Emily Stimpson, RN, MSN, CCTC

Kristine Acorda Reece, RN, MSN, ANP-BC, CCTC

Vincent G. Valentine, MD, FACP, FCCP

• Solid-Organ Transplantation in the United States

• Pregnancy in the United States

1. Solid-Organ Transplantation and Pregnancy in the United States

GENERALITIES ON PREGNANCY AND SOLID-ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION

SCOPE

Solid-Organ Transplantation in the United States

Although solid-organ transplantation began in 1954 with kidney transplantation in the United States, all other organs including liver, heart, and lung were not consistently and durably successful until about three decades ago. The first successful liver transplant was performed in 1967 and the first successful heart in 1968. It was not until after the introduction of cyclosporine which made it possible for the first successful lung transplantation procedure to occur in the form of combined heart-lung transplantation in 1981. The first successful single and double lung transplantation procedures occurred in 1983 and 1986, respectively.

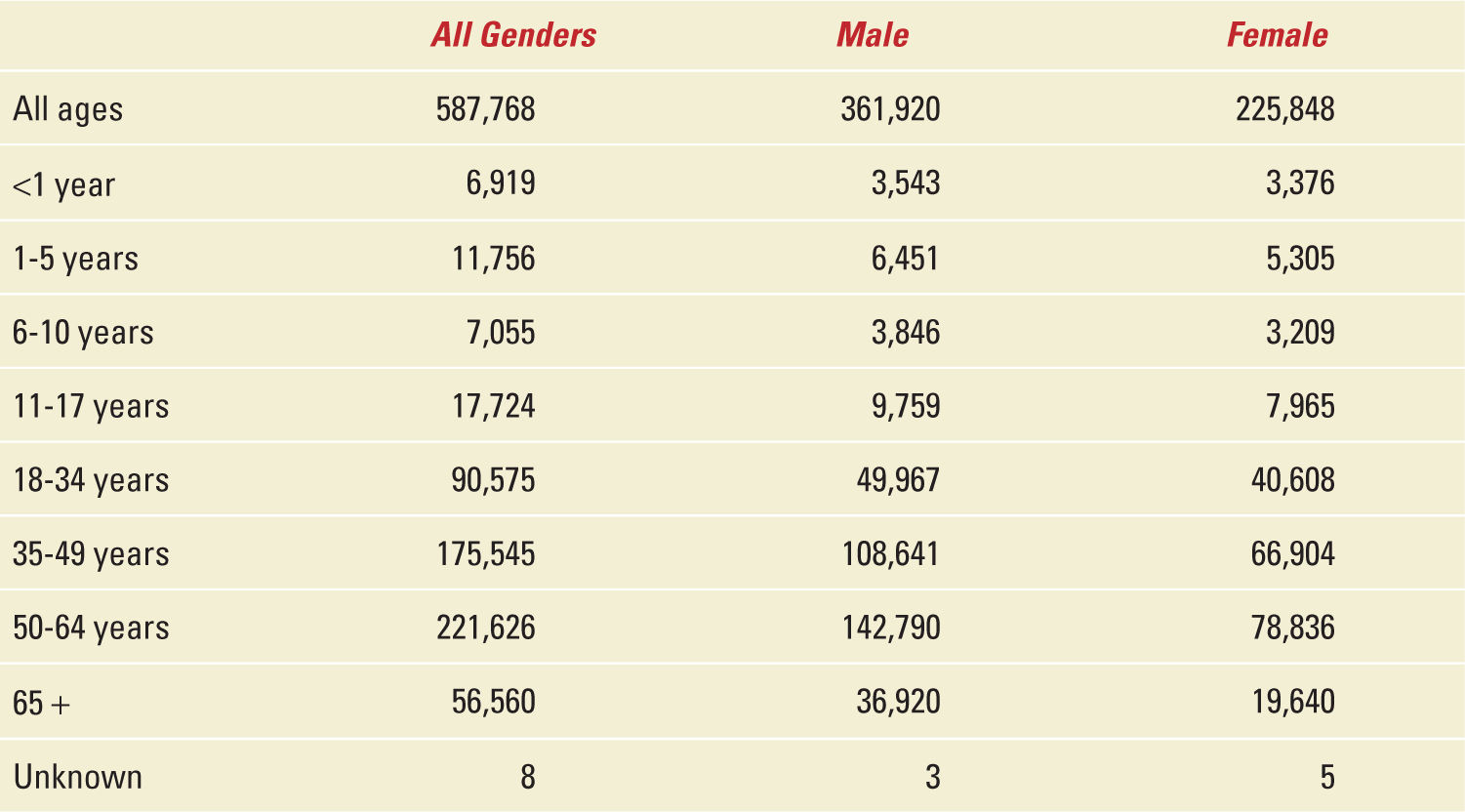

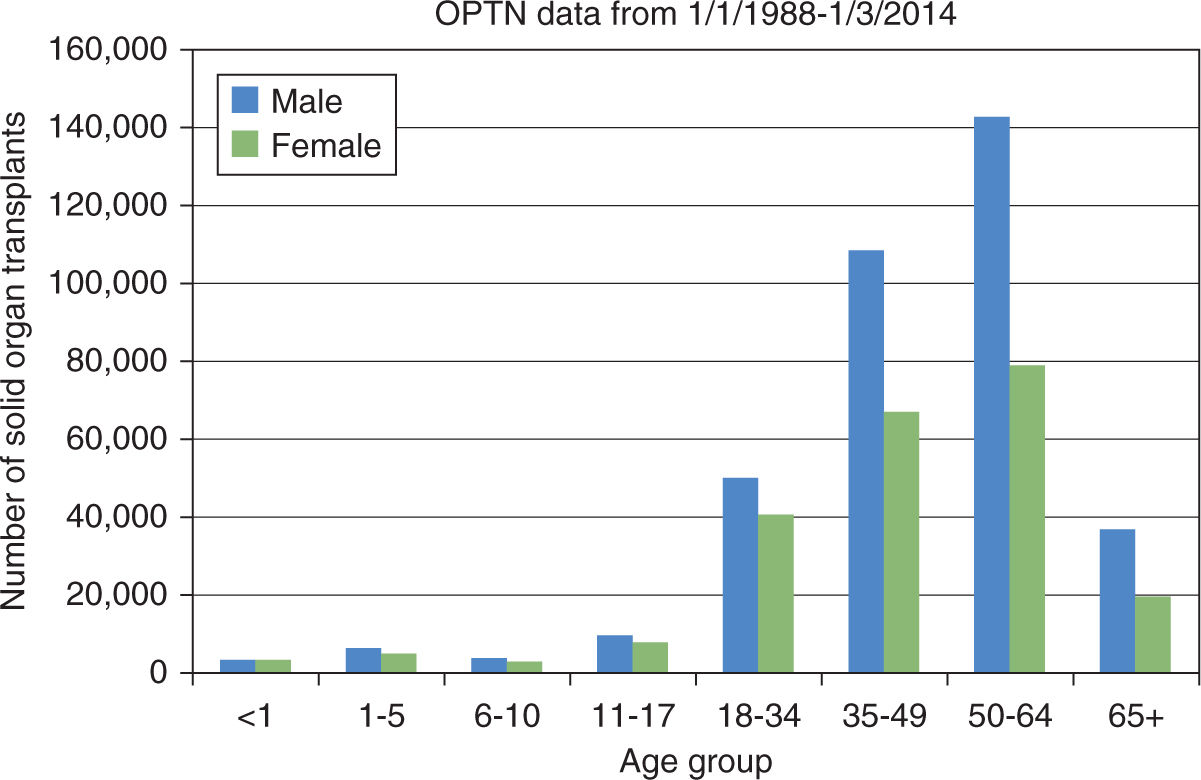

To better appreciate the scope of solid-organ transplantation in the United States, a brief overview of the governing body for transplantation is necessary. In 1984, the United States Congress under the National Organ Transplant Act created a unified transplant network for equitable organ allocation by enhancing the effectiveness and efficiency of organ sharing as well as making more donated organs available for transplantation through a unique public-private partnership of professionals comprising the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN). Today the OPTN keeps the only national patient waiting list which features the most comprehensive data available in any single field of medicine.1 Anyone can access this information and review the number of kidney, liver, pancreas, kidney-pancreas, heart, lung, heart-lung, and intestine transplants performed from 1988 to present. For example, on January 3, 2014, of nearly 600,000 solid-organ transplants performed in the United States, less than 40% were done in female patients of whom nearly 100,000 are of child-bearing age, see Table 34-1 and Figure 34-1.1 Other data gleaned from this website include total number of candidates on the waiting list, active candidates on the waiting list, number of transplants, and number of donors. For the sake of this chapter and because of its dependency on OPTN data, the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) and other datasets later mentioned over the course of this chapter, we will only refer to kidney, liver, heart, and lung transplantation. Because of the relatively small numbers of lung-transplantation procedures and few pregnancies after lung and heart-lung transplantation, we will combine heart-lung recipients with lung recipients in the lung transplantation cohort for simplicity. In view of so few reported pregnancies, there will be no mention of pregnancy after pancreas, intestinal, or other multiorgan transplant groups.

US Transplants Performed: Jan 1, 1988-Jan 3, 2014 |

FIGURE 34-1. Epidemiology of solid organ transplantation from 1988 to 2014.

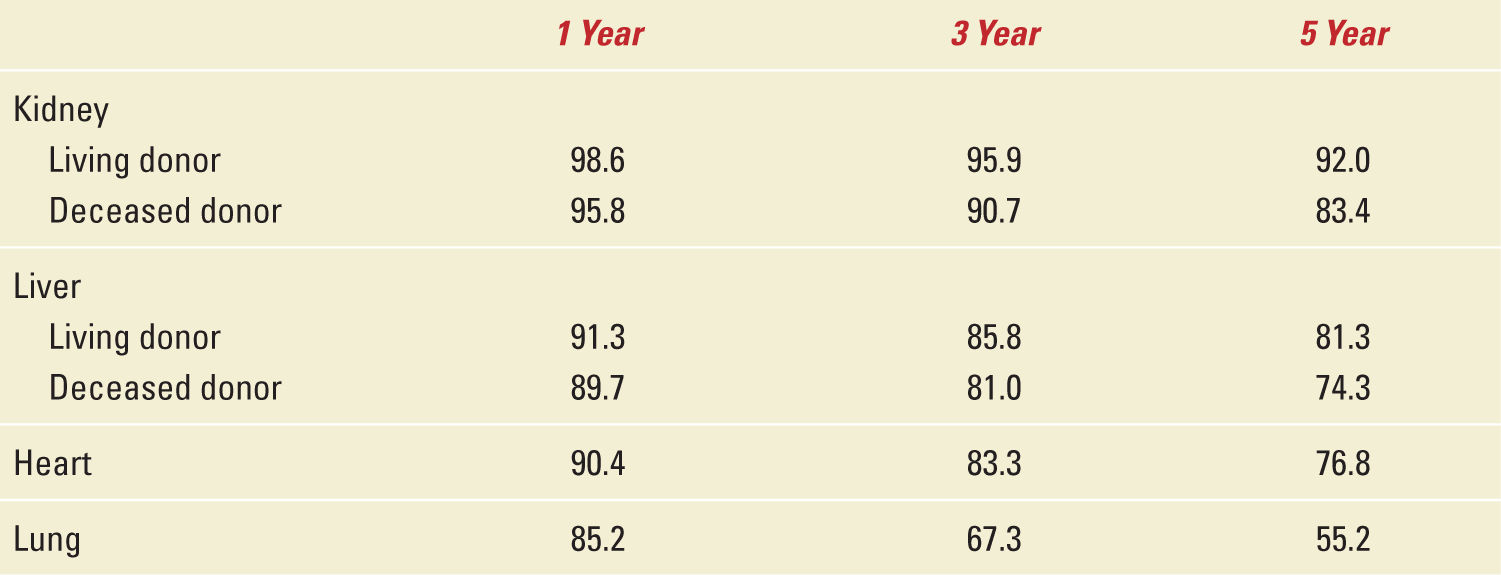

For six decades, solid organ transplantation has improved the longevity and overall quality of life for those afflicted with various chronic terminal and isolated end-organ diseases with survival rates up to 5 years as shown in Table 34-2 which was adapted from the last annual report of the OPTN/SRTR Data as of December 4, 2012.2 One outcome of transplantation has been the evolution of a “new” patient population in particular a group of young women previously rendered infertile because of their health problems who now find themselves able to bear children. As a direct result of organ replacement from transplantation, they are now able to lead a “normal” existence and feel relatively well especially with ovulatory cycles beginning as early as one month after transplantation.

Survival Rates after Transplantation (%) |

Pregnancy in the United States

To put things in perspective and to better understand some of the basic terminology related to pregnancy and fetal gestation alongside the evolution of transplantation over the last half-century, the annual number of United States births has ranged from 3.1 million in 1973 to a peak just over 4.3 million in 2007.3 However, there has been a consistent decline since 2007 to just under 4 million births in 2011. In this same time period, fertility rates (births per 1000 women aged 15-44) have declined by almost 50% from 118 in 1960 to the lowest ever reported at 63.2 in 2011.3 The preterm birth rate (less than 37 weeks of gestation) was 11.7%, and the early preterm rate (less than 34 weeks of gestation) was 3.4% from the final data of 2011. In this last report, 84% of the newborns weighed between 2500 and 3999 g (5 lb 9 oz-8 lb 3 oz). The rate of low birth weight (<2500 g) was 8.1%.3 The US neonatal mortality (deaths <28 days per 1000 live births) and infant mortality rates (deaths <1 year per 1000 live births) were 4.04 and 6.05, respectively, with congenital malformations, short gestation, and low birth weight accounting for 38% of all infant deaths.4 The last reported US pregnancy-related mortality rate in 2009 was 17.8 deaths per 100,000 live births with over 51.8% of the causes attributed to cardiovascular diseases including: cardiomyopathy, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy, thrombotic pulmonary embolism, and cerebrovascular accidents.5 Interestingly, of the 63.2 births per 1000 women in 2011 about half were unintended pregnancies. It has been reported that unintended pregnancies in the United States increase the risk for poor infant and maternal outcomes.6 Unplanned pregnancies after solid-organ transplantation have been reportedly as high as 90% from other countries.7

Solid-Organ Transplantation and Pregnancy in the United States

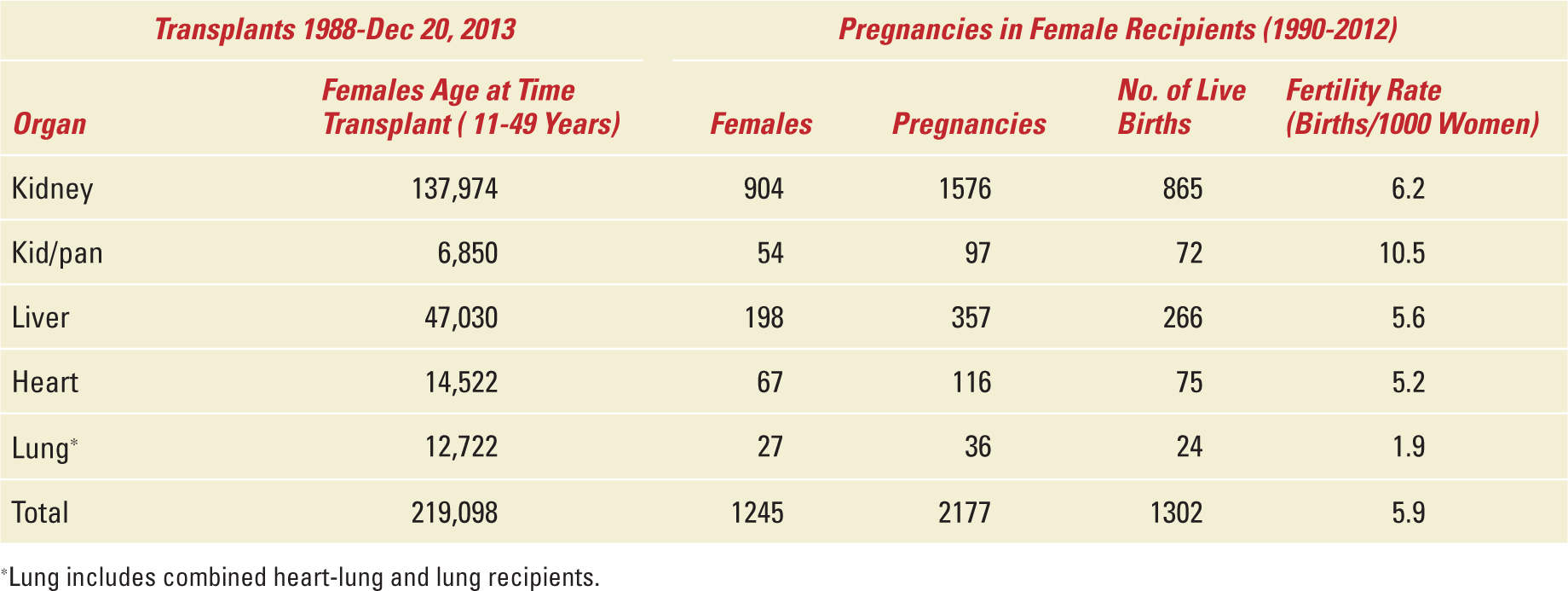

Within 5 years of the birth of solid-organ transplantation, the first child was born to a kidney-transplant recipient (KTR) on March 10, 1958. Since that time, over 14,000 pregnancies have been reported in female solid-organ recipients.8 Even though the first pregnancy was over half a century ago, and that pregnancy is not uncommon in transplant recipients, there was a paucity of information available to physicians and patients alike. To address these issues, the National Transplantation Pregnancy Registry (NTPR) was established in 1991 to study the safety of pregnancy and pregnancy outcomes for North American transplant recipients, the outcomes of pregnancies fathered by transplant recipients and the long-term implications of pregnancy on the recipient, allograft, and child.9 Other large international databases include the European Dialysis and Transplant Association Registry where data was collected between mid-1960 and 1992,10 and the UK Transplant Pregnancy Registry with data between 1994 and 2001.11 Cyclosporine revolutionized the field of transplantation and was started to be used widely in the mid-1980s. Hence, the NPTR better reflects and tracks results of pregnancy in modern day transplantation in terms of providing information for physicians and patients.12 Combining the data from the OPTN database (1) with the NPTR 2012 Annual Report12 allows us to calculate and estimate the fertility rates of female recipients in the United States as seen in Table 34-3. However, the fertility rates here were determined in female patients whose ages range from 11 to 49 years (perhaps reflecting a slightly older group who developed end-stage organ disease) as opposed to the 15- to 44-year-old healthy cohort from the US National Center of Health Statistics with a fertility rate of 63.2 births per 1000 women in 2011 as noted above. Other than kidney/pancreas recipients, the fertility rate of female solid-organ recipients is less than 10% of the overall US fertility rate of 63.2 in 2011. The total 5.9% fertility rate is underestimated by including female patients transplanted before 1990 and after 2012 as well as those aged 11 to 14 and 45 to 49 years at the time of transplant. However, this rate is overestimated, as some pregnancies have occurred in women transplanted before 1988. This estimate is further inflated by the lower survival rates of female solid-organ recipients relative to the normal population. Nevertheless, the live birth rates in this population are quite low and are lowest among female lung recipients. The fertility rate of 1.9% in this group is and quite likely much less than 3% of the 2011 US fertility rate reflecting the low median survival rate of around 7 years in women aged 11 to 49 after lung transplantation.13

Estimated Fertility Rates by Organ Group |

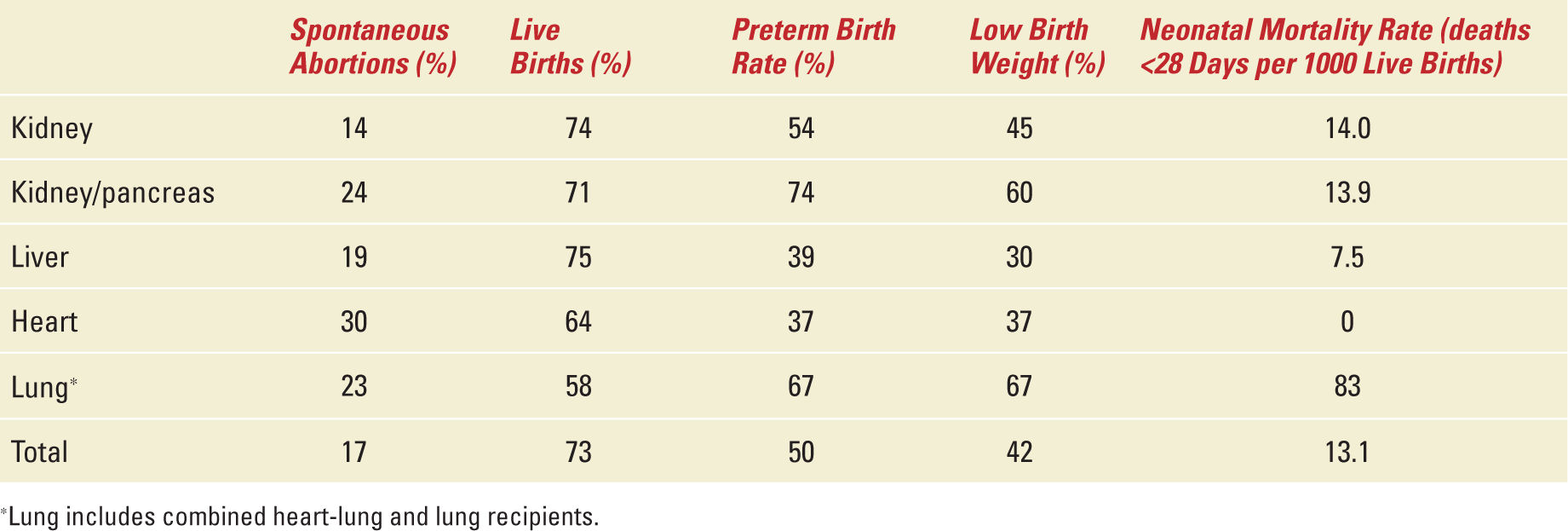

Table 34-4,12 adapted from the NTPR 2012 Annual Report provides a summary of the pregnancy outcomes in solid-organ recipients. Nearly 1/6 of pregnancies in female solid-organ recipients end in spontaneous abortions with the remaining 8% or so ending with a therapeutic abortion, an ectopic pregnancy or stillbirth. Three-quarters of these pregnancies result in live births ranging from 58% in lung to 75% in kidney and liver recipients. Half of these women have a short gestation period which is 4.5 times higher than the preterm birth rate of the normal US population. The low birth weight in 42% of the newborns of female solid-organ recipients is five times higher and the neonatal mortality rate is more than four times higher than in the US population (lowest in the liver recipients and 20 times higher in lung recipients).

Pregnancy Outcomes by Organ Group |

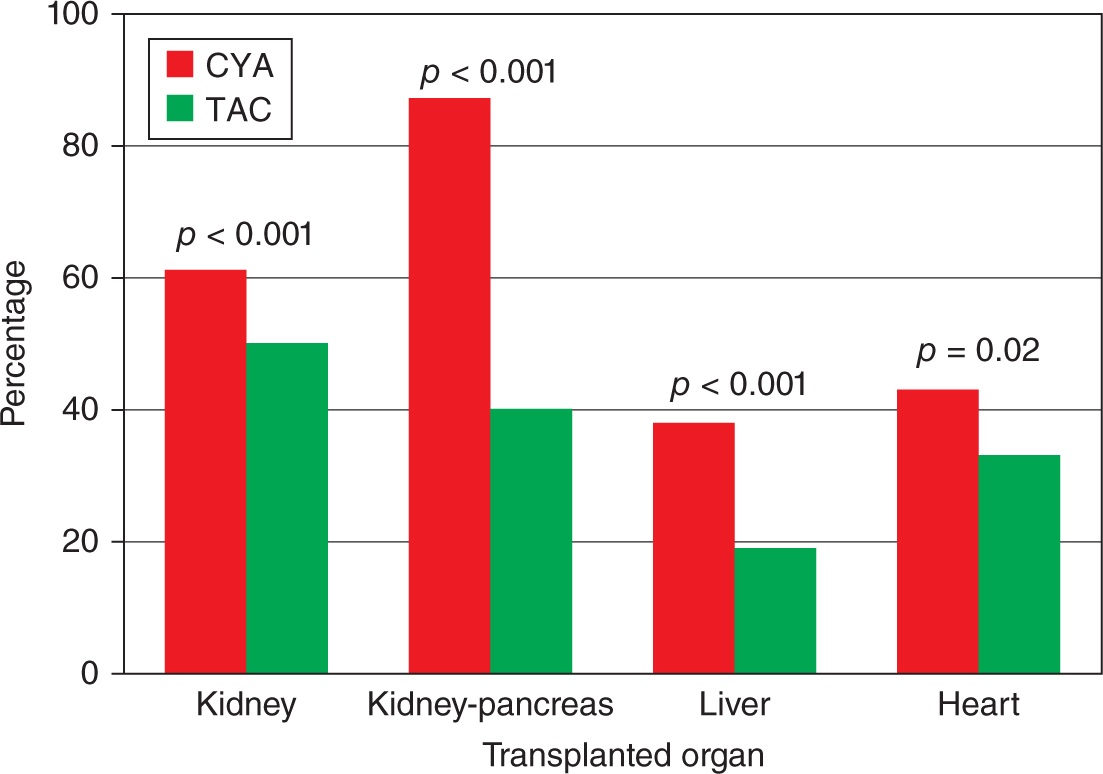

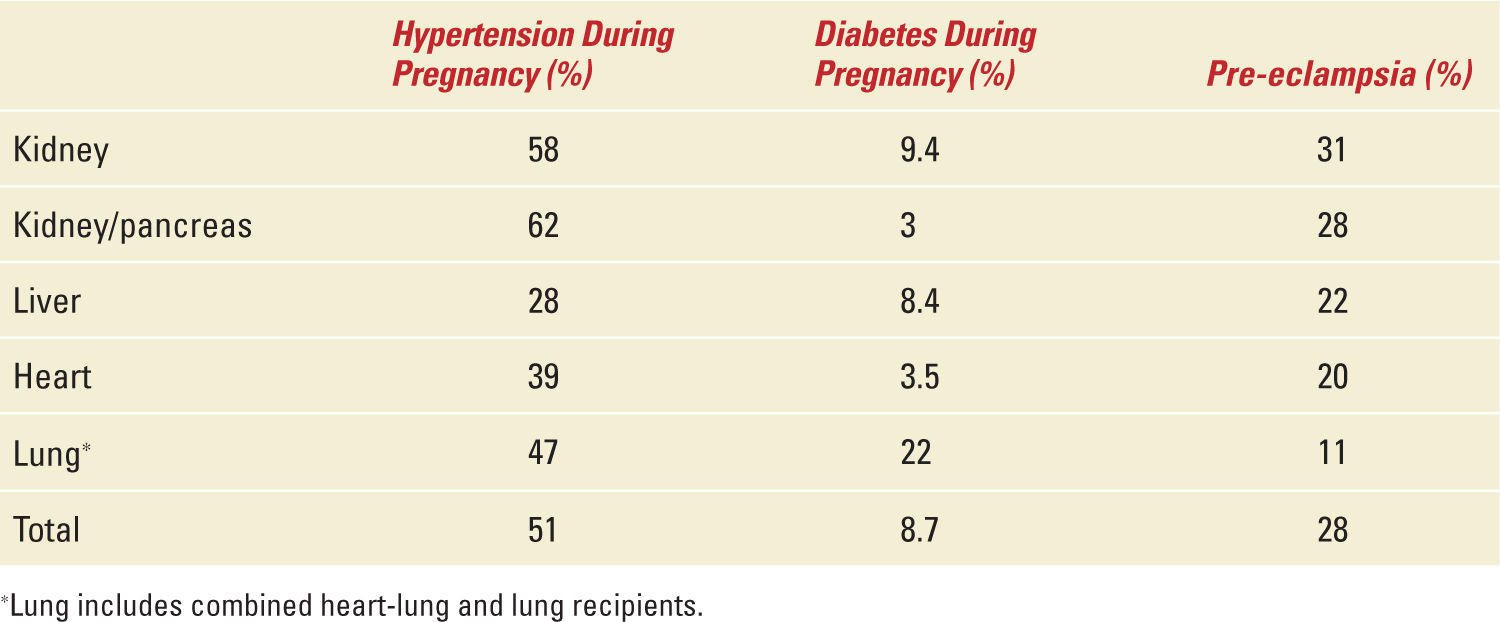

Table 34-5,12 that is another adaptation of NTPR, summarizes some of the important metabolic maternal outcomes with Figure 34-2 comparing the effect of cyclosporine and tacrolimus (the two important calcineurin inhibitors, CNIs, used for immunosuppression in transplant recipients) on hypertension observed during pregnancy. According to the information analyzed from the NTPR 2012 Annual Report,12 female recipients receiving tacrolimus during pregnancy were statistically less likely to have hypertension during pregnancy than those prescribed cyclosporine across all valuable groups by Chi-square analysis. Except for diabetes during pregnancy in the liver cohort, 15% in the tacrolimus group vs 1.2% in the cyclosporine group p value <0.001 by Fisher’s exact test, all other maternal complications comparing CNIs did not achieve statistical significance, data not shown. In general, tacrolimus is a safer CNI in female solid-organ recipients with respect to pregnancy and maternal outcomes.

FIGURE 34-2. Incidence of systemic hypertension in transplant recipients receiving cyclosporine or tacrolimus.

Maternal Outcomes (Metabolic) |

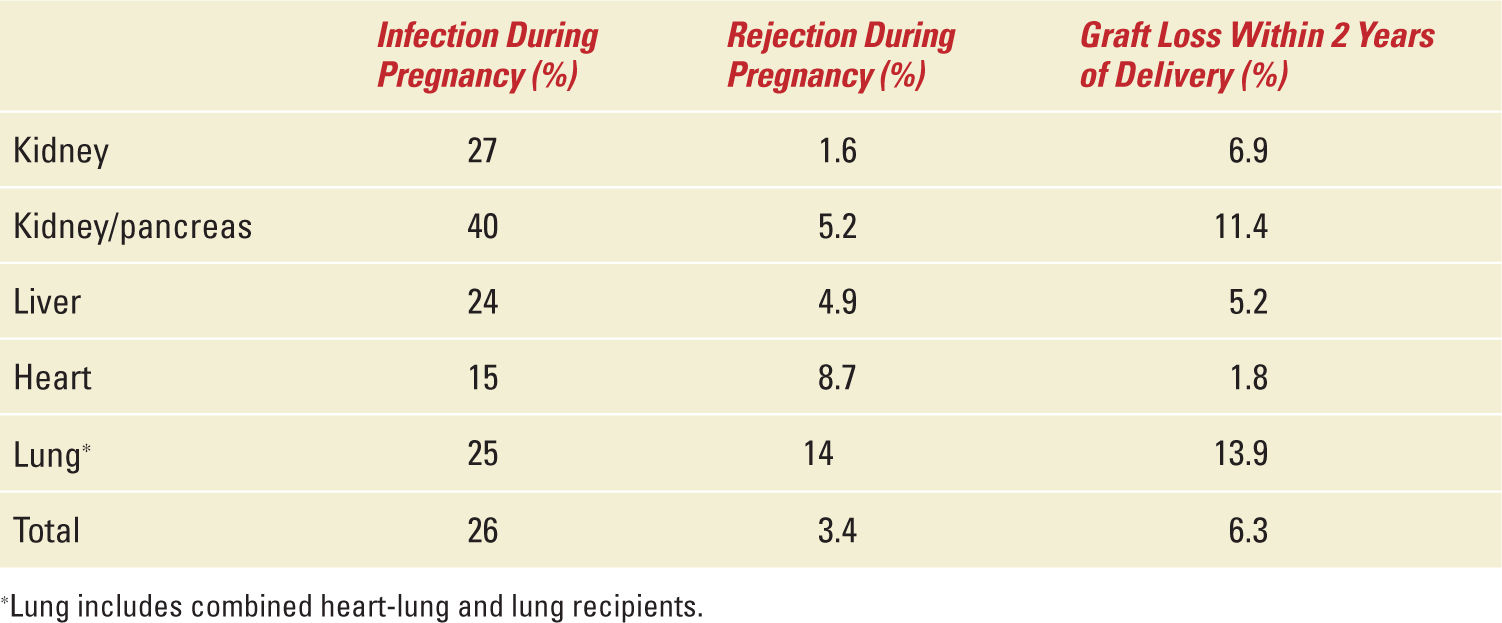

Table 34-6,12 also adapted from the NTPR Annual Report provides an immunologic snapshot of the maternal outcomes during and after pregnancy. Infection is more likely to occur than rejection during pregnancy. Allograft loss within 2 years of delivery has been reported in up to 14% of solid-organ recipients. This has grave implications in liver, heart, and lung recipients. The only alternative in these patients for survival is retransplantation. The pregnancy-related mortality rate in female solid-organ recipients remains unknown. The US pregnancy mortality rate is 17.8 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2009. The authors are aware of one death within the first year of delivery in a lung recipient yielding an estimated 4500 deaths/100,000 live birth pregnancy mortality rate in lung transplant women, personal experience. If this rate ever proves to be true, then female lung recipients are more than 250 times likely to die from a pregnancy-related death than normal American women.

Maternal Outcomes (Immunologic) |

Herein, all information described above from the aforementioned registries has been accumulated with pregnancy occurring in transplant recipients through times when effects on the mother, the fetus, and the newborn were largely unknown. Thereby, preconception counseling, pregnancy complications, prenatal and intrapartum considerations, outcomes by organ, immunosuppressant therapies, and neonatal outcomes were not addressed and if so not candid enough primarily from not knowing and without enough information. Obviously, pregnancy has occurred after transplantation, will continue to occur and likely increase in the future. Today, information from the NTPR is available to allow coordinators, physicians, surgeons, and other specialists to make reasonable and meaningful recommendations for safe and successful pregnancies. One important point is that during evaluation of potential candidates for transplantation, the pretransplantation period is the best time to address conception, pregnancy, and bringing a new life into the world along with the repercussions pregnancy has on solid-organ recipients and the child itself. For the remainder of this chapter, the topics will include some generalities, specifics about each of the transplant organ populations: kidney, liver, heart, and lung as well as special considerations with a summary and recommendations to assist in managing pregnancy after solid-organ transplantation.

GENERALITIES ON PREGNANCY AND SOLID-ORGAN TRANSPLANTATION

Ethical Issues

All solid-organ recipients not only have significant medical and surgical problems, but also have complicated medical regimens with immunosuppressive agents and other medications setting the stage for significant interactions and potential for fetal toxicities. More importantly, planning for pregnancy would be ideal, especially in the posttransplantation period with appropriate and important concerns regarding the status of the mother and necessary adjustments of the medications. Although there is not much written about the ethical issues surrounding pregnancy in transplant recipients and recognizing that at least half of the pregnancies are unintended, it is advisable that transplant specialists address these ethical issues with women of reproductive potential before transplantation. The potential risks and alternatives including adoption should be discussed. Women with transplants should understand the considerable probability of having a premature or preterm infant, one who is small for gestational age or one with congenital anomalies and that delivery by cesarean section might be necessary.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree