Chapter 35 Endometriosis and adenomyosis

ENDOMETRIOSIS

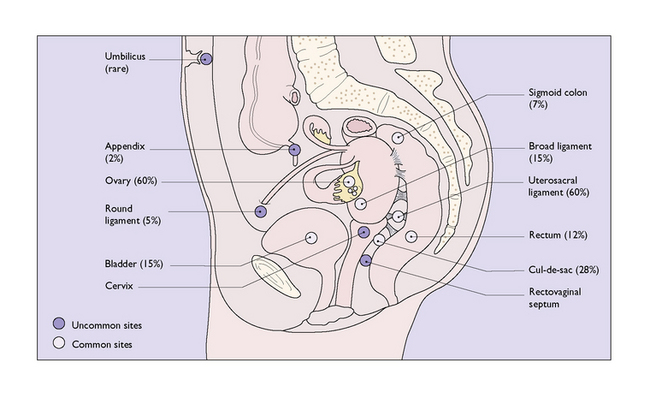

Endometriosis denotes presence of functioning endometrial tissue in an abnormal location, in other words, outside the uterus (Box 35.1). The locations and the approximate chance of the lesion affecting the organ or structure are shown in Figure 35.1.

Box 35.1 Endometriosis

| What is it? | Functioning endometrial tissue which is outside the uterus, most commonly found on the uterosacral ligament and ovary |

| Aetiology | |

| Prevalence | |

| Diagnosis | Can only be diagnosed at laparoscopy and confirmed by biopsy |

| Symptoms | Frequently symptomless, the main reasons for investigation being menstrual irregularities, premenstrual ‘dysmenorrhoea’ pain, non-cyclical pelvic pain, dyspareunia and infertility |

| Management | Depends on the woman’s age, her desire for pregnancy, the severity of the symptoms and the extent of the lesions Hormonal – to prevent the cyclical ovarian production of oestrogen, and to a lesser extent progesterone |

| Outcome | Five years after either hormonal or surgical treatment has ceased endometriosis recurs in 20–40% of women |

Pathology

Rupture or leakage of material from even small cysts is not uncommon. The released inspissated blood is very irritating, with the result that multiple adhesions surround the cysts. The ectopic endometrium and stromal cells also tend to infiltrate adjacent tissues, leading to more pelvic adhesions and fixation (Fig. 35.2

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree