KEY POINTS

• Labor and delivery are normal physiologic processes.

• Careful evaluation of both the mother and fetus upon presentation to the labor and delivery suite is important due to the possibility of acute changes in status.

• Attention to the principles of normal labor and maternal–fetal physiology is imperative to avoid unnecessary interventions.

• Continuous electronic fetal monitoring has not been shown to be beneficial in any prospective, randomized controlled study. Nonetheless, its utilization is customary in many labor and delivery suites (1).

• Maternal request is sufficient justification for providing pain relief during labor.

• Routine use of episiotomies is not recommended as it has not been shown to improve outcomes. Restricted use is preferable (2,3).

BACKGROUND

Definition

• Labor is the process by which contractions of the gravid uterus expel the fetus.

• A term pregnancy delivers between 37 and 42 weeks from the last menstrual period (LMP).

• Preterm delivery is birth that occurs before 37 completed weeks of gestational age.

• Postterm pregnancy occurs after 42 weeks of gestation and requires careful monitoring secondary to increased perinatal morbidity and mortality (4).

• Termination of pregnancy before 20 weeks of gestation is defined as either spontaneous or elective abortion.

EVALUATION OF THE LABORING PATIENT

• Evaluation of the patient presenting with symptoms of labor includes

• History

• Physical examination

• Selected laboratory tests

• Fetal assessment

• A clinical impression and management plan are formulated from the information obtained.

History

History of the Present Labor

• Contractions:

• The onset, frequency, duration, and intensity of uterine contractions should be determined.

• Contractions that effect progressive cervical effacement and dilation are usually regular and intense (the patient may no longer be able to walk or talk during these contractions). They may be accompanied by a “bloody show,” the passage of blood-tinged mucus from the effacing cervix.

• Braxton-Hicks contractions are commonly experienced by many women during the last weeks of pregnancy. These are usually irregular, mild, not well organized, and do not result in cervical change.

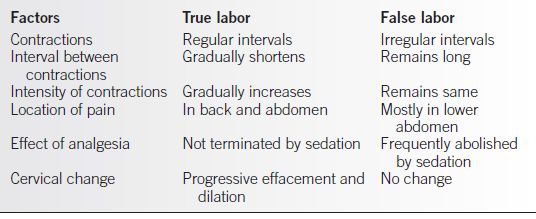

• Factors that differentiate true labor from false or prodromal labor are listed in Table 2-1.

Table 2-1 Differentiating True Labor and False Labor

• Rupture of membranes:

• The status of the fetal membranes must be determined if it is not reported as part of the initial presentation.

• The patient may present with leaking fluid alone or in conjunction with uterine contractions. The time of occurrence is important, because prolonged membrane rupture increases the risk of chorioamnionitis (5). Color of the amniotic fluid may suggest the presence of meconium or blood.

• The patient may report a large gush of fluid with continued leakage, which would lead to a high suspicion for ruptured membranes.

• The patient may report merely increased moisture on her underclothes, which leads to uncertainty about whether this moisture represents urine, vaginal secretions, cervical mucus, or amniotic fluid.

• Confirmation of rupture of membranes (ROM) may include physical examination, laboratory testing (nitrazine or fern test), ultrasonography, and/or other laboratory screening tests such as AmniSure (6).

Vaginal Bleeding

• The extent, if any, of vaginal bleeding should be ascertained.

• Spotting or blood-tinged mucus is common in normal labor.

• Heavy vaginal bleeding merits complete investigation because it may be abnormal and reflect a significant complication (see Chapter 32).

Fetal Movement

• The initial assessment of the patient reporting symptoms of labor should include questions about the level of her fetus’s movement. Most patients are aware of their fetus’s baseline level of activity.

• If the patient reports a significant or progressive decrease in fetal movement from her normal baseline, fetal well-being must be ascertained.

• Such evaluations can involve fetal monitoring with a nonstress test (NST), a contraction stress test (CST), or biophysical profile (BPP) (see Chapter 32).

• Fetal movement-counting protocols (aka “kick counts”) are commonly used in the third trimester as a screen for fetal well-being (7).

History of Current Pregnancy

• The history of the present pregnancy should be obtained by interviewing the patient in labor and by reviewing the prenatal record (8).

• The prenatal record may be from one’s own institution or from an outside source. The patient, of course, may have had no prenatal care or have no record of it.

• If a prenatal record is available, important items should be verified with the patient.

Gestational Age

• Gestational age is best determined from data in the prenatal record including ultrasound data.

• The later the patient presents for initial prenatal care, the more difficult it becomes to accurately determine the estimated gestational age (EGA).

• Patients presenting for initial prenatal care at ≥24 weeks of gestation are considered to have inherently unreliable dates.

• Important landmarks for determining gestational age include

• The 1st day of the LMP—the estimated date of confinement (EDC) is calculated as 40 weeks or 280 days from this date, based on regular 28-day cycles

• The date of last ovulation (as determined by an ovulation prediction kit or basal body temperature chart), or the date of conception (if known precisely), with the EDC calculated as 38 weeks from this date

• Early ultrasound measurement of crown–rump length at 6 to 12 weeks of gestation (accurate to within 3 days) (9)

• The average of multiple biometric measurements on fetal ultrasound between 12 and 20 weeks of gestation (accurate to within 10 days)

• Fetal heart tones, first heard with a Doppler instrument at 10 to 12 weeks of gestation or with a fetoscope at 18 to 20 weeks of gestation

• Quickening (maternally perceived fetal movement), which first occurs at approximately 18 to 20 weeks of gestation in primigravidas

• Uterine size on pelvic examination before 16 weeks of EGA, as determined by an experienced clinician

• Accurate dating requires evaluation during the first half of pregnancy.

• The patient presenting in labor with an uncertain LMP and no prenatal care may be difficult to date with accuracy.

• Uncertain gestational age presents a significant problem because of different management strategies for term, preterm, and postterm pregnancies. In these situations, the only alternative is to use ultrasonography in the labor and delivery suite, realizing that it may, at best, be accurate to within only ±3 weeks of gestation in the last trimester.

• Amniocentesis to assess fetal lung maturity can be considered to help guide delivery decisions when gestational age is uncertain.

Medical Problems Arising during Gestation

• The patient should be questioned specifically regarding any medical problems arising during the pregnancy.

• Hospitalizations should be noted, as well as any new medications prescribed.

• A history of genital herpes, bleeding, abnormal placentation, hepatitis B/C, HIV, group B streptococcus (GBS) carrier status, recurrent urinary tract infections and pyelonephritis, or any infectious diseases requiring treatment should be elicited.

• A history of glucose intolerance and treatment with diet or insulin should be noted.

• If any blood pressure elevation has been recorded during the pregnancy, the time of onset, severity, and treatment should be determined.

• Seizure history, noting frequency and medications, is pertinent for obstetric care.

• Any drug usage with illicit or prescription drugs should also be discussed.

Review of Systems

• An obstetrically oriented review of symptoms should be carried out.

• Severe headaches, scotomata, hand and facial edema, or epigastric pain may suggest preeclampsia.

• Generalized pruritus may be secondary to intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy or hepatitis.

• Dysuria, urinary frequency, or flank pain may indicate cystitis or pyelonephritis.

History of Past Pregnancies

Each past pregnancy and its duration and outcome should be reviewed.

• Particular attention should be paid to preterm deliveries, operative deliveries, prolonged or difficult labors, shoulder dystocias (up to 16.7% risk of recurrence) (10,11), malpresentation, hypertensive disorders of pregnancy (4% in the general population with a high recurrence rate) (12), placental abruption (20-fold increased risk of recurrence) (13) or placenta previa (risk increases with age, parity, and prior cesarean deliveries) up to 3% for three or more cesarean deliveries (14), and blood loss requiring transfusion.

• Other medical facilities may need to be contacted for records to verify or clarify certain points.

Medical History

• All active medical problems should be evaluated and the extent of the disease determined (i.e., epilepsy, hypertension, asthma, diabetes, heart disease, etc.).

• The stress of labor can aggravate many medical problems and jeopardize both maternal and fetal well-being and may require appropriate consultations from subspecialists.

Psychosocial and Emotional History

• Labor is a stressful physical and psychological event, and understanding the patient’s psychosocial and emotional status and history will help in planning for her care and maintaining her sense of control.

• How the patient wishes to be addressed should be determined.

• Her preparation and plans for labor and birth should be discussed.

• The patient’s labor support person(s) and their preparation should be identified.

• Questions about substance and alcohol use or abuse, intimate partner violence, and diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders should be included. This part of the history must be obtained from the patient without any family or support persons present.

• Plans for breast-feeding after delivery regardless of mode of delivery should be discussed prior to delivery.

Physical Examination

• Although active labor is not the optimal setting for a comprehensive physical examination, a focused examination with emphasis on the abdomen and pelvis can be performed between painful contractions.

• Any signs of intercurrent medical illness or abnormalities of major organ systems should be elicited and carefully noted.

• Special note should be taken of those parts of the physical examination that may generate abnormal findings because of that individual patient’s history.

General Examination

Vital Signs

• A complete set of vital signs should be taken immediately on admission including a pulse oximeter for oxygen saturation if possible.

• Blood pressure should be taken between contractions in the upright or left lateral recumbent position with the patient’s arm at the level of the heart. The appropriate size cuff should be utilized with the cuff length 1.5 times the upper arm circumference or cuff with a bladder enclosing 80% of the arm (15). Abnormal readings should be rechecked.

• An elevated body temperature, especially if associated with ruptured membranes, may indicate chorioamnionitis.

• An elevated pulse or respiratory rate in the absence of any other abnormality is commonly observed in healthy patients in active labor.

Head and Neck

• Funduscopy may be indicated to rule out vascular abnormalities, hemorrhages, or exudates that may suggest such diseases as diabetes or hypertension.

• Pale conjunctivae (or nail beds) may suggest anemia.

• Facial, most notably periorbital, edema can be found—in preeclampsia.

• The thyroid gland should be palpated to rule out goiter or other masses and to determine if anesthesia should be involved for any concerns related to airway management.

• Distended neck veins suggest congestive heart failure, which, although rare, is a serious complication of labor and should be recognized early so that proper therapy may be initiated.

Chest

• Examination of the chest may reveal the presence of a pneumonic process or significant cardiac murmurs (other than the physiologic systolic ejection murmur common in pregnancy) and provides a baseline in case complications such as pulmonary edema develop.

• Auscultation of the lungs for rales, crackles, and wheezes is especially important in patients with asthma or hypertension or at risk for pulmonary edema.

Abdomen

• An attempt should be made to palpate major abdominal viscera for pain or masses, although this is difficult with a term-sized uterus.

• Epigastric tenderness may suggest preeclampsia or HELLP (hemolysis, elevated liver enzyme levels, and a low platelet count) syndrome.

Extremities

• Examination of extremities should include an assessment of peripheral edema.

• Although mild ankle edema commonly is found near term in normal pregnancies, severe lower extremity or hand edema may suggest preeclampsia. Unilateral edema also may suggest underlying VTE (venous thromboembolism).

• A brief neurologic examination should be performed because the presence of deeptendon hyperreflexia and clonus may suggest a lowered threshold for seizure activity.

The Gravid Uterus

• A general examination includes assessment for the size of the uterus, presence of tenderness, globular masses (i.e., fibroids), estimated fetal weight (EFW), and fetal presentation and lie.

• Presence of uterine tenderness may by indicative of chorioamnionitis, uterine rupture, or placenta abruption, all of which require prompt attention.

Uterine Size

• After 20 weeks, the size of the uterus is anticipated to correlate with the number of centimeters from the pubis to the top of the fundus in a singleton pregnancy.

• Correlation of these findings lessens as the pregnancy approaches term due to variation in fetal size and pelvic engagement.

• Significant lack of correlation raises concern for the presence of a fetal growth or amniotic fluid disorder or multiple gestation. Size date discrepancy can also be due to the influence of pelvic engagement.

• Ultrasonography is indicated to resolve concerns of size date discrepancy.

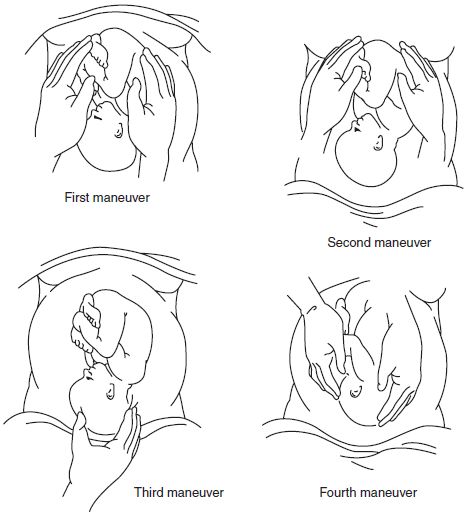

Leopold Maneuvers

• Leopold maneuvers (Fig. 2-1) are a technique used to palpate the gravid uterus to determine fetal presentation and fetal lie. It can also be used to estimate fetal weight (mentally adjusting for maternal habitus, amniotic fluid, and proportion of fetus engaged in the pelvis). Ultrasound can be used for primary assessment of these clinical factors or as confirmation of the Leopold maneuvers.

• The first maneuver determines which fetal pole occupies the uterine fundus (e.g., the breech with a vertex presentation). The breech moves with the fetal body. The vertex is rounder and harder and feels more globular than the breech and can be maneuvered separately from the fetal body.

• With the second maneuver, the lateral aspects of the uterus are palpated to determine on which side the fetal back or fetal extremities, or “small parts,” are located. The back is firm and smooth.

• The third maneuver is performed with the examiner facing caudally, and the presenting part is made to move from side to side. If this is not done easily, engagement of the presenting part probably has occurred.

• The fourth maneuver reveals the presentation. With the fetus presenting by vertex, the cephalic prominence may be palpable on the side of the fetal small parts, confirming flexion of the fetal head (occiput presentation). Extension of the head (face presentation) is suspected when the cephalic prominence is on the side of the fetus opposite the small parts.

Figure 2-1. Leopold maneuvers to diagnose fetal presentation and position of the fetus. (Gibbs RS, Karlan BY, Haney AF, et al. Danforth’s obstetrics and gynecology. 10th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2008:22–41, Figure 6.)

Fetal Lie

• The lie of the fetus is a description of the relationship of the long axis of the fetus to the long axis of the mother. The lie is longitudinal with a vertex or breech presentation or otherwise transverse or oblique, as with a shoulder presentation.

Presentation

• Designates the part of the fetus lowest in the pelvis.

• Cephalic denotes the fetal head presenting to the pelvis.

• Vertex, presentation of the occipital fontanelle due to flexion of the fetal head to the fetal chest is the most common.

• Deflexion of the fetal head leads to sinciput (presentation of anterior fontanelle), brow (bregma), or face presentations.

• Breech presentations are classified by presentation of the buttocks with or without the feet.

• Frank breech presentation: Both hips are flexed with the knees extended.

• Complete breech: Both hips are flexed with one or both knees flexed.

• Incomplete breech: One or both hips deflexed with one or both feet or knees below the buttocks.

• Footling breech is an incomplete breech with one or both feet located below the buttocks.

• Shoulder presentation is found with transverse lie.

• Compound presentation is presentation of an extremity with the presenting part.

Estimated Fetal Weight

• EFW can be assessed with palpation of the gravid uterus and mentally adjusting for maternal habitus, amniotic fluid, and proportion of fetus engaged in the pelvis.

• Discrepancy between the gestational age and anticipated fundal height suggests growth or fluid volume abnormality or multiple gestation. Ultrasound examination will be necessary for resolution.

• EFW calculated by ultrasound has a margin of error of up to 20% (9,16).

Fetal Heart Tones

• Documentation of the fetal heart tones must be performed on admission.

• Continuous electronic fetal heart rate monitoring (CEFM) is performed as an initial evaluation at many institutions. The baseline heart rate, variability, accelerations, and decelerations are carefully assessed, and categorization of the tracing is performed accordingly (1,17,18) (see Chapter 22).

• If a reassuring tracing is obtained, the patient may continue to be managed with CEFM or may be a candidate for intermittent fetal heart rate monitoring by auscultation.

Pelvic Examination

• Inspection and palpation of the perineum and the pelvis are critically important in evaluating the laboring patient.

• Information needed includes

• Presence or absence of perineal, vaginal, and cervical abnormalities (including herpes or human papillomavirus infections)

• Adequacy of the bony pelvis

• Integrity of the fetal membranes

• Degree of cervical dilation and effacement

• Station of the presenting part

• The presence of third-trimester vaginal bleeding or preterm premature rupture of the membranes will preclude digital examination of the cervix until further evaluation is performed, which may include bedside ultrasound.

Inspection

• The perineum should be inspected for herpetic or syphilitic lesions, large vulvar varicosities, large condylomas, or other altered vulvar anatomy, that is, female genital mutilation.

• If there is any question of active genital herpes, a speculum examination of the vagina or cervix is necessary.

• Diagnosis of ruptured membranes may sometimes be visually confirmed by inspection, but it is often necessary to perform a sterile speculum examination to determine the status of the fetal membranes.

• Using sterile technique, a sterile speculum is inserted into the vagina, and a light source is positioned so the cervix and posterior vagina can be visualized.

• Gross pooling of amniotic fluid in the posterior fornix is consistent with the diagnosis of ROM. It is important to note the color and consistency of the fluid, the presence of purulence, blood, or meconium.

• Direct transcervical visualization of fetal scalp, feet, umbilical cord, or other fetal parts confirms ruptured membranes definitively.

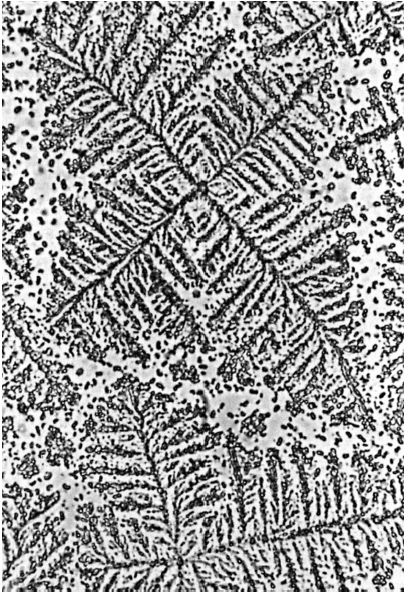

• If uncertain about ROM, any fluid pooled in the posterior vaginal fornix is sampled with a sterile cotton swab, smeared on a glass slide, and viewed with the aid of a microscope. Other laboratory methods for the evaluation of ROM are available, that is, AmniSure (6).

Ferning of the air-dried fluid under the microscope suggests amniotic fluid (Fig. 2-2).

Ferning of the air-dried fluid under the microscope suggests amniotic fluid (Fig. 2-2).

Ultrasound may be used to evaluate amniotic fluid volume if the status of the membranes is still uncertain after physical and laboratory testing.

Ultrasound may be used to evaluate amniotic fluid volume if the status of the membranes is still uncertain after physical and laboratory testing.

• If bloody amniotic fluid is noted (port-wine fluid), further investigation to rule out abruptio placentae should be undertaken.

• The absence or presence of meconium (fetal stool) in the amniotic fluid should be noted.

The incidence of meconium-stained amniotic fluid increases with advancing gestational age.

The incidence of meconium-stained amniotic fluid increases with advancing gestational age.

• Cultures are obtained when preterm labor or chorioamnionitis is suspected.

• With preterm ROM at 32 to 34 weeks, a sample of amniotic fluid from the vaginal pool can be obtained to evaluate fetal lung maturity to assist with management decisions regarding expectant management (19).

Figure 2-2. “Ferning” in smear from the vagina suggests that amniotic fluid is present in the vagina.

Palpation of the Cervix

• Palpation of the cervix should be done when the patient is between contractions to ensure accuracy and to minimize the patient’s discomfort.

• Dilation of the cervix describes the degree of opening of the internal cervical os. The cervix can be described as undilated or closed (0 cm), fully dilated (10 cm), or any point between these two extremes (0 to 10 cm).

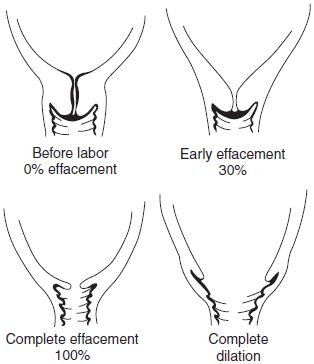

• Effacement of the cervix describes the process of thinning that the cervix undergoes before or during labor (Fig. 2-3).

• The thick prelabor cervix is approximately 3 cm long and is said to be uneffaced or to have 0% effacement. With complete or 100% effacement, the cervix is paper thin.

• As a general rule, primiparous women begin to efface the cervix before dilation begins, whereas multiparous women begin to dilate before significant effacement has been reached.

Figure 2-3. Cervical effacement and dilation in the primigravida. (LifeART image copyright (c) 2013 Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. All rights reserved.)

Palpation of the Fetal Presenting Part

• Identification of fetal presentation should be confirmed by digitally palpating the fetal presenting part. The novice often assumes it to be a vertex, but identification must be positively made on every occasion.

• Vertex presentation can be confirmed by palpating the suture lines of the fetal skull. If the suture lines cannot be identified with certainty, other presentations must be considered.

• Palpation of the fetal buttocks, feet, face, or arms is confirmatory.

• Inability to positively identify the presenting part is an indication for expeditious ultrasound examination.

• Station refers to the relationship between the fetal presenting part and pelvic landmarks.

• When the presenting part is at zero station, it is at the level of the ischial spines, which are the landmarks for the midpelvis. This is important in the vertex presentation because it implies that the largest dimension of the fetal head, the biparietal diameter, has passed through the smallest dimension of the pelvis, the pelvic inlet.

• In 1988, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists introduced a classification dividing the pelvis into 5-cm segments above and below the ischial spines:

If the presenting part is 1 cm above the spines, it is described as −1 station.

If the presenting part is 1 cm above the spines, it is described as −1 station.

If it is 2 cm below the spines, the station is +2.

If it is 2 cm below the spines, the station is +2.

At −5 station, the presenting part is described as floating.

At −5 station, the presenting part is described as floating.

At +5 station, the presenting part is on the perineum, and it may distend the vulva with a contraction and be visible to an observer.

At +5 station, the presenting part is on the perineum, and it may distend the vulva with a contraction and be visible to an observer.

In practice, this system has not been widely adopted, and many physicians still describe station on the basis of dividing the maternal pelvis below the spines into thirds. An approximation would be, for example, +4 cm = +2/3.

In practice, this system has not been widely adopted, and many physicians still describe station on the basis of dividing the maternal pelvis below the spines into thirds. An approximation would be, for example, +4 cm = +2/3.

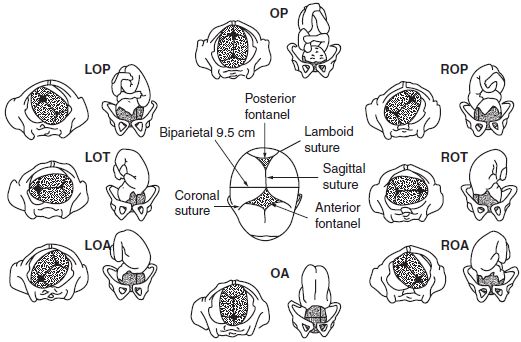

• Position of the presenting part is described as the relationship between a certain landmark on the fetal presenting part and the maternal pelvis (Fig. 2-4), as follows:

Anterior, closest to the symphysis pubis

Anterior, closest to the symphysis pubis

Posterior, closest to the coccyx

Posterior, closest to the coccyx

Transverse, closest to the left or right vaginal sidewall

Transverse, closest to the left or right vaginal sidewall

The index landmark in a vertex presentation is the occiput, which is identified by palpating the lambdoid sutures forming a Y with the sagittal suture; it is the sacrum in a breech presentation and the mentum (or chin) in a face presentation.

The index landmark in a vertex presentation is the occiput, which is identified by palpating the lambdoid sutures forming a Y with the sagittal suture; it is the sacrum in a breech presentation and the mentum (or chin) in a face presentation.

The designations of anterior, posterior, left, and right refer to the maternal pelvis. Therefore, right occiput transverse implies that the occiput is directed toward the right side of the maternal pelvis.

The designations of anterior, posterior, left, and right refer to the maternal pelvis. Therefore, right occiput transverse implies that the occiput is directed toward the right side of the maternal pelvis.

• Breech and face presentations are described in a similar fashion (e.g., right sacrum transverse, right mentum transverse).

Figure 2-4. Vaginal palpation of the large and small fontanelles and the frontal, sagittal, and lambdoidal sutures determines the position of the vertex. Various vertex presentations. LOP, left occiput posterior; LOT, left occiput transverse; LOA, left occiput anterior; ROP, right occiput posterior; ROT, right occiput transverse; ROA, right occiput anterior. (Beckmann CRB, Frank W, et al. Obstetrics and gynecology. 5th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2006.)

Evaluation of Pelvic Adequacy

• The shape of the maternal pelvis may be visualized as a cylinder with a gentle anterior curve toward the outlet. The curve forms because the posterior border of the pelvis (the sacrum and the coccyx) is longer than the anterior border (the symphysis pubis). The lateral borders (the innominate bones) are more or less parallel in the normal female pelvis.

• Dystocia may be encountered when abnormalities of the pelvis are present. Pelvic adequacy can be judged clinically by measuring pelvic diameters at certain levels.

• Even when conducted by the most experienced clinicians, clinical pelvic measurements are merely estimations.

• Unless the maternal pelvis is grossly contracted, adequacy is proven only by a trial of labor.

• Despite this, the pelvis must be evaluated at admission for an estimate of adequacy or documentation of abnormalities.

• The maternal pelvis is one of three factors that determine the success of labor. These factors have been referred to as the three P’s: Pelvis, Power, and the Passenger. A macrosomic fetus or inadequate uterine contractions, even with an adequate pelvis, may preclude vaginal delivery.

Inlet

• The inlet of the true pelvis is limited by the symphysis pubis anteriorly, the sacral promontory posteriorly, and the iliopectineal line laterally.

• The anteroposterior (AP) diameter of the inlet may be estimated by determining the diagonal conjugate measurement. The diameter (the distance from the sacral promontory to the inner inferior surface of the symphysis pubis) is measured clinically by attempting to touch the sacral promontory with the vaginal examining finger while simultaneously noting where the inferior border of the symphysis touches the examining finger. A measurement greater than 12 cm suggests adequacy.

Midpelvis

• The midpelvis is bordered anteriorly by the symphysis pubis, posteriorly by the sacrum, and laterally by the ischial spines. A gently curved concave sacrum increases the adequacy of the midpelvis.

• The interspinous diameter is estimated by palpating the ischial spines. An estimated distance less than 9 cm suggests midpelvis contraction. Experience is required to estimate this diameter with accuracy.

Outlet

• The outlet is limited anteriorly by the arch of the symphysis pubis, posteriorly by the tip of the coccyx, and laterally by the ischial tuberosities.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree