Background

Depression has been associated with symptom amplification, functional impairment, and lower incontinence-specific quality of life in women with urinary incontinence. Although depression has been shown to impact both subjective and objective outcomes after many different surgeries, there are limited data on the effects of major depression on postoperative outcomes after antiincontinence surgery.

Objective

The purpose of this study was to determine whether major depression affects urinary incontinence severity and quality of life after midurethral sling surgery.

Study Design

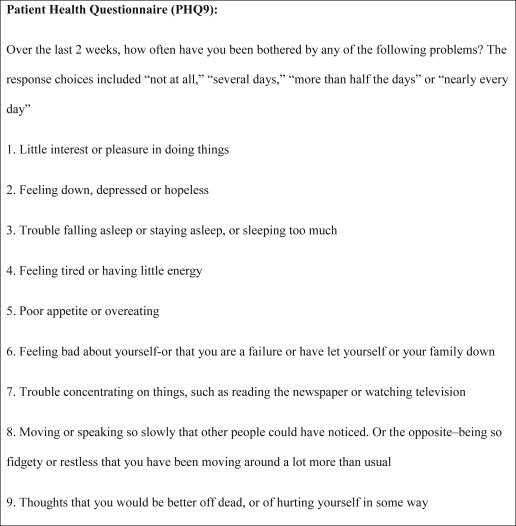

This was a secondary analysis of the Trial of Midurethral Slings. Participants were assigned randomly either to a retropubic or transobturator sling for stress urinary incontinence. Each was classified as having major depression or not by the validated depression screening Patient Health Questionnaire-9. Pre- and postoperative urinary incontinence severity (which was assessed by the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire), urinary incontinence-specific quality of life (which was assessed by the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire and the Urinary Distress Inventory), and sexual function (which was assessed by the Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire) was compared between groups at baseline and at 12 months.

Results

Five hundred twenty-six patients were included: 79 patients (15%) had major depression before surgery; 447 patients (85%) did not. Baseline incontinence severity was higher in women with major depression than in those without (International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire, 14.7 ± 4.1 vs 12.9 ± 4.0; P < .001). Similarly, baseline quality of life and sexual function were worse in depressed women than in nondepressed women (Incontinence Impact Questionnaire, 235.6 ± 95.8 vs 134.8 ± 89.8; P < .001; Urinary Distress Inventory, 162.7 ± 46 vs 128.6 ± 41.3; P < .001; and Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire–12, 27.2 ± 7.3 vs 33.9 ± 6.4; P < .001). After adjustment for differences between groups, baseline major depression did not negatively affect 12-month incontinence severity or quality of life. However, at 12 months after surgery, despite significant improvement in sexual function scores in depressed women, the 12-month scores were still significantly worse in the major depression group (Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire–12, 34.1 ± 7.1 vs 37.7 ± 6.1; P < .001); multivariable analysis showed independent association of baseline major depression with 12-month sexual function. At 12 months, 83% of those women (66/79) with baseline major depression were no longer depressed.

Conclusion

Women with major depression who are planning surgery for stress urinary incontinence have worse quality of life than nondepressed women. However, women with major depression improve significantly more than those without major depression such that, at 12 months postoperatively, incontinence severity and quality of life are not different between groups. Sexual function is worse before and after the operation for depressed women.

The goal of surgical management of urinary incontinence (UI) is symptom resolution and improvement in a patient’s health related quality of life. Identifying preoperative risk factors that may affect quality of life after surgery for stress UI will assist in shared decision-making about surgery and set better individualized expectations preoperatively. Major depression (MD) is detrimental to quality of life and is very common. In developed countries, there is an 18% lifetime prevalence of a major depressive episode. Among 3000 women who were assessed at 63 outpatient obstetrics-gynecology clinics, MD was present in 4–17%.

Depression has been shown to impact both subjective quality of life and objective outcomes after many different surgeries. In orthopedics, psychologic well-being was shown to predict long-term recovery and likelihood of improvement from knee arthroplasty. In transplant surgery, solid organ transplant recipients with mental distress have a lower quality of life, lower physical health perceptions, and a lower functional capacity after the transplantation compared with transplant recipients without mental distress. In pelvic floor disorders, MD is associated with developing symptoms, with contributing to functional disability, and significantly with impairing quality of life. Several studies have demonstrated an association between UI and depression. Melville et al reported that MD occurs before the onset of incontinence in many women with UI. MD has also been associated with symptom amplification, functional impairment, and lower incontinence-specific quality of life in women with UI.

The primary aim of our study was to determine whether underlying MD affects improvement in UI severity and incontinence-specific quality of life after treatment with a midurethral sling (MUS) compared with nondepressed patients. We hypothesized that baseline MD would impact improvement in quality of life and UI severity negatively after surgical treatment of stress UI.

Materials and Methods

This is a secondary analysis of the Urinary Incontinence Treatment Network Trial of Midurethral Slings (TOMUS). The trial was supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The data reported here were supplied by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Central Repositories. This analysis received exemption by the Cleveland Clinic Institutional Review Board.

The design and primary results of the TOMUS trial have been published previously. Briefly, the TOMUS trial was a multicenter randomized equivalence trial that randomly assigned 597 women with stress UI to either retropubic or transobturator MUS surgery. The primary aim of TOMUS was to compare both objective and subjective 12-month cure rates between each type of MUS. Five hundred sixty-five women completed a 12-month assessment; treatment success was equivalent: 80.8% in the retropubic sling group and 77.7% in the transobturator sling group (3.0% mean difference; 95% confidence interval [CI], –3.6 to 9.6). TOMUS subjects who completed Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9), received MUS surgery, and completed one year of postoperative follow-up providing baseline and 12-month quality of life data were included in this analysis.

All TOMUS participants completed PHQ-9, which corresponds to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed, criteria for the diagnosis of major depressive disorder. The PHQ-9 has been validated in primary care and specialist medical outpatient settings, including gynecology. The PHQ-9 was performed at the same time as the baseline and 12-month questionnaires. Participants were defined as having MD if they answered at least “more than half the days” to 5 of the 9 questions in Figure 1 . One of the 5 affirmative responses must have included “little interest or pleasure in doing things” or “feeling down, depressed, or hopeless.” Any answer more frequent than “not at all” with regards to suicidal ideation was considered affirmative. To be considered depressed, their symptoms had to affect their lifestyle. Participants were asked, “How difficult have these problems made it for you to do your work, take care of things at home or get along with other people?” Affirmative responses were “somewhat difficult,” “very difficult,” or “extremely difficult.” The individual responses to the PHQ-9 questions were then reviewed, and scores were verified for each patient. Patients subsequently were included in the major depressed group who did not have 5 affirmative responses to the questions but reported suicidal ideation “more than half the days” as 1 of their responses. Analyses were conducted with the use of both definitions.

Demographic variables that were considered in this analysis included age, race/ethnicity, education, and marital status. Continuous clinical variables included height, weight, body mass index (BMI), preoperative and postoperative prolapse stages, specific variables from baseline urodynamic testing namely, maximum urethral closure pressure, and lowest Valsalva leak point pressure. We also examined the impact of the presence of detrusor overactivity during urodynamic testing because patients with an urge component (urge or mixed UI) are more likely to have coexistent psychiatric illness and decreased well-being than those with stress incontinence alone. Categoric clinical variables included previous UI surgery, previous pelvic surgery, chronic pelvic pain, menopausal status, hormone replacement therapy, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, diabetes mellitus, and smoking status.

Subjective outcome measures included incontinence severity that was determined by the International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire (ICIQ), incontinence-specific quality of life that was measured by the Incontinence Impact Questionnaire (IIQ) and the Urogenital Distress Inventory (UDI) and sexual function that were measured by the Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire (PISQ-12). Severity and quality-of-life scores were collected at baseline and at 12 months after the operation. The change in each score over the 12-month period was calculated by subtracting the baseline score from the 12-month score. A 5-point change in ICIQ score, a 16-point change in IIQ score, and an 11-point change in UDI score are considered to be minimum clinically important differences in quality-of-life scores. The minimum important difference (MID) for PISQ-12 has not yet been determined, so we estimated that a minimum important clinical difference would be one-half of the baseline standard deviation.

In the TOMUS trial, subjective treatment failure was defined as self-reported leakage by a 3-day voiding diary, self-reported stress UI symptoms, or retreatment of stress UI. Objective treatment failure was defined as a positive stress test, a positive pad test (>15 g/24 hr), or retreatment of stress UI. Retreatment includes behavioral, pharmacologic, and surgical treatment for stress UI symptoms and can occur any time after surgery. We collected the dichotomous data of subjective and objective failures.

Data were managed and analyzed with SAS software (version 9.4; SAS Inc, Cary, NC). Descriptive statistics were used to characterize the overall population and compare incontinence severity, quality of life, and sexual function between our 2 groups. Differences between the depressed and nondepressed groups were tested with χ 2 tests for categoric variables and t tests or analysis of variance for continuous variables. We performed univariate analyses on our severity and quality-of-life questionnaire scores at baseline, at 12 months, and on the change in scores from baseline to 12 months. We then fit multivariable linear regression models for 12-month quality of life and severity scales to control for significant differences between the baseline participant characteristics in the MD and nondepressed groups. Baseline scale score was included as a covariate whether it was significantly different between groups or not. Significant baseline differences ( P ≤ .05) that were identified in the univariate analyses were also included in each of the models as covariates.

For the power analysis, we considered a 5-point change in ICIQ scores at 12 months to be a clinically meaningful improvement in quality of life. The mean change in the ICIQ after surgery in TOMUS was a decrease of 10.3 (±5.0). We also assumed an existing rate of depression in the general population to be 18% in developed countries. With a fixed sample size of 526 subjects, the study had >95% power to detect a clinically relevant difference in incontinence-specific quality of life.

Results

Five hundred twenty-six participants in the TOMUS trial completed quality-of-life questionnaires at baseline and at 12 months and were included in this analysis. Seventy-nine women (15%) had MD before surgery, and 447 women (85%) did not. Thirteen patients who did not have 5 affirmative responses to the questions but who reported suicidal ideation “more than half the days” as 1 of their responses were included in the MD group. Analyses were conducted with the use of both definitions of MD (PHQ-9 score alone vs the inclusion of the suicidal patients who did not meet other PHQ-9 criteria), and the findings of both analyses were similar.

Baseline characteristics of participants with MD and without MD are found in Table 1 . Depressed patients were more likely to be younger (age, 51 ± 11 vs 54 ± 11 years; P = .03), obese (BMI, 34.2 ± 7.0 vs 29.4 ± 6.2 kg/m 2 ; P < .001), diabetic (11 [14%] vs 25 [6%] women; P = .007), and current smokers (18 [23%] vs 46 [10%] women; P = .002). They were less likely to be white (56 [70.9%] vs 368 [82.3%] women; P = .03), attain a higher education level greater than high school (45 [56.9%] vs 319 [71.4%] women; P < .0001), or have “very good” or “excellent” health (20 [25.3%] vs 338 [76.0%] women). Detrusor overactivity was present in 7 of 77 depressed patients (9%; 95% CI, 4–18%) and 54 of 442 nondepressed patients (12% [95% CI, 9–16%]; P = .43). There were no differences in rates of depression or improvement in depression by type of sling.

| Variable | Major depression (n = 79) | No major depression (n = 447) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age, y a | 51 ± 10.5 (28–81) | 54 ± 10.8 (29–87) | .03 |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | .03 | ||

| Hispanic | 12 (15.2) | 49 (11.0) | |

| Non-Hispanic white | 56 (70.9) | 368 (82.3) | |

| Non-Hispanic black | 5 (6.3) | 8 (1.8) | |

| Other | 6 (7.6) | 22 (4.9) | |

| Education level, n (%) | <.0001 | ||

| Less than high school | 10 (12.7) | 18 (4.0) | |

| High school or general educational development diploma | 24 (30.4) | 110 (24.6) | |

| Some college | 33 (41.7) | 157 (35.1) | |

| 4 years of college | 2 (2.5) | 87 (19.5) | |

| Graduate degree | 10 (12.7) | 75 (16.8) | |

| Body mass index, kg/m 2 a | 34.2 ± 7.0 (18.3–55.4) | 29.4 ± 6.2 (18.5–51.2) | <.0001 |

| Current smoker, n (%) | 18 (22.8) | 46 (10.3) | .002 |

| Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 11 (13.9) | 25 (5.6) | .007 |

| Overall health, n (%) | <.0001 | ||

| Excellent | 2 (2.5) | 130 (29.2) | |

| Very good | 18 (22.8) | 208 (46.8) | |

| Good | 39 (49.3) | 85 (19.1) | |

| Fair | 19 (24.1) | 21 (4.7) | |

| Poor | 1 (1.3) | 1 (0.2) | |

| Vaginal deliveries, n b | 2 (0–7) | 2 (0–7) | .74 |

| Menstrual status, n (%) | |||

| Premenopausal | 20 (25.3) | 129 (29.0) | |

| Postmenopausal | 31 (39.2) | 230 (51.7) | |

| Perimenopausal | 22 (27.9) | 73 (16.4) | |

| Not sure | 6 (7.6) | 13 (2.9) | .01 |

| Preoperative pelvic organ prolapse–quantification system stage b | 2 (0–4) | 2 (0–4) | .79 |

| Previous stress urinary incontinence surgery, n (%) | 13 (16.5) | 57 (12.8) | .57 |

| Maximum urethral closure pressure <20 cm H 2 O, n (%) c | 2 (2.9) | 14 (3.4) | .83 |

| Valsalva leak point pressure <60 cm H 2 O, n (%) d | 2 (4.6) | 33 (11.6) | .15 |

| Type of sling, n (%) | .94 | ||

| TVT-O | 21 (26.6) | 114 (25.5) | |

| TOT | 18 (22.8) | 110 (24.6) | |

| TVT | 40 (50.6) | 223 (49.9) |

a Data are given as mean ± SD (range)

b Data are given as median (range)

c Available for 68 depressed and 407 nondepressed participants

d Available for 68 depressed and 407 nondepressed participants.

Table 2 shows changes from baseline to 12 months after surgery in UI severity, incontinence-specific quality of life, and sexual function. Baseline UI severity was higher in women with MD than those without (ICIQ, 14.7 ± 4.1 vs 12.9 ± 4.0; P < .001). Although statistically significant, this difference may not be clinically meaningful, because it does not meet the 5-point MID for ICIQ. The depressed women did have a greater overall improvement over 12 months, with mean change in ICIQ of –11.6 (95% CI, –12.7 to –10.4) vs –10.1 (95% CI, –10.6 to –9.7; P = .002), such that UI severity was similar between the groups at 12 months after MUS surgery. The 12-month ICIQ in subjects with MD was 3.2 ± 4.1 vs 2.8 ± 3.4 ( P = .35) in those without MD. Multivariate analysis confirmed that MD was not associated independently with 12-month UI severity after adjustment for differences between MD and nondepressed groups with the use of baseline ICIQ, age, BMI, ethnicity, smoking status, education level, diabetes mellitus, and overall health ( Table 3 ). Table 3 also addresses the impact of each of the covariates in our multivariate models on UI severity and quality-of-life outcomes. Figure 2 compares both baseline and 12-month UI severity (ICIQ) in participants with MD vs those without MD.

| Variable | Major depression (n = 79) | No major depression (n = 447) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Incontinence severity (International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire) | |||

| Baseline a | 14.7 ± 4.1 | 12.9 ± 4.0 | <.001 |

| 12-Mo a | 3.2 ± 4.1 | 2.8 ± 3.4 | .35 |

| Δ b | –11.6 (–12.7 to –10.4) | –10.1 (–10.6 to –9.7) | .002 |

| Quality of life | |||

| Incontinence Impact Questionnaire | |||

| Baseline a | 235.6 ± 95.8 | 134.8 ± 89.8 | <.001 |

| 12-Mo a | 38.1 ± 67.4 | 16.9 ± 41.7 | <.001 |

| Δ b | –197.5 (–217.8 to –177.2) | –118.0 (–126.5 to –109.4) | <.001 |

| Urogenital Distress Inventory | |||

| Baseline a | 162.7 ± 46.5 | 128.6 ± 41.3 | <.001 |

| 12-Mo a | 5.4 ± 14.4 | 3.9 ± 14.7 | .41 |

| Δ b | –157.3 (–166.6 to –147.9) | –124.7 (–128.6 to –120.8) | <.001 |

| Sexual function (Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire) | |||

| Baseline a | 27.2 ± 7.3 | 33.9 ± 6.4 | <.001 |

| 12-Mo a | 34.1 ± 7.1 | 37.7 ± 6.1 | <.001 |

| Δ b | 6.9 (5.0–8.7) | 3.6 (2.9–4.3) | .001 |

| Covariate | 12-Mo | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire | Incontinence Impact Questionnaire | Urogenital Distress Inventory | Prolapse/Urinary Incontinence Sexual Questionnaire | |||||

| Beta | P value | Beta | P value | Beta | P value | Beta | P value | |

| Baseline scale score | .10 | .009 | .12 | <.001 | .06 | <.001 | .46 | <.001 |

| Baseline depression | .18 | .71 | 9.93 | .12 | –.89 | .66 | –1.85 | .05 |

| Age | .05 | <.001 | .63 | .001 | .07 | .29 | –.10 | <.001 |

| Body mass index | .04 | .09 | –.54 | .11 | –.08 | .44 | .01 | .81 |

| Diabetes mellitus | .9 | .15 | 19.4 | .016 | 2.15 | .41 | –2.16 | .11 |

| Current smoker | –.2 | .68 | 3.79 | .56 | –1.91 | .36 | .91 | .33 |

| Education level a | .86 | .54 | .84 | .84 | ||||

| 4 years of college | –.13 | .81 | 3.88 | .58 | .30 | .90 | –.80 | .40 |

| Some college | –.33 | .49 | –4.69 | .44 | 1.65 | .41 | –.16 | .85 |

| High school/general education development diploma | –.32 | .53 | –4.56 | .49 | .58 | .79 | –.56 | .56 |

| Less than high school | –.9 | .28 | –1.3 | .34 | –1.01 | .77 | .57 | .74 |

| Ethnicity b | .58 | .22 | .17 | .50 | ||||

| Hispanic | –.35 | .50 | 3.26 | .62 | –2.38 | .27 | 1.25 | .15 |

| Non-Hispanic black | .23 | .81 | 17.2 | .19 | 1.9 | .65 | .62 | .74 |

| Other | –.86 | .22 | –12.9 | .15 | –5.72 | .05 | –.26 | .82 |

| Overall health c | .96 | .76 | .54 | .65 | ||||

| Poor | .84 | .74 | 5.14 | .87 | –4.53 | .67 | 3.62 | .31 |

| Fair | .12 | .87 | 6.74 | .46 | 2.17 | .46 | 1.09 | .38 |

| Good | .22 | .66 | 8.10 | .20 | 3.17 | .12 | .64 | .47 |

| Very good | .28 | .47 | 5.65 | .27 | .65 | .69 | –.12 | .85 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree