repellents should be applied only to exposed skin and, when used during the day, should be applied 30 minutes after applying sunscreen. Applying permethrin to clothes and bed linen is another effective way to prevent insect bites.

AIR TRAVEL

Air travel can produce illness because of its unique isolated environment. Most cabins are pressurized to an altitude equivalent to 6000 to 8000 feet above sea level, while the cabin may be flying at altitudes up to 30,000 feet. This increase in cabin pressure will cause a small decrease in blood oxygen saturation along with expansion of gases in body cavities, thereby inducing middle ear, sinus, chest, and gastrointestinal tract discomfort. Since children in airplanes can experience up to a 5% decrease in blood oxygen saturation during flight, children with upper respiratory infections or sickle cell disease may experience discomfort or pain, and children with heart or lung disease may undergo respiratory distress and require oxygen supplementation.17,18 Other illnesses may occur, in part due to a missed medication dose.

Children held on adult laps may be injured during turbulence and nonfatal crashes. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that children under 1 year of age and weighing less than 20 pounds should be placed in a rear-facing Federal Aviation Authority (FAA)-approved child-safety seat. A forward-facing FAA-approved child safety seat is appropriate for children older than 1 year who weigh 20 to 40 pounds. Children weighing 40 pounds or more can use the aircraft seat belt.

Frequently, children develop ear pain inflight, particularly during descent. To achieve eustachian tube decompression, infants and children should be encouraged to swallow or chew. Infants can breast feed or suck on a bottle, and older children can chew gum or try blowing against their own closed mouth and pinched nose. Antihistamines and decongestants are of no benefit for preventing ear pain during flight.

SPECIFIC TRAVEL-RELATED ILLNESSES

JET LAG

JET LAG

Traveling through different time zones generally disrupts sleep patterns in infants and children, though not as much in adults. Shifting a child’s sleep schedule 2 to 3 days prior to travel may be helpful. Eating meals and sleeping during appropriate times for the time zones encountered during travel and immediately upon arrival helps adjust sleep schedule. After arrival, children should be encouraged to be active outside during early sunlight hours when traveling east and in afternoon sunlight hours when traveling west. In general, medicating infants and children to treat sleep disturbance during travel should be avoided. Sedative medications can cause paradoxical agitation or respiratory depression, and melatonin may have effects on sexual development in infants and children. Diphenhydramine’s sedating effects may help induce sleep, but again, some children may have paradoxical agitation.17

MOTION SICKNESS

MOTION SICKNESS

Motion sickness is a common problem for children traveling by automobile, train, sea, and air. For children under 5 years, motion sickness may manifest by ataxia. For older children, symptoms include nausea, vomiting, pallor, sweating, and vertigo. Preventive measures include minimizing head movement and sitting in areas of the smoothest ride, such as the front seat of a car, front of a train, and center of a boat. Antihistamines and anticholinergics are frequently used medications to treat and prevent motion sickness in adults. For children, diphenhydramine and dimenhydrinate are commonly used drugs. Scopolamine should not be used in children under 12 years old.21

ALTITUDE SICKNESS

ALTITUDE SICKNESS

Altitude sickness, also known as acute mountain sickness, occurs with rapid ascension to higher altitudes, strenuous exercise, and insufficient acclimatization. At high altitudes, air pressure decreases, leading to less partial pressure of oxygen in the body. Fluid leakage from blood vessels starts to occur. Severe complications are high-altitude cerebral edema (HACE) and high-altitude pulmonary edema (HAPE); retinal hemorrhages and peripheral edema can also occur. Common symptoms are headache with fatigue, irritability, nausea, vomiting, dizziness, and sleep disturbance. Acetazolamide, dexamethasone, and nifedipine have been shown to be effective in preventing altitude sickness in adults. Acetazolamide is thought to be safe for children, and the recommended dose is 5 mg/kg/day divided twice a day to three times a day; acetazolamide is contraindicated in persons with allergy to sulfa. Treatment consists of descent to a lower altitude, oxygen therapy, rest, warmth, and possibly intravenous steroids.22

DECOMPRESSION ILLNESS

DECOMPRESSION ILLNESS

Rapid ascent from deep scuba diving to the surface can cause overexpansion of air in the lungs and nitrogen to bubble in the blood stream and tissues. Symptoms include chest pain, arthralgias; numbness, tingling, mottling, or marbling of skin; coughing spasms, shortness of breath; itching; unusual fatigue; dizziness, weakness; personality changes; loss of bowel or bladder function; staggering, loss of coordination, tremors; paralysis; and collapse or unconsciousness. Treatment consists of hyperbaric oxygen chamber therapy.23

SPELUNKING

SPELUNKING

While cave exploring, children are at risk for injuries due to falls and exposure to rabies due to contact with bats, bat saliva, and urine.

SAFETY

TRANSPORTATION

TRANSPORTATION

Automobile accidents are the major cause of morbidity and mortality for children during travel. Motor travel in some foreign countries is risky because of overcrowded vehicles and lack of customary car-safety devices. A car seat should be used for any child under 6 years of age while traveling abroad. Night driving should be avoided, as should unscheduled flights or flights on airlines with poor safety records.24

POLITICAL

POLITICAL

Unfortunately, civil unrest, crime, and terrorism threaten the safety of travelers in some countries. Roadside stops should be planned in advance, preferably in well-known, safe public places. The CDC, the US State Department, the International Society of Travel Medicine, and the Association for Safe International Road Travel are excellent resources for up-to-date information on global safety. If the travel destination is a country undergoing political unrest, it is best to contact the US embassy upon arrival.24

TRAVEL KIT

Families vacationing at a location far from medical facilities or traveling abroad should carry a travel first aid kit that can address more than the usual emergencies encountered at home. Contents depend on destination and could include medical records; doctors’ names; contact numbers; insurance information; duplicate prescriptions; first aid supplies; prescription medicines; medicine for motion sickness, diarrheal illness, and altitude sickness; water purification materials; insect repellent; sunscreen; malaria prophylaxis; medical supplies (eg, insulin syringes, inhaler); and plug adapters for foreign electrical currents. eTable 18.3  suggests a more detailed travel kit.1,17

suggests a more detailed travel kit.1,17

INFORMATION RESOURCES

Local travel health clinics, the US State Department, and the host country health department are good sources for information on travel preparation. Every 2 years, the CDC publishes Health Information for International Travel, also known as the Yellow Book. For Internet access to the Yellow Book or other up-to-date region-specific and country-specific travel information, including safety, security, and how to maintain health during and after a trip, go to http://wwwn.cdc.gov/travel.

Following are other good Internet sources for information on traveling abroad:

1. http://www.istm.org: This official Web site for the International Society of Travel Medicine provides a travel clinic directory and outbreak news.

2. http://www.astmh.org: This official Web site for the American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene provides a travel clinic directory and information on tropical diseases.

3. http://www.asirt.org: This official Web site for the Association for Safe International Road Travel provides road travel reports and information on global safety.

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree