22.3 Teeth and oral cavity disorders

Development

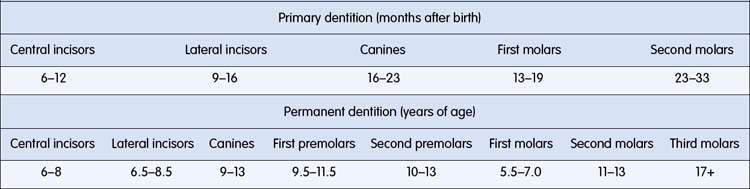

Teeth start to form from the fifth week in utero and may continue until the late teens or early twenties with the eruption of the third permanent molars (or wisdom teeth) (Table 22.3.1). The first tooth to erupt is usually a lower central incisor at around 7 months of age. By the age of 2.5 years most children will have a complete primary dentition consisting of 20 teeth: 8 incisors, 4 canines, 8 molars. At around the age of 6 years, the primary incisors become mobile and fall out. Most people have 32 permanent teeth, the first of which to erupt is usually the lower first permanent molars at around 6 years of age. The period that follows, referred to as the mixed dentition phase, is highly variable.

• Provided the sequence of eruption of the teeth is in order (central incisors before lateral incisors, etc.), delays per se are not a cause for concern.

• Asymmetrical eruption, particularly of the permanent incisors, should be reviewed by a dentist in order to check that there is no obstruction (such as an extra tooth) to the eruption of the appropriate tooth.

• The simultaneous presence of primary and permanent teeth during the mixed dentition phase is generally not a problem.

• Premature loss of primary teeth can be a sign of underlying systemic disease and should be reviewed by a paediatric dentist.

Developmental anomalies

Oral alveolar developmental cysts

Natal and neonatal teeth

• Present in 1 in 3000 births, or erupt in the neonatal period – usually in the lower incisor region.

• Most are prematurely erupted normal primary teeth, but some may be ‘supernumerary’ or extra teeth.

• Can interfere with breastfeeding (nipple trauma).

• Can cause an ulceration under the tongue in breastfed infants, called Riga–Fede disease, that often necessitates tooth removal.

• Removal is commonly indicated to alleviate parental anxiety and is simple (using topical local anaesthesia and a haemostat). Suggest checking vitamin K-dependent coagulation factors before removing teeth.

Developmental defects of enamel

• prenatal events such as maternal rubella virus or cytomegalovirus (CMV) infection, maternal syphilis and pregnancy toxaemia

• natal events such as prematurity, hypoxia and hyperbilirubinaemia

• postnatal events – measles virus infection, gastrointestinal disease and hypoparathyroidism.

Acquired disorders of the teeth

Dental caries

Dental caries (or decay) is an infectious disease caused by the presence of certain bacteria, predominantly mutans streptococci (MS), in the oral cavity. The MS metabolize sugars and starches to produce acids; this lowers the pH of the oral cavity and promotes loss of minerals from the tooth surface. Minerals in the saliva, including calcium, phosphate and fluoride, are re-deposited on the tooth surface once neutral pH is restored (normally after about 20 minutes). This process is dynamic and as long as minerals are replaced the tooth surface remains sound and intact. If, however, the drop in pH is prolonged and/or frequent, there will be a net loss of minerals leading to a weakening and eventual breakdown (cavitation) of the tooth surface. The early sign of mineral loss is characterized by pre-cavitated or ‘white spot’ lesions (Fig. 22.3.1A), usually around the necks of the teeth where the MS tend to colonize the oral biofilm (known clinically as dental plaque) on the teeth. Early identification of these pre-cavitated lesions is important because they signal the need for proactive preventive measures to encourage remineralization. If the disease does progress to cavitation, restorations (fillings and crowns) are necessary to rehabilitate function and aesthetics.

Early childhood caries (ECC – historically also referred to as nursing-bottle caries, baby-bottle decay, and many other terms) is a distinct form of dental caries affecting preschool-aged children. ECC is particularly virulent, causing massive destruction to the primary dentition in children as young as 14 months of age (Fig. 23.3.1B). At birth, MS do not inhabit the oral cavity; however, the earlier colonization occurs, the greater the risk of ECC. The most common source for transmission of MS has been shown to be the primary caregiver, usually the mother. Poor maternal oral health coupled with inappropriate feeding behaviours such as prolonged on-demand breastfeeding, particularly through the night after 18 months of age, and putting a child to sleep with a bottle, places an infant at high risk of developing ECC. Medical practitioners, paediatricians and maternal child health nurses are all in a strategically good position to identify individuals at risk of developing ECC (Table 22.3.2).

Table 22.3.2 Common risk factors for dental caries

| Risk factor | Influence |

|---|---|

| Fluoride exposure | Exposure to fluoridated water source and the regular use of fluoridated toothpaste are two key factors that reduce caries risk |

| Sugar exposure | Infant feeding habits are very important, with frequency of exposure being most relevant. High risk associated with prolonged bottle-feeding and on-demand night-time breast feeds (> 18 months of age) |

| Family oral health history | Poor parental oral health places child at risk of decay as cariogenic bacteria can be transmitted to infants from their primary caregiver (usually the mother) |

| Social and family practices | Poor, Indigenous, ethnic and migrant groups have higher levels of dental disease |

| Medical history | Medically compromised children are at greater risk of dental decay, the impact of which on their general health can be considerable. They are also less likely to receive appropriate treatment |

| Saliva flow | Children with reduced salivary flow are at significant risk of developing caries as the acids in the oral cavity cannot be diluted, buffered and cleared effectively. Examples of such children are those taking specific medications for management of asthma, those with ADHD, childhood cancer, or with certain head and neck tumours managed by radiotherapy |

ADHD, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

Prevention of dental caries

Strategies to prevent dental caries should start as soon as the first primary teeth erupt (Table 22.3.3).

Table 22.3.3 Summary of caries preventive strategies

| Factor | Strategy |

|---|---|

| Fluoride | A smear of child’s fluoridated toothpaste should be applied regularly to an infant’s teeth within 6 months of their eruption |

| Teeth should be brushed twice a day with nothing to eat or drink after the night-time brushing | |

| Parents should supervise tooth-brushing until around 8 years of age | |

| The use of additional fluoride supplements (tablets or drops) is no longer recommended due to the risk of unsupervised ingestion | |

| Diet | Reduce the frequency of intake of sweetened foods and drinks, particularly between mealtimes |

| Avoid on-demand feeding through the night-time | |

| Limit sugary snacks to meal times when salivary flow is optimal | |

| Avoid sugary snacks close to bedtime | |

| Increase water intake for hydration | |

| Dental attendance | Parents should be encouraged to take their infant to a dental professional within 6 months of the eruption of their first teeth |

| Regular monitoring by a dental professional should continue into adulthood | |

| Remineralizing products | Products containing fluoride concentrates and calcium phosphopeptides are available through dental practitioners. These promote remineralization of early carious lesions (e.g. Tooth Mousse®; GC Corporation, Itabashi-ku, Tokyo, Japan) |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree