The following section is a collation of the most commonly seen challenged-child disorders in this author’s practice. A chiropractic approach to each disorder is presented as well as information regarding prognosis, where applicable.

Cerebral Palsy

In the United States, approximately 300,000 individuals manifest this central motor deficit. This syndrome is described as a nonprogressive motor disorder resulting from gestational or perinatal CNS damage and characterized by an impairment of voluntary movement (

13). In this category of neurologic defect there is evidence of a major disturbance of motor function. Numerous causes of cerebral palsy have been investigated; these include physical trauma to the brain at birth (

4) and complications of pregnancy, which include placental complications; abnormalities or presentation (face, brow, and transverse); breech delivery; prolapse of the umbilical cord; and fetal growth retardation, although most term growth-retarded infants develop normally (

1,

14). For low birth weight infants born by breech delivery, the cerebral palsy rate reached almost 5% in a study performed at the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders (

1). Risk factors include child abuse, prematurity, encephalopathy or seizures during the perinatal period, interventricular hemorrhage during the perinatal period, in-utero infections, postnatal meningitis or encephalitis, and hypoxic ischemia (

15).

Intrapartum fetal asphyxia has been implicated as a cause of cerebral palsy, although most cases of cerebral palsy occur in persons without evidence of birth asphyxia or other intrapartum events (

16,

17,

18,

19). Based on formalized review processes, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has not recommended that routine electronic fetal monitoring be used for low-risk women in labor (

20). The Task Force also concluded that there was insufficient evidence to recommend for or against intrapartum electronic fetal monitoring for high-risk pregnant women.

Clinical Signs and Symptoms Cerebral palsy can be grouped into four main categories: spastic, athetoid, ataxic, and mixed forms. Spastic syndromes are most common, representing approximately 70% of the cases (

13). The spastic form of cerebral palsy is characterized by stiff, awkward movements of the affected limbs, muscular hypertonicity, increased deep tendon reflexes, “scissors gait,” and toe-walking of the lower extremities. There may be stiffness and incoordination of the hands and arms, evident in spastic quadriplegia. This form accounts for 30% of cerebral palsy cases, and these children are generally markedly retarded and nonambulatory (

21). Children with spastic hemiplegia or paraplegia frequently have normal intelligence and a good prognosis for social independence (

13). Movements of the extremities are slow, writhing, and involuntary. Emotional tension seems to cause an increase in the motions, which disappear during sleep. Ataxic cerebral palsy is commonly associated with sclerotic lesions of the cerebellum (

21). These patients have difficulty with rapidity of fine movement, weakness, incoordination, and a wide-based gait. The fourth category of cerebral palsy is the mixed form. These are classified most often as spasticity and athetosis and, less often, ataxia and athetosis (

13).

Radiologic Evaluation In addition to the full spine AP and lateral views, a flexion view of the cervical region is beneficial to determine the potential vertebral subluxation. It is often difficult to radiograph these children, and technological assistance is of utmost importance. Because of the patient’s condition, multiple levels of malalignment will usually be present. It is of utmost importance to evaluate the mobility of any motion segment that is determined to need an

adjustment, and all adjustments should be administered in ways that promote improved posture of the spine at both the segmental and global levels.

A subluxation is often detected in the upper cervical region in the patient with cerebral palsy, either as an effect of the disorder or preceding it, but most commonly the antero-superior (AS) condyle (

22). The integrity of the position of the occiput in relationship to the atlas is noted on the neutral lateral, flexion, and AP cervical views. When the condyle slips anterior and superior, the space between the posterior arch of the atlas and the occiput is diminished. The space will remain closed even when the cervical spine is in flexion (

23).

Abnormalities of the brain, identifiable with computed tomography and/or magnetic resonance imaging, include cysts, cerebral atrophy, calcification, tumors, malformation, and stroke (

15).

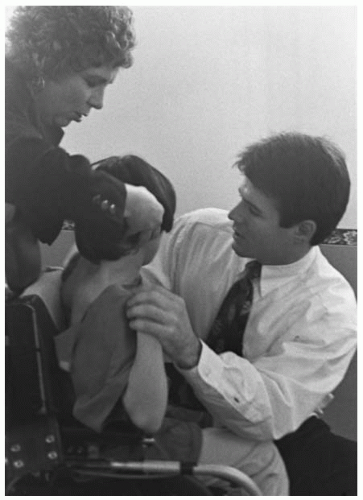

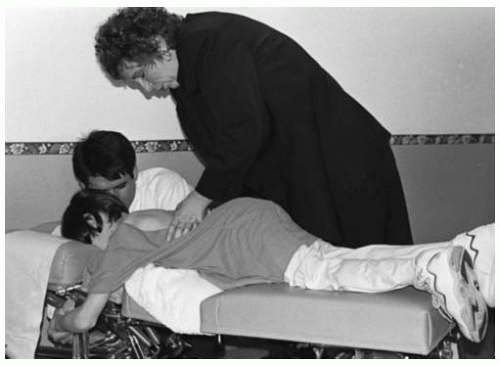

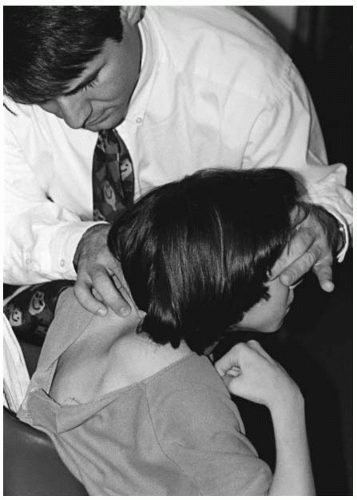

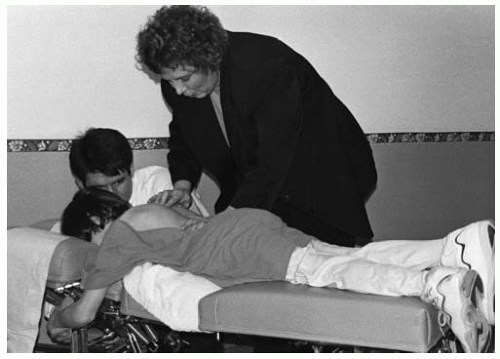

Subluxation Considerations The vertebral subluxation complex can be determined by visual inspection, motion and static palpation, and instrumentation. The correlation of these findings, along with radiographic studies, are optimal for the location and correction of the vertebral subluxation. Special attention should be directed to the upper cervical region; many times the child will present with a “starward gaze” in their head presentation. This could be indicative of an AS condyle misalignment. Careful analysis of this region and the entire spine (including the cranium and pelvis) can produce the specific level of the vertebral subluxation. When correlating the objective findings with the radiological findings, a specific listing can be determined, thus assisting in a specific correction (

Figs. 27-3,

27-4,

27-5,

27-6).

After analyzing the child with cerebral palsy and determining the area of subluxation, a specific adjustment is necessary. The adjusting thrust should be gentle and specific because of the spasticity in many of these children. The thrust should be high velocity and low amplitude.

Cranial and pelvic structures should be checked carefully for subluxation and addressed accordingly. The removal of neurological stresses that may be present can promote a more normal functioning of the nervous system, resulting in improved general resistance.

Prognosis The child with cerebral palsy has many special needs. When caring for these children, special time should be appropriated for not only evaluation and adjusting, but for communication with the children’s caretakers. In this author’s experience, many parents have noted a more positive attitude, relaxation, improved sleep patterns, better coordination, and stronger resistance to stresses. These observations should be evaluated systematically for evidence of efficacy.

Spinal contractures will increase during growth, resulting in scoliosis. This factor will require careful scrutiny by the attending chiropractor. The general course for most patients is functional improvement with time (

15).

General follow-up by the appropriate health care provider is important for patients with cerebral palsy.

Specific areas to be addressed during the child’s growth are the development of contractures, epilepsy, learning disabilities, strabismus, hearing loss, and mental retardation (

15).