KEY POINTS

• At least one person qualified to perform neonatal resuscitation should be in attendance at every delivery.

• Anticipation and preparation are critical for a smooth, successful resuscitation.

• The key characteristics for determining the need for further resuscitation after the initial steps of stabilization are respirations and heart rate.

• The most important and effective action in neonatal resuscitation is to ventilate the infant’s lungs with blended air.

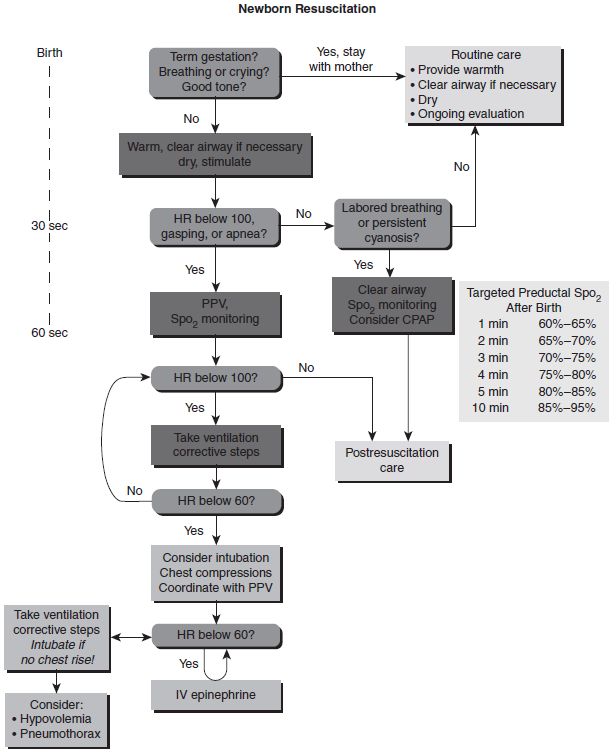

• The steps of evaluation, decision, and action outlined in the algorithm of resuscitation of the newborn infant should be followed to ensure optimal neonatal resuscitation.

• Not initiating or discontinuing neonatal resuscitation may be appropriate in certain circumstances.

BACKGROUND

Definition

Hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy (HIE) usually involves a complex combination of hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and circulatory insufficiency that may be induced by a variety of perinatal events.

Pathophysiology

Physiologic Changes During Hypoxia

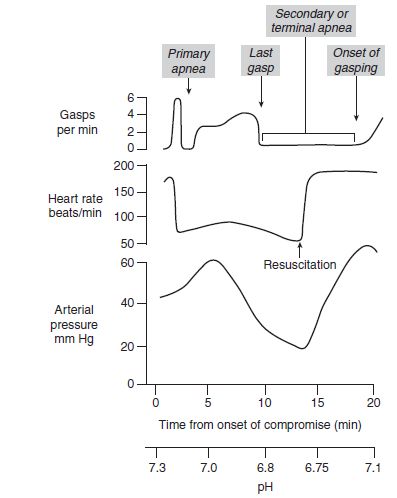

• The events that occur during hypoxia in the human newborn probably are analogous to those that occur in the fetal primate model described by Dawes (1) (Fig. 38-1):

• The initial brief response to hypoxia is one of hypertension and hypercapnia.

• A period of primary apnea then occurs, followed by gasping in an effort to establish respirations.

• If there is no reversal of the hypoxia, the fetus enters a phase of secondary apnea, bradycardia, and shock.

• At this point, central nervous system and multisystem organ damage begins to occur. If resuscitative measures are not initiated, the infant will die.

• Decreased central nervous system blood flow and hypoxemia may lead to cerebral edema and hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Further neurologic injury also may occur as the result of hemorrhage in ischemic and damaged portions of the brain.

Figure 38-1. Sequence of physiologic events in animal models from multiple species involving complete total asphyxia. Note the prompt increase in heart rate as soon as resuscitation has begun. (Used with permission of the American Academy of Pediatrics. Textbook of neonatal resuscitation. 6th ed. American Academy of Pediatrics and American Heart Association, 2011.)

• Primary and secondary apnea cannot be easily distinguished in the clinical setting. Therefore, any apnea at birth is assumed to be secondary apnea, and neonatal resuscitation should be initiated as taught in the American Heart Association–American Academy of Pediatrics Neonatal Resuscitation Program (NRP) (2).

Etiology

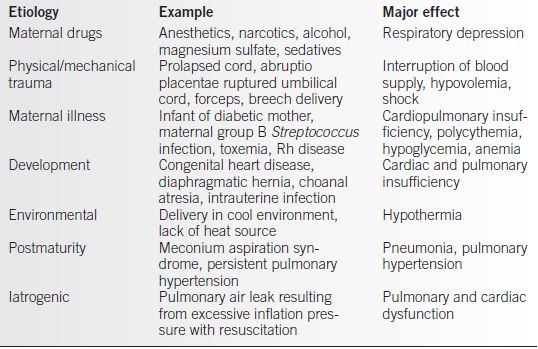

Although the causes of neonatal cardiopulmonary depression and hypoxia are often unknown, many causes have been identified, including drugs, trauma, hemorrhage, developmental anomalies, infection, and iatrogenic causes. Some of the common causes of neonatal hypoxia ischemia are summarized in Table 38-1.

Table 38-1 Causes of Neonatal Cardiorespiratory Depression and Hypoxia

Epidemiology

Many newborn infants may experience some degree of cardiorespiratory depression, characterized by a heart rate less than 100 beats/min (bpm), some degree of hypotension, and hypoventilation and/or apnea in the delivery room. However, true intrapartum hypoxia occurs in approximately 1.5 per 1000 term live births (3). HIE has a worldwide mortality of 10% to 60% of affected infants, and approximately 25% of survivors have long-term neurodevelopmental delay (4).

TREATMENT

Goal of Resuscitation

• The aim of a successful resuscitation should be the immediate reversal of hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and circulatory insufficiency to prevent permanent damage to the central nervous system or other organs. This can be accomplished by means that are directed at

• Reducing oxygen consumption by drying the infant and conducting the resuscitation on a radiant warmer

• Clearing the airway of secretions, meconium, and other material

• Performing effective positive-pressure ventilation (PPV)

• Maintaining adequate perfusion to the vital organs

Procedures

The following discussion is a summary of the guidelines of the American Heart Association– American Academy of Pediatrics NRP based on the Textbook of Neonatal Resuscitation, sixth edition (2).

Principles of Successful Resuscitation

• Anticipation.

• Good communication between the care providers for the mother and the neonatal resuscitation team is critical:

Pertinent information in the perinatal history that may affect the infant should be disclosed.

Pertinent information in the perinatal history that may affect the infant should be disclosed.

A review of the mother’s medical chart and medication record is recommended before delivery if possible.

A review of the mother’s medical chart and medication record is recommended before delivery if possible.

• A successful resuscitation depends on

Anticipating a clinical situation likely to require neonatal resuscitation

Anticipating a clinical situation likely to require neonatal resuscitation

Having a skilled team available to respond to a compromised infant

Having a skilled team available to respond to a compromised infant

• Personnel.

• At least one person demonstrating competence at neonatal resuscitation, preferably with NRP certification, should be present at every delivery.

• If the newborn is severely depressed, there should be at least two people at the resuscitation:

One person to ventilate and intubate if necessary

One person to ventilate and intubate if necessary

A second person to monitor the heart rate and perform chest compressions if needed

A second person to monitor the heart rate and perform chest compressions if needed

• If prolonged resuscitation is required, a team of three or more people is recommended.

• The resuscitation team members must not only know what tasks to perform but must be able to perform these tasks efficiently and effectively.

• Equipment and preparation.

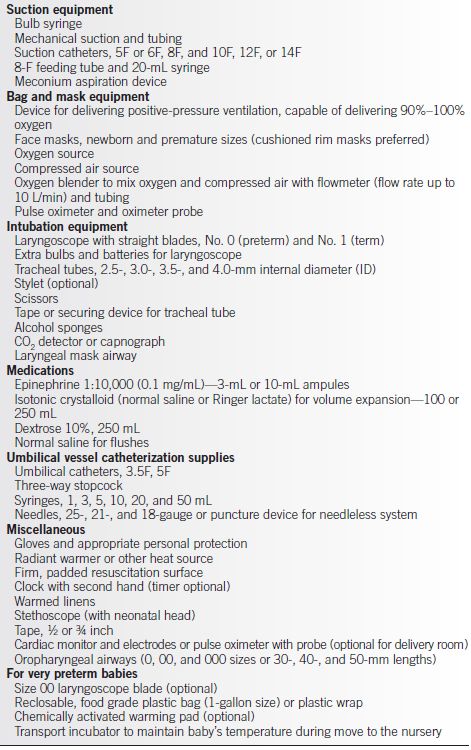

• Appropriate resuscitation equipment and medications must be immediately available, and equipment must be in working order (Table 38-2).

• If there is enough time before delivery, the resuscitation team should

Check the equipment to make sure it is functioning properly.

Check the equipment to make sure it is functioning properly.

Ensure blended oxygen and suction are available.

Ensure blended oxygen and suction are available.

Ensure ample heat (radiant warmer) is available.

Ensure ample heat (radiant warmer) is available.

Draw up medications if appropriate.

Draw up medications if appropriate.

Introduce themselves to the parents, and explain the procedures to be completed and the difficulties that may be expected.

Introduce themselves to the parents, and explain the procedures to be completed and the difficulties that may be expected.

• Universal precautions should be followed because blood and other body fluid exposures are possible in the delivery room.

• The ABCs of resuscitation should be followed.

• Airway

Establish an open airway by positioning the infant to maximize the airway.

Establish an open airway by positioning the infant to maximize the airway.

Suction the mouth, nose, and, in some cases, the trachea to ensure an open airway.

Suction the mouth, nose, and, in some cases, the trachea to ensure an open airway.

Endotracheal tube (ETT) intubation may be necessary to ensure a patent airway in some situations.

Endotracheal tube (ETT) intubation may be necessary to ensure a patent airway in some situations.

• Breathing

Breathing can be stimulated by tactile stimulation (optional).

Breathing can be stimulated by tactile stimulation (optional).

If necessary, PPV may be administered via a bag and mask, a T-piece device, or an ETT.

If necessary, PPV may be administered via a bag and mask, a T-piece device, or an ETT.

• Circulation

Stimulate and maintain circulation of blood with chest compressions, fluids, or drugs when indicated.

Stimulate and maintain circulation of blood with chest compressions, fluids, or drugs when indicated.

Initial Steps in Resuscitation

• Initial evaluation.

• Within a few seconds of life, the initial assessment of the newborn should be performed and the need for routine care or further neonatal resuscitation determined.

• The algorithm (Fig. 38-2) shows the steps of evaluation, decision, and action.

• The resuscitator should rely on respiratory effort, heart rate, and color to evaluate the infant’s condition. If, as a result of assessing these signs, the infant is determined to be in distress, the resuscitator should initiate measures long before the 1-minute Apgar score is assigned.

Table 38-2 Neonatal Resuscitation Supplies and Equipment

Used with permission of the American Academy of Pediatrics, Textbook of Neonatal Resuscitation, 6th edition, copyright American Academy of Pediatrics and American Heart Association, 2011.

Figure 38-2. Algorithm for resuscitation of the newborn. (Reproduced from Kattwinkel J, et al. Part 15: neonatal resuscitation: 2010 American Heart Association Guidelines for cardiopulmonary resuscitation and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation. 2010;122:S909–S919, with permission.)

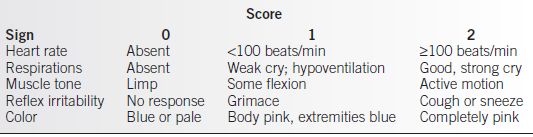

• The Apgar scores (Table 38-3) should be obtained at 1 minute and 5 minutes after birth:

The Apgar score is not used to determine when to initiate resuscitation or to determine what course of action to take during resuscitation.

The Apgar score is not used to determine when to initiate resuscitation or to determine what course of action to take during resuscitation.

When the 5-minute Apgar is less than 7, Apgar scores should be assigned every 5 minutes for up to 20 minutes or until the score is ≥7.

When the 5-minute Apgar is less than 7, Apgar scores should be assigned every 5 minutes for up to 20 minutes or until the score is ≥7.

The Apgar score at 5 and 10 minutes is a useful component in predicting acute multisystem organ dysfunction.

The Apgar score at 5 and 10 minutes is a useful component in predicting acute multisystem organ dysfunction.

Table 38-3 Apgar Score

• Initial steps of the resuscitation process should take no more than a few seconds to accomplish and include the following:

• Warmth.

Place the infant on an overhead radiant heater.

Place the infant on an overhead radiant heater.

Dry the infant thoroughly with preheated towels or blankets.

Dry the infant thoroughly with preheated towels or blankets.

Remove the wet towels to prevent heat loss.

Remove the wet towels to prevent heat loss.

Perinatal hyperthermia (greater than 36.5°C–37°C) should be avoided.

Perinatal hyperthermia (greater than 36.5°C–37°C) should be avoided.

Therapeutic hypothermia is currently recommended for neonates ≥36 weeks with evidence of moderate/severe HIE (5).

Therapeutic hypothermia is currently recommended for neonates ≥36 weeks with evidence of moderate/severe HIE (5).

• Position the infant and clear the airway:

Place the infant on the back or side with the head slightly extended in the neutral position (“sniffing” position).

Place the infant on the back or side with the head slightly extended in the neutral position (“sniffing” position).

Suction the mouth and nose to clear the airway.

Suction the mouth and nose to clear the airway.

The mouth should be suctioned first with a bulb syringe to decrease the risk of aspiration, and then the nose is subsequently suctioned.

The mouth should be suctioned first with a bulb syringe to decrease the risk of aspiration, and then the nose is subsequently suctioned.

A shoulder roll consisting of a rolled towel or blanket may be used to elevate the shoulders slightly.

A shoulder roll consisting of a rolled towel or blanket may be used to elevate the shoulders slightly.

If large amounts of secretions are coming from the mouth, the infant’s head may be turned to the side to facilitate removal of these secretions.

If large amounts of secretions are coming from the mouth, the infant’s head may be turned to the side to facilitate removal of these secretions.

• Initiation of breathing.

The infant may be stimulated by both drying and suctioning.

The infant may be stimulated by both drying and suctioning.

However, if the infant does not breathe immediately, slapping or flicking the soles of the feet or rubbing the infant’s back with a warm blanket is an optional method to stimulate breathing. Other methods of infant stimulation are not recommended and may be harmful.

However, if the infant does not breathe immediately, slapping or flicking the soles of the feet or rubbing the infant’s back with a warm blanket is an optional method to stimulate breathing. Other methods of infant stimulation are not recommended and may be harmful.

If there is no response to tactile stimulation within a few seconds, PPV should begin.

If there is no response to tactile stimulation within a few seconds, PPV should begin.

• Continued assessment is the next step in the resuscitative process and involves evaluating the infant’s respiratory efforts, heart rate, and color to determine further action:

• If the infant is apneic or gasping, PPV should be initiated with bag and mask and blended oxygen. If there is adequate respiratory effort, the infant’s heart rate should be evaluated.

• If the heart rate is greater than 100 bpm, the infant’s color should be evaluated. If the heart rate is less than 100 bpm, PPV must be initiated. Continued monitoring of the heart rate will determine whether chest compressions or medication is indicated.

• If central cyanosis is persistent despite blended oxygen, PPV should be initiated.

• In summary, if the infant is apneic, is gasping, or has inadequate respirations or the heart rate is less than 100 bpm, PPV must be initiated immediately to ensure adequate oxygenation.

• The administration of blended oxygen alone or persistent efforts to provide tactile stimulation to a nonbreathing infant or one whose heart rate is less than 100 bpm is of no value, delays appropriate management, and increases the risk of central nervous system and other organ damage.

Positive-Pressure Ventilation

• Adequate ventilation must be established for neonatal resuscitation to be successful.

• The equipment required for PPV should be available in the delivery room at all times and includes

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree