Blood Supply and Lymph Drainage

The blood supply is from upper vaginal branches and the uterine artery. Lymph drains to the obturator and internal and external iliac nodes, and thence to the common iliac and para-aortic nodes. Cervical carcinoma characteristically spreads in the lymph and locally by direct invasion into the uterus, vagina, bladder and rectum.

Benign Conditions of the Cervix

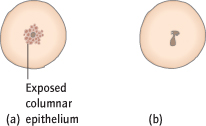

Cervical ectropion (previously called erosion) is when the columnar epithelium of the endocervix is visible as a red area around the os on the surface of the cervix (Fig. 4.2a). This is due to eversion and is a normal finding in younger women, particularly those who are pregnant or taking the ‘pill’. Normally asymptomatic, ectropions occasionally cause vaginal discharge or postcoital bleeding (PCB). This can be treated by freezing (cryotherapy) without anaesthetic, but only after a smear and, ideally, colposcopy has excluded a carcinoma. Exposed columnar epithelium is also prone to infection.

Acute cervicitis is rare but often results from sexually transmitted disease [→ p.74]. Ulceration and infection are occasionally found in severe degrees of prolapse when the cervix protrudes or is held back with a pessary [→ p.57].

Chronic cervicitis is chronic inflammation or infection, often of an ectropion. It is a common cause of vaginal discharge and may cause ‘inflammatory’ smears. Cryotherapy is used, with or without antibiotics, depending upon bacterial culture.

Cervical polyps are benign tumours of the endocervical epithelium (Fig. 4.2b). They are most common in women above the age of 40 years and are seldom larger than 1 cm. They may be asymptomatic or cause intermenstrual bleeding (IMB) or PCB. Small polyps are avulsed without anaesthetic and examined histologically, but bleeding abnormalities must still be investigated [→ p.16].

Nabothian follicles occur where squamous epithelium has formed by metaplasia over endocervical cells. The columnar cell secretions are trapped and form retention cysts, which appear as white or opaque swellings on the ectocervix. Treatment is not required unless symptomatic (rare).

In congenital malformations the uterus and cervix may be absent or varying degrees of duplication may occur [→ p.26].

Premalignant Conditions of the Cervix: Cervical Intraepithelial Neoplasia

Definitions

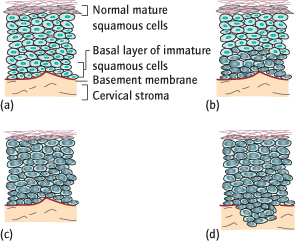

Cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN), or cervical dysplasia, is the presence of atypical cells within the squamous epithelium. These atypical cells are dyskaryotic, exhibiting larger nuclei with frequent mitoses. The severity of CIN is graded I–III and is dependent on the extent to which these cells are found in the epithelium (Fig. 4.3). CIN is therefore a histological diagnosis.

Fig. 4.3 The cervical epithelium and cervical intraepithelial neoplasia (CIN). (a) Normal cervical epithelium; proliferation in basal layer only with small nuclei. (b) CIN I–II: abnormal cells with larger nuclei proliferating in the lower one-third to two-thirds of the epithelium. (c) CIN III: abnormal cells occupying the entire epithelium. (d) Microinvasion: abnormal cells have penetrated the basement membrane.

CIN I (Mild Dysplasia):

Atypical cells are found only in the lower third of the epithelium.

CIN II (Moderate Dysplasia):

Atypical cells are found in the lower two-thirds of the epithelium.

CIN III (Severe Dysplasia):

Atypical cells occupy the full thickness of the epithelium. This is carcinoma in situ; the cells are similar in appearance to those in malignant lesions, but there is no invasion. Malignancy ensues if these abnormal cells invade through the basement membrane.

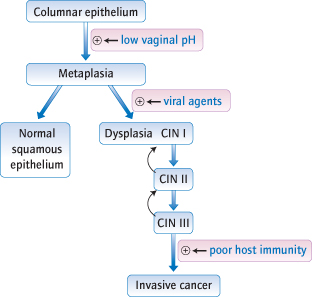

If untreated, about one-third of women with CIN II/III will develop cervical cancer over the next 10 years. CIN I has the least malignant potential: it can progress to CIN II/III, but commonly regresses spontaneously (Fig. 4.4).

Epidemiology

CIN is becoming more common. Ninety per cent of cases of CIN III are in women under 45 years, with peak incidence in those 25–29 years of age.

Aetiology

Human Papilloma Virus (HPV):

The most important factor is the number of sexual contacts, particularly at an early age; CIN is almost unknown in virgins. This is because infection with a HPV is sexually transmitted. Of over 130 different HPV strains, types 16, 18, 31 and 33 are most frequently associated with cervical cancer, though around 13 are considered ‘high risk’. Vaccination against individual viruses reduces the incidence of precancerous cervical lesions, and therefore, potentially, cervical cancer. The vaccine is given before first sexual contact as it has a prophylactic effect, and does not help to treat established CIN (i.e. to children/ young adolescents). A UK national vaccination programme for adolescent girls began in 2008. The vaccine targets HPV types 16 and 18, which are responsible for 75% of cervical cancer cases in the UK. Because cervical cancer affects adult women, it will be many years before the full impact of immunization is seen.

Other Factors:

Oral contraceptive usage and smoking are associated with a slightly increased risk of CIN. Immunocompromised patients (e.g. human immunodeficiency virus [HIV], those on long-term steroids) are also at increased risk and of early progression to malignancy.

Pathology

As the columnar epithelium undergoes metaplasia to squamous epithelium in the transformation zone, exposure to certain HPV results in incorporation of viral deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) into cell DNA. Viral proteins inactivate key cell tumour suppressor gene products and push the cell into a cell cycle. Over time other mutations accumulate and can lead to carcinoma. Viruses also cause changes to hide the infected cell from the immune system. Failure of the immune system to detect and destroy such cells, either because of these cell changes or because of immunosuppression (transplant patient or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome [AIDS]), can result in malignancy.

Diagnosis: Screening for Cervical Cancer

CIN causes no symptoms and is not visible on the cervix. However, the diagnosis identifies women at high risk of developing carcinoma of the cervix who could be treated before the disease develops. Identification of CIN is therefore the principal step in screening for cervical cancer.

Cervical Smears

Screening is performed with cervical smears. These should be performed in all women from the age of 25 years, or after first intercourse if later, and then repeated every 3 years until the age of 49. Between 50 and 64 years of age smears are performed 5-yearly. From the age of 65 only those who have not been screened since age 50 or have had recent abnormal tests are screened. The abnormal smear identifies women likely to have CIN and therefore at risk of subsequent development of invasive cancer. Women younger than 25 years often have abnormal cervical changes but the risk of cervical cancer is very low. Commencing screening at 25 reduces the number of unnecessary recalls and colposcopies. The number of women diagnosed with cervical cancer in the UK has halved since the NHS screening programme was introduced in 1988 and screening now prevents around 5000 deaths per year. Around 80% of eligible women undergo screening.

Method

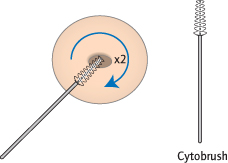

Using a Cusco’s speculum [→ p.6] a brush is gently scraped around the external os of the cervix to pick up loose cells over the transformation zone (Fig. 4.5). The brush tip is broken into preservative fluid, transported to the laboratory, then the fluid is centrifuged and spread on a slide for microscopy (‘liquid-based cytology’ or LBC). LBC has replaced the use of a wooden spatula followed by direct smearing on a slide. The move to LBC as a method of cervical screening has reduced the number of inadequate samples and test recalls from 9% to 2.5%. LBC also allows testing for HPV within the same sample, with subsequent management dependent on the presence or absence of high-risk HPV types (‘HPV triage’).

Results

Smears identify cellular, not histological, abnormalities as only superficial cells are sampled. Cellular abnormalities are called dyskaryosis and graded mild, moderate and severe. Dyskaryosis suggests the presence of CIN, and the grade partly reflects the severity of CIN. Smears are therefore often reported in histological terms; if severe dyskaryosis is seen, for instance, the report may read ‘CIN III’. This does not mean that CIN III is present, merely that a biopsy would be likely to find it.

Women with low-grade cellular abnormalities, such as mild dyskaryosis or borderline changes, previously were invited back for a repeat smear after 6 months. If the abnormality remained then colposcopy was undertaken. From 2011, using HPV triage, women with the low-grade abnormalities have their sample tested for HPV and if a high-risk HPV type is present then colposcopy is arranged. If the sample is negative for a high-risk HPV then the woman is returned to routine 3 to 5-yearly recall.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree