Blood and Lymph

The uterine blood supply (Fig. 3.1) is from the uterine arteries, which cross over the ureters lateral to the cervix and pass inferiorly and superiorly supplying the myometrium and endometrium. At the cornu there is an arterial anastomosis with the ovarian blood supply. Inferiorly, there is an anastomosis with the vessels of the upper vagina. Lymph drainage of the uterus (Fig. 3.1) is mostly via the internal and external iliac nodes.

The Endometrium

The endometrium is supplied by the spiral and basal arterioles. The former are important in menstruation and in nourishment of the growing fetus. The endometrium is responsive to oestrogen and progesterone. In the first 14 days of the menstrual cycle, it proliferates: the glands elongate and it thickens, largely under the influence of oestrogens (proliferative phase). After ovulation, under the influence of progesterone, the glands swell and the blood supply increases (luteal or secretory phase; see Fig. 2.3). Towards the end of this phase, progesterone levels drop and the secretory endometrium disintegrates as its blood supply can no longer support it: menstruation occurs. Poor hormonal control commonly causes erratic bleeding patterns.

Fibroids

Definition and Epidemiology

Also known as leiomyomata, these are benign tumours of the myometrium. They occur in at least 25% of women and are more common near the menopause, in Afro-Caribbean women and those with a family history. They are less common in parous women and those who have taken the combined oral contraceptive or injectable progestogens.

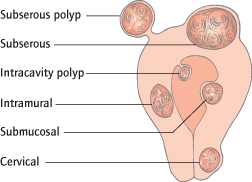

Pathology and Sites of Fibroids

The sizes vary from a few millimetres to massive tumours filling the abdomen. The fibroid may be intramural, subserosal or submucosal (Fig. 3.2). Submucosal fibroids occasionally form intracavity polyps. Smooth muscle and fibrous elements are present, and in transverse section the fibroid has a ‘whorled’ appearance.

Aetiology

Fibroid growth is oestrogen and probably progesterone dependent. During pregnancy, fibroids are equally likely to grow, shrink or show no change. Fibroids regress after the menopause due to the reduction in circulating oestrogen. Each fibroid is of monoclonal origin.

Clinical Features

History:

Fifty per cent are asymptomatic and discovered only at pelvic or abdominal examination. Symptoms are related more to the site than the size.

- Menstrual problems: menorrhagia occurs in 30%, although the timing of menses is usually unchanged. Intermenstrual loss may occur if the fibroid is submucosal or polypoid. Fibroids are common in the perimenopausal woman and may be incidental: menstrual problems may also be the result of hormonal irregularities or malignancy.

- Pain: fibroids can cause dysmenorrhoea. They seldom cause pain, unless torsion, red degeneration or, rarely, sarcomatous change occur.

- Other symptoms: large fibroids pressing on the bladder can cause frequency and occasionally urinary retention, those pressing on the ureters can cause hydronephrosis; other pressure effects may also be felt. Fertility can be impaired if the tubal ostia are blocked or submucous fibroids prevent implantation. Intramural fibroids not distorting the cavity also reduce fertility though the mechanism is unclear.

Examination:

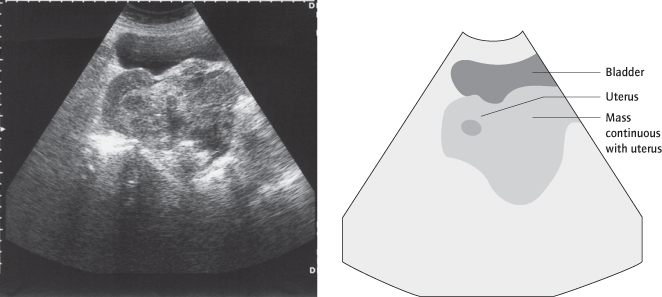

A solid mass may be palpable on pelvic or even abdominal examination. It will arise from the pelvis and be continuous with the uterus. Multiple small fibroids cause irregular ‘knobbly’ enlargement of the uterus.

Symptoms of Fibroids

None (50%)

Menorrhagia (30%)

Erratic/bleeding (IMB)

Pressure effects

Subfertility

Natural History/Complications of Fibroids

Enlargement can be very slow. Fibroids stop growing and often calcify after the menopause, although the oestrogen in hormone replacement therapy (HRT) may stimulate further growth. In mid-pregnancy they may enlarge. Pedunculated fibroids occasionally undergo torsion, causing pain.

‘Degenerations’ are normally the result of an inadequate blood supply: ‘red degeneration’ is characterized by pain and uterine tenderness; haemorrhage and necrosis occur. In ‘hyaline degeneration’ and ‘cystic degeneration’ the fibroid is soft and partly liquefied.

Malignancy:

Around 0.1% of fibroids are leiomyosarcomata [→ p.29]. This may be the result of malignant change or de novo malignant transformation of normal smooth muscle.

Complications of Fibroids

| Torsion of pedunculated fibroid | |

| Degenerations: | Red (partic. in pregnancy) |

| Hyaline/cystic | |

| Calcification (postmenopausal and asymptomatic) | |

| Malignancy: | Leiomyosarcoma |

Fibroids and Pregnancy

Premature labour, malpresentations, transverse lie, obstructed labour and postpartum haemorrhage can occur. Red degeneration is common in pregnancy and can cause severe pain. Fibroids should not be removed at Caesarean section as bleeding can be heavy. Pedunculated fibroids may tort postpartum.

Hormone Replacement Therapy and Fibroids

HRT [→ p.113] can cause continued fibroid growth after the menopause. Treatment is as for premenopausal women or the HRT is withdrawn.

Investigations

To Establish Diagnosis:

Ultrasound is helpful but magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or laparoscopy may be required to distinguish the fibroid from an ovarian mass (Figs 3.3, 3.4). Adenomyosis can exist as a fibroid-like mass, differentiated by MRI. Hysteroscopy or hysterosalpingogram (HSG) is used to assess distortion of the uterine cavity, particularly if fertility is an issue.

To Establish Fitness:

The haemoglobin concentration may be low as a result of vaginal bleeding, but also high as fibroids can secrete erythropoietin.

Treatment

Asymptomatic patients with small or slow-growing fibroids need no treatment. The risk of malignancy is small enough not to warrant routine removal or monitoring. Larger fibroids that are not removed should be serially measured by examination or ultrasound because of the remote possibility of malignancy.

Medical Treatment

Tranexamic acid, non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs or progestogens are often ineffective when menorrhagia [→ p.12] is due to fibroids but may be worth trying as a simple first-line treatment. Gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists cause temporary amenorrhoea and fibroid shrinkage by inducing a temporary menopausal state. Side effects and bone density loss restrict their use to only 6 months, usually near the menopause or to make surgery easier and safer. However, concomitant use of ‘add-back’ HRT may prevent such effects without causing enlargement, allowing longer administration. Once the GnRH agonist is stopped and oestrogen levels return to normal then fibroids will return to their previous size. GnRH agonist treatment is not appropriate for women trying to conceive due to the anovulation induced and return of the fibroids with drug cessation. Consequently, surgery is usually used to manage fibroids under these circumstances.

Is the Fibroid Malignant?

Uncommon, but more likely if:

Pain and rapid growth

Growth in postmenopausal woman not on hormone replacement therapy (HRT)

Poor response to gonadotrophin-releasing hormone (GnRH) agonists

Surgical Treatment

Hysteroscopic Surgery

The fibroid polyp or small (up to 3 cm) submucous fibroid that is causing menstrual problems or subfertility can be resected at hysteroscopy (transcervical resection of fibroid (TCRF)) [→ p.129]. Pretreatment with GnRH agonist for 1–2 months will shrink the fibroid, reduce vascularity and thin the endometrium so making resection easier and safer.

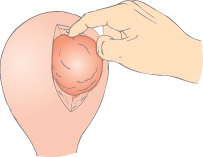

Myomectomy

Fibroids can be removed from the uterus: open or laparoscopic myomectomy (Fig. 3.5). Blood loss may be heavy (risk of blood transfusion, or hysterectomy to save life) and small fibroids can be missed, causing problems to recur. Myomectomy is performed if medical treatment has failed but preservation of reproductive function is required. Open (but not laparoscopic as conversely the fibroid excision becomes more difficult) operations can be preceded by 2–3 months’ treatment with GnRH analogues to shrink the fibroid and reduce vascularity. Peroperative injection of vasopressin directly into the myometrium reduces blood loss (Cochrane 2009: CD005355). Adhesions can form at the site of myomectomy which, if affecting the endometrial cavity or fallopian tubes/ovaries, significantly reduce fertility. Endometrial cavity adhesions can be very difficult to treat. If the endometrial cavity is opened during myomectomy, or if the fibroids are multiple and/or large, then Caesarean section is indicated in future pregnancies because of an increased risk of uterine rupture during labour.

Radical: Hysterectomy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree