Materials and Methods

Subjects

We conducted a prospective cohort study of children who were born late preterm (32-36 weeks of gestation) or at term (≥37 weeks of gestation) after threatened preterm labor between September 2011 and May 2013 at a tertiary University Center. Congenital malformations, chromosomopathy, infections, multiple gestations, postnatal diagnosis of children with a severe disease, and delivery not in our medical center were excluded. This cohort was compared with a group of children who were born from singleton pregnancies at term (≥37 weeks of gestation) without threatened preterm labor, randomly sampled from our general obstetric population during the same time period. The local ethics committee approved the study protocol, and parents provided written informed consent.

Threatened preterm labor was defined as the presence of regular and painful uterine contractions that registered by cardiotocography and ultrasound cervical length <25 mm in the presence of intact membranes at gestational age of 24+0 to 36+6 weeks. Pregnancies were dated according to first-trimester crown-rump length. Tocolysis with atosiban (Tractocile; Ferring Pharmaceuticals, Madrid, Spain) and intramuscular betamethasone (2×12 mg/24 hr) was performed for some cases according to manufacturer recommendations and international clinical standards.

Maternal sociodemographic characteristics were recorded in the hospital database at study inclusion. Information regarding pregnancy follow up and standard perinatal outcomes was collected prospectively. Infants with a birthweight of <10th percentile, according to local standards, were considered to be small-for-gestational age. Umbilical, uterine, and middle cerebral artery Doppler scans were carried out in small-for-gestational age fetuses to diagnose intrauterine growth restriction. Metabolic acidosis was defined as the presence of an umbilical artery pH <7.10 and base excess > –12 mEq/L.

Neurodevelopmental assessment

Neurodevelopment was assessed at a corrected age of 24-29 months with the use of the Merrill-Palmer-Revised Scales of Development (M-P-R), which assesses cognitive (verbal and nonverbal reasoning memory), language/communication (receptive and expressive language, evaluated by examiner and parent), and motor (fine motor and gross motor) abilities. Especially useful in assessing children who were born preterm, the M-P-R is a standardized measure of development that is used with children aged 1 month to 78 months that permits an early identification of developmental delays and learning difficulties. This test is ideal for the screening of infants and children with possible developmental delays or disabilities and for revaluations of individuals who previously were identified as developmentally delayed. It provides a global assessment with criterion-specific scores. Two trained psychologists who were blind to group and perinatal outcomes conducted the assessment. Children were assessed in the afternoon in a quiet room in the presence of at least 1 parent. M-P-R subtest scores <1 standard deviation were considered as mild neurodevelopmental delay. The main reason of missing during this period was the impossibility of contacting the patients because of address and telephone changes.

Statistical analysis

Normal distributions were assessed with the use of the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Chi-square tests and analysis of variance were used to analyze categoric and continuous variables, respectively. Significant effects were followed by Bonferroni correction. Effect sizes were calculated with the use of odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs). Data are presented as mean±standard deviation (SD), median (range), or number of subjects (%). Two-sided probability values of <.05 were considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SPSS software (version 20; SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL).

Results

Of the 108 children who met the inclusion criteria, we contacted 98 parents and received consent from 87 parents. Forty-five women were admitted to the hospital for threatened preterm labor during pregnancy; 22 women gave birth to infants late preterm, and 23 women gave birth to infants at term. The other 42 women gave birth to infants at term without threatened preterm labor.

Clinical characteristics and perinatal outcomes are shown in Table 1 . Women who gave birth late preterm or at term after threatened preterm labor were significantly more likely to have had a previous preterm birth compared with control women ( P =.02). As expected, late preterm infants had significantly lower birthweights and younger gestational ages at delivery and were more likely to be admitted to the neonatal unit ( P <.001). We found no differences in maternal educational level among the groups. The administration of corticosteroids for fetal lung maturation was performed for all infants who were born at term after threatened preterm labor, but it was performed for only 54.5% of infants who were born late preterm because labor could not be arrested or hospital admission for threatened preterm labor took place after 34 weeks of gestation.

| Variable | Born late preterm (n=22) | Born at term after threatened preterm labor (n=23) | Born at term (n=42) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal age, y a | 31±5.3 | 30.6±5.0 | 32.1±5.5 | .49 |

| Maternal body mass index, kg/m 2 a | 24.2±3.5 | 21.9±3.2 | 23.6±3.4 | .10 |

| White ethnicity, n (%) | 18 (82) | 22 (96) | 37 (88) | .35 |

| Maternal educational level, n (%) | .56 | |||

| None | 1 (5) | 1 (4) | 0 | |

| Primary | 4 (20) | 7 (30) | 6 (14) | |

| Secondary | 10 (45) | 8 (35) | 20 (48) | |

| University | 7 (30) | 7 (30) | 16 (38) | |

| Nulliparous, n (%) | 11 (50) | 14 (65) | 22 (53) | .52 |

| Previous preterm birth, n (%) | 5 (24) | 3 (13) | 0 | .02 |

| Preeclampsia, n (%) | 0 | 0 | 2 (5) | .30 |

| Cesarean delivery, n (%) | 1 (5) | 6 (26) | 6 (14) | .13 |

| Operative vaginal delivery, n (%) | 2 (9) | 3 (13) | 9 (21) | .40 |

| Spinal anesthesia, n (%) | 17 (77) | 21 (91) | 38 (91) | .26 |

| Gestational age at delivery, d a | 246.6±8.5 | 276.8±7.7 | 278.2±8.4 | <.001 |

| Birthweight, g a | 2463±457 | 3131±402 | 3336±400 | <.001 |

| Male, n (%) | 10 (46) | 13 (57) | 18 (43) | .56 |

| Small for gestational age, n (%) | 2 (9) | 5 (22) | 3 (7) | .21 |

| Antenatal corticosteroid treatment, n (%) | 12 (55) | 23 (100) | 0 | <.001 |

| Metabolic acidosis, n (%) | 0 | 1 (4) | 1 (2) | .62 |

| Neonatal unit admission, n (%) | 11 (50) | 1 (5) | 2 (5) | <.001 |

| Breastfeeding, n (%) | 21 (95) | 22 (96) | 36 (86) | .28 |

| Age at assessment, mo a | 26.4±1.2 | 26.0±2.2 | 26.1±1.3 | .61 |

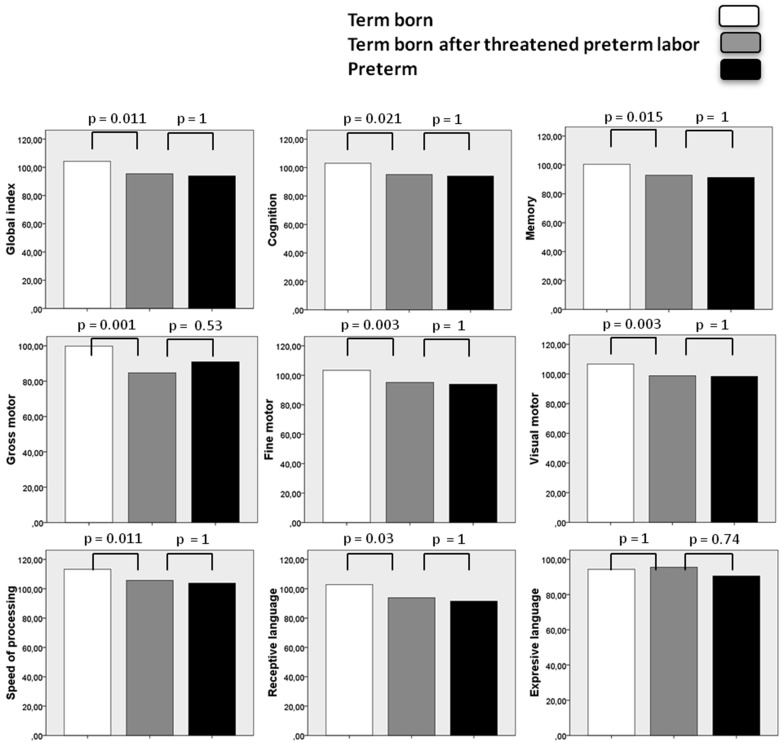

Average scores on M-P-R subtests are shown in Table 2 . There were significant effects of groups on all subtest scores, except for expressive language score. The results of Bonferroni post-hoc tests are shown in the Figure . Children who were born at term after threatened preterm labor scored significantly lower than children who were born at term in global cognitive index, cognition, fine and gross motor, memory, receptive language, speed of processing, and visual motor coordination. No significant differences were observed between children who were born at term after threatened preterm labor and children who were born late preterm.

| Variable | Born late preterm (n=22), mean±standard deviation | Born at term after threatened preterm labor (n=23), mean±standard deviation | Born at term (n=42), mean±standard deviation | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age at evaluation, mo | 26.4±1.25 | 25.9±2.21 | 26.1±1.34 | .610 |

| Global cognitive index | 93.9±12.3 | 95.4±12.2 | 104±13.4 | .001 |

| Cognition | 94.0±11.2 | 95.1±11.5 | 103±10.7 | .003 |

| Fine motor | 93.9±8.97 | 95.2±10.1 | 103±8.92 | <.001 |

| Gross motor | 91.0±15.4 | 84.7±18.0 | 99.8±12.8 | .001 |

| Memory | 91.4±9.73 | 92.9±11.6 | 100±9.29 | .001 |

| Receptive language | 91.5±14.8 | 93.9±13.7 | 103±11.7 | .002 |

| Expressive language | 90.6±14.6 | 95.6±14.7 | 94.4±13.8 | .470 |

| Speed of processing | 104±11.9 | 106±11.5 | 113±6.85 | <.001 |

| Visual motor | 98.4±8.53 | 98.8±8.77 | 107±9.21 | <.001 |

Following standard methodology, the presence of mild neurodevelopmental delay was adjusted for gestational age at birth, birthweight, gender, cesarean delivery, and maternal education (secondary education or higher) by logistic regression analysis. ( Table 3 ) Children who were born at term after threatened preterm labor had a significantly increased risk of mild neurodevelopmental delay compared with children who were born at term for all cognitive domains, except for cognition ( P =.071) and expressive language ( P =.91).

| Variable | Born at term after threatened preterm labor (n=23), % | Born at term (n=42), % | Odds ratio | 95% Confidence interval | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global cognitive index | 47.8 | 14.6 | 2.06 | 1.09–3.88 | .004 |

| Cognition | 43.5 | 22.0 | 1.60 | 0.86–2.97 | .071 |

| Fine motor | 60.9 | 26.8 | 2.10 | 1.16–3.81 | .007 |

| Gross motor | 56.6 | 22.5 | 1.98 | 1.09–3.60 | .006 |

| Memory | 56.5 | 26.8 | 1.84 | 1.02–3.29 | .019 |

| Receptive language | 43.5 | 14.6 | 1.92 | 1.02–3.66 | .011 |

| Expressive language | 22.7 | 21.4 | 1.19 | 0.60–2.23 | .910 |

| Speed of processing | 43.5 | 17.1 | 1.93 | 1.03–3.60 | .022 |

| Visual motor | 52.2 | 12.2 | 2.65 | 1.36–5.27 | .001 |

As increased risk of cognitive deficits was observed for both children who were born late preterm and children who were born at term after threatened preterm labor, we analyzed M-P-R subtest scores according to treatment with antenatal corticosteroids to identify any potential bias. There were no statistically significant differences between groups in any cognitive domains (data not shown; probability values ranged from .46–.90).

Finally, the estimated power of this study (with previously reported differences among groups in global cognitive index taken into account) was 0.96 as calculated by a 1-way analysis of variance pairwise 2-sided equality test.

Results

Of the 108 children who met the inclusion criteria, we contacted 98 parents and received consent from 87 parents. Forty-five women were admitted to the hospital for threatened preterm labor during pregnancy; 22 women gave birth to infants late preterm, and 23 women gave birth to infants at term. The other 42 women gave birth to infants at term without threatened preterm labor.

Clinical characteristics and perinatal outcomes are shown in Table 1 . Women who gave birth late preterm or at term after threatened preterm labor were significantly more likely to have had a previous preterm birth compared with control women ( P =.02). As expected, late preterm infants had significantly lower birthweights and younger gestational ages at delivery and were more likely to be admitted to the neonatal unit ( P <.001). We found no differences in maternal educational level among the groups. The administration of corticosteroids for fetal lung maturation was performed for all infants who were born at term after threatened preterm labor, but it was performed for only 54.5% of infants who were born late preterm because labor could not be arrested or hospital admission for threatened preterm labor took place after 34 weeks of gestation.