Tetanus

Gary D. Overturf

Tetanus is an acute illness caused by an exotoxin produced by the vegetative form of Clostridium tetani. The tetanus bacillus is an anaerobic, gram-positive, spore-forming organism. Clostridium tetani is normally present in the intestines of horses, cattle, and other herbivora, and is found in 2% to 30% of normal human fecal flora. The highest number of colonized persons occurs in agricultural communities. The tetanus organism is a wound contaminant and does not cause tissue destruction or inflammation.

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

EPIDEMIOLOGY AND PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Tetanus in children is rare in the United States, with fewer than 20% of cases in persons less than 20 years of age. Although it has been largely eliminated from the United States neonatal tetanus causes more than 400,000 deaths annually worldwide because of the practice of applying animal excreta to the umbilical stump for hemostasis. Neonatal tetanus is the cause of 23% to 73% of neonatal deaths and 25% to 30% of deaths in the first year of life in developing countries. The increasing use of prophylaxis in the care of wounds of all kinds, and the widespread use of active immunization have greatly reduced the incidence in older children.

Contamination of wounds by spores of the tetanus bacillus occurs without clinical signs of infection. Anaerobic conditions in the wound allow conversion of spores to the vegetative form and the subsequent production of a plasmid-encoded exotoxin, tetanospasmin, that acts at the myoneural junction of skeletal muscles and on neuronal membranes in the spinal cord, to block inhibitory pulses to motor neurons, producing spasms of muscles. This requires a low oxidation-reduction potential, which is achieved in deep puncture wounds, crushing injuries, and burns. Contamination with dirt, soil, or manure provides a heavy inoculum of organisms; however, C tetani spores are ubiquitous, and any wound has the potential to become contaminated.

Although some toxin diffuses into the surrounding muscles, most toxin is distributed hematogenously to neural tissues. The toxin’s action in the central nervous system lowers the threshold of reflexes in which the lower motor neurons are involved, and induces susceptibility to reflex spasms and convulsions. The toxin combines with high affinity to neural tissue and binding is essentially irreversible by antitoxin. Thus, only toxin circulating in the blood can be neutralized by antitoxin.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

Two clinical forms of tetanus are observed: generalized and local. The two forms may occur simultaneously. In children, local tetanus is rare, presenting with stiffness in a single group of muscles, such as those of the jaw, the muscles of deglutition, or muscles in other parts of the body. The generalized form is more common, especially in the developing world.

Tetanus produces no characteristic pathologic changes in muscle. Various lesions may result from the violent spasms, such as hemorrhage in muscles, or even rupture of skeletal muscles and compression fractures of vertebral bodies.

Mean incubation period is 5 to 12 days after infection. Short incubation periods (eg, ≥ 5 days) are associated with higher mortality rates, whereas long incubation periods (eg, ≥ 10 days) are associated with the lowest mortality rates. The local wound is often unremarkable and appears to be trivial. The onset is insidious, with gradually increasing stiffness of muscles, particularly those of the neck, jaw, and the large muscles of the back and lower extremities. Within 24 hours of the onset of first symptoms, the disease is generally fully evident with marked stiffness or spasms of the jaw and neck (trismus). Swallowing may be difficult, and other parts of the body musculature progressively become involved. Certain spasms are quite characteristic of tetanus. Cutaneous, auditory, or visual stimulation and attempts at voluntary motion initiate paroxysmal contraction of the muscles of the body as a whole that lasts for 5 or 10 seconds. During the spasm, the entire body becomes rigid; the head is retracted, the back is arched in opisthotonos, the legs and feet are extended, and the arms are outstretched, with fists clenched and thumbs adducted. The jaws are immobile, and the face assumes a tonic expression known as risus sardonicus. The eyebrows are raised, the palpebral fissures narrowed, the angles of the mouth drawn downward and outward, and the upper lip is pressed firmly against the teeth. Consciousness is not lost, and the patient is usually very apprehensive.

At first, spasms are infrequent, with complete relaxation between episodes and only mild discomfort. With progression, spasms become more numerous, more prolonged, and painful. Relaxation between the seizures is then only partial, and a considerable degree of rigidity persists. The paroxysms may affect the respiratory muscles or those of the larynx, with fatal results. Partial or complete relaxation occurs during sleep or with anesthesia, and sedatives may afford some relief. Spasm of the sphincters with retention of urine is common. Sweating is sometimes marked but fever is usually absent. The duration of tetanus in fatal infections is seldom more than 3 or 4 days, and may be less than 24 hours. Death usually results from respiratory failure, and body temperature sometimes shows an abrupt terminal rise. Patients who recover seldom have much fever; after several days the paroxysms gradually decrease in frequency and the muscular rigidity diminishes, although several weeks may elapse before they disappear entirely. Trismus is often the last symptom to disappear.

Tetanus neonatorum usually follows introduction of C tetani into the umbilical cord. The illness usually starts between the third and tenth day of life and is manifested by excessive crying and unwillingness or inability to suck. These symptoms are rapidly followed by trismus, sustained tonic contractions, spasms, and convulsions.1 Anoxia, exhaustion, and caloric deprivation result in death.

DIAGNOSIS

DIAGNOSIS

Tetanus must be diagnosed clinically. The causative organism, C tetani, may not be demonstrable, but finding the organisms alone cannot confirm the diagnosis. There are few diseases with which tetanus is apt to be confused. The history of a wound, the onset with trismus, the facial expression, and the spasm accentuated by external stimuli are quite characteristic. Meningitis may be difficult to rule out without lumbar puncture. The differentiation from rabies is discussed in Chapter 321. Muscle spasms resulting from a dystonic reaction are easily confused with tetanus but its causes are likely to be elicited in the medical history.

Local tetanus should be considered when stiffness of muscles and irritability to local mechanical stimuli develop in the neighborhood of a wound, particularly a compound fracture.

Laboratory studies are rarely specific. Cerebrospinal fluid findings are normal; leukocytosis may be present. Wounds should be débrided and cultured for C tetani.

TREATMENT

TREATMENT

The management of tetanus includes careful supportive measures, control of spasms and seizures, prevention of complications, administration of antitoxin to prevent the binding of additional toxin, and surgical debridement where needed. Noise and unnecessary disturbance should be minimized to decrease the frequency of spasms. Maintenance of oxygenation is of prime importance. Some experts recommend routine intubation or tracheotomy and the use of assisted ventilation to reduce the risk of respiratory arrest, anoxia, and aspiration. Management of the airway includes suctioning of secretions accumulating in the pharynx and the tracheobronchial tree. Support of fluid, electrolyte, and caloric balance may be accomplished through an indwelling nasogastric tube or total parenteral nutrition.

Several classes of drugs have been used in the symptomatic management of this disease to control pain and to treat severe anxiety, seizures, spasms, and secretions. Diazepam (Valium), barbiturates, and meprobamate, in high doses given by continuous or intermittent intravenous (IV) administration, are useful. Most centers now manage tetanus with continuously administered neurologic blocking agents or general anesthesia with complete support of ventilation, fluids, and nutrition.

Tetanus antitoxin in sufficient quantity may prevent unbound toxin from reaching the central nervous system but does not displace bound toxin. The dose of antitoxin should be gauged by the severity of the disease, not by the size of the patient. Human tetanus immunoglobulin in doses of 3000 to 6000 U, given intramuscularly, is recommended. If equine or bovine antitoxin must be used, the dose is 50,000 to 100,000 U. Highly purified antitoxin should be used with appropriate testing for sensitivity. In mild disease, the intramuscular route is the safest. In severe disease, one third of the antitoxin may be given intravenously and the rest intramuscularly.

It is essential that injuries receive proper surgical care, but extensive operative intervention is neither necessary nor indicated. Although penicillin and other antibiotics will not neutralize tetanus toxin, the eradication of the toxin-producing organism from the wound is achieved with antibiotic treatment. Recent data indicate that treatment with metronidazole instead of penicillin G (doses of metronidazole are 30 mg/kg/day administered in four doses intravenously and given for 10 to 14 days) improves survival and decreases disease duration.2

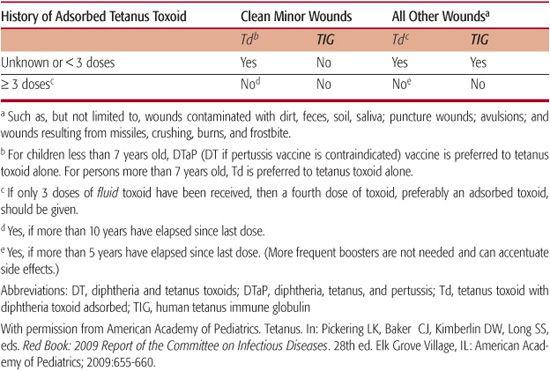

Table 289-1. Summary Guide to Tetanus Prophylaxis in Routine Wound Management

PROGNOSIS

PROGNOSIS

Age is the single most important factor in determining outcome. Most patients who survive 10 days of symptoms eventually recover completely. The disease leaves no sequelae.

Every patient with clinical tetanus should have roentgenography of the spine to detect thoracic or lumbar vertebrae compression fractures. Following recovery from clinical tetanus, the patient must be actively immunized against tetanus because tetanus disease does not induce immunity.

PREVENTION

PREVENTION

All age groups are susceptible to tetanus. Protection is afforded only by active or passive immunization. Recommendations for active immunization are summarized in Chapter 244. Following immunization, an antitoxin level of 0.01 IU/mL is considered protective.3If an individual has completed a primary series of tetanus immunization, a booster of Td (or at least one dose of Tdap when appropriate) will only be needed at the time of injury for clean, minor wounds if it has been more than 10 years since the last booster. For wounds that are dirty or neglected, or where the blood supply is severely compromised, a booster of Td (or Tdap, when appropriate) will be needed at the time of injury if it has been more than 5 years since the last booster.

Passive immunization is needed in addition to toxoid only if the primary series was never completed or if more than 10 years have elapsed since the previous booster. If passive immunization is needed, the product of choice is human tetanus immune globulin (TIG) 250 U intramuscularly. The human preparation provides longer protection and causes fewer adverse reactions than antitoxin of animal origin. The latter should be used only if TIG is not available and only after suitable sensitivity testing. The dose of TIG is 3000 to 5000 U intramuscularly. Td (or Tdap) should always be given as a booster when TIG is given to a child older than age 7 years, whereas DTaP or DT should be given at the beginning of a series to unimmunized children younger than age 7 years. If Td and TIG are given concurrently, separate syringes and sites should be used and only adsorbed toxoid is recommended in this situation.

Wound cleansing and debridement is an additional essential step in preventing tetanus. Recommendations for tetanus prophylaxis in routine wound management are shown in Table 289-1.4

REFERENCES

See references on DVD.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree