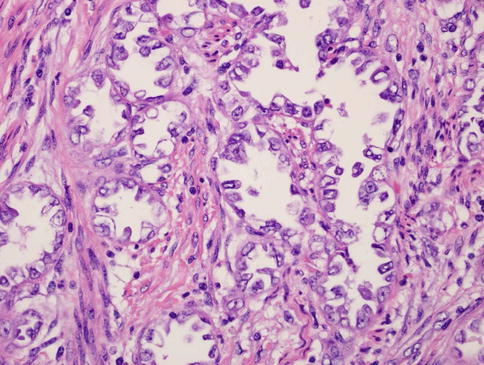

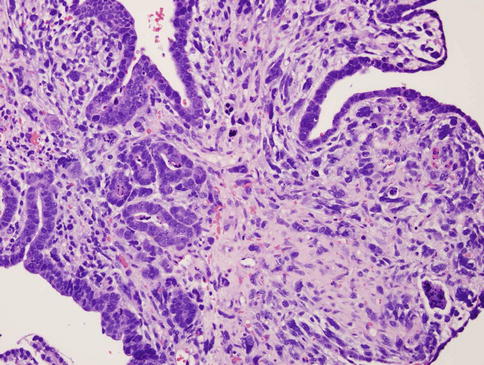

Fig. 23.1

Uterine papillary serous carcinoma. Note the fibrovascular core lined by stratified, pleomorphic cells, forming secondary papillae and cellular buds

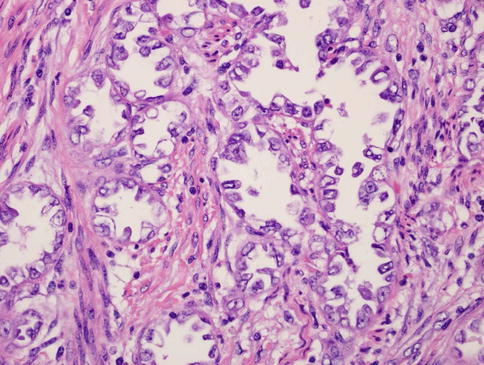

Clear-cell cancers are more varied, often characterized by tubulocystic, solid, and papillary patterns. The name clear cell is given due to the increased percentage of glycogen within the cell. Because of the varied histology of clear-cell carcinoma, diagnosis requires at least 25 % of the tumor to illustrate a clear-cell component [5]. Clear-cell endometrial adenocarcinomas are histologically similar to those arising from the ovary, vagina, and the cervix [4]. As in UPSC, clear-cell carcinomas are high grade and tend to be deeply invasive (Fig. 23.2).

Fig. 23.2

Clear-cell uterine carcinoma. Note the clear, glassy cytoplasm, enlarged angulated nuclei with enlarged irregular nucleoli, and hobnail appearance

If the serous component of a tumor is greater than 10 % but less than 90 %, the tumor is considered mixed serous histology. Typically, the other fraction of the tumor is endometrioid histology. Once thought to have similar survival, a multi-institutional review compared patients with UPSC to those with mixed UPSC and found that the pure UPSC group had an almost threefold risk of recurrence and death than the mixed-cell histology [5]. This holds true for pure clear-cell versus mixed clear-cell histology. These patients historically do relatively the same with regard to survival [6].

While type I tumors are associated with mutations in PTEN, K-ras, and microsatellite instability [7], type II are most commonly found to have p53 mutations and/or Her-2/neu overexpression [8, 9]. P53 is a tumor suppressor gene that regulates transcription and initiates apoptosis in the event of DNA damage. When a mutation or defect in p53 occurs, proliferation of tumor cells occurs. It is thought that approximately 50 % of cancers arise from this defect. It is still currently scrutinized whether BRCA1/2 mutation carriers have an increased risk for UPSC; however a recent study by Pennington et al. did demonstrate a higher than expected BRCA1 mutation rate at 2 % [10]. Given this finding, it has been suggested that women with a diagnosis of UPSC be offered genetic counseling and testing. Additional data suggests that epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) expression correlates with a poorer prognosis in both type I and II endometrial carcinoma, reducing survival in UPSC and clear-cell carcinomas from 86 % to 27 % [11]. While Her-2/neu is thought to play a role in UPSC, Herceptin use has not been studied extensively in recurrent or metastatic disease, and successful treatments have only been reported in case reports [12]. Current studies are underway, particularly a phase II study of carboplatin/paclitaxel with or without trastuzumab for advanced or recurrent UPSC patients with 3+ IHC for Her2/neu. Other molecular targets include PPP2R1A, FBXW7, and PIK3CA. Mutations in the regulatory unit of PPP2R1A’s serine-threonine protein phosphatase 2 are reported in as high as 32 % of UPSC [10]. This enzyme is responsible for control of cell growth and division and is located downstream of Her2/neu, which may prove a potential target for treatment of UPSC. FBXW7 is an F-box protein important in targeting tumor-promoting proteins, including cyclin E. Cyclin E upregulates the cell cycle, particularly in the transition from G1 to S phase, in a dose-dependent manner that increases oncogenic potential [13]. A genome-wide analysis of UPSC by Kuhn et al. demonstrated that PIK3CA was mutated and/or amplified in 48 % of the sequenced patients, supporting the PIK3CA/AKT/mTOR pathway is one from which USC arises. Therefore, findings to support this notion will likely lead to adjuvant treatment with mTOR inhibitors such as rapamycin.

Surgical Management

For the majority of endometrial carcinoma patients, the first-line treatment is comprehensive surgical staging. This includes total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, and pelvic and para-aortic lymph node dissection per the International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) 2009 guidelines. Although it is common practice to collect peritoneal cytologic washings, this was not included in the 2009 FIGO recommendations. The role of lymphadenectomy is still under investigation for type I endometrioid adenocarcinoma, though recent studies support the omission of routine lymphadenectomy for superficial grade 1–2 endometrioid carcinoma in light of associated complications and lack of survival benefit [14]. In contrast, regarding grade 3 and type II carcinomas, combined pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy has been shown to improve survival [15]. The therapeutic value of removing normal-appearing, normal-sized lymph nodes has been disputed, except to provide the most accurate staging to optimize postoperative treatment modality. Fader et al. also recently performed a multicenter study demonstrating that for early-stage endometrial cancer, regardless of histology, there was no significant difference in overall survival if patients were staged with a minimally invasive approach versus open laparotomy [16].

Though studies are still ongoing, initial data suggest that use of sentinel lymph node mapping may reduce morbidity associated with full lymphadenectomy (lymphedema, increased operative time), while detecting lymph node involvement at the same rate of fully staged carcinomas [17]. Further investigation over time will yet determine optimal placement and type of dye used and the extent of any long-term complications and outcomes.

For early stage I and II type II cancers, lymphadenectomy is thought to help tailor postoperative adjuvant therapy. However, when the histology indicates a high-grade tumor, these women are likely to receive adjuvant treatment regardless of lymph node status. Additionally, as ASTEC did not guide management of type II carcinomas and given the results of SEPAL, it is still recommended that comprehensive staging with PPLND is performed. Until the results of GOG 249 (Radiation vs Brachytherapy for Endometrial Carcinoma: A Phase III Trial of Pelvic Radiation Therapy Versus Vaginal Cuff Brachytherapy Followed By Paclitaxel/Carboplatin Chemotherapy in Patients With High Risk, Early Stage Endometrial Carcinoma) are available, these are still standard, and additional procedures such as abdominopelvic washings, omentectomy, and peritoneal biopsies are still incorporated at the surgeon’s discretion due to lack of convincing evidence in favor of or against it.

Adjuvant Therapy

There is no standard adjuvant radiation therapy for early-stage endometrial carcinoma that has been set for comprehensively staged patients. However, it has been noted that with observation alone, recurrence risk in women with early UPSC and no myometrial invasion was 0–30 %. Recurrence rates in this population increased dramatically with myometrial invasion, from 29 % to 80 % [18]. Whole-abdominal radiation with and without pelvic boost has been studied, specifically in GOG 94 (a phase II study of whole-abdominal radiotherapy in patients with papillary serous carcinoma and clear cell carcinoma of the endometrium or with maximally debulked advanced endometrial carcinoma). Of 19 patients, 7 recurred. 71 % of the recurrences were within the irradiated field. A Cochrane review by Kong et al. also concluded there was no demonstrable difference in survival with whole pelvic radiation for stage I high-risk endometrial carcinoma [19]. In early-stage patients with comprehensive staging performed, adjuvant chemotherapy is also of no proven benefit. However, recurrences have been reported in disease solely confined to a polyp that did not receive adjuvant chemoradiation [20]. Therefore, in the early-staged population, treatment decisions should still be tailored to the individual, discussing the risks of recurrence versus those associated with chemoradiation, so that the physician and patient are making the most informed and responsible decision. The standard of care for patients with any evidence of remaining disease in the uterus at the time of hysterectomy should be offered adjuvant chemotherapy [2].

Standard first-line treatment for UPSC is chemotherapy with carboplatin and paclitaxel with or without vaginal brachytherapy based on GOG 209. This non-inferiority trial demonstrated that the doublet of carboplatin and paclitaxel was just as efficacious but less toxic than the triplet of doxorubicin, cisplatin, and paclitaxel. “Sandwich therapy” has also demonstrated survival rates of 75 % in early-stage disease in a phase II trial by Fields et al. [21]. In this therapy model, patients receive three cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel with whole pelvic radiation subsequently given and then receive an additional three cycles of carboplatin and paclitaxel. Additionally, Kiess et al. demonstrated that the use of six cycles of IV carboplatin and paclitaxel with only vaginal brachytherapy still elicited 85 % 5-year progression-free survival and 90 % overall [22]. A 2009 Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) consensus statement supported chemotherapy with or without radiation for early UPSC with any residual disease in the uterus at the time of hysterectomy. The recurrence risk for IA UPSC is 8.7 % for those receiving chemotherapy, while radiation-only patients have a recurrence as high as 25 %. For Stage IB and IC disease, a similar threefold increase in recurrence risk is seen with radiation or observation alone is seen [2].

Uterine Carcinosarcoma

Uterine carcinosarcoma, formerly known as malignant mixed Mullerian tumor (MMMT) is a rare neoplasm accounting for only 1–2 % of cancers of the uterus. The dedifferentiated tumors arise from the endometrium and are also considered to arise from uterine epithelial carcinoma, rather than from a true sarcoma [23, 24]. Due to the rarity of the disease, large, prospective studies have not been performed. The most common presenting complaints are a triad of vaginal bleeding, lower abdominal pain, and a rapidly growing uterus [25, 26]. The median age at diagnosis is approximately 62–67 years, with blacks affected at twice the rate of non-Hispanic whites [27]. On presentation, 60 % of patients will have extrauterine spread [28].

Evaluation both pre- and postoperatively with CA-125 has proven beneficial to identify more advanced and aggressive disease status, correlated with metastases and tumor volume. It is highly correlated with disease stage, serous component, and myometrial invasion of more than 50 % with a “positive cutoff value” of more than or equal to 30 U/mL [29] (Figs. 23.3 and 23.4).

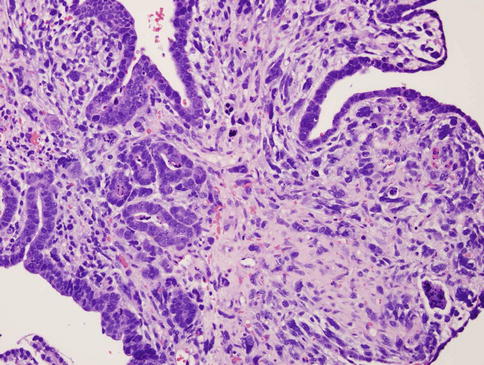

Fig. 23.3

Uterine carcinosarcoma. Heterologous MMMT with rhabdoid features. Heterologous tumors typically have mesenchymal elements such as bone, fat, skeletal muscle, or cartilage within them. Note the large, anaplastic, racquet-shaped cells with abundant cytoplasm (arrows)

Fig. 23.4

Uterine carcinosarcoma. Homologous MMMT. Note the glandular epithelial component and the stromal sarcomatous component throughout

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree