The Head, Face, and Neck

Craig S. Derkay and Michael J. Cunningham

CONGENITAL ANOMALIES OF THE HEAD AND NECK

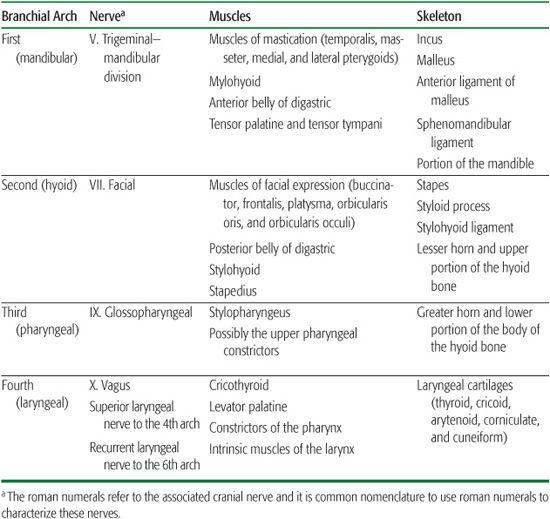

The critical period of cervicofacial growth and differentiation occurs between weeks 4 through 8 of embryologic development.1 The beginning of this stage is characterized by the appearance of the frontonasal process—the precursor of the forebrain and upper face—with development soon thereafter of the optic and otic vesicles; the nasal placodes; the primitive mouth, or stomodeum; and five ridges on the ventrolateral surface of the embryonic head, which is known as the branchial system. Many of the symmetrically paired skeletal and neuromuscular structures of the head and neck arise from the first (mandibular), second (hyoid), third (pharyngeal), and fourth (laryngeal) arches of this fetal branchial system (Table 372-1). The skull, facial, and neck bones have begun to ossify by the end of the eighth fetal week, which coincides with a recognizable human embryonic face with easily discernible ears, eyelids, cheeks, nose, and upper and lower lips.

Table 372-1. Derivatives of the Pharyngeal Arches and Their Innervation

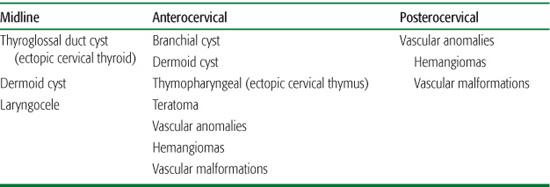

Most of the congenital anomalies of the face and neck are believed to arise from altered or arrested growth during this critical developmental stage. Such anomalies may initially manifest at birth as an asymptomatic palpable mass or a sinus or fistula opening; they alternatively may remain unnoticed until secondary infection causes acute presentation later in childhood.2 The anatomic location of such lesions often suggests their embryologic origin3 (Table 372-2).

BRANCHIAL ANOMALIES

BRANCHIAL ANOMALIES

Lesions of the anterolateral neck are often of branchial system origin. Each of the four mesodermal branchial arches were separated from one another by an external cleft of ectodermal origin and by an internal pouch of endodermal origin with a thin epithelial plate separating cleft and pouch. Branchial cleft anomalies are classified by the likely arch of origin, with second branchial anomalies being most common.4 They form either sinuses, fistulas, or cysts. A sinus tract with either an external or internal opening represents a vestigial cleft or pouch. Branchial cleft sinuses with external openings to the skin are typically associated with the first and second arches. Second branchial anomalies can present as enlarging neck masses or as small draining sinuses in the lateral neck at the border of the sternomastoid muscle (eFigs. 372.1 and 372.2  ). Third and fourth arch anomalies, sometimes referred to as piriform fistulas, are quite rare. They usually present as recurrent neck abscesses or suppurative thyroiditis, almost exclusively on the left side.5 While excision of these piriform fistulas and the associated mass/tract is curative, recent reports have indicated at least short-term benefits from cautery of endoscopically demonstrated fistula tracts in the piriform sinus.6 Recurrence of branchial anomalies after surgical excision is more common after multiple infections, so early removal of these lesions is usually recommended.7 Treatment is complete excision of the cyst and/or sinus tract. First branchial anomalies are less common, with tracts that involve the ear canal or the facial nerve. First branchial anomalies can present as sinus tracts or masses near the ear or parotid gland. Excision of these anomalies usually requires dissection of the facial nerve to prevent injury (Fig. 372-1).8 Third and fourth arch anomalies, sometimes referred to as piriform fistulas, are quite rare. They usually present as recurrent neck abscesses or suppurative thyroiditis, almost exclusively on the left side.5 While excision of these piriform fistulas and the associated mass/tract is curative, recent reports have indicated at least short-term benefits from cautery of endoscopically demonstrated fistula tracts in the piriform sinus.6

). Third and fourth arch anomalies, sometimes referred to as piriform fistulas, are quite rare. They usually present as recurrent neck abscesses or suppurative thyroiditis, almost exclusively on the left side.5 While excision of these piriform fistulas and the associated mass/tract is curative, recent reports have indicated at least short-term benefits from cautery of endoscopically demonstrated fistula tracts in the piriform sinus.6 Recurrence of branchial anomalies after surgical excision is more common after multiple infections, so early removal of these lesions is usually recommended.7 Treatment is complete excision of the cyst and/or sinus tract. First branchial anomalies are less common, with tracts that involve the ear canal or the facial nerve. First branchial anomalies can present as sinus tracts or masses near the ear or parotid gland. Excision of these anomalies usually requires dissection of the facial nerve to prevent injury (Fig. 372-1).8 Third and fourth arch anomalies, sometimes referred to as piriform fistulas, are quite rare. They usually present as recurrent neck abscesses or suppurative thyroiditis, almost exclusively on the left side.5 While excision of these piriform fistulas and the associated mass/tract is curative, recent reports have indicated at least short-term benefits from cautery of endoscopically demonstrated fistula tracts in the piriform sinus.6

Table 372-2. Congenital Malformations of the Neck

The external opening of a congenital sinus or fistula tract is often detectable at birth; noninfected tracts may secrete a mucuslike material. In contrast, branchial cysts may enlarge slowly and may not be evident until the second or third decade of life. Cyst presentation early in childhood is often due to acute, painful enlargement associated with an upper respiratory tract infection. Recurrent neck abscesses, particularly in the left thyroid region, should raise concern that a vestigial branchial pouch is maintaining an internal opening into the oropharynx or hypopharynx.

Although branchial anomalies typically occur as isolated entities, anomalous branchial system development does occur in association with some craniofacial and multiorgan syndromes, such as oculo-auriculo-vertebral spectrum (hemifacial microsomia or Goldenhar syndrome) and branchio-oto-renal (BOR) syndrome.

THYROID ANOMALIES

THYROID ANOMALIES

Midline neck masses raise suspicion of alternative developmental anomalies, most commonly of thyroid origin. Such thyroid anomalies include thyroglossal duct cysts and comparatively rare ectopic cervical thyroids. The thyroid gland originates as a diverticulum from the floor of the mouth. During embryologic descent into the inferior neck, the thyroid gland remains connected to the pharynx by an embryonic duct that eventually involutes. The persistence of a portion of this duct causes the thyroglossal duct cyst, whereas arrest in the normal descent of the gland results in an ectopic thyroid. The majority of thyroglossal duct cysts present in children and adolescents as asymptomatic or inflamed neck masses at or below the level of the hyoid bone (Fig. 372-2). These cysts comprise up to 13% of excised neck masses in children in one series and over 50% of surgically treated congenital neck cysts in another series.9,10 They arise from expansion of persistent remnants of the thyroglossal duct tract, which usually disappears between the 5th and 10th embryonic weeks. While most of these cysts occur close to the thyroid notch or the hyoid bone, they can occur anywhere from the tongue base to the thyroid isthmus. Thyroglossal duct cysts present most commonly as asymptomatic masses, but they can become infected with enlargement and overlying skin erythema. Preoperative evaluation should include imaging to exclude the diagnosis of ec-topic solitary thyroid tissue by confirming the presence of a normal thyroid gland. The operation described by Sistrunk—excising the cyst, the thyroglossal duct tract, a portion of the central hyoid, and a core of tongue base tissue—remains the standard of care with low rates of recurrence (eFig. 372.3  ).11,12

).11,12

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree