7% of all babies are premature (<37 weeks) and 1% are extremely premature (<28 weeks) or very low birthweight (VLBW<1500 g). Premature babies can survive from 23–24 weeks gestation, although mortality is high (25% survival at 23 weeks, 45% at 24 weeks) and only 25% of those that survive at these gestations will be free of disability. Beyond 30–32 weeks the prognosis is excellent. Premature infants are at risk of complications such as hypothermia, hypoglycaemia and difficulty feeding, which are common to IUGR babies too.

Premature babies need care on a special care baby unit (SCBU) or neonatal intensive care unit (NICU). Incubators provide warmth and humidity to prevent hypothermia and protect the skin, which is thin, red and transparent and does not provide an adequate barrier to heat and fluid loss. Feeding problems are common. A mature suck–swallow pattern does not develop until 34 weeks, so premature babies need to be fed via a nasogastric tube. Very sick premature babies, or those with IUGR or asphyxia, may be at increased risk of necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) and are therefore given intravenous parenteral nutrition. Premature babies are at risk of infection, either acquired from the mother during delivery or from the hospital environment and to brain injury (see below).

Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Respiratory Distress Syndrome

Pneumonia, pneumothorax, cardiac failure and congenital lung malformation can all cause respiratory distress in preterm infants but by far the commonest cause is respiratory distress syndrome (RDS) due to surfactant deficiency.

Signs of RDS include tachypnoea, intercostal recession, cyanosis and expiratory ‘grunting’. CXR shows a ‘ground glass’ appearance due to alveolar collapse with an air-bronchogram. RDS is caused by lack of surfactant, a phospholipid which reduces alveolar surface tension. Surfactant production is not mature until about 35–36 weeks, although the stress of labour usually stimulates production, and RDS is therefore usually self-limiting, lasting 5–7 days. Corticosteroids administered antenatally to at risk mothers reduce RDS by stimulating surfactant production. IUGR babies are physiologically ‘stressed’ and tend to get less severe RDS due to endogenous corticosteroid release.

Management involves optimizing oxygenation and supporting respiration, either with continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) via nasal prongs, or by mechanical ventilation. Surfactant can be administered via an endotracheal tube. This treatment has reduced the mortality of RDS by over 40%. 20% of babies with RDS develop chronic lung disease of prematurity (bronchopulmonary dysplasia) which if severe may require home-oxygen therapy.

Necrotizing Enterocolitis

Necrotizing Enterocolitis

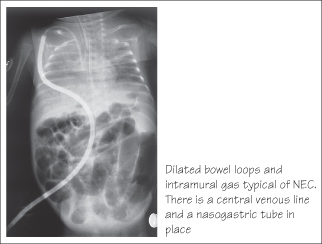

This serious complication is due to impaired blood flow to the bowel. Mucosal ischaemia allows gut microorganisms to penetrate the bowel wall causing a severe haemorrhagic colitis. Breast milk is protective, but increasing milk feeds (especially formula feeds) too rapidly is a risk factor for NEC, as is a patent arterial duct (PDA). NEC presents with acute collapse, abdominal distension, bile-stained vomiting and bloody diarrhoea. An abdominal radiograph may show gas in the bowel wall or portal veins. Management involves stopping feeds, supporting the circulation and antibiotics. Laparotomy is required if perforation occurs. Complications include intestinal stricture and short bowel syndrome.

Retinopathy of Prematurity

Retinopathy of prematurity (ROP) is common in very premature infants, occurring in up to 35% of VLBW babies. In most cases it requires no treatment but in about 1% of these babies it causes blindness. ROP is caused by proliferation of new blood vessels in an area of relative ischaemia in the developing retina. Oxygen toxicity is one cause although there may also be a genetic predisposition. At-risk infants should be screened for ROP by an ophthalmologist. If detected, laser ablation can be used to prevent the risk of retinal detachment and blindness.

Brain Injury

Brain Injury

Preterm infants are at risk of brain injury and this is the most important factor affecting their long-term prognosis. Periventricular leucomalacia, large intraventricular haemorrhage and posthaemorrhagic hydrocephalus are the most important lesions causing disability.

- Intraventricular haemorrhage (IVH) occurs in up to 30% of VLBW. Haemorrhage develops in the floor of the lateral ventricle and ruptures into the ventricle. In a small minority the haemorrhage involves the white matter around the ventricle by a process of obstructive venous infarction. This carries a high risk of hemiplegic cerebral palsy (see Chapter 42). IVH may be asymptomatic and is diagnosed by cerebral ultrasound scan.

- Posthaemorrhagic hydrocephalus occurs in 15% of severe IVH and may require insertion of a ventriculo-peritoneal shunt.

- Periventricular leucomalacia is caused by ischaemic damage to the periventricular white matter. It is less common than IVH, but is the commonest cause of cerebral palsy in surviving infants. PVL is particularly likely where there has been chorioamnionitis, severe hypotension or in monozygotic twins. The prognosis is worse if cystic change develops, with 80% developing cerebral palsy.

Neurodevelopment

There is an increased incidence of learning difficulties in extremely preterm infants. Attention difficulties are common, and subtle problems in higher functioning may not manifest until school age.

KEY POINTS

- 7% of infants are born before <37 weeks. 1% are extremely premature <28 weeks.

- Complications relate to organ immaturity and include hypothermia, hypoglycaemia and surfactant deficient RDS.

- Premature babies are at increased risk of cerebral palsy due to intracranial haemorrhage and white matter injury.

- Perinatal infection (chorioamnionitis) is an important risk factor for preterm labour and for cerebral palsy.