The Breast: Examination and Lesions

Amy D. DiVasta

Christopher Weldon

Brian I. Labow

Breast development in the majority of girls begins between the ages of 8 and 13 years, with an average age of 11.2 years (see Chapter 6). Breast development (thelarche) is often the first sign of beginning puberty.

Although breast cancer is uncommon during the adolescent years, increasing public awareness about the prevalence of breast cancer among women in the United States has made many adolescents exceptionally nervous about breast masses (1,2). This concern may be used constructively to encourage young women to seek routine preventive health assessments and to learn information about normal breast development and the controversies about techniques for screening, including breast self-examination.

Breast Examination

All pediatric and adolescent patients should have a breast examination at the time of their annual physical examination regardless of whether specific complaints are mentioned. Examination of the breasts is initiated during the newborn examination when breast tissue is usually evident secondary to stimulation from maternal hormones. In addition, neonates may have bilateral “white” nipple discharge (“witches’ milk”), which is also due to maternal hormonal stimulation. Infants may have breast problems such as accessory nipples, infection, hemangioma, lipoma, and lymphangioma. For the prepubertal child, the assessment includes inspection and palpation of the chest wall for masses, pain, nipple discharge, or signs of premature thelarche or precocious development (see Chapter 7).

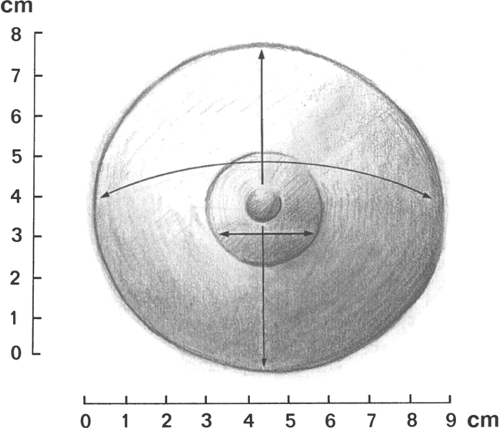

For the adolescent examination, the best time to perform the breast examination is a week or two after a menstrual period. This may include brief observation and palpation in the supine position or, if the patient has a breast complaint, a more comprehensive evaluation. In the latter, the breasts should be inspected while the patient is in the sitting position with her arms at her sides. The size, symmetry, and contour of the breasts are best evaluated in this position. Next, the patient is asked to lie supine with one arm under her head. Breast development is recorded as a Sexual Maturity Rating (SMR), also called Tanner stages B1 to B5 (see Fig. 6-6). If asymmetry or disorders of development are a concern, then exact measurements of the areola, glandular breast tissue, and overall breast size should be included at each examination (Fig. 22-1). For example, one might record the following:

| Areola (cm) | Breast Gland (cm) | Overall (cm) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right | 2.5 | 5 × 6 | 9 |

| Left | 2.4 | 4 × 5 | 8.5 |

The first number in the breast gland figure is the upper-to-lower measurement; the second number is the right-to-left measurement. The overall size is the right-to-left measurement of the border of the fatty tissue of the breast mound.

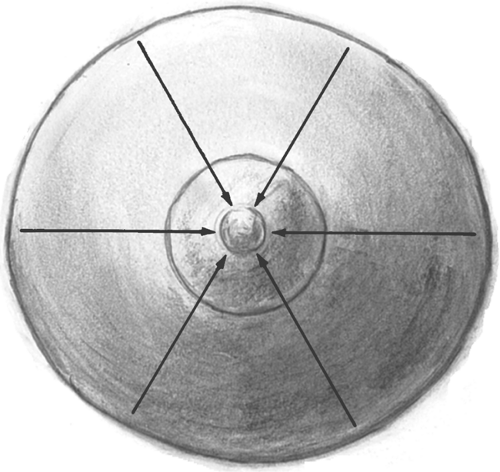

Techniques for Breast Examination

With the patient in the supine position, the entire breast should be palpated systematically including the periphery, tail, and areola. Using a pattern such as concentric circles, consecutive clock times (or “spokes of a wheel,” Fig. 22-2), or parallel lines allows the examiner to palpate the breast tissue in an orderly fashion. In all the methods, the flat finger pads should be moved in a slightly rotatory fashion (about the size of a dime) to feel for abnormalities. Normal glandular tissue has an irregular, granular surface (like tapioca pudding); in contrast, a fibroadenoma feels firm, rubbery, or smooth. The areola should be compressed to assess for the existence of nipple discharge. As part of the overall health assessment, supraclavicular, infraclavicular, and axillary lymph nodes are palpated.

Breast Self-examination

Educating an older adolescent/young adult about the techniques of breast self-examination (BSE) at the time of the breast examination may increase her understanding of the ongoing examination and make her feel more at ease (3). Although adolescents can become quite proficient in learning the necessary techniques, adolescents appear to practice BSE only sporadically and often not at the end of menses, as would be preferred (4). Studies on the value of BSE during adolescence toward promoting lifelong health habits or early detection of breast cancer have been limited (5,6,7,8,9,10). The rationale for teaching BSE has been to contribute to an older adolescent’s understanding and acceptance of her body, enhance her level of comfort with the clinical examination, and provide an opportunity for discussion about women’s health issues (9,11). However, a number of authors have questioned whether early teaching of SBE promotes anxiety, extra visits to health care facilities, and surgery in adolescents; these authors have also queried whether time with a health care provider is better spent with other important risk-reduction strategies, given the extraordinary rarity of breast cancer in the adolescent age group (9,11,12). Thus, teaching BSE techniques is most appropriate for older adolescents and young adult women. The American Cancer Society’s current recommendations state “breast self exam is an option for women starting in their 20s” (13).

Despite studies refuting the value of BSE during adolescence, there is some evidence that self-examination is the primary mode by which adolescent breast masses are detected; Hein and colleagues (3) found that 81% of teenagers with breast masses found them by self-detection. Adolescents should be reassured that cancer is extraordinarily unlikely in their age group. However, a new breast mass that does not disappear after a

menstrual period or that is associated with pain, fever, or erythema should be evaluated in an expedient fashion.

menstrual period or that is associated with pain, fever, or erythema should be evaluated in an expedient fashion.

Figure 22-2. Palpation of the breast. The fingers are moved in a straight line inward going clockwise around the breast. |

With increasing knowledge about predisposing risk factors for breast cancer such as genetic screening and family history, clinicians will be better able to target those patients who possess increased risk for developing breast cancer with appropriate in-office instruction and take-home educational materials. Adolescent women with a history of previous radiation to the chest (who have an increased risk of secondary tumors including cancers of the breast [14–17], with a family history of BRCA1 or BRCA2 gene mutations (18), and with malignancies that may metastasize to the breast should have early teaching of BSE during adolescence.

If the young adult does initiate BSE, it should be performed at the end of each menstrual period. The young woman is instructed to:

Look in the mirror for asymmetry while undressing for a shower.

Examine the breasts while standing in the shower (soap on the hands facilitates the examination).

Reexamine the breasts that night while supine (before going to sleep) with one hand behind the head and a small pillow under the shoulder.

She should be shown how to press gently with the middle three finger pads in one of the systematic approaches described previously. The vertical or horizontal strip method appears to be particularly effective for self-examination (19). Patient information pamphlets, videos, or posters (such as those published by the American Cancer Society or online at www.youngwomenshealth.org) should be available. Beginning the habit of monthly BSE following a normal examination at the office visit can assure the patient that she has a normal baseline for comparison.

Mastalgia (Breast Pain)

Mild breast tenderness (mastalgia) affects up to 40% of reproductive-age young women (20). Mastalgia may be due to premenstrual fibrocystic changes, exercise, or medications, or may be a sign of early pregnancy. Girls initiating oral contraceptives (OCs) may also have mild breast symptoms in the first several months of use, with OCs containing 35 μg of ethinyl estradiol more likely to cause symptoms than 20 μg pills (see Chapter 24). Severe breast tenderness is not a major complaint of healthy adolescents. Breast pain has been shown to be a marker of emotional or physical abuse in some women (21).

The evaluation of mastalgia should include a breast assessment and a pregnancy test. If no clear underlying cause (such as infection) is found, empiric therapy may be started. Despite anecdotal evidence, most case-control studies have not demonstrated an association between benign breast disease and caffeine/methylxanthines (22,23) or a benefit from caffeine-elimination diets (22,24,25). We usually suggest that teenagers with cyclic or noncyclic breast discomfort wear a comfortable supportive bra, use nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) as needed, and, if desired, undertake a 3-month trial of caffeine elimination (coffee, tea, cola, chocolate). For young women active in sports, the utilization of a “sports bra” may be helpful to avoid pain and discomfort. This is particularly helpful to those with large breasts who are involved in activities such as jogging, basketball, and weightlifting.

OCs may improve or worsen breast pain; these disparate effects may be dose related. Teens who experience mastalgia on an OC, may have symptom relief with switching to a 20 μg ethinyl estradiol OC. Berenson and colleagues demonstrated that women taking a 20 μg ethinyl estradiol OC had an odds ratio of breast pain 0.7 times that of a woman not on hormonal therapy (26). Although small trials have shown efficacy of evening primrose oil (500 mg twice daily to 1,000 mg three times a day for 3 months) for treatment of mastalgia (27), a large-scale, randomized clinical trial showed no difference between the key element in evening primrose oil (gamolenic acid, a polyunsaturated fatty acid) and placebo (28). Topical NSAID treatment led

to significant reduction in breast pain without side effects (29). Danazol has proven efficacious in trials of adult women, but frequent side effects preclude its widespread use (30). Similarly, antiestrogen medications, including tamoxifen, may be efficacious if administered during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, but concerns about side effects have to date prevented their use in adolescents (30).

to significant reduction in breast pain without side effects (29). Danazol has proven efficacious in trials of adult women, but frequent side effects preclude its widespread use (30). Similarly, antiestrogen medications, including tamoxifen, may be efficacious if administered during the luteal phase of the menstrual cycle, but concerns about side effects have to date prevented their use in adolescents (30).

Problems of Breast Development

Asymmetry

Asymmetry of the breasts is a common descriptive term that encompasses a variety of diagnoses. Breasts may be asymmetric if one or both are abnormally developed, or if one or both are overdeveloped or underdeveloped. While some degree of breast asymmetry is found in most women, when one breast is distinctly different in terms of shape or greater than a cup size different in volume, the patient or parent may grow concerned and question whether a workup or intervention is required. Since the breast bud may initially appear on one side as a tender, granular lump, patients and parents are often concerned about the possibility of a permanent significant asymmetry or even malignancy in girls in the early stages of breast development. The clinician who sees a young adolescent with breast asymmetry can have a tremendous impact through supportive counseling. It can be helpful to let the 13- or 14-year-old girl with normally developed but asymmetric breasts know that most 18- or 22-year-olds are coping well with the amount of breast asymmetry they have and that most women do not undergo surgical intervention. The clinician should acknowledge that many younger adolescents are most anxious to have their body image equalized and “made normal” as quickly as possible without regard for the possible risks and long-term effects of surgery. Patients should be reassured that malignancy is rarely the cause of breast asymmetry. It should be explained that breast asymmetry may improve with further development, and that nonsurgical options exist to mask asymmetry and allow participation in sports and the wearing of all types of clothes, including swim wear. Once the patient has completed breast development and is cognitively and emotionally ready to discuss surgical options, a referral for surgical intervention may be considered.

The etiologies of most breast asymmetry are unknown, but may be divided into primary and secondary causes. Current theories regarding primary etiologies suggest endocrinologic as well as anatomic causes. Secondary etiologies include iatrogenic sources such as radiation or surgical trauma to the breast bud or developing breast. In addition, secondary deformity from burn or traumatic injury can occur. Two cases of significant asymmetry were reported from sports injuries occurring at Tanner stage 1–2 (31). Exogenous hormone therapy may possibly be associated with abnormal breast development, but more data are needed. A history of exposure to hormones should be sought as part of the initial evaluation.

In all individuals with breast asymmetry, a careful physical examination should be performed. The relative size and shape of each breast, skin changes such as induration or erythema, and nipple-areolar size, position, and pigmentation should be noted. Abnormal masses, cysts, or abscesses should be sought out. Giant fibroadenomas or abscesses may blend into normal breast tissue and may be missed initially during palpation. Abnormally underdeveloped breasts such as in tuberous breast deformity or Poland syndrome should be appropriately diagnosed, and are discussed later in this chapter. The patient’s back should be carefully examined for scoliosis as this may lead to apparent breast asymmetry as well.

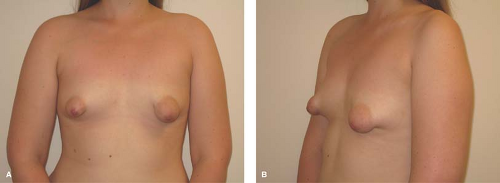

If asymmetry is still marked at age 15 to 18 years and serial measurements show no further increase in size of either breast, patients may wish to explore the option of surgical correction. Surgery may involve augmentation of one or both breasts or reduction of one or both breasts, and in some cases augmentation of one and reduction of the contralateral breast. A plastic surgeon can delineate the risks and benefits of each procedure. Referral to a plastic surgeon familiar with treating adolescents and willing to discuss options without pushing the patient inordinately in the direction of surgery is essential. Success can be quite dramatic, as illustrated in Fig. 22-3.

Macromastia

Adolescents may develop very large breasts (macromastia) that can be associated with a variety of physical and psychological symptoms. The negative impact that this condition can have on the lives of young women should not be underestimated. The most common presenting symptoms include back and neck pain, postural kyphosis, breast discomfort, shoulder soreness from bra straps, and intertrigo. Most patients with symptomatic macromastia also report significant negative alterations in lifestyle, including limited ability to participate in athletic activities, difficulty in finding clothing that fits, and unwanted negative attention (32,33,34,35,36). In one study, the incidence of degenerative spine disorders and the extent of depressive symptoms were correlated with increasing breast weight (37). In most cases the growth occurs over a number of years and the symptoms are progressive. However, there may also be rare cases of rapid unilateral, bilateral, or segmental enlargement during early thelarche (“virginal hypertrophy”). In these cases a workup for other potential etiologies such as juvenile fibroadenomas, nonbreast cancers, and phyllodes tumors should be sought (38,39,40).

Options for treatment include nonsurgical as well as surgical interventions. Many patients with symptomatic macromastia present with bras that provide little support, are ill-fitting, or both. In some cases, a better-fitting, supportive bra may partially or completely correct symptoms. Another frequent finding in this population is obesity. In some studies, 24% to 43.5% of patients with macromastia were overweight or obese (41,42,43,44). While the exact relationship between preadolescent and adolescent obesity and breast hypertrophy is not entirely understood, there is clearly a strong association. Unfortunately, this may result in increasing numbers of symptomatic macromastia patients. While weight reduction has not been proven to treat macromastia (45), it may improve symptoms as well as overall health. Similarly, obese patients with macromastia who ultimately undergo surgery may have more extensive operations and higher complication rates.

Although very few outcome studies have been performed on surgical management of adolescent macromastia, limited data suggest that adolescents undergoing reduction mammaplasty (Fig. 22-4) have a high rate of satisfaction and symptom relief (46,47,48). No ideal age has been reported with respect to the timing of reduction mammaplasty. A patient’s physical and emotional maturity, the severity of symptoms, and parental support are all important factors with respect to when surgery should be considered. In general, most surgeons prefer to allow

breast growth to be near or at completion prior to reduction mammaplasty. A combination of growth charts, consistency in bra size, and years since menarche can be useful clues as to when breast growth is approaching completion. As with all surgical procedures, the risks of reduction mammaplasty must be fully discussed with patients and parents. Although major complications such as hemorrhage or severe infection are rare, scarring including hypertrophic scars, small wound complications, and minor asymmetry are common. In addition, long-term complications such as potential difficulty breastfeeding and alterations in nipple or breast sensation should be discussed.

breast growth to be near or at completion prior to reduction mammaplasty. A combination of growth charts, consistency in bra size, and years since menarche can be useful clues as to when breast growth is approaching completion. As with all surgical procedures, the risks of reduction mammaplasty must be fully discussed with patients and parents. Although major complications such as hemorrhage or severe infection are rare, scarring including hypertrophic scars, small wound complications, and minor asymmetry are common. In addition, long-term complications such as potential difficulty breastfeeding and alterations in nipple or breast sensation should be discussed.

Tuberous Breasts

Tuberous breast deformity is a relatively rare variant of breast development resulting in a spectrum of typically underdeveloped, unusually shaped breasts. Tuberous breasts share the following common features in varying degrees: an elevated inframammary fold; a narrow breast base; hypoplasia, typically of the inferior pole; and glandular “herniation” through the areolae, which are usually enlarged. The condition may be unilateral or bilateral. These features may give the breast(s) the appearance of a tuberous plant root (see Fig. 22-5). The etiology of this condition is unknown. However, this condition is sometimes associated with breasts that develop with the induction of secondary sexual characteristics from exogenous hormones prescribed for treatment of premature ovarian insufficiency, abnormalities of gonadotropin-releasing hormone secretion, or gonadal dysgenesis. This has prompted some to suggest an endocrinologic basis for this condition. The surgical literature also contains descriptions of a distinct fascial plane enveloping and constricting the breast, which has prompted the suggestion that there may be an anatomic basis for this condition as well (49). Patients typically present toward the middle to end of adolescence with a chief complaint of breast asymmetry or underdeveloped breasts. Initial treatment should be supportive reassurance until the patient has reached skeletal and emotional maturity. Many patients are relieved to be given a diagnosis and the knowledge that surgical correction is possible. Plastic surgery can significantly improve breast size, shape, and contour and may require more than a single procedure. It is important to distinguish the patient with tuberous breast deformity from a patient with normally developed small breasts seeking augmentation mammaplasty as the procedure(s) required to treat them, and the anticipated

surgical results can differ widely. Some patients prefer to avoid surgery and thus observation is an acceptable option.

surgical results can differ widely. Some patients prefer to avoid surgery and thus observation is an acceptable option.

Figure 22-4. Adolescent girl with macromastia, prior to surgery (A 1&2) and 2 years following (B 1&2) a 2.2-kg reduction mammaplasty per side. |

Lack of Breast Development

Lack of breast development may occur due to congenital absence of glandular tissue (primary amastia) or a variety of medical or environmental causes. Radiation therapy or trauma to the breast bud, congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), gonadal dysgenesis, hypogonadotropic hypogonadism, an intersex disorder, or 17α-hydroxylase deficiency can all produce subtotal or total agenesis of the breast. Primary amastia is extremely rare and usually unilateral; it may be associated with Poland syndrome (partial or complete absence of the pectoralis major muscle, rib/chest or abdominal wall deformities, symbrachydactyly, or longitudinal deficiency of the upper extremity) (Fig. 22-6). The congenital absence of one or both nipples (athelia) is very rare and may not be associated with absent breast tissue (50).

The evaluation of adolescents with amastia depends on the history and physical findings (see Chapter 8). Any evidence of androgen excess should suggest a disorder such as CAH, an intersex disorder, polycystic ovary syndrome, or an adrenal or ovarian tumor (see Chapter 11). In the absence of any known underlying medical condition, a careful physical examination should be performed to determine whether the underdeveloped breast is truly absent; underdeveloped but normal in shape, contour, and position; or underdeveloped and abnormal in appearance. Adolescents with small but normal breasts and regular menses are healthy young women and deserve reassurance. Augmentation mammaplasty for aesthetic reasons alone in this population should not be performed and breast implants are not approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in this subgroup of patients. However, if the breast is absent or abnormally shaped and underdeveloped, associated findings such as old scars around the areola or findings consistent with Poland syndrome or tuberous breast deformity should be sought. In these patients, breast construction or reconstruction may be considered once skeletal and emotional maturities have occurred, and when contralateral breast growth (if present) has ceased. It is important to distinguish between these patient subgroups as the surgical treatment and outcomes may be quite different.

Premature Thelarche and Precocious Puberty

A discussion of premature thelarche and precocious puberty can be found in Chapter 7.

Accessory Nipples or Breasts

Accessory nipples (polythelia) or breasts (polymastia) occur in 1% to 2% of healthy patients. In some cases, all three components of the breast—glandular tissue, areola, and nipple—are present. More commonly, only a small areola and nipple are found, usually along the embryologic “milk line” between the axillae and groin. The most common sites are the medial chest wall, just inferior to the normal breast tissue, and in the axilla. These abnormalities are usually asymptomatic, and no therapy is usually undertaken, unless at a later date the patient wishes to have the tissue removed for cosmetic reasons. If the patient is symptomatic with pain and/or nipple discharge, the accessory nipple (see Figs. 22-7 and 22-8) or accessory breast (see Figs. 22-9 and 22-10) can be surgically removed. Engorgement of accessory breasts is common during pregnancy and lactation. If no outlet is present, the breast tissue spontaneously involutes within several days to weeks after delivery. There have been reports of fibroadenomas and phyllodes tumors (discussed later) in supernumerary breast tissue (51,52). Despite some conflicting data, it is reasonable to perform renal ultrasonography in an infant with multiple congenital anomalies and supernumerary nipples (53,54).

Breast Discharge

Breast discharge is uncommon during the teen years and can represent many different conditions, including galactorrhea,

ductal ectasia, Montgomery tubercles, infection, or intraductal papillomas. The first step in the evaluation is to characterize the discharge itself, as this can point towards a diagnosis (Table 22-1). The discharge may be milky, purulent, watery, serous, serosanguineous, or bloody. A milky discharge, usually bilateral, is characteristic of galactorrhea, which can be associated with pregnancy/postpregnancy drugs (prescription or illicit), hypothyroidism, chest trauma, or prolactin-secreting tumors. The evaluation of galactorrhea and hyperprolactinemia is discussed in Chapter 9. Purulent discharge suggests infection. Ductal ectasia may present with a sticky, green, serosanguineous, brown, or multicolored discharge from one or both breasts. Serosanguineous discharge may also occur with intraductal papilloma, fibrocystic changes, or rarely, cancer. Bloody nipple discharge in infants has been found to be secondary to ductal ectasia in the majority of cases (55). Most discharges, even bloody ones, do not signify cancer.

ductal ectasia, Montgomery tubercles, infection, or intraductal papillomas. The first step in the evaluation is to characterize the discharge itself, as this can point towards a diagnosis (Table 22-1). The discharge may be milky, purulent, watery, serous, serosanguineous, or bloody. A milky discharge, usually bilateral, is characteristic of galactorrhea, which can be associated with pregnancy/postpregnancy drugs (prescription or illicit), hypothyroidism, chest trauma, or prolactin-secreting tumors. The evaluation of galactorrhea and hyperprolactinemia is discussed in Chapter 9. Purulent discharge suggests infection. Ductal ectasia may present with a sticky, green, serosanguineous, brown, or multicolored discharge from one or both breasts. Serosanguineous discharge may also occur with intraductal papilloma, fibrocystic changes, or rarely, cancer. Bloody nipple discharge in infants has been found to be secondary to ductal ectasia in the majority of cases (55). Most discharges, even bloody ones, do not signify cancer.

Figure 22-8. Status postresection of supernumerary nipple as seen in Fig. 22-7. (Courtesy of Marc R. Laufer, M.D., Children’s Hospital Boston.) |

The evaluation should also include a history of the laterality of the discharge and frequency of occurrence. For a purulent, green, or bloody discharge, suggested evaluation includes Gram stain, cell count, and culture of the discharge; and an ultrasound of the affected breast(s) (55). Cytology of bloody or serosanguineous discharge may also be helpful; the cytologic smear can be obtained on a frosted glass slide sprayed with cytologic fixative. For milky discharge, we recommend measurement of serum HCG, prolactin, estradiol, and thyrotropin-stimulating hormone (TSH).

Figure 22-9. Supernumerary nipple and breast. (Courtesy of Marc R. Laufer, M.D., Children’s Hospital Boston.) |

Figure 22-10. Status postresection of supernumerary nipple and breast as seen in Fig. 22-9. (Courtesy of Marc R. Laufer, M.D., Children’s Hospital Boston.) |

Montgomery Tubercles

Occasionally, a periareolar gland of Montgomery (also called Morgagni tubercles, the small papular projections located at the edge of the areola) will episodically drain clear to brownish fluid through an ectopic opening on the areola for several weeks. One-third of patients may present with a small subareolar lump; the remainder may present with acute inflammation (56). Though the diagnosis is primarily clinical, ultrasound can be used to confirm the clinical suspicion. In the majority of cases, no treatment is necessary, and the discharge and lump will resolve spontaneously over several weeks to months (57). Infections should be treated with oral antibiotics and NSAIDs. If the retroareolar cyst persists, excision may be advisable.

Table 22-1 Potential Etiologies of Breast Discharge | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|