Background

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death due to gynecologic malignancy and the fifth most common cause of cancer deaths in developed countries. Recent evidence has indicated that the most common and lethal form of ovarian cancer originates in the distal fallopian tube, and recommendations for surgical removal of the fallopian tube (bilateral salpingectomy) at the time of other gynecologic surgeries (particularly hysterectomy and tubal sterilization) have been made, most recently by the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Objective

We sought to assess the uptake and perioperative safety of bilateral salpingectomy at the time of hysterectomy and tubal sterilization in the United States and to examine the factors associated with increased likelihood of bilateral salpingectomy.

Study Design

The Nationwide Inpatient Sample was used to identify all girls and women 15 years or older without gynecologic cancer who underwent inpatient hysterectomy or tubal sterilization, with and without bilateral salpingectomy, from 2008 through 2013. Weighted estimates of national rates of these procedures were calculated and the number of procedures performed estimated. Safety was assessed by examining rates of blood transfusions, perioperative complications, postprocedural infection, and fever, and adjusted odds ratios were calculated comparing hysterectomy with salpingectomy with hysterectomy alone.

Results

We included 425,180 girls and women who underwent inpatient hysterectomy from 2008 through 2013 representing a national cohort of 2,036,449 (95% confidence interval, 1,959,374–2,113,525) girls and women. There was an increase in the uptake of hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy of 371% across the study period, with 7.7% of all hysterectomies including bilateral salpingectomy in 2013 (15.8% among girls and women retaining their ovaries). There were only 1195 salpingectomies for sterilization, thus no further comparisons were possible. In the girls and women who had hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy, there was no increased risk for blood transfusion (adjusted odds ratio, 0.95; 95% confidence interval, 0.86–1.05) postoperative complications (adjusted odds ratio, 0.97; 95% confidence interval, 0.88–1.07), postoperative infections (adjusted odds ratio, 1.26; 95% confidence interval, 0.90–1.78), or fevers (adjusted odds ratio, 1.33; 95% confidence interval, 1.00–1.77) compared with women undergoing hysterectomy alone. Younger age, private for-profit hospital setting, larger hospital size, and indication for hysterectomy were all associated with increased likelihood of getting a hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy in women retaining their ovaries.

Conclusion

Our results suggest that hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy is significantly increasing in the United States and is not associated with increased risks of postoperative complications.

Introduction

Ovarian cancer is the leading cause of death due to gynecologic malignancy and the fifth most common cause of cancer deaths in developed countries. In the United States and Canada, there are ∼25,000 new diagnoses and ∼16,000 deaths from the disease annually. In both general population and high-risk women (BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers), screening for ovarian cancer is not recommended, as no mortality benefit has been demonstrated even with strict adherence to screening protocols, which has prompted a push to explore methods of primary prevention. In the last decade, we have dramatically improved our understanding of the 5 main histological subtypes of ovarian carcinoma: high-grade serous cancer (HGSC), low-grade serous cancer, endometrioid cancer, clear cell cancer, and mucinous cancers. HGSC is the most common histotype, accounting for approximately 70% of invasive ovarian carcinomas, and research has demonstrated that the distal fallopian tube is the probable site of origin of the majority of HGSCs.

Given these findings, recommendations were made regarding removal of the fallopian tube during common gynecologic surgeries in women who had completed childbearing. In September 2010 the ovarian cancer research team recommended to all gynecologic surgeons in the province of British Columbia, Canada, that, when operating on women at general population risk for ovarian cancer, they should consider: (1) performing bilateral salpingectomy at the time of hysterectomy (even when the ovaries are being preserved); and (2) performing bilateral salpingectomy in place of tubal ligation for permanent sterilization. This was followed by a similar recommendation from the Society of Gynecologic Oncology of Canada, and later by the Society of Gynecologic Oncology. Most recently the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) published a statement supporting the recommendation that surgeons and patients discuss removing the fallopian tubes during a hysterectomy without oophorectomy, and consider a bilateral salpingectomy when counseling women about laparoscopic sterilization methods. Among BRCA1 and BRCA2 mutation carriers, risk-reducing bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (BSO) remains the recommended prevention approach.

Previous research has indicated a significant increase in uptake of bilateral salpingectomy in the United States. Hicks-Courant reported a 77% increase in the rate of any bilateral salpingectomy in the United States from 2000 through 2013. Research examining hysterectomy with adnexal procedures reported a near quadrupling of the rate of hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy from 1998 through 2011. Herein, we use data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) to present national statistics on hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy and salpingectomy for sterilization in the United States from 2008 through 2013, and add to the current literature by examining whether there are increased rates of perioperative and postoperative complications associated with bilateral salpingectomy. We also examine the factors associated with having a hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality NIS data set, which is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient care database in the United States. The NIS contains a random sample of approximately 20% of discharges (>7 million hospital stays annually). The NIS also provide trend weights. Applying the trend weights make the estimates representative of all hospital discharges within the United States allowing for representation of >36 million hospitalizations annually and 97% of the US population. Institutional ethics approval for this project was not required because it fell under Article 2.4 of the “Research Exempt from Research Ethics Board review” section of the TriCouncil Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans 2.

We identified procedures using the Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) services and procedure categories (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville MD). We included all women who underwent a hysterectomy (CCS code 124), tubal ligation (CCS code 121), bilateral oophorectomy (CCS code 119), or bilateral salpingectomy (CCS code 665) alone from 2008 through 2013. Each procedure is coded separately, so a patient undergoing a hysterectomy with BSO would have a code for each procedure. This time period was selected to represent an era prior to the launch of an educational campaign proposing salpingectomy in women at low risk for developing ovarian cancer who were undergoing other procedures, eg, hysterectomy, for the prevention of ovarian cancer (September 2010) and after , with 2013 being the last year complete data were available. We excluded patients who were not coded as being female, were <15 years old, or had a diagnosis of gynecologic cancer. Patients were stratified based on a combination of their CCS code (a system that categorizes patient diagnoses and procedures into a manageable number of clinically meaningful categories) and their International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification ( ICD-9-CM ) codes. We stratified into 5 groups: (1) girls and women who underwent hysterectomy with no concomitant oophorectomy or salpingectomy (hysterectomy alone); (2) girls and women who underwent hysterectomy with BSO; (3) girls and women who underwent hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy; (4) girls and women who underwent tubal ligation; and (5) girls and women who had bilateral salpingectomy alone with a diagnosis code indicating the procedure was for sterilization ( ICD-9-CM V25.2). We examined the surgical approach to the hysterectomy stratifying women into 5 groups: abdominal ( ICD-9-CM 68.3, 68.39, 68.4, 68.49, 68.9), laparoscopic ( ICD-9-CM 68.31, 68.41, 68.51), vaginal ( ICD-9-CM 68.5, 68.59), radical ( ICD-9-CM 68.6, 68.61, 68.69, 68.7), and robotic (any hysterectomy code along with ICD-9-CM 17.4x). We also used diagnostic codes to examine indications for hysterectomy, including endometriosis ( ICD-9-CM 617), leiomyoma ( ICD-9-CM 218), benign ovarian or uterine neoplasms ( ICD-9-CM 219, 220), abnormal bleeding ( ICD-9-CM 626), pelvic organ prolapse ( ICD-9-CM 618), pelvic inflammatory disease ( ICD-9-CM 614.9), and hydrosalpinx ( ICD-9-CM 614.1). To assess operative and perioperative complications, we examined differences in hospital length of stay, rates of blood transfusions ( ICD-9-CM 99.0x), complication of procedures ( ICD-9-CM 998.x), postoperative infection ( ICD-9-CM 998.5), and postprocedural fever ( ICD-9-CM 780.62).

Statistical analysis

We estimated the nationally representative number of girls and women undergoing each of our procedures of interest from 2008 through 2013 using the trend weights to facilitate comparisons across time and to report how the sample numbers reflect the national numbers. We calculated the percentage change in the number of each procedure performed across the study period. After examining the number of each of the procedures of interest, we decided not to pursue further comparisons between our tubal ligations and salpingectomy for sterilization groups due to very low numbers of girls and women undergoing salpingectomy for sterilization. This may reflect the fact that many tubal sterilization procedures are done as outpatient procedures and not included in the NIS data set, which is supported by the fact that 85% of the girls and women in our data set with a diagnostic code for sterilization had a labor and delivery code in the same hospital stay, suggesting their inpatient stay was for childbirth rather than the tubal sterilization procedure. Thus, we focused only on hysterectomy patients in more detail. We examined patient characteristics across the 3 categories of hysterectomy (hysterectomy alone, hysterectomy with BSO, and hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy) and used χ 2 tests to examine differences across the groups. To examine operative and perioperative complications, we ran logistic regressions adjusting for patient age, indication for hysterectomy, surgical approach, and number of chronic conditions. We obtained adjusted odds ratios (aOR) for blood transfusion, procedural complications, postoperative infection, and postprocedural fever, adjusting for patient age, indication for hysterectomy, surgical approach, and number of chronic conditions. We were unable to assess hospital readmissions because the NIS data are collected at the level of the discharge and not the patient.

To assess the associations between patient sociodemographics, number of chronic conditions, and hospital level factors and likelihood of having a hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy, we ran a logistic regression model among all girls and women undergoing hysterectomy and among the subset of girls and women undergoing hysterectomy without oophorectomy. All analyses were completed using software (Stata, Version 13; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted using the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality NIS data set, which is the largest publicly available all-payer inpatient care database in the United States. The NIS contains a random sample of approximately 20% of discharges (>7 million hospital stays annually). The NIS also provide trend weights. Applying the trend weights make the estimates representative of all hospital discharges within the United States allowing for representation of >36 million hospitalizations annually and 97% of the US population. Institutional ethics approval for this project was not required because it fell under Article 2.4 of the “Research Exempt from Research Ethics Board review” section of the TriCouncil Policy Statement: Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans 2.

We identified procedures using the Clinical Classifications Software (CCS) services and procedure categories (Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality, Rockville MD). We included all women who underwent a hysterectomy (CCS code 124), tubal ligation (CCS code 121), bilateral oophorectomy (CCS code 119), or bilateral salpingectomy (CCS code 665) alone from 2008 through 2013. Each procedure is coded separately, so a patient undergoing a hysterectomy with BSO would have a code for each procedure. This time period was selected to represent an era prior to the launch of an educational campaign proposing salpingectomy in women at low risk for developing ovarian cancer who were undergoing other procedures, eg, hysterectomy, for the prevention of ovarian cancer (September 2010) and after , with 2013 being the last year complete data were available. We excluded patients who were not coded as being female, were <15 years old, or had a diagnosis of gynecologic cancer. Patients were stratified based on a combination of their CCS code (a system that categorizes patient diagnoses and procedures into a manageable number of clinically meaningful categories) and their International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision, Clinical Modification ( ICD-9-CM ) codes. We stratified into 5 groups: (1) girls and women who underwent hysterectomy with no concomitant oophorectomy or salpingectomy (hysterectomy alone); (2) girls and women who underwent hysterectomy with BSO; (3) girls and women who underwent hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy; (4) girls and women who underwent tubal ligation; and (5) girls and women who had bilateral salpingectomy alone with a diagnosis code indicating the procedure was for sterilization ( ICD-9-CM V25.2). We examined the surgical approach to the hysterectomy stratifying women into 5 groups: abdominal ( ICD-9-CM 68.3, 68.39, 68.4, 68.49, 68.9), laparoscopic ( ICD-9-CM 68.31, 68.41, 68.51), vaginal ( ICD-9-CM 68.5, 68.59), radical ( ICD-9-CM 68.6, 68.61, 68.69, 68.7), and robotic (any hysterectomy code along with ICD-9-CM 17.4x). We also used diagnostic codes to examine indications for hysterectomy, including endometriosis ( ICD-9-CM 617), leiomyoma ( ICD-9-CM 218), benign ovarian or uterine neoplasms ( ICD-9-CM 219, 220), abnormal bleeding ( ICD-9-CM 626), pelvic organ prolapse ( ICD-9-CM 618), pelvic inflammatory disease ( ICD-9-CM 614.9), and hydrosalpinx ( ICD-9-CM 614.1). To assess operative and perioperative complications, we examined differences in hospital length of stay, rates of blood transfusions ( ICD-9-CM 99.0x), complication of procedures ( ICD-9-CM 998.x), postoperative infection ( ICD-9-CM 998.5), and postprocedural fever ( ICD-9-CM 780.62).

Statistical analysis

We estimated the nationally representative number of girls and women undergoing each of our procedures of interest from 2008 through 2013 using the trend weights to facilitate comparisons across time and to report how the sample numbers reflect the national numbers. We calculated the percentage change in the number of each procedure performed across the study period. After examining the number of each of the procedures of interest, we decided not to pursue further comparisons between our tubal ligations and salpingectomy for sterilization groups due to very low numbers of girls and women undergoing salpingectomy for sterilization. This may reflect the fact that many tubal sterilization procedures are done as outpatient procedures and not included in the NIS data set, which is supported by the fact that 85% of the girls and women in our data set with a diagnostic code for sterilization had a labor and delivery code in the same hospital stay, suggesting their inpatient stay was for childbirth rather than the tubal sterilization procedure. Thus, we focused only on hysterectomy patients in more detail. We examined patient characteristics across the 3 categories of hysterectomy (hysterectomy alone, hysterectomy with BSO, and hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy) and used χ 2 tests to examine differences across the groups. To examine operative and perioperative complications, we ran logistic regressions adjusting for patient age, indication for hysterectomy, surgical approach, and number of chronic conditions. We obtained adjusted odds ratios (aOR) for blood transfusion, procedural complications, postoperative infection, and postprocedural fever, adjusting for patient age, indication for hysterectomy, surgical approach, and number of chronic conditions. We were unable to assess hospital readmissions because the NIS data are collected at the level of the discharge and not the patient.

To assess the associations between patient sociodemographics, number of chronic conditions, and hospital level factors and likelihood of having a hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy, we ran a logistic regression model among all girls and women undergoing hysterectomy and among the subset of girls and women undergoing hysterectomy without oophorectomy. All analyses were completed using software (Stata, Version 13; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX).

Results

There were 484,732 girls and women in the NIS data set who underwent inpatient hysterectomy from 2008 through 2013. We excluded 64 girls and women who were age <15 years at the time of their hysterectomy, 1082 patients who were not coded as being female, and 58,406 girls and women who had diagnostic codes indicating they had a gynecologic cancer, leaving 425,180 included in our study. After applying the trend weights for the NIS sample, these 425,180 girls and women represent a national cohort of 2,036,449 (95% confidence interval [CI], 1,959,374–2,113,525) girls and women who underwent inpatient hysterectomy from 2008 through 2013. This consisted of 934,712 (95% CI, 896,569–972,856) hysterectomies alone; 1,049,457 (95% CI, 1,007,776–1,091,138) hysterectomies with BSO; and 52,280 (95% CI, 49,148–55,413) hysterectomies with bilateral salpingectomy. The NIS data included 338,741 girls and women who had a tubal ligation and 1195 who had only a bilateral salpingectomy with no other procedures, 288 with a corresponding sterilization code . After weighting, this represented 1,623,932 (95% CI, 1,544,411–1,703,454) tubal ligations, 5777 (95% CI, 5305–6250) salpingectomies alone, and 1397 (95% CI, 1125–1669) salpingectomies with a corresponding sterilization code. Due to the small numbers of salpingectomies for sterilization, we did not pursue any further comparisons.

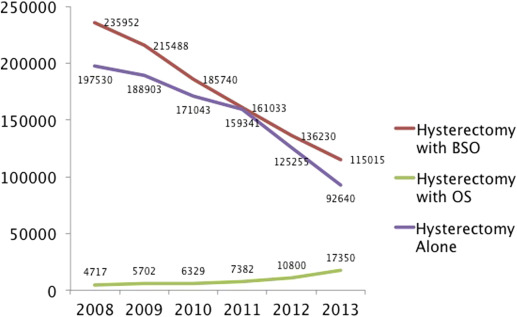

The Figure illustrates the number of hysterectomies annually with and without BSO and bilateral salpingectomy. The total number of hysterectomies performed decreased from a high of 438,199 (95% CI, 395,255–481,142) in 2008 to a low of 225,005 (95% CI, 214,911–235,099) in 2013 representing a 49% decrease in annual number of hysterectomies in the United States from 2008 through 2013. The number of hysterectomies with BSO decreased 51% going from 235,952 (95% CI, 212,371–259,532) in 2008 to 115,015 (95% CI, 109,434–120,596) in 2013. There were comparably few hysterectomies with bilateral salpingectomy; however, they increased significantly across the study period from 4717 (95% CI, 3964–5470) in 2008 to 17,350 (95% CI, 16,031–18,668) in 2013 representing a 371% increase across the study period.

The girls and women in our 3 hysterectomy groups differed significantly in terms of all characteristics measured, including number of chronic conditions, all indications for hysterectomy, and surgical approach ( Table 1 ). Girls and women who underwent hysterectomy with BSO were significantly older, were more likely to be white, had slightly lower income, and had significantly more chronic conditions than those undergoing hysterectomy alone or hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy. They were also more likely to be covered by Medicare. The hysterectomy alone and hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy groups differed in terms of indication for the hysterectomy ( Table 1 ). Girls and women undergoing hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy were more likely to have endometriosis and hydrosalpinx than girls and women undergoing hysterectomy alone. Women having hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy were less likely to have pelvic organ prolapse than those having hysterectomy alone. Surgical approach also differed across the groups, with hysterectomy with BSO more often performed abdominally and hysterectomy with bilateral salpingectomy more often performed laparoscopically.