KEY POINTS

• The risk of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy and the puerperium is 0.5 to 2.0 per 1000 women, a four-to fivefold increase over the nonpregnant state.

• Women with genetic and acquired thrombophilias incur a higher risk of thrombosis during pregnancy.

• The risk for venous thromboembolism is approximately similar in all trimesters and postpartum; however, the risk of pulmonary embolism is highest postpartum and, in particular, following cesarean delivery.

• The treatment of venous thromboembolism during pregnancy is heparin based; with rare exceptions, warfarin derivatives are contraindicated in pregnancy but not during the puerperium or lactation.

VENOUS THROMBOEMBOLISM

Background

Definition

• Thromboses in the deep venous system or deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) are collectively known as venous thromboembolism (VTE). VTE occurs more frequently in pregnant women, with an incidence of 0.5 to 2.0 per 1000 pregnancies, roughly four to five times higher than in the nonpregnant population. The risk for VTE is further elevated in the postpartum period (1,2).

• Pulmonary emboli, which occur in less than 1 in 1000 pregnancies, cause about 10% of maternal deaths in the United States (3). Most PE in pregnancy originates from DVT. Other causes include fat, amniotic fluid, and air emboli.

Pathophysiology

• A combination of normal physiologic changes of pregnancy and external influences contributes to the increased risk of VTE by altering all three components of the Virchow triad.

• Hormone-related increases in the hepatic synthesis of components of the clotting cascade: fibrinogen, prothrombin, and factors VII, VIII, IX, and X. In the postpartum period, concentrations of factors V, VII, and IX are further elevated.

• Relative stasis of flow in the venous circulation, particularly in late pregnancy due to compression of the inferior vena cava by the expanding uterus.

• Endothelial injury, most often occurring at delivery and particularly after operative delivery. Medical complications of pregnancy associated with endothelial dysfunction (e.g., preeclampsia) may also increase the risk of VTE.

Epidemiology

• Risk factors for VTE in pregnancy (2,4)

• Patient characteristics: age greater than 35 years, parity ≥3, African American race, positive family history (first-degree relatives)

• Medical conditions: heart disease, blood disorders including sickle cell disease, autoimmune disorders including lupus and antiphospholipid syndrome, hypertension, diabetes, inflammatory bowel disease

• Obesity

• History of superficial thrombophlebitis (STP), varicose veins

• Smoking

• Surgery in pregnancy

• Complications of pregnancy:

Assisted reproduction, multiple gestation, hyperemesis, urinary tract infection, diabetes, antepartum hemorrhage, anemia

Assisted reproduction, multiple gestation, hyperemesis, urinary tract infection, diabetes, antepartum hemorrhage, anemia

• Peripartum complications:

Preeclampsia, stillbirth

Preeclampsia, stillbirth

• Complications of delivery and the puerperium:

Cesarean delivery (especially emergency cesarean delivery), postpartum infection, postpartum hemorrhage, transfusion

Cesarean delivery (especially emergency cesarean delivery), postpartum infection, postpartum hemorrhage, transfusion

Evaluation

History and Physical

• STP may present with inflammation, local edema, and pain, commonly at intravenous (IV) catheter sites.

• DVT is associated with pain, erythema, and edema, and most commonly occurs in a lower extremity.

• The physical findings include tenderness to palpation of the involved extremity and asymmetric edema resulting in unequal calf circumferences (discrepancy of greater than 2 cm). DVT is more common in the left lower extremity, presumably due to relative compression of the left common iliac vein by the right common iliac artery.

• Homans sign (calf tenderness on dorsiflexion of the foot) is neither sensitive nor specific for DVT in pregnancy, as most DVT in pregnancy occurs in the iliofemoral system.

• PE may present with dyspnea, substernal or pleuritic chest pain, tachypnea, apprehension, and cough.

• Significant emboli may present with cardiovascular collapse, shock, and/or death.

• Signs include tachycardia, jugular venous distension, parasternal heave, rales, hemoptysis, fever, diaphoresis, a pleural rub, and an S3 murmur.

Laboratory Tests

• In pregnant women suspected of having a PE, the laboratory testing may include

• Arterial blood gases:

Usually reveal arterial hypoxemia (PaO2 less than 70 mm Hg) without hypercarbia (normal PaCO2 in pregnancy = 28 to 32 mm Hg) or an increased alveolar–arterial oxygen gradient (greater than 15).

Usually reveal arterial hypoxemia (PaO2 less than 70 mm Hg) without hypercarbia (normal PaCO2 in pregnancy = 28 to 32 mm Hg) or an increased alveolar–arterial oxygen gradient (greater than 15).

PE is unlikely if the PaO2 is greater than 85 mm Hg.

PE is unlikely if the PaO2 is greater than 85 mm Hg.

• D-dimer is a degradation product formed during the lysis of fibrin by plasmin.

D-dimer concentrations (measured by ELISA) of less than 500 μg/mL in nonpregnant individuals essentially exclude PE (posttest probability less than 5%) (5).

D-dimer concentrations (measured by ELISA) of less than 500 μg/mL in nonpregnant individuals essentially exclude PE (posttest probability less than 5%) (5).

D-dimer concentrations are normally increased in pregnancy. Cases of DVT and PE have been reported with negative D-dimer levels; consequently, D-dimers should not be used to exclude DVT and PE in pregnancy (6).

D-dimer concentrations are normally increased in pregnancy. Cases of DVT and PE have been reported with negative D-dimer levels; consequently, D-dimers should not be used to exclude DVT and PE in pregnancy (6).

Genetics

• Hereditary thrombophilia (one or more) will be identified in at least 20% to 50% of women who experience VTE during pregnancy (2).

• Testing for hereditary thrombophilia is appropriate in women with a history of VTE, as results of testing may affect the thromboprophylactic regimen (1).

• General population screening for thrombophilia is not recommended, as the prevalence of some of these conditions is high, but the absolute risk of thromboembolism is low (7).

• Thrombophilias are discussed elsewhere in this chapter.

Diagnosis

Clinical Manifestations

• STP is diagnosed by physical examination, which will demonstrate inflammation and tenderness, and often a palpable thrombus.

• The clinical suspicion of DVT generally requires confirmation by imaging.

Imaging Techniques

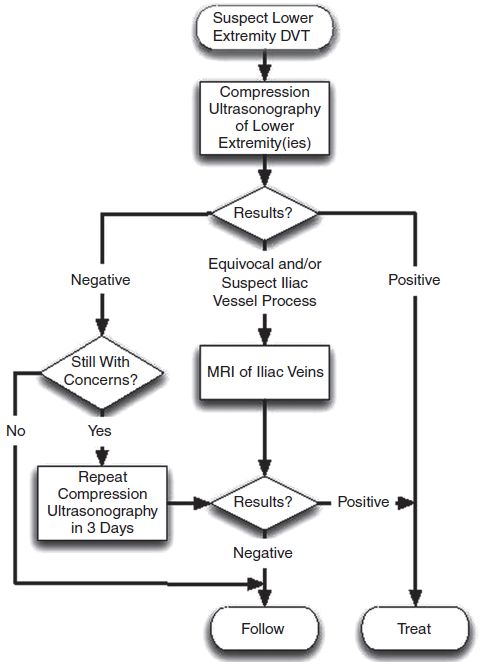

• The diagnosis of DVT may be confirmed by a variety of imaging modalities (1,6).

• Venous ultrasonography has a 95% sensitivity and 96% specificity for the diagnosis of symptomatic proximal DVT in the general population. However, it is less accurate for calf and iliac vein thrombosis (8). Due to the high proportion of DVT occurring above the inguinal ligament, accuracy of ultrasound is likely reduced during pregnancy. Two components of venous ultrasound are utilized in this imaging modality:

Compression ultrasound: The presence of a thrombus prevents coaptation of the vein walls.

Compression ultrasound: The presence of a thrombus prevents coaptation of the vein walls.

Duplex Doppler ultrasound: The absence of venous flow in the femoral system as measured by Doppler techniques indicates a proximal occlusion. This is valuable for assessing for the presence of iliac thrombosis. Color Doppler imaging may further enhance the value of this modality.

Duplex Doppler ultrasound: The absence of venous flow in the femoral system as measured by Doppler techniques indicates a proximal occlusion. This is valuable for assessing for the presence of iliac thrombosis. Color Doppler imaging may further enhance the value of this modality.

• Occasionally, additional imaging may be required such as magnetic resonance venography or magnetic resonance direct thrombus imaging (Fig. 22-1) (1).

• A number of imaging tests used in the evaluation of the patient with suspected of PE involve radiation exposure for the fetus. The total fetal radiation exposure in a woman requiring chest radiography, ventilation/perfusion ( /

/ ) imaging, and pulmonary angiography is estimated as 0.5 rad (5 mGy), substantially lower than the 1.0-rad exposure (10 mGy) threshold thought to increase slightly the risk of childhood malignancies (9). These tests should never be withheld in a pregnant woman suspected to have pulmonary thromboembolism, given the mortality of this condition.

) imaging, and pulmonary angiography is estimated as 0.5 rad (5 mGy), substantially lower than the 1.0-rad exposure (10 mGy) threshold thought to increase slightly the risk of childhood malignancies (9). These tests should never be withheld in a pregnant woman suspected to have pulmonary thromboembolism, given the mortality of this condition.

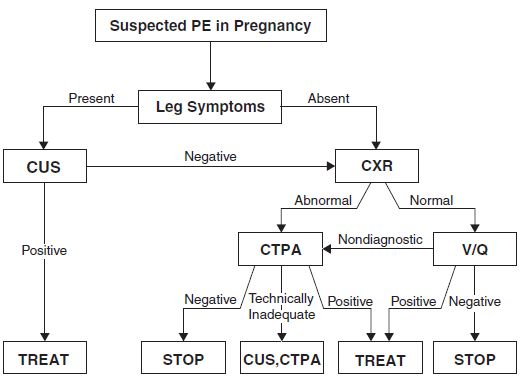

• Chest radiography will demonstrate vascular congestion, elevation of the hemidiaphragm, atelectasis, and pulmonary edema in up to 70% of patients with PE and will exclude pneumonia as an alternate diagnosis. Chest radiography results in less than 0.001 rad fetal radiation per exposure (less than 0.01 mGy) (9).

• Electrocardiography may show tachycardia. The classic findings of acute cor pulmonale (right axis deviation with S1Q3T3 and nonspecific T-wave inversion) usually are seen only in massive PE.

• Ventilation/perfusion ( /

/ ) scan results in a fetal radiation exposure of 0.1 to 0.37 mGy (9).

) scan results in a fetal radiation exposure of 0.1 to 0.37 mGy (9).

A

A  /

/ scan or perfusion scan alone should be performed next if the chest radiograph is normal (6) (a normal perfusion scan essentially excludes PE, and the additional imaging time and radiation exposure of the ventilation phase can be avoided.)

scan or perfusion scan alone should be performed next if the chest radiograph is normal (6) (a normal perfusion scan essentially excludes PE, and the additional imaging time and radiation exposure of the ventilation phase can be avoided.)

The presence of a

The presence of a  /

/ mismatch is very reliable for diagnosing PE in pregnancy (6).

mismatch is very reliable for diagnosing PE in pregnancy (6).

Matching

Matching  /

/ defects may be seen in women with underlying pulmonary disease, and angiography may be necessary to diagnose or exclude PE.

defects may be seen in women with underlying pulmonary disease, and angiography may be necessary to diagnose or exclude PE.

The primary reason to choose

The primary reason to choose  /

/ scan over computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA) is the increased radiation exposure to maternal breast tissue with CTPA (approximately a four- to eightfold increase) (6).

scan over computed tomographic pulmonary angiography (CTPA) is the increased radiation exposure to maternal breast tissue with CTPA (approximately a four- to eightfold increase) (6).

• CTPA is the diagnostic test of choice if the chest radiograph is abnormal or unavailable (6) (and has become the first-line imaging test for PE in many institutions). Fetal radiation exposure is estimated at 0.006 to 0.096 rad per procedure (0.06 to 0.96 mGy) (9).

CTPA may be considered diagnostic (posttest probability greater than 85%) when positive and exclusionary (posttest probability less than 1%; negative predictive value ~99%) when negative.

CTPA may be considered diagnostic (posttest probability greater than 85%) when positive and exclusionary (posttest probability less than 1%; negative predictive value ~99%) when negative.

If venous ultrasonography or additional imaging studies are abnormal, treatment for DVT should be initiated (Fig. 22-2).

If venous ultrasonography or additional imaging studies are abnormal, treatment for DVT should be initiated (Fig. 22-2).

Figure 22-1. Recommended algorithm for evaluation of the pregnant patient with suspected deep venous thrombosis.

Figure 22-2. ATS/STR diagnostic algorithm for suspected PE in pregnancy. (Reprinted with permission of the American Thoracic Society. Copyright © 2013 American Thoracic Society. From Leung AN, Bull TM, Jaeschke R, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/Society of Thoracic Radiology clinical practice guideline: evaluation of suspected pulmonary embolism in pregnancy. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2011;184(10):1200–1208. Official Journal of the American Thoracic Society.)

Differential Diagnosis

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree