The Physical Examination

Shoshana Melman

GENERAL CONSIDERATIONS

Performing the Physical Examination

The physical examination of a child is as much an art as a scientific procedure. The goal is to make the examination as productive and nontraumatic as possible.

To minimize fear in young children, conduct most of the physical examination with the child sitting on the parent’s lap or nestled against his or her shoulder. If the child appears fearful, talk with the parent first so that the child has a chance to study you. Speak quietly, using a friendly tone of voice. Move gently and slowly, avoiding loud, sudden movements.

The physical examination is routinely presented and written in standard (adult) order, although it may not be carried out in that sequence. Children about 8 years and older can usually be examined easily in standard adult order, but with younger patients it is important to examine the most critical areas first, before the child cries. Always start with observation. Next, in a young child with a specific presenting complaint, it is often helpful to examine the corresponding organ system. In a young child with no specific complaints, palpate the fontanelles and then auscultate the heart and the lungs. Wait until the end of the examination to check the most threatening areas (e.g., the ears and the oral cavity).

Special Concerns

Mental Status

Since children often cannot vocalize their symptoms, their overall mental status is an essential clue to their degree of illness. Will the child smile or play? Observe interactions with parents or siblings. Be careful to differentiate a child who is simply tired from one who is lethargic (difficult to arouse). Similarly, distinguish the cranky child who comforts easily from one who is truly irritable and inconsolable.

Hydration Status

Physical findings consistent with dehydration include an increased heart rate, decreased blood pressure, sunken fontanelle, dry mucous membranes, decreased skin turgor, and increased capillary refill time (> 2 seconds).

VITAL SIGNS AND STATISTICS

Temperature

Body temperatures are more labile in children than in adults and can be raised depending on the time of day (e.g., in the late afternoon) or following vigorous activity, excitement, or even eating.

A child’s normal oral temperature is similar to an adult’s, typically about 98.6 °F. The rectal temperature is typically approximately 1° higher than the oral equivalent, and an axillary temperature (the least accurate method) is typically about 1° lower. Study results regarding the reliability of tympanic thermometers have been mixed; they are often used in low-risk older children.

Pulse Rate

In an infant, palpate for pulse rate over the brachial artery. In an older child or adult, the wrist is generally the optimal location. Pulse rate is usually 120 to 160 beats per minute in the newborn and steadily declines as the child grows. A typical teenager’s pulse rate would be 70 to 80 beats per minute.

Respiration Rate

The most accurate measurements are obtained while the patient is asleep. In infants and young children, breathing is mostly diaphragmatic; the respiratory rate can be determined by counting movements of the abdomen. In older children and adolescents, chest movement should be directly observed. Table 2-1 summarizes the normal pediatric respiratory rates.

TABLE 2-1 Normal Pediatric Respiratory Rates (Respirations/min) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Blood Pressure

To obtain an accurate blood pressure measurement, patient relaxation is especially critical. Explain to a young child that the “balloon” will squeeze his arm and encourage him to watch the display.

Cuff width is also important. Choose a cuff width that covers 50% to 75% of the upper arm length. A too-narrow cuff may artificially increase the blood pressure reading.

If you are concerned about the possibility of heart disease, check blood pressure in all four extremities. Compare blood pressure measurements with standard norms for age and sex.

Length (Height)

To obtain a length measurement, place the infant on a firm table. Hold the baby’s feet against a stationary board, keeping the knees straight, and bring a movable upright firmly against the baby’s head to measure the infant’s recumbent length.

Children > 2 years can be measured with the child standing erect. The child should be positioned with feet flat, eyes looking straight ahead, and occiput, shoulders, buttocks, and heels against a vertical measuring board.

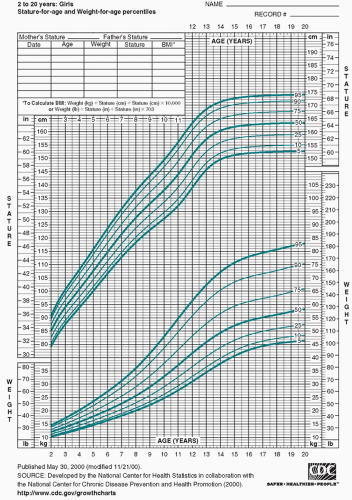

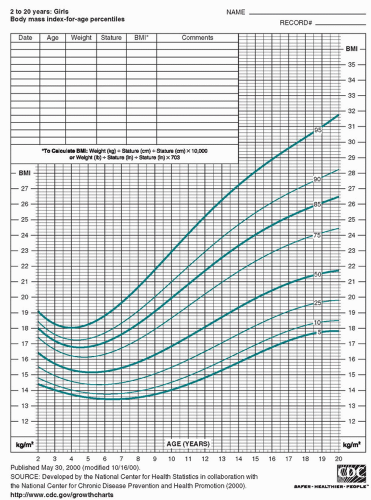

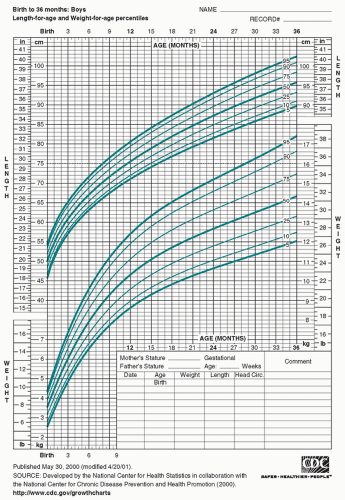

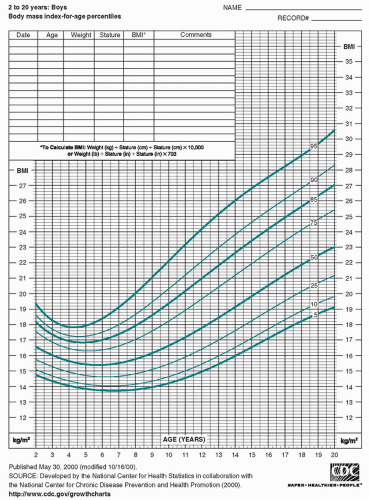

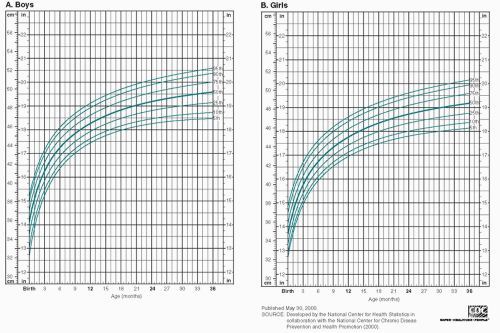

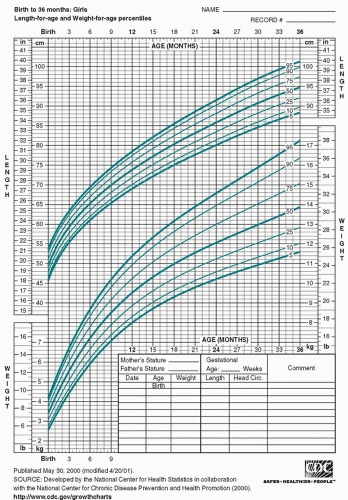

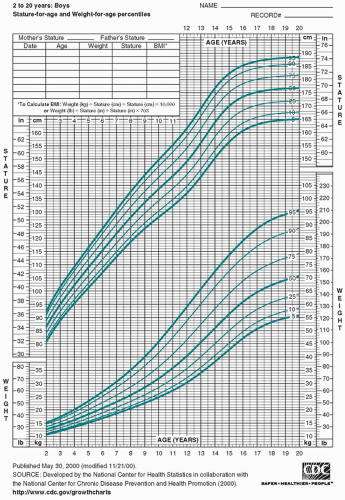

Figure 2-1 shows the National Center for Health Statistics percentiles for physical growth in girls and boys from birth through the age of 20 years. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends that health care providers for U.S. children use World Health Organization growth charts to monitor growth for infants and children aged 0 to 2 years and use Centers for Disease Control and Prevention growth charts to monitor growth for children aged 2 years and older.

Weight

Routinely weigh infants unclothed. For patients in whom small variations in weight are important, it is helpful to consistently use a single scale, preferably at the same time of day.

The growth charts in Figure 2-1 include body mass index (BMI) (wt/ht2). This number is used in patients >2 years to determine whether weight is appropriate for height. By plotting BMI for age, health care providers can achieve early identification of patients at risk for being overweight/obese.

HEAD

Head Circumference

Start your examination of the head by measuring the head circumference at the maximum point of the occipital protuberance posteriorly and at the midforehead anteriorly. Microcephaly (small head size) could result from abnormalities such as craniosynostosis (premature fusion of the cranial sutures) or congenital TORCH (toxoplasmosis, other infections, rubella, cytomegalovirus, and herpes simplex) infection. Macrocephaly (large head size) could be caused by problems such as hydrocephalus or an intracranial mass. Figure 2-2 presents normal head circumferences.

FIGURE 2-1 National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Clinical Growth Charts. A. Girls, birth to 36 months: Length-for-age and weight-for-age. (continued) |

FIGURE 2-1 (Continued) E. Boys, 2-20 years: Stature-for-age and weight-for-age percentiles. (continued) |

Skull Depressions

Depressions of the skull may represent fractures but are most commonly sutures (i.e., membranous tissue spaces that separate the skull bones) and fontanelles (i.e., areas where the major sutures intersect; also known as “soft spots”). The cranial sutures usually overlap in the newborn because of intrauterine pressure. Sutures that are widely palpable after 5 to 6 months of age may indicate hydrocephalus.

The anterior fontanelle is typically about 1 to 4 cm in diameter at birth and usually closes between the ages of 4 and 26 months. The posterior fontanelle is usually 0 to 2 cm in diameter at birth and generally closes by 2 months of age. When describing fontanelles, mention their status (open or closed), size, and fullness. If palpated while the baby is sitting, a tense or elevated fontanelle may reflect increased intracranial pressure. A depressed fontanelle can be a sign of dehydration.

Head Shape

Observe the shape of the child’s head. Areas of flatness, especially in the occipital or parietal regions, may be caused by lying too long in one position and may occur in an infant suffering from neglect, prematurity, or mental retardation. Frontal bossing may be a sign of rickets. Areas of localized head swelling could be caused by neoplastic, infectious, or traumatic processes.

Newborns often have caput succedaneum (a soft swelling of the occipitoparietal scalp) caused by injury during birth. Cephalohematoma, another birth injury, is a swelling caused by subperiosteal hemorrhage involving one of the cranial bones. In cephalohematoma, the swelling does not cross the suture lines as it does in caput succedaneum.

Percussion and Auscultation of the Head

Percussion of the head may reveal Macewen sign (a resonant sound in children with closed fontanelles that indicates increased intracranial pressure) or Chvostek sign (contraction of the facial muscles in response to percussion just below the zygomatic [cheek] bone). Chvostek sign can be found in normal newborns as well as in children with hypocalcemic tetany. Percussion over the parietal bone may produce a “cracked-pot sound,” a normal finding prior to suture closure.

Auscultation of the head for bruits is not particularly useful until late childhood. Systolic or continuous bruits may be heard in the temporal area until the age of 5 years. Abnormal conditions that may be associated with bruits include

arteriovenous malformation, cerebral vessel aneurysms, brain tumors, and coarctation of the aorta.

arteriovenous malformation, cerebral vessel aneurysms, brain tumors, and coarctation of the aorta.

Inspection of the Hair and Scalp

The child’s hair should be assessed for quantity, color, texture, and infestations. Causes of alopecia include fungal infections (tinea capitis), stress (telogen effluvium), and excessive hair pulling (trichotillomania).

Dry, coarse hair may be a sign of hypothyroidism, and fine, thin hair may be seen in children with homocystinuria. In children with pediculosis capitis (head lice), close inspection reveals small adherent nits (eggs).

EYES

The eye examination is very important, providing information about the eyes and, in many cases, systemic problems. It is usually counterproductive (not to mention unkind) to try to pry a child’s eye open. Instead, distract the patient with a toy or other object whenever possible to gain cooperation. A recalcitrant newborn can be encouraged to open his eyes by having an assistant gently rotate the baby from side to side while supporting him vertically (i.e., under the arms).

Assessment of the Eyes

Range of Motion and Orientation

Check for full range of motion by attracting the child’s attention with a toy or piece of equipment. Strabismus (a condition in which the eyes do not move in a parallel manner) often manifests as esotropia (turning in of an eye) or exotropia (turning out of an eye). The following tests can be performed to test for strabismus:

Corneal light reflection. Have the child focus on a small light. When the child is looking at the light, the reflection of the light from each cornea should be symmetrically placed. Asymmetries suggest the presence of strabismus.

Cover-uncover test. The child focuses on a light, and one eye is covered and then uncovered. If either eye moves, strabismus may be present.

Distance Between the Eyes

Observe the distance between the eyes, which can be documented as either the inner canthal distance or the interpupillary distance. Hypotelorism (abnormal closeness of eyes) is frequently found with holoprosencephaly sequence, maternal phenylketonuria, trisomy 13, and trisomy 20p. Hypertelorism (increased distance between the eyes) is frequently associated with a wide number of syndromes, including Apert syndrome, DiGeorge sequence, fetal hydantoin effects, Noonan syndrome, trisomies 8 and 9p, and absence of the corpus callosum.

Nystagmus and “Setting Sun” Sign

Observe for nystagmus (rhythmical movements of the eyeballs) and “setting sun” sign (in which the eyes constantly appear to be looking downward). Nystagmus may be physiologic or it may be found with early loss of central vision, labyrinthitis, multiple sclerosis, intracranial tumors, or drug toxicity. “Setting sun” sign may be seen with hydrocephalus or intracranial tumor, but it may also be transiently noted in some healthy infants.

General Appearance

Check for an abnormal upward, outward eye slant and for epicanthal folds (vertical folds of skin over the medial portions of the eyes). Both can be associated with Down syndrome.

Assessment of the Individual Eyes

Visual Inspection

The following should be noted:

Pupil size and reaction to light—both direct and consensual

Condition of the eyelids—potential abnormalities include edema (swelling), erythema (redness), drooping, or the presence of masses

Hazy corneas—causes include glaucoma and inborn errors of metabolism

Injected or inflamed conjunctivae

Icteric sclerae

Brushfield spots on the irises—small white spots frequently associated with Down syndrome

Excess tearing—often caused by congenital obstruction of the nasolacrimal duct

Funduscopic Examination

In infants, a minimal funduscopic evaluation consists of evaluation of the red reflex: the ophthalmoscope is set at 0 diopters. At a distance of approximately 1 ft away from the patient, a reddish orange color (generally brightest in Caucasians) should be visible through the pupil. Leukocoria, a white pupillary reflex, can indicate serious disease, including cataracts, retinal detachment, or retinoblastoma. Inflammation or opacity of the cornea should be noted. Finally, if possible, the optic disc and vessels should be examined, ruling out fundal lesions and papilledema.

Vision Screening

The infant’s vision should be screened using a brightly colored object. Note the infant’s response and ability to track an object. Formal vision testing (often using the Snellen E Chart) can usually start at about 3 years of age (see Chapter 3, “Developmental Surveillance”).

EARS

External Examination

Rashes that favor the postauricular area include seborrheic dermatitis, measles, and rubella. Pain on gentle traction of the pinna or tragus can signal external otitis.

Otoscopic Examination

Before examining the tympanic membrane, ensure that any uncooperative child is well restrained. One simple method is to have the parent firmly hold the supine child’s raised arms against either side of the head. This also allows easy access for the oral examination that follows.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree