Fig. 63.1

a Abdominal CT scan in a newborn with a large gastric immature teratoma. Note the presence of calcifications. b Intraoperative photograph showing a large gastric teratoma. c a clinical photograph of a resected large immature gastric teratoma

Fetus in fetu and fetiform teratoma are rare forms of mature teratoma that include one or more components resembling a malformed fetus. Both forms may contain or appear to contain complete organ systems, even major body parts such as torso or limbs. Fetus in fetu differs from fetiform teratoma in having an apparent spine and bilateral symmetry .

A struma ovarii (literally, goitre of the ovary) is a rare form of mature teratoma that contains mostly thyroid tissue.

A dermoid cyst is a mature cystic teratoma containing hair (sometimes very abundant) and other structures characteristic of normal skin and other tissues derived from the ectoderm. The term is most often applied to teratoma on the skull sutures and in the ovaries of females.

Teratomas commonly are classified using the Gonzalez-Crussi grading system:

0 or mature (benign).

1 or immature, probably benign.

2 or immature, possibly malignant (cancerous).

3 or frankly malignant. If frankly malignant, the tumor is a cancer for which additional cancer staging applies.

Teratomas are also classified by their content:

A solid teratoma contains only tissues (perhaps including more complex structures).

A cystic teratoma contain only pockets of fluid or semi-fluid such as cerebrospinal fluid, sebum, or fat.

A mixed teratoma contains both solid and cystic parts.

Cystic teratomas usually are grade 0 and, conversely, grade 0 teratomas usually are cystic .

Sacrococcygeal Teratomas

Sacrococcygeal teratomas are the most common tumors in newborns, occurring in 1 per 30,000–40,000 births .

Sacrococcygeal teratomas occur more often in girls than in boys; ratios of 3:1 to 4:1 have been reported.

Sacrococcygeal teratomas may be diagnosed antenatally during routine ultrasound, fetal anomaly scan, or when the mother presents with clinical symptoms such as inappropriate dates to gestational age or polyhydramnios .

Those not diagnosed antenatally present in two patterns:

The most common pattern is in neonates, who present with a large, predominantly benign tumor protruding from the sacral area that is noted prenatally or at the time of delivery (Fig. 63.2).

Fig. 63.2

a–c Clinical photographs of newborns with large sacrococcygeal teratoma

Less commonly, the newborn may exhibit only asymmetry of the buttocks or present when aged 1 month to 4 years with a presacral tumor that may extend into the pelvis. Symptoms of bladder or bowel dysfunction may be present. The latter group is at a significantly higher risk for malignancy (Fig. 63.3) .

Fig. 63.3

A clinical photograph of a patient with sacrococcygeal teratoma. Note the deformity and asymmetry of the buttocks

15 % have associated congenital anomalies including:

Imperforated anus

Sacral bone defects

Duplication of uterus or vagina

Spina bifida

Myelomingocele

Elevated serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) and beta-human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) levels may be indicative of malignancy.

Ultrasound examination may demonstrate cystic components and extension of the tumor into the pelvis or abdomen. Ultrasound may reveal mass displacement of the bladder and rectum, with compression of the ureters resulting in hydroureter or hydronephrosis.

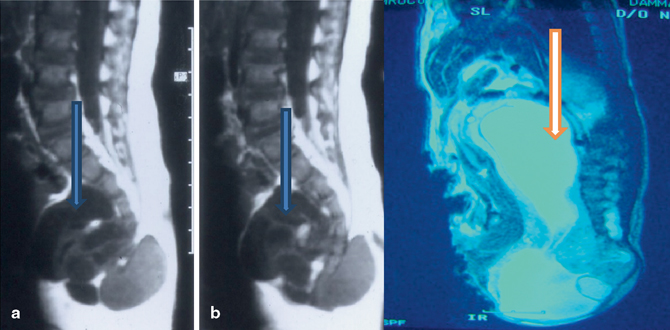

Computed tomography (CT) scanning and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the abdomen and pelvis can further delineate sacrococcygeal tumor from normal anatomic features. May detect liver metastasis and retroperitoneal lymph node involvement in malignant cases (Figs. 63.4 and 63.5) .

Fig. 63.4

a MRIs of a patient with sacrococcygeal teratoma. Note the intrapelvic extension of the tumor. b CT scan of a newborn with a very large sacrococcygeal teratoma. Note the large intra-abdominal extension of the tumor

Fig. 63.5

CT scan of the abdomen showing a large intra-abdominal extension of the tumor

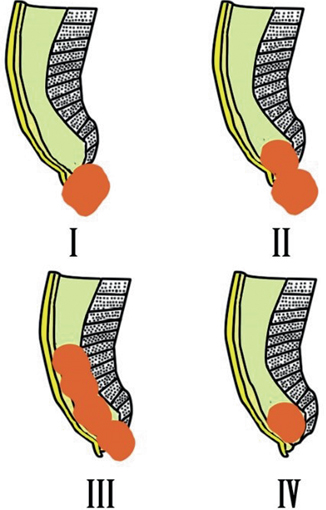

Altman’s classification (Fig. 63.6):

Fig. 63.6

Diagramatic representation of Altman’s classification of sacrococcygeal teratoma

Type I (45.8 %): Tumors are predominantly external, attached to the coccyx, and may have a small presacral component.

Type II (34 %): Tumors have both an external mass and significant presacral pelvic extension.

Type III (8.6 %): Tumors are visible externally, but the predominant mass is pelvic and intra-abdominal.

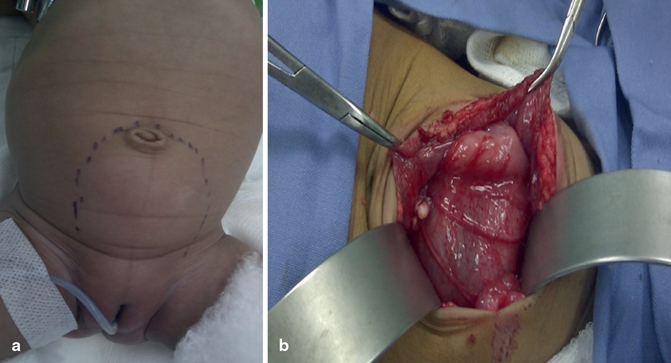

Type IV (9.6 %): Tumors are not visible externally but are entirely presacral (Fig. 63.7) .

Fig. 63.7

Clinical photograph (a) and intraoperative photograph (b) of a patient with completely intra-abdominal sacrococcygeal teratoma (type IV)

Treatment

Sacrococcygeal teratomas diagnosed prenatally should be monitored closely .

In fetuses with larger tumors, cesarean delivery should be considered to prevent dystocia or tumor rupture.

Because of the poor prognosis associated with development of hydrops prior to 30 weeks’ gestation, these fetuses may benefit from in utero surgery.

In most cases, sacrococcygeal teratomas should be resected electively in the first week of life, since long delays may be associated with a higher rate of malignancy.

Most fetal teratomas can be managed by planned delivery and postnatal surgery.

Holzgreve et al. have described an algorithm to approach the management of sacrococcygeal teratoma based on fetal lung maturity and the presence or absence of placentomegaly and/or hydrops fetalis. In the absence of placentomegaly and hydrops, the fetus should be followed by serial ultrasound until fetal pulmonary maturity is adequate for survival. The patient should then undergo elective early delivery by cesarean section to avoid trauma to the mass or dystocia .

The occurrence of placentomegaly and/or hydrops fetalis appears to be a preterminal event indicating imminent fetal demise. Its occurrence in a fetus with adequate pulmonary maturity demands emergency cesarean section. Fetuses developing placentomegaly and/or fetal hydrops prior to adequate lung maturity are the most difficult management decisions. These fetuses may be candidates for transfusion or fetal surgical intervention.

Complete excision should be done through a chevron-shaped buttock incision, with careful attention to the preservation of the muscles of the rectal sphincter.

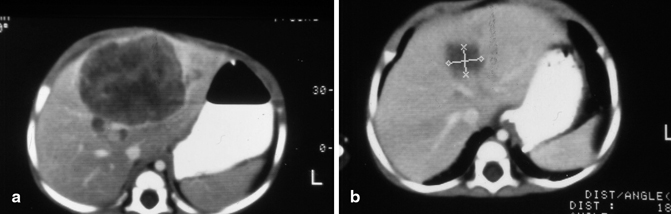

The coccyx always should be resected with the tumor, as failure to do so results in a 35–40 % recurrence rate with > 50 % being malignant (Fig. 63.8).

Fig. 63.8

Abdominal CT scan of a patient with malignant sacrococcygeal teratoma showing secondaries in the liver (a) and abdominal CT scan following chemotherapy (b). Note the response to chemotherapy

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree