Toxoplasmosis

Nicole M. A. Le Saux

EPIDEMIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY

It is estimated that 500 million people worldwide are infected with Toxoplasma gondii.1 Seroprevalence studies have uniformly indicated increasing rates with age (eFig. 354.1  ). Between 1999 and 2004, the age-adjusted T. gondii seroprevalence rate declined from 14.1% to 9% among U.S.-born persons ages 12 to 49 years.2 Data from Europe generally indicates a slightly higher prevalence rate compared to the United States, with rates in Central Europe ranging from 24% in Greece to 41% in France and Poland.3-5 In the United States, seroprevalence rates in women of childbearing age are approximately 15%, whereas rates in similar populations from western Europe, Africa, and Central and South America are greater than 50%.1,6

). Between 1999 and 2004, the age-adjusted T. gondii seroprevalence rate declined from 14.1% to 9% among U.S.-born persons ages 12 to 49 years.2 Data from Europe generally indicates a slightly higher prevalence rate compared to the United States, with rates in Central Europe ranging from 24% in Greece to 41% in France and Poland.3-5 In the United States, seroprevalence rates in women of childbearing age are approximately 15%, whereas rates in similar populations from western Europe, Africa, and Central and South America are greater than 50%.1,6

Globally, infection rates primarily reflect soil temperatures—infection is much more common in warmer or temperate climates and is much less common in colder climates, such as in the northern hemispheres. Specific populations at risk included butchers and individuals of lower socioeconomic status.15,16

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

T. gondii is a parasite for which the members of the feline species (ie, cats, kittens, cougars) are the definitive hosts.18 Felines ingest the cyst form that is present in soil, which germinates in the cat’s small intestine and produces oocysts. The oocysts are then excreted in the feces for a period of 7 to 20 days into the surrounding environment. The oocyst can sporulate and become infective in the proper environmental conditions (such as warm soil). The oocyst does not sporulate below 4°C, which explains why colder climates would be inhospitable to sporulation. It is the sporulated oocyst that is infective when ingested by other mammals, including humans and other felines. The tachyzoite, which is the active proliferative form, develops from ingested sporulated oocysts. Within tissues and under the influence of the immune system, tachyzoites transform into bradyzoites, which exist within cysts as the latent form of infection. Although they can be present in any tissue, they are most numerous in the heart, brain, and skeletal muscle.

Humans either ingest infective sporulated oocysts or animal products containing tissue cysts. T. gondii invades and multiplies in the epithelial cells of the intestinal wall, releasing tachyzoites. The tachyzoite penetrates lymphatics and the bloodstream and disseminates to organs, where it invades cells, causing cell death, tissue necrosis, and an intense inflammatory response. Replication takes place rapidly until the host cell is disrupted, releasing more tachyzoites into contiguous tissues. The immune response to infection transforms the tachyzoites into bradyzoites, which multiply slowly and reside in tissue cysts, mainly in the brain and in skeletal and heart muscle, where the parasite survives in a latent form. In immunocompetent individuals, this chronic form generally has no adverse consequences. However, if subsequent immunosuppression occurs, especially impairment of cell-mediated immunity, bradyzoites can be released from cysts and can transform back into tachyzoites, causing recrudescence of infection.20

In North America and Europe, it is estimated that food-borne sources of toxoplasmosis are responsible for about 50% of infections.21,22 Food (pork, lamb, and their by-products such as salami, dried cured pork, or raw sausage) that has originated from animals infected with Toxoplasma are the principal sources.23 If food is eaten raw or undercooked, T. gondii cysts may remain viable and may infect the human host. Although freezing and cooking may kill tissue cysts, curing meat is not effective in killing them.24 In some circumstances, surface water contaminated with T. gondii enters the municipal water supply.27,28 In addition, contact with cats has been seen as a risk factor. Studies have shown that between 36% and 70% of infected persons recall contact with a cat.21,23,25,26 Other sources of transmission are blood or granulocyte transfusions, organ transplants, laboratory accidents, or transplacental infection from an infected mother.

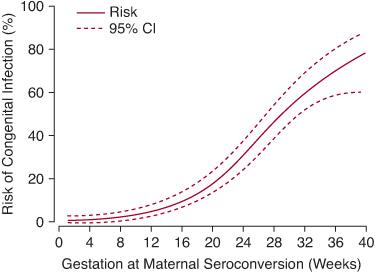

FIGURE 354-1. Risk of congenital infection by duration of gestation at the time of maternal infection. (From Dunn D, Wallon M, Peyron F, et al. Mother-to-child transmission of toxoplasmosis: risk estimates for clinical counselling. Lancet. 1999;353:1829-33.)

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS AND DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

The relatively benign nature of Toxoplasma gondii infection in healthy children belies its devastating effects when the disease is either acquired congenitally or reactivates in immunocompromised states. In immunocompetent hosts, most (90%) acute infections are sub-clinical or asymptomatic. If clinical symptoms do occur, the most common manifestation of primary acquired toxoplasmosis is enlarged lymph nodes, particularly in the cervical area. In some cases, this is accompanied by systemic, nonspecific symptoms such as malaise or low-grade fever. The differential diagnosis includes other systemic infections, including Epstein-Barr virus, cytomegalovirus, rubella virus, cat-scratch disease, tuberculosis, or malignancy. Other less common clinical presentations include myositis and myocarditis.30

Primary acquired Toxoplasma infection can also result in ocular lesions.32,33 It is now generally accepted that chorioretinitis can be a manifestation of recently acquired Toxoplasma infection.34 Recurrences of ocular toxoplasmosis, either from congenital or postnatal acquisition of disease, can occur over a period of years and is usually identified in the second through fourth decades of life.32,34,36

In immunocompromised patients, T. gondii infections can be of significant clinical consequence and are often fatal if not treated early. In these settings, infection is usually due to reactivation of a past infection. Patients at highest risk are those with a hematologic malignancy and those undergoing cytotoxic or immunosuppressive therapy. The incidence of Toxoplasma infection has dramatically decreased in those with HIV because of the widespread use of highly active antiretroviral therapy.

However, there are increasing reports of toxoplasmosis in those who have had organ transplants. The highest risk of reactivation occurs when the donor is seropositive and the recipient seronegative. The most common clinical presentations include encephalitis, pneumonia, retinochoroiditis, or myocarditis, but disseminated disease can also occur. Encephalitis may be subacute and may present with either nonspecific symptoms such as lethargy and changes in behavior or with focal neurological signs such as speech or visual difficulties, seizures, or other focal deficits. These will occasionally be accompanied by systemic signs such as fever or malaise.37–39 In heart transplant recipients, signs of rejection may mimic reactivation of toxoplasmosis in the transplanted organ. It has been suggested that seropositivity alone can be associated with increased mortality.40,41 Prophylaxis and early recognition in this special population are essential to ensure survival.

Congenital infections can occur when a mother acquires primary infection in the immediate preconception period or during gestation; rarely, the mother will experience a reactivation of Toxoplasma infection during gestation.42 The clinical manifestations in the offspring vary depending on the gestational age at the time of the acute maternal infection. Although the risk of transmission averages 29% (95% CI 25–33), the risk increases from 6% in the first trimester to 72% at 36 weeks gestation (Fig. 354-1).

Systematic screening studies have demonstrated that, of infants who have proven infection, up to 50% will have clinical signs that can only be detected with careful clinical examination; this suggests that subclinical disease is much more common than overt “classical” clinical manifestations.44,45 Infections in the first trimester of pregnancy are more likely to be associated with clinical signs compared to those that occur in the last trimester.43

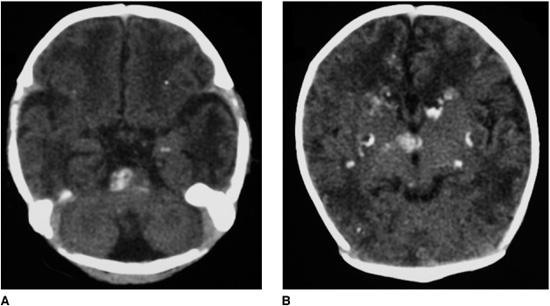

Neonates who are symptomatic at birth may present with neurological signs such as seizures, hydrocephalus, or microcephaly. Severe periaqueductal and periventricular vasculitis and necrosis (as evidenced by high levels of protein in the cerebrospinal fluid) cause the hydrocephalus typically seen with Toxoplasma cerebritis. Intracranial calcifications are usually seen on imaging studies of the brain47 (Fig. 354-2). Others may have retinochoroiditis or scars that can be seen only with fundoscopic examination. The differential diagnosis of neurological manifestations include other hereditary and infectious syndromes.48-51

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree