Background

Posterior vaginal prolapse is thought to cause difficult defecation and splinting for bowel movements. However, the temporal relationship between difficult defecation and prolapse is unknown. Does posterior vaginal prolapse lead to the development of defecation symptoms? Conversely, does difficult defecation lead to posterior prolapse? This prospective longitudinal study offered an opportunity to study these unanswered questions.

Objective

We sought to investigate the following questions: (1) Are symptoms of difficult defecation more likely to develop (and less likely to resolve) among women with posterior vaginal prolapse? (2) Is posterior vaginal prolapse more likely to develop among women who complain of difficult defecation?

Study Design

In this longitudinal study, parous women were assessed annually for defecatory symptoms (Epidemiology of Prolapse and Incontinence Questionnaire) and pelvic organ support (POP-Q examination). The unit of analysis for this study was a visit-pair (2 sequential visits from any participant). We created logistic regression models for symptom onset among those women who were symptom-free at the index visit and for symptom resolution among those women who had symptoms at the index visit. To investigate the change in posterior vaginal support (assessed at point Bp) as a function of symptom status, we created a standard regression model that controlled for Bp at the index visit for each visit-pair.

Results

We derived 3888 visit-pairs from 1223 women (each completed 2–7 annual visits). At the index visit, 1143 women (29%) reported difficulty with bowel movements, and 643 women (17%) reported splinting for bowel movements. Posterior vaginal prolapse (Bp≥0) was observed among 80 women (2%). Among those women without symptoms, posterior vaginal prolapse did not significantly increase the odds that defecatory symptoms would develop (difficult bowel movements, P =.378; splinting, P =.765). In contrast, among those with defecatory symptoms, posterior vaginal prolapse reduced the probability of symptom resolution (difficult bowel movements, P <.001; splinting, P =.162). The mean rate of change in posterior wall support was +0.13 cm. Among women without posterior vaginal prolapse, the presence of defecatory symptoms at the index visit did not have an effect on changes in Bp over time; however, among those with posterior vaginal prolapse (Bp≥0), defecatory symptoms were associated with more rapid worsening of posterior support (difficulty with bowel movements, P =.005; splinting, P =.057).

Conclusion

Posterior vaginal prolapse did not increase the odds that new defecatory symptoms would develop among asymptomatic women but did increase the probability that defecatory symptoms would persist over time. Furthermore, among those women with established posterior vaginal prolapse, defecatory symptoms were associated with more rapid worsening of posterior vaginal wall descent.

Posterior vaginal prolapse is thought to cause difficult defecation and splinting for bowel movements. Anatomically, it is plausible that weakness of the rectovaginal septum could interfere with the ease of evacuation of a bowel movement. Indeed, 21–38% of women with posterior vaginal wall prolapse complain of difficult defecation or the need to splint to expel a bowel movement. Additionally, bowel symptoms (including splinting, straining, incomplete evacuation, and obstructive defecation) improve after rectocele repair.

However, cross-sectional studies show only a weak association between posterior vaginal prolapse and defecation symptoms. Other studies have failed to show any association between symptoms and stage of posterior wall prolapse. These observations appear to contradict the logic behind attributing difficult defecation to posterior vaginal prolapse. Thus, longitudinal follow up of women with and without defecatory complaints could provide valuable insights regarding a possible causal association between posterior vaginal prolapse and defecatory difficulties (as well as the converse).

In this research, we used data from a longitudinal cohort study of parous women to assess the temporal relationship between defecation symptoms and posterior vaginal prolapse. In the Mothers’ Outcomes after Delivery study, women were assessed annually for pelvic organ support and for pelvic floor symptoms. Data from this study therefore allowed us to describe changes over time in defecatory symptoms and posterior vaginal support. Specifically, we investigated 2 hypotheses: (1) symptoms of difficult defecation are more likely to develop (and to less likely to resolve) among those women with posterior vaginal prolapse and (2) posterior vaginal prolapse is more likely to develop in those women with symptoms of difficult defecation.

Materials and Methods

The Mothers’ Outcome After Delivery study was a longitudinal cohort study of parous women. This study received Institutional Review Board approval, and all participants provided written informed consent. Participants for this study were selected for recruitment based on delivery type (cesarean before labor, cesarean during labor, vaginal birth) and age at delivery. Women were recruited for participation in this study 5–10 years after the first delivery. After enrollment and informed consent, participants were followed prospectively and assessed annually for pelvic floor symptoms and prolapse. Data for this analysis were obtained from annual visits from 2008–2015.

The annual assessment for each participant included completion of the Epidemiology of Prolapse and Incontinence Questionnaire. Relevant items on the questionnaire included “Do you ever have difficulty having a bowel movement?” and “Do you ever have to push on your vagina or around your rectum to have or complete a bowel movement?” The questionnaire was self-administered each year. Posterior prolapse was assessed annually with the pelvic organ prolapse quantification (POP-Q) examination. Examiners were blinded to the symptoms, to the delivery group, and to the results of previous examinations. To capture the extent of posterior vaginal support, analysis focused on measurement at Bp. Posterior vaginal prolapse was defined as Bp≥0.

Because the goal of this study was to assess changes over time, we excluded women who attended only 1 study visit. Among those women with at least 2 visits, time-in-study varied because (1) women were enrolled in the study over several years and (b) some women dropped out of the study as the years passed. At the time of this analysis, women had participated for 2–7 years. The unit of analysis for this study was a visit-pair approximately 1 year apart (2 sequential visits from any participant, at time “T” [index visit] and time “T+1” [index visit plus 1 year]). This approach allowed us to investigate the impact of time-varying exposures and to relate them to the outcome 1 year later. For example, this allowed us to consider the impact of posterior wall support (a time-varying exposure) at time “T” on the onset of defecatory symptoms at time “T+1.” In turn, the approach also allowed us to determine whether, in women with same Bp, symptom status at the index visit was associated with a change in Bp to be different 1 year later at “T+1” (ie, effect of defecatory symptoms on Bp change). In this analysis, women who reported interval intervention (including surgery for prolapse and/or incontinence and supervised pelvic floor muscle training) were excluded because their status at follow up would presumably reflect the impact of intervention.

Our first hypothesis was that symptoms of difficult defecation would be more likely to develop and less likely to resolve among those with posterior vaginal prolapse. Thus, the first question we addressed was whether the probabilities of defecatory symptoms at visit “T+1” differs between those with or without posterior vaginal prolapse at time “T.” In this analysis, we considered separately women without defecatory symptoms at time “T” (in which case the question was whether posterior vaginal prolapse is associated with symptom onset) and those women with defecatory symptoms at time “T” (in which case the question was whether posterior vaginal prolapse is associated with symptom resolution). We used separate logistic regression models for the 2 outcomes of interest: onset of symptoms among those women who were symptom-free at the index visit and resolution of symptoms among those with symptoms at the index visit. This approach was used to generate regression coefficients the antilogs of which represent the odds ratios that quantify the association between posterior vaginal prolapse at the index visit and the outcome of interest at the subsequent visit.

The second question was whether changes in posterior vaginal support (at Bp) differed for those with or without defecation symptoms. This question was addressed with a standard linear regression model, whereby the dependent variable was the measurement of Bp at the visit “T+1”; the 2 independent variables included (1) Bp at visit “T” and (2) an indicator of whether a defecation symptom of interest was present at that visit. Thus, the regression coefficient that corresponded to the indicator for each defecation symptom quantified the expected change in Bp that can be attributed to the defecation symptom, when controlled for Bp at the index visit. To determine whether defecatory symptoms may have a different effect on posterior support among women with established posterior vaginal prolapse (ie, among those with Bp≥0 at the index visit), we included in the model a term for such interaction (ie, [Bp≥0]×[defecation symptom]).

Because women were able to contribute multiple visit-pairs to the analysis, generalized estimating equations were used to account for repeated measurements (eg, within participants).

Results

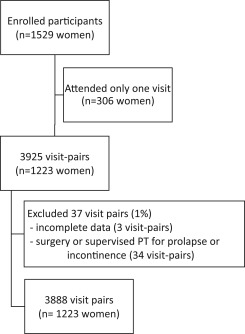

Of 1529 women, 306 came for only 1 visit and therefore were excluded from this analysis ( Figure ). The remaining 1223 women contributed 3925 visit-pairs. After excluding 3 visit-pairs (0.1%) for incomplete data and an additional 34 visit-pairs (0.9%) because of interval treatment for incontinence or prolapse, data for this analysis were derived from 3888 visit-pairs among 1223 women (each completing 2–7 visits). These pairs of visits were, on average, 1.04 years apart (interquartile range, 0.97–1.15 years). The study population is described in Table 1 . The data for those women who were excluded from the analysis (n=306) were similar to those women whose data were included.

| Variable | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| Excluded (n=306) | Included (n=1223) | |

| Age, y a | 37 (33–41) | 38 (35–42) |

| Race, % (n) | ||

| White | 76 (229) | 81 (986) |

| African American | 19 (56) | 15 (178) |

| Other | 6 (17) | 5 (57) |

| Body mass index, kg/m 2 a | 26.9 (23.4–32.2) | 25.4 (22.5–29.8) |

| Parity, % (n) | ||

| 1 | 31 (95) | 28 (341) |

| 2 | 53 (161) | 56 (690) |

| >2 | 16 (49) | 16 (192) |

| At least 1 vaginal birth, % (n) | 46 (141) | 50 (608) |

| Years from 1st delivery a | 6.4 (5.6–8.0) | 6.4 (5.6–8.2) |

| Difficulty with bowel movement, % (n) | 30 (93) | 34 (410) |

| Splinting for bowel movement, % (n) | 17 (51) | 18 (223) |

| Bp a | –2.5 (–3.0 to –2.0) b | –2.5 (–3.0 to –2.0) |

| Bp ≥0, % (n) | <1 (2) | 2 (19) |

| Interval laxative use (between times “T” and “T+1”), % (n) | N/A | 2 (19) |

| Interval childbirth (between times “T” and “T+1”), % (n) | N/A | 3 (37) |

a Data are given as median (interquartile range)

b Among 34 visit-pairs that were excluded for interval treatment of prolapse or incontinence, median Bp at the index visit was –2.0 (interquartile range, –1.5 to –2.5).

Among 3888 visit-pairs, 1143 (29%) reported difficulty with bowel movements, and 643 (17%) reported splinting for bowel movements at visit “T”. Symptom onset and resolution are shown in Table 2 . Specifically, among 2745 women who did not report difficulty with bowel movements at the index visit, 331 women (12%) reported onset of that symptom at the subsequent visit; among 3245 women who did not report splinting for bowel movements at the index visit, 179 women (6%) reported onset of the symptom at the next visit. In turn, symptom resolution occurred in approximately one-third of women who reported either symptom at the index visit, as shown at the bottom of Table 2 .

| Symptoms | At follow-up visit, n (%) | Relative odds for posterior prolapse vs none | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Onset: absent at index visit | |||

| Difficulty with bowel movements (n=2745) | 331 (12%) | 1.39 | .378 |

| Splinting for bowel movements (n=3245) | 179 (6%) | 0.82 | .765 |

| Resolution: present at index visit | |||

| Difficulty with bowel movements (n=1143) | 386 (34%) | 0.26 | <.001 |

| Splinting for bowel movements (n=643) | 206 (32%) | 0.58 | .162 |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree