The Adolescent Visit

Charles E. Irwin Jr.

Establishing herself or himself as the primary care physician for an adolescent patient is a formidable task for a pediatrician. A transition interview with patients and their families at approximately 10 years of age is an effective approach for developing a new relationship. During this interview, the pediatrician must inform the parents and the patient about the changing nature of the relationship with the doctor: the need for the doctor to have time alone with the patient, the need to query the young person directly, the need for the patient to be examined alone, and the need of the patient to be encouraged to generate his or her own questions for the doctor. These changes are best done through a discussion of normal adolescence and the need for adolescents to begin to make some decisions in a more independent manner with guidance and support from their families. During this transition interview, the clinician should provide the adolescent and family with some general information regarding the normal physiological and psychosocial changes of adolescence. Depending on the age and psychosocial functioning of the adolescent, the clinician may want to encourage the young person to come to the next clinical visit alone. As the adolescent completes the second decade of life, the pediatrician wants the young adult to be capable of assuming responsibility for his or her own health care.1-3

Confidentiality issues are fundamental to the delivery of health care to adolescents; they need to be able to discuss all matters with the physician openly and honestly. Some physicians may feel uncomfortable with these principles and may want to clarify their position. From the first visit, the physician must assure the young person of the confidentiality of all information within the confines of the legal system. The physician may need to restate this position on confidentiality during the gathering of information in such sensitive areas as sexual behavior and substance use. In the areas of life-threatening disease or behavior (eg, suicide, management of chronic disease), the physician always has the right to intervene on behalf of the patient’s well-being, which generally involves identifying a parent, guardian, or supportive adult who can assist the young person with the problem.4,5

THE HISTORY

THE CLINICAL INTERVIEW

THE CLINICAL INTERVIEW

It is important to create an environment in which the adolescent is able to disclose information regarding his or her health habits. History taking should be guided by the developmental stage of the adolescent (see Chapter 66, Table 66-1). The physician also must recognize that many of the adolescent’s concerns may not be disclosed on the first visit and may unfold after a relationship has been established. A follow-up visit for a rather minor problem may be the visit at which other health concerns and risky behaviors are disclosed.

SCREENING HISTORY

SCREENING HISTORY

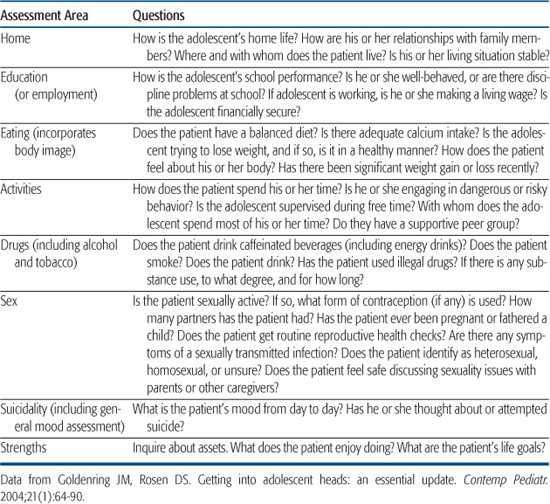

The screening history must focus on risk-taking behaviors (substance use, sexuality, recreational/motor vehicle use) and their associated risk factors, depression and its equivalents, and dietary intake.6-8 The clinician must distinguish between risk-taking behaviors that are developmentally adaptive, although often dangerous, and those that are pathologic. Using a biospychosocial model to screen enables the clinician to get a general assessment of the health and well-being of the adolescent.7 The HEEADSSS (Home, Education [or Employment], Eating, Activities, Drugs, Sex, Suicidality, Strengths) assessment tool is based on the biopsychosocial model (see Table 67-1).9 This screening allows clinicians to assess the patient’s well-being in a variety of domains. Over the past decade, there has been an increased emphasis on strength-based care, which encourages clinicians to ask about assets and the positive aspects of their patients’ lives. This new paradigm is embedded in the last S of the HEEADSSS assessment.10

In addition to a detailed history, adolescents should have a comprehensive physical examination annually. Developmental progression, including assessment of Tanner and Marshall sexual maturity rating (SMR), should be noted.

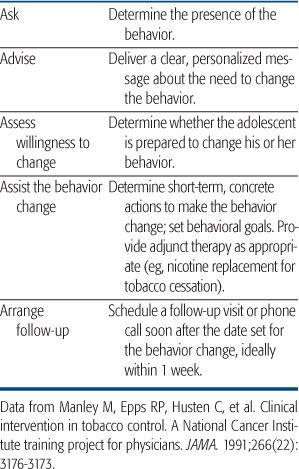

Behaviors that reflect possible involvement in risk behaviors include problems in family and peer relationships, a decrement in school functioning, legal problems, and behavioral problems reflective of substance use, including unusual or dramatic mood swings, changes in personal habits, runaway behavior, depressive symptoms, and preoccupation with generating money. Because many youths engage in risk behaviors, the clinician needs to have a brief office intervention for those engaging in such behaviors.8,11 One popular intervention based on the transtheoretical model developed by the National Cancer Institute is the 5 A’s approach12: asking, advising, assessing the willingness to change, assisting in behavior change, and arranging for follow-up (see Table 67-2). In addition to asking about risk behaviors, the clinician should query the adolescent about general mood and dietary behaviors. A 24-hour recall of dietary intake for a weekday and weekend day provides a general assessment of nutrient and caloric intake.

Table 67-1. HEEADSSS Assessment for Psychosocial Concerns: Screening History

MEDICAL HISTORY

MEDICAL HISTORY

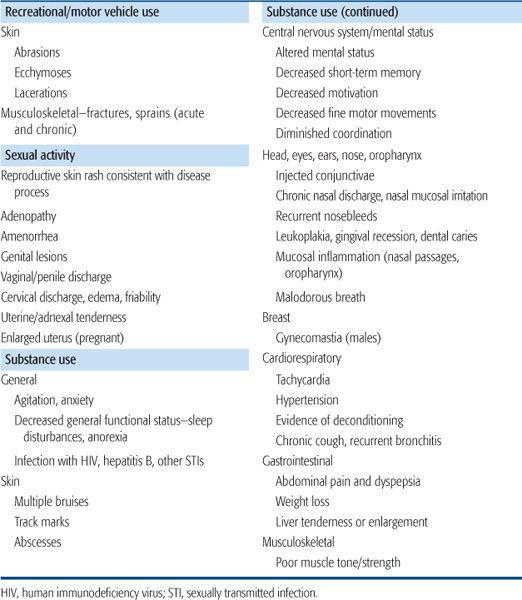

The critical components of the medical history include the current concern or presenting complaint of the adolescent and family and determination of risk for engaging in health-damaging behaviors through querying about the index or specific behavior and then other related problem activities or risky behaviors. For example, the female adolescent who is smoking cigarettes should be queried about sexual activity. Confining the evaluation to the most obvious behavior (eg, cigarette smoking) and ignoring the other highly related behavior might place the adolescent at risk for a more immediate negative outcome. After identification of the behavior that the adolescent is participating in, the clinician should evaluate the extent of the involvement and the impact on the health of the adolescent. The most common physical signs associated with risk behaviors on examination are outlined in Table 67-3. In adolescence, the behavioral consequences of risk behaviors often have a greater impact than the physical consequences. The components of the psychosocial inventory helpful with risk behaviors include an assessment of the intrafamily dynamics identifying major points of family support and conflict, including the parenting style of the family, and assessment of school functioning, including performance and motivation toward school, peer relationships and changes, extracurricular activities, and sexual behavior including sexual orientation.

Table 67-2. The 5 A’s for Brief Office–Based Interventions

PHYSICAL ASSESSMENT

The extent to which each organ system is evaluated depends on the complaint. In general, the physical examination of the adolescent should include all aspects of the examination of the younger child. Features related to risk behaviors (substance use, sexuality, motor/recreational vehicle use) are outlined in Table 67-3. The following section identifies areas of the general adolescent examination that differ from that for the child. Parents should be informed that the examination will include an examination of the genitalia and that boys will be taught how to conduct a self-testicular examination if the boy is Tanner and Marshall SMR 5.

General Appearance

Particular attention should be directed to body posture, eye contact, dress, affect, mood, and energy level. Changes in body mass index may indicate the onset of a chronic medical disease, an eating disorder, depression, or substance abuse.

Skin

Distribution of acne, hair, striae, ecchymoses, “needle tracks,” and scars should be noted. The pubertal changes should be correlated with the appropriate stages of sexual development, as described by Tanner and Marshall (see Chapter 63, “Somatic Growth and Development during Adolescence”). Striae are common in areas of rapid growth, especially where subcutaneous fat is increasing (hips, breasts, buttocks, and lower abdomen). Longitudinal scars on wrists may indicate suicide gestures or attempts or cutting behavior. Major scars or ecchymoses may indicate a history of unintentional injuries.

Eyes

Conjunctival injection and alterations in pupil reactivity may indicate substance use. Visual acuity commonly changes, and astigmatism can appear during adolescence. If the adolescent cannot identify more than half the letters on the 20/40 line of the Snellen chart, a referral to an ophthalmologist is indicated.

Ears

Hearing is best checked by a pure-tone audiogram in early adolescence. The most common problem is high-tone sensorineural defects that may be related to listening to highly amplified music.

Nose

Constant erythema, trauma of the nose, or epistaxis may indicate substance use by inhalation. Trauma may also lead to a deviated septum.

Teeth

Periodontal disease begins in adolescence. Malocclusion occurs in approximately 50% of adolescents. Referral for dental services is often indicated.

Table 67-3. Findings Associated with Risk Behaviors

Glands

Lymph nodes are generally palpable in the cervical, axillary, and inguinal areas. Lymph nodes greater than 1 cm and those that persist longer than 2 to 3 weeks should be investigated for infection or malignancy. Common infections associated with lymph node enlargement include infectious mononucleosis, pharyngitis, vaginitis, salpingitis, urethritis, and prostatitis. Examination of the breasts should be done for both males and females. Gynecomastia is a common finding in males beginning at Tanner and Marshall SMR 2. Gynecomastia usually does not persist beyond SMR 4. Girls should be staged for Tanner and Marshall development. Teaching self-breast examination is not critical during adolescence. Chapter 74, “Breast Masses,” discusses abnormalities found during adolescence.

Cardiovascular System

The examination of the cardiovascular system is standard. Precordial activity may be somewhat increased because of a hyperdynamic state secondary to anemia, anxiety, pregnancy, or substance use. Congenital cardiac abnormalities will usually be diagnosed before adolescence. Prolapsed mitral valve and lesions secondary to rheumatic fever may first be diagnosed during adolescence. Increases in blood pressure can result from anxiety or substance use.

Rectal Examination

Rectal examinations of the adolescent are indicated with symptomatic genitourinary and gastrointestinal complaints including a history of receptive anal coitus.

Musculoskeletal System

Examination of the spine is undertaken to exclude scoliosis (see Chapter 216). Muscle strength and joint flexibility should be checked.

Genitalia Examination

The examination of the male and female genitalia is a critical part of the examination for the adolescent patient. Boys and girls should have their genitalia inspected for normal development and Tanner and Marshall staged. The external examination of both males and females should include inspection for erythema, ulcerations, and discharge. See Chapters 76 and 233 for further discussion of assessment. Males who are uncircumcised should be assessed to see if their foreskin could be pulled back. When males are at SMR 5, they should be instructed on self-testicular examination. Scrotal and testicular masses are discussed in Chapter 75. Pelvic examinations are indicated only if the patient presents with genitourinary or gastrointestinal symptoms that require the examination to establish a diagnosis.

Mental Status

Reading ability, comprehension, writing skills, and cognitive ability should be evaluated. Marked alterations in mood and energy are not consistent with normal adolescence. If the adolescent appears to have marked mood swings, the clinician must consider psychopathology, including substance use. Higher cognitive functioning may be measured through tasks that require sequencing, memory, spatial relationships, and organizational skills.

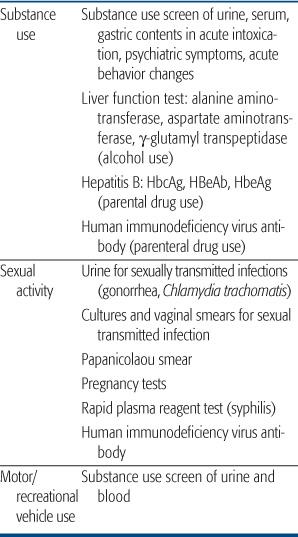

LABORATORY SCREENING

Routine laboratory screening should include tuberculin skin tests, the frequency being determined by the risk status of the population, including environmental exposure risk. Current practice includes screening every 2 years. Table 67-4 lists screening laboratory tests for specific risk behaviors. The role of substance use screening for comatose or combative youth in the emergency setting and with the onset of psychiatric symptoms is clear. There is considerable controversy regarding screening to confirm a suspicion of substance use in the routine office visit. There is little to be gained by screening adolescents who use substances unless they are engaged in a treatment program. Considerable problems exist with the sensitivity and specificity of urine screening for substance use. Testing indicates the presence or absence of use in the preceding few days and does not provide information about frequency, intensity, or chronicity of use. Ethical and legal issues must be addressed in obtaining the adolescent’s consent in a none-mergency situation. Drug testing to confirm a history also conveys a message to the patient: The clinician does not believe the history. This statement may interfere with development of a long-term therapeutic relationship with the adolescent. Screening for sexually transmitted infections is discussed in Chapter 233. Cervical cancer screening should begin within 3 years of the onset of sexual activity (see also Chapter 78).13 Screening for dyslipidemia and the associated medical problems associated with overweight and obesity are discussed in Chapter 32. These guidelines are based upon family history and body mass index percentile.14

IMMUNIZATIONS

The clinician must review the adolescent’s immunization status and consider whether the patient has completed his or her primary series of general immunizations (see Chapter 244). Because of recent outbreaks of pertussis in teenagers and adults, adolescents should receive a TdAP vaccine 5 years after their previous tetanus-diphtheria or diphtheria-tetanus-pertussis vaccination. All adolescents should receive a trivalent measles-mumps-rubella vaccine unless there is documentation of 2 measles-mumps-rubella vaccinations earlier in childhood. The vaccine should not be given to an adolescent who is pregnant. All adolescents should receive the full 3-dose vaccination against hepatitis B if not given earlier. The adolescent platform now includes vaccines for Meningococcus, Varicella, Influenza, and Hepatitis A. Human papilloma virus vaccination is recommended for females.

See the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Advisory Committee for Immunization Practices for recent updates on recommendations.15

Table 67-4. Screening Laboratory Tests for Specific Risk Behaviors

PREVENTION

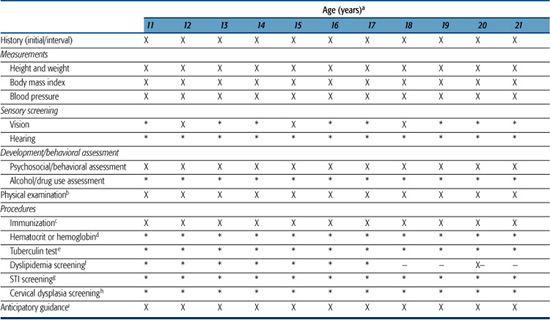

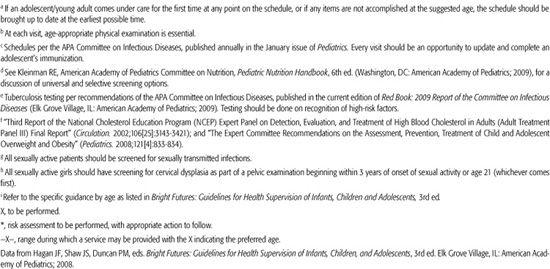

Over the past decade, a series of recommendations have been developed and modified (Guidelines for Adolescent Preventive Services, Bright Futures) for preventive services and screening during adolescence.16,17 In Table 67-5, the recommendations for adolescence and young adulthood are highlighted. Many of the recommendations focus on health-promoting and health-damaging behaviors initiated during early adolescence. Sexual behavior, substance use, and vehicle use are often initiated during adolescence and continue to account for the major causes of morbidity and mortality through the fourth decade of life. Because intention to engage in a behavior is one of the most powerful predictors of initiation of a behavior, simple questions regarding intention should be a routine part of each clinical encounter beginning in late childhood. The identification of 1 risk behavior should alert the clinician to inquire about other risk behaviors. In addition, the clinician should query every adolescent about depressive symptomatology, eating behaviors, school functioning, and family interaction.

Table 67-5. Recommendations for Adolescent Preventive Health Care

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree