Syphilis remains the most common congenital infection worldwide and has tremendous consequences for the mother and her developing fetus if left untreated. Recently, there has been an increase in the number of congenital syphilis cases in the United States. Thus, recognition and appropriate treatment of reproductive-age women must be a priority. Testing should be performed at initiation of prenatal care and twice during the third trimester in high-risk patients. There are 2 diagnostic algorithms available and physicians should be aware of which algorithm is utilized by their testing laboratory. Women testing positive for syphilis should undergo a history and physical exam as well as testing for other sexually transmitted infections, including HIV. Serofast syphilis can occur in patients with previous adequate treatment but persistent low nontreponemal titers (<1:8). Syphilis can infect the fetus in all stages of the disease regardless of trimester and can sometimes be detected with ultrasound >20 weeks. The most common findings include hepatomegaly and placentomegaly, but also elevated peak systolic velocity in the middle cerebral artery (indicative of fetal anemia), ascites, and hydrops fetalis. Pregnancies with ultrasound abnormalities are at higher risk of compromise during syphilotherapy as well as fetal treatment failure. Thus, we recommend a pretreatment ultrasound in viable pregnancies when feasible. The only recommended treatment during pregnancy is benzathine penicillin G and it should be administered according to maternal stage of infection per Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines. Women with a penicillin allergy should be desensitized and then treated with penicillin appropriate for their stage of syphilis. The Jarisch-Herxheimer reaction occurs in up to 44% of gravidas and can cause contractions, fetal heart rate abnormalities, and even stillbirth in the most severely affected pregnancies. We recommend all viable pregnancies receive the first dose of benzathine penicillin G in a labor and delivery department under continuous fetal monitoring for at least 24 hours. Thereafter, the remaining benzathine penicillin G doses can be given in an outpatient setting. The rate of maternal titer decline is not tied to pregnancy outcomes. Therefore, after adequate syphilotherapy, maternal titers should be checked monthly to ensure they are not increasing four-fold, as this may indicate reinfection or treatment failure.

Introduction

Syphilis is an ancient infection that has plagued populations for centuries. Penicillin revolutionized the treatment of syphilis and drastically decreased the rates of syphilis across all stages of disease. Yet, despite an available cure for >70 years, it remains a significant global health concern. On Nov. 13, 2015, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported a 38% increase in the rate of congenital syphilis (CS) cases in the United States from 2012 through 2014. This coincided with a 22% national increase in rates of primary and secondary syphilis in women during the same period. Reasons for the rise in rates are not entirely clear, but demonstrate the immediate need for obstetricians and gynecologists to recognize, diagnose, and treat syphilis. The purpose of this document is to review the presentation, diagnosis, and management of syphilis during pregnancy.

Epidemiology

Syphilis is caused by Treponema pallidum , a highly motile, spiral-shaped, Gram-negative bacterium, and is the most common congenital infection worldwide. The economic and reproductive costs are enormous, as 25% of pregnancies may result in stillbirth, miscarriage, or other adverse pregnancy outcomes. However, CS is largely a preventable disease, requiring safe sex practices, recognition, testing, and timely treatment during pregnancy.

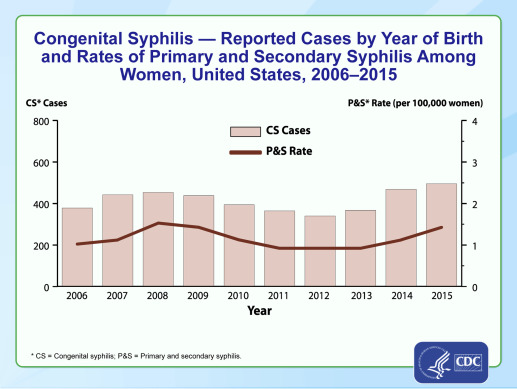

In 2007, the World Health Organization launched an initiative to eliminate CS by 2015 with goals to test 95% of gravidas for syphilis and treat 95% of seropositive gravidas. While countries such as Cuba, Thailand, Armenia, Belarus, and the Republic of Moldova have achieved elimination, rates of CS in the United States have only increased . In fact, the highest rates of CS since 2001 were reported in 2014, with a total of 458 cases of CS and a rate of 11.6 cases per 100,000 live births. This rise represented a 38% increase in CS cases during 2013 through 2014, which mirrored the 23% increase in primary or secondary syphilis rates in women during the same period ( Figure 1 ).

Substantial racial disparities are noted in syphilis cases during pregnancy. African American women represent the most highly affected demographic. Likewise, half of CS cases in 2014 were found in infants born to African American women (38.2/100,000 live births, 10 times the rate in whites), and they continue to have the highest rate of rise in incidence of primary and secondary syphilis among women.

Geographically, rates of CS have increased across all regions with the most substantial increases seen in the Northeast (74%) and West (64%). Despite a modest increase of 9% in the South, this region continues to have the highest disease burden in the United States.

Reasons for the rise in CS cases are not clear but likely multifactorial. According to data from the CDC, 21.8% of the 458 women who gave birth to infants with CS in 2014 received no prenatal care. Of the women who did receive prenatal care, 43% did not receive prenatal treatment and 17% were treated <30 days prior to delivery. Of women not treated despite receiving prenatal care, 15.6% were never tested, and 38.5% seroconverted during pregnancy. These findings highlight some of the major barriers to reducing the rates of CS, including access to prenatal care, lack of screening or diagnosis during pregnancy, and failure to provide adequate treatment.

Epidemiology

Syphilis is caused by Treponema pallidum , a highly motile, spiral-shaped, Gram-negative bacterium, and is the most common congenital infection worldwide. The economic and reproductive costs are enormous, as 25% of pregnancies may result in stillbirth, miscarriage, or other adverse pregnancy outcomes. However, CS is largely a preventable disease, requiring safe sex practices, recognition, testing, and timely treatment during pregnancy.

In 2007, the World Health Organization launched an initiative to eliminate CS by 2015 with goals to test 95% of gravidas for syphilis and treat 95% of seropositive gravidas. While countries such as Cuba, Thailand, Armenia, Belarus, and the Republic of Moldova have achieved elimination, rates of CS in the United States have only increased . In fact, the highest rates of CS since 2001 were reported in 2014, with a total of 458 cases of CS and a rate of 11.6 cases per 100,000 live births. This rise represented a 38% increase in CS cases during 2013 through 2014, which mirrored the 23% increase in primary or secondary syphilis rates in women during the same period ( Figure 1 ).

Substantial racial disparities are noted in syphilis cases during pregnancy. African American women represent the most highly affected demographic. Likewise, half of CS cases in 2014 were found in infants born to African American women (38.2/100,000 live births, 10 times the rate in whites), and they continue to have the highest rate of rise in incidence of primary and secondary syphilis among women.

Geographically, rates of CS have increased across all regions with the most substantial increases seen in the Northeast (74%) and West (64%). Despite a modest increase of 9% in the South, this region continues to have the highest disease burden in the United States.

Reasons for the rise in CS cases are not clear but likely multifactorial. According to data from the CDC, 21.8% of the 458 women who gave birth to infants with CS in 2014 received no prenatal care. Of the women who did receive prenatal care, 43% did not receive prenatal treatment and 17% were treated <30 days prior to delivery. Of women not treated despite receiving prenatal care, 15.6% were never tested, and 38.5% seroconverted during pregnancy. These findings highlight some of the major barriers to reducing the rates of CS, including access to prenatal care, lack of screening or diagnosis during pregnancy, and failure to provide adequate treatment.

Clinical presentation and stages of syphilis

Syphilis is spread through sexual contact and the spirochete penetrates mucous membranes or abrasions in the skin to disseminate systemically before clinical disease appears. The incubation period ranges from 21 days to 6 months. A primary lesion, or painless chancre, appears at the site of inoculation. Without treatment, spontaneous resolution of the chancre will occur within 4-6 weeks on average. Regional lymphadenopathy can accompany primary disease and lasts for months after the primary lesion has healed. Lymph nodes are firm, nonsuppurative, and painless. Primary disease commonly goes unnoticed.

Secondary syphilis occurs 6-8 weeks following untreated primary disease and consists of systemic and local mucocutaneous lesions with generalized parenchymal and constitutional manifestations. These manifestations can be subtle and some patients may enter the latent phase without ever recognizing secondary lesions. Table 1 illustrates the numerous clinical symptoms of secondary syphilis. If left untreated, secondary syphilis spontaneously resolves within 1-6 months.

| Stage of syphilis | Clinical findings | Location/characterization |

|---|---|---|

| Primary syphilis | Chancre Lymphadenopathy | |

| Secondary syphilis | Rash ( Figure 2 ) Patchy alopecia Condyloma lata ( Figure 3 ) Mucous patches Generalized symptoms Parenchymal effects (less common) | Distributed widely, commonly involve palms and soles Macular, papular, papulosquamous, pustular, and nonpruritic Scalp hair or eyebrows Warm/moist intertriginous areas such as vulva, inner thighs, axillae, perineum, skin under breasts Mouth, throat, or genital areas Fever, sore throat Weight loss, malaise Anorexia, meningismus Hepatitis, gastrointestinal symptoms, nephrotic syndrome, arthritis Periostitis, optic neuritis |

| Tertiary syphilis | Granulomatous lesions Cardiovascular | Skin, mucous membranes, skeleton Typically aortic lesions |

| Neurosyphilis | CNS Ophthalmologic | Cognitive dysfunction, motor or sensory deficits, auditory symptoms, cranial nerve palsies, meningitis, stroke, tabes dorsalis (syphilitic myelopathy) Uveitis, neuroretinitis, optic neuritis, Argyll Robertson pupils |

Thereafter, the patient enters the latent phase of syphilis, characterized by the absence of clinical symptoms but positive serologic tests. Early latent syphilis is latent disease <1 year duration whereas late latent syphilis is ≥1 year after infection. Syphilis of unknown duration is latent disease with no knowledge of infection duration. With the exception of early latent syphilis, latent disease is not sexually transmitted but can be vertically transmitted. In untreated early latent syphilis, up to 25% of patients can experience a relapse of secondary symptoms, thus sexual transmission can still occur.

Tertiary syphilis can develop in up to one third of untreated patients. This includes benign granulomatous lesions of the skin, mucous membranes, skeleton, and involvement of the aorta (cardiovascular syphilis). The majority of deaths from tertiary syphilis are the result of cardiovascular involvement.

Neurosyphilis can occur in any stage of syphilis. Evaluation is based on clinical suspicion, including mental status changes in the context of positive syphilis testing. Diagnosis requires a lumbar puncture showing either a positive venereal disease research laboratory test result or elevated glucose and low protein without an alternative diagnosis. Although cerebrospinal fluid abnormalities have been documented in up to 30-40% of patients with secondary syphilis, evaluation and treatment for neurosyphilis is not recommended in the absence of neurological symptoms. All HIV-positive patients should have a thorough neurologic exam and those diagnosed with neurosyphilis should be tested for HIV.

Pregnancy does not affect the course of syphilis but syphilis can significantly affect the course of pregnancy. Maternal stages are not altered as a result of pregnancy but >50% of infants will be clinically affected in untreated early syphilis and 35% in latent disease. Adverse pregnancy outcomes are 12 times more likely in untreated pregnancies. In a recent systematic review, adverse pregnancy outcomes occurred in 76.8% of untreated pregnancies compared to 13.7% of uninfected pregnancies. Even after treatment, there remains a significantly higher risk of adverse pregnancy outcomes compared to uninfected pregnancies.

Testing

Infection with T pallidum has always posed unique diagnostic challenges. T pallidum cannot be cultivated in vitro or visualized by bright-field microscopy. Additionally, no Food and Drug Administration–cleared molecular assays for detection are available. Although direct organism detection with dark-field microscopy can provide presumptive diagnosis early in infection, dark-field microscopy is not widely available and the vast majority of syphilis cases encountered in clinical practice are asymptomatic. Given these unique challenges, syphilis diagnostics have relied on serologic tests as the mainstay of laboratory diagnosis. Serologic tests for syphilis include detection of both nontreponemal antibodies and treponemal-specific antibodies.

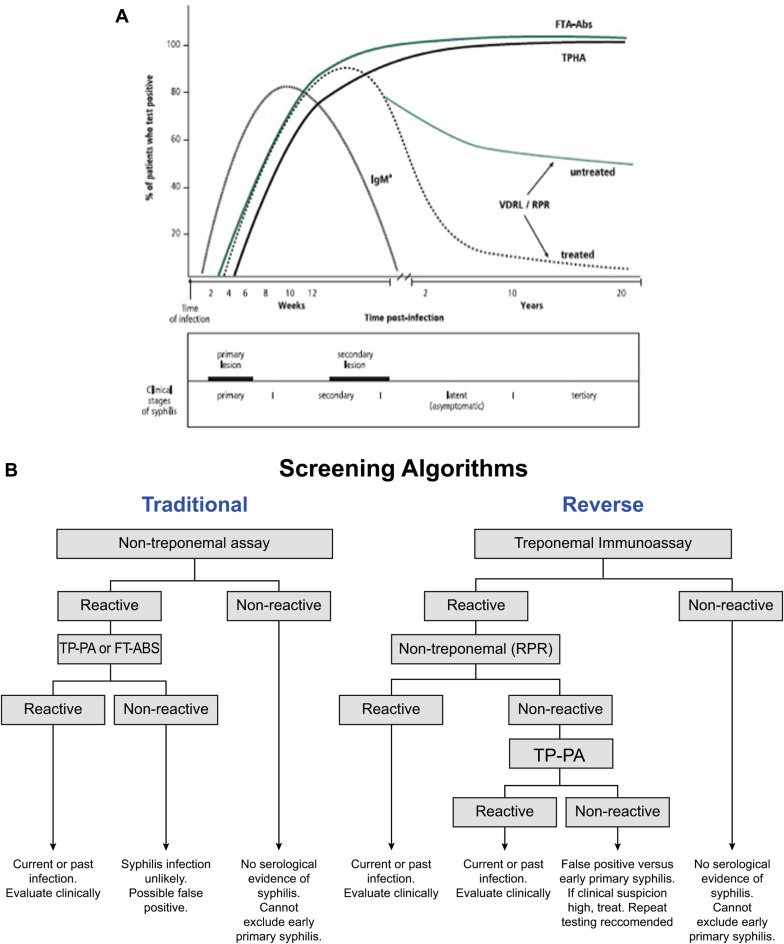

Nontreponemal tests (NTTs) include rapid plasma reagin (RPR) and the venereal disease research laboratory test, which detects both IgM and IgG antibodies against cardiolipins released from host cell damage during infection. These tests can be qualitative or quantitative with titers that increase with active disease and decrease following adequate therapy. Higher NTT titers are seen in primary and secondary syphilis as compared to latent syphilis. Most individuals convert to nonreactive following adequate treatment, although some patients will remain serofast. This is a condition of persistent low NTT titers (<1:8) without active disease and is more common with latent infection. The sensitivities of the NTTs are comparable and vary depending on stage of infection. Lower sensitivity is seen in very early and very late infection and highest sensitivity is seen in secondary syphilis. The positive and negative predictive value of the NTTs depends on the population being tested; importantly, false-positive NTT reactions have been associated with pregnancy. The US Preventive Services Task Force recently reported sensitivity, specificity, and positive and negative predictive value of each NTT and treponemal test (TT) according to stage of syphilis.

TTs include all assays that detect IgM and IgG antibodies specific to T pallidum . While these tests can confirm previous T pallidum infection, they cannot differentiate individuals who have been treated from those with an active disease. Generally, TTs remain reactive for life following eradication of the infection. Historically the most commonly used TTs were the T pallidum particle agglutination assay (TP-PA) and the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorption assay (FT-ABS). Recent advances in the detection of T pallidum antibodies have resulted in several TTs that are highly sensitive and specific and are automated to accommodate high-throughput testing. These include enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay, chemiluminescence immunoassay (CIA), and multiplex bead enzyme immunoassay (EIA) formats. The specificity of these assays are comparable to the TP-PA and FT-ABS but have better sensitivity for early primary syphilis that is sometimes missed by TP-PA, FT-ABS, and NTTs.

Due to the limitations of each available laboratory test for syphilis, no single test can be used to diagnose syphilis. As such, a diagnostic algorithm composed of multiple tests is used to diagnose syphilis. The algorithm used for decades, referred to as the “traditional algorithm,” initiates NTT screening, such as an RPR, followed by confirmation of reactive specimens with a treponemal-specific test to rule out false-positive results. In 2009 a new algorithm was proposed and designated the “reverse algorithm.” This algorithm initiates screening with a treponemal-specific test (EIA or CIA); reactive samples are tested by quantitative RPR and discrepant samples (those that test RPR nonreactive) are tested by TP-PA to aid in determination of disease and treatment status. If the TP-PA is negative (+EIA/CIA, –RPR, –TP-PA), that may reflect very early disease or false-positive EIA/CIA results. In fact, a study out of Kaiser Permanente showed that 53% of discrepant results (CIA+/–RPR/–TP-PA) during pregnancy were false positives on repeated testing (converted to –CIA/–RPR/–TP-PA). However, in high-prevalence populations or if clinical suspicion is high, discrepant results are more likely to represent early syphilis and we recommend treatment during pregnancy in lieu of repeated testing. Further, patients with possible latent syphilis but negative RPR who otherwise would be screen negative using the traditional algorithm can be detected with the reverse algorithm. Due to the risk for false-positive test results, particularly in low-risk populations, it is critical that the ordering physician understand the nature of the test being ordered. Many laboratories offer the reverse diagnostic algorithm and will reflex tests appropriately, however, if the laboratory does not automatically reflex to the appropriate confirmatory tests following a positive treponemal-specific test it is incumbent on the physician to do so. Figure 4 shows the timeline of testing components and a flow chart for both the traditional and reverse sequence algorithms.

Each of the 2 algorithms has strengths and weaknesses, and importantly laboratories establish which algorithm best suits the needs of their population. Typically, high-volume laboratories will utilize the reverse algorithm to take advantage of the high sample throughput, automation, and objective test interpretation. In low-volume settings, the traditional algorithm may be more cost-effective despite the requirement for manual operation and subjective interpretation of NTTs.

Neither testing algorithm (described later in the review) can distinguish between previously treated vs untreated syphilis. Therefore, when patients have both positive treponemal-specific and -nonspecific test results, in the absence of clinical symptoms, the differential diagnosis is serofast (previously treated syphilis with persistent low RPR titers) vs latent syphilis. Treatment history and prior RPR titers will help distinguish between the 2 diagnoses, and can often be obtained from local or state departments of public health. In the presence of previous inadequate treatment or no known treatment and unknown timing of infection, we recommend treating pregnant patients as syphilis of unknown duration.

Prevention and identification of CS depends on careful maternal screening. Syphilis testing is recommended at initiation of prenatal care in all women, but only select states have mandatory third-trimester testing and providers should be familiar with their state laws regarding frequency of testing. Selective screening based on state laws, geographic prevalence, and patient risk factors follows regulatory guidelines and CDC recommendations; however, without universal third-trimester testing, the true prevalence of syphilis will not be recognized. In women at high risk for acquiring syphilis, testing should occur at 28-32 weeks and again at delivery ( Table 2 ). In addition, all women who present with a stillbirth >20 weeks’ gestation should be tested and all patients diagnosed with syphilis should also be tested for HIV. Syphilis is a nationally notifiable condition and requirements for reporting vary by state. State laws regarding reporting requirements can be found at http://www.cdc.gov/std/program/final-std-statutesall-states-5june-2014.pdf .

| High morbidity area (rates of primary and secondary syphilis of ≥2 per 100,000) |

| No evidence of prior testing |

| Uninsured or low income |

| Diagnosed with STD during pregnancy |

| Exchange sex for money or drugs |

Multiple studies have demonstrated cost-effectiveness of syphilis screening at the initiation of prenatal care. Recently, the cost-effectiveness of repeat testing has been evaluated. These studies utilized lower rates of primary and secondary syphilis, which are not applicable to all geographic regions. The incidence of syphilis may also be underrecognized in regions that either do not perform repeat testing, or have higher rates of CS discordant from rates of primary and secondary syphilis. In addition, the model attributed a low rate of preterm delivery related to syphilis, and even lower rates of presumed CS in women with early syphilis. Contemporary studies are lacking that evaluate seroconversion rates during pregnancy, making the models highly contingent on older, less accurate data. For these reasons, we encourage repeated third-trimester testing in all women during pregnancy.

Ultrasound findings and pathophysiology of fetal syphilis

Vertical transmission of syphilis occurs in all stages of syphilis and in each trimester of pregnancy. Fetal infection occurs in >50% of untreated early syphilis and 35% of untreated latent disease. Amniocentesis and percutaneous umbilical blood sampling were previously used to document fetal infection, but comprehensive fetal ultrasound is now the most common method used to evaluate for fetal infection. Characteristic fetal abnormalities seen with ultrasound are the result of a robust inflammatory response to T pallidum and typically not seen <20 weeks as the result of fetal immunologic immaturity. Pregnancies with evidence of fetal infection by ultrasound have higher rates of fetal compromise during treatment as well as fetal treatment failures. Before 20 weeks, ultrasound abnormalities are usually not seen and treatment is uniformly successful.

Ultrasound abnormalities suggestive of fetal syphilis can be seen >20 weeks and in all stages of maternal syphilis. One study found that 31% of infected gravidas had evidence of fetal syphilis on pretreatment ultrasound. These abnormalities, in decreasing frequencies, include :

- •

hepatomegaly (80%).

- •

elevated peak systolic velocity of the middle cerebral artery (MCA) by Doppler ultrasound indicative of fetal anemia (33%).

- •

placentomegaly (27%).

- •

polyhydramnios (12%).

- •

ascites (10%) and fetal hydrops.

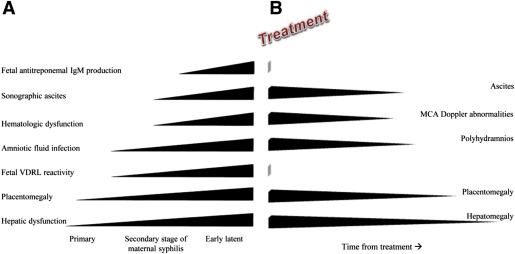

The pathophysiology of fetal syphilis was first described by Hollier et al in 2001 and completed in 2014 by Rac et al. Fetal syphilis is a continuum characterized by early hepatic and placental involvement followed by amniotic fluid infection, hematologic dysfunction, and finally ascites and fetal IgM production. As maternal stage of syphilis progresses untreated, more abnormalities develop. After adequate syphilotherapy, findings of late fetal syphilitic infection (MCA Doppler abnormalities, ascites) resolve first and findings thought to occur early, such as placentomegaly and hepatomegaly, are the last to resolve ( Figure 5 ).