Chapter 26 The newborn infant

TRANSITION TO EXTRA-UTERINE LIFE

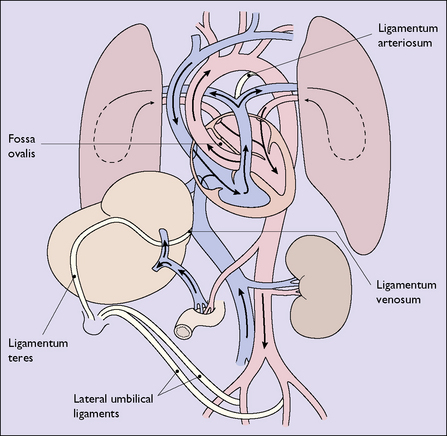

Changes in the pattern of blood circulation

With the closure of the ductus venosus, the foramen ovale and the ductus arteriosus, the adult pattern of circulation of the blood is established (Fig. 26.1; compare with Fig. 4.1, p. 29).

PERINATAL HYPOXIA

Any condition occurring during late pregnancy or labour that reduces the oxygen available to the fetus will predispose it to cardiorespiratory and neurological depression at birth. These conditions have been mentioned when discussing the at-risk fetus in pregnancy and labour (see p. 152).

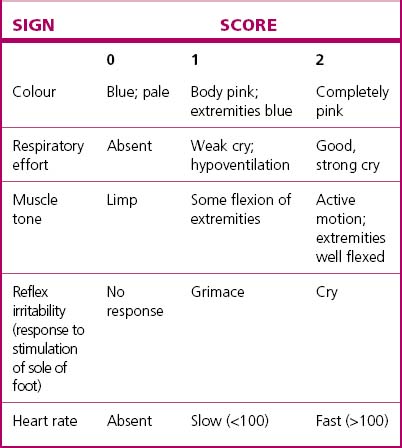

The severity of cardiorespiratory and neurological depression around the time of birth can be assessed by the Apgar scoring system (Table 26.1) or by the pH and/or blood lactate of umbilical artery blood. Both are useful in managing the immediate problem but are relatively poor indicators of long-term outcome.

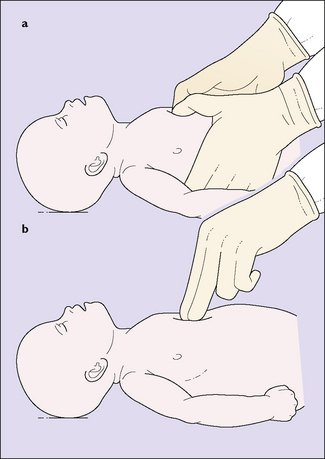

The basic resuscitation of the newborn is described on page 77 (see Fig. 8.15). The most important step in resuscitation is to initiate ventilation with intermittent positive-pressure respiration; current evidence suggests that ventilation using air (21% oxygen) should be the initial step for term babies, with oxygen being added only if hypoxia persists despite adequate ventilation. Initial ventilation should be with a mask and inflating device; failure to initiate spontaneous breathing within 2–5 minutes may require endotracheal intubation – but only if a person skilled in this technique is present. If the infant remains bradycardic (HR <60) despite adequate ventilation, the circulation should be supported by external cardiac massage (Fig. 26.2) and, possibly, endotracheal 1: 10 000 adrenaline 0.3–1.0 mL/kg. Once the umbilical vein is cannulated a further 0.1–0.3 mL/kg dose of adrenaline is given, and if there is no response further doses of adrenaline 0.1– 0.3 mL/kg can be given at 3–5-minute intervals.

BIRTH INJURIES

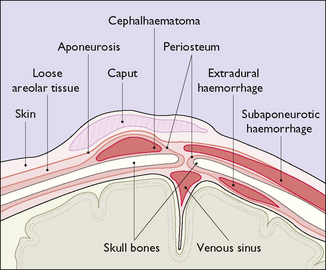

Cranial injuries (Fig. 26.3)

Subaponeurotic (subgaleal) haemorrhage

Subaponeurotic haemorrhage, while rare, occurs most commonly after a traumatic vacuum extraction (see p. 195–197) and may result in significant blood loss from the infant’s circulation. Occasionally the bleeding is very rapid and life-threatening and requires urgent blood transfusion. Frequent observation for diffuse head swelling following vacuum extraction is mandatory.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree