Teen Pregnancy

Joanne E. Cox

Incidence of Teen Pregnancy

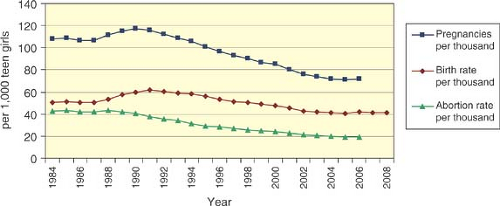

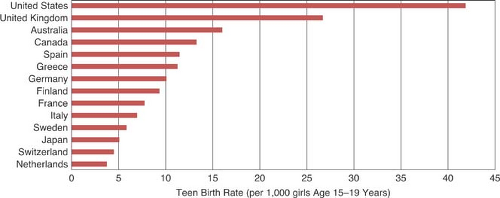

Despite a 40% decline in teen pregnancy since 1991, the United States continues to have the highest rates of teen pregnancy, birth, and abortion in the developed world (1) (Fig. 25-1). Adolescent pregnancy rates have varied 10-fold across developed countries, from a very low rate in the Netherlands (12 per 1000 women aged 15 to 19 per year), to a very high rate in the Russian Federation (100 per 1000). Japan and most western European countries have low teen pregnancy rates, <40 per 1000 (Fig. 25-2). Teen birth rates have reflected even more marked differences, ranging from 45.6 per 1000 in the Russian Federation and 41.9 per 1000 in the United States to 3.8 per 1000 in the Netherlands (2,3,4). The majority of young women in the developed world become sexually active during their teenage years. Levels of sexual activity and the age at which teenagers become sexually active do not vary much across comparable developed countries, such as Canada, Great Britain, France, Sweden, and the United States. However, analysis across these five countries shows that U.S. teens are more likely to have multiple partners and not use contraceptives at first or most recent intercourse. Cross-national studies suggest important factors for the observed differences. Strong public support and expectations for the transition to adult economic roles and for parenthood provide young people with greater incentives and means to delay childbearing. Countries with low levels of adolescent pregnancy, childbearing, and sexually transmitted infections (STIs) are characterized by societal acceptance of adolescent sexual relationships, combined with comprehensive and balanced information about sexuality and clear expectations about commitment, and prevention of pregnancy within these relationships. Easy access to contraceptives and other reproductive health services contributes to better contraceptive use and low teen pregnancy rates (5).

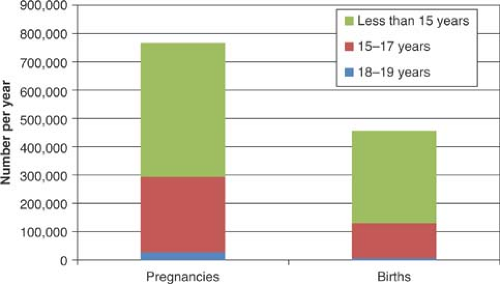

In the United States, after 15 years of continuous decline, teen birth rates for 15- to 19-year-olds increased 5% between 2005 and 2007 to 42.5 births per 1000 across 26 states from a diverse cross section of the country and then declined in 2008 to 41.5 births per 1000 and in 2009 to 39.1 births per 1000, the lowest rate recorded (3,4). Teen births were highest in the 18- to 19-year-age group (Fig. 25-3). Considerable variation remained, ranging from New Hampshire teen birth rates in 2007 of 20.0 per 1000 to Mississippi rates of 71.9 per 1000. The number of births to teenagers 15 to 19 years old rose 5% to 435,436 in 2006, compared with 414,593 in 2005, representing the largest single-year increase since 1989–1990, which was followed by another 1% rise in 2007, and a decrease in 2009 to 410,000 births (3). However, the birth rate for 15- to 17-year-olds continued to decline from 22.4 per 1000 in 2005 to 22.2 per 1000 in 2007. Conversely, the birth rate for 18- to 19-year-olds rose from 69.9 per 1000 in 2005 to 73.9 per 1000 in 2007 (6).

In 2006, 750,000 females younger than 20 years old became pregnant. For females aged 15 to 19 years, the pregnancy rate was 71.5 per 1000 in 2006, or about 7% of teens in this age group. The teenage pregnancy rate has declined 40% from a peak in 1990. There are marked state differences, ranging in 2005 from 33 per 1000 in New Hampshire to 93 per 1000 in New Mexico (6). The differences in state rankings between teen pregnancies and births most likely reflect differences in both acceptance and access to abortions. However, since 1991 there has been overall no change in teen abortion rates in the United States, suggesting that abortion has not influenced changes in teen birth rates (7).

There is a strong association between ethnicity and teen pregnancy risk (6). Currently in the United States, 53% of Hispanic teens, 50% of black teens, and 19% of white, non-Hispanic teens will become pregnant before age 20 (8). The pregnancy rate for black females aged 15 to 19 years decreased 45% between 1990 and 2005 and then increased to 126.3 per 1000 in 2006. Non-Hispanic white teens experienced a 50% decline in pregnancy and had a pregnancy rate of 44.0 per 1000 in 2006. This was in sharp contrast to Hispanic teens, whose pregnancy rate decreased 26% between 1990 and 2005, falling to 124.9 per 1000, and increased to 126.6 per 1000 in 2006 (6).

In 2007, the teen abortion rate for 15- to 19-year-olds declined from a peak in 1988 to 14.5 per 1000 (7). States with the highest teen abortion rates were New York, New Jersey, Nevada, Delaware, and Connecticut and the lowest rates were in Utah, Kentucky, Nebraska, and North Dakota, with 8 or fewer abortions per 1000 (6).

Between 1990 and 2004, U.S. repeat teen births decreased from 25% to 20% of all teen births, with 128,000 and 83,000 repeat teen births, respectively. There are considerable state variations. with repeat pregnancies making up 24% of all teen births in Texas to lows of 12% in New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont (9). Repeat births declined less for Hispanics and non-Hispanic black adolescents than for white, non-Hispanic, and Asian/Pacific Islanders.

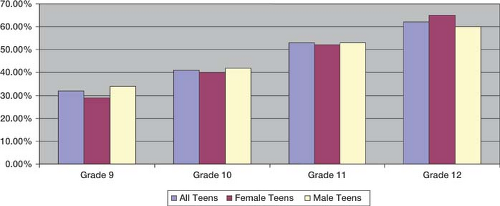

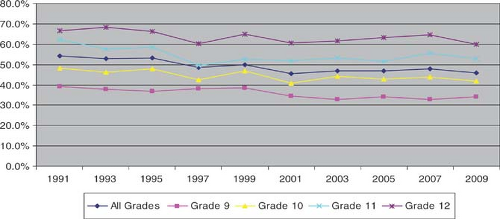

During the period 1988 to 2009, the percentage of U.S. females aged 15 to 19 years who ever had sexual intercourse decreased from 51% to 46%, while males reporting ever having had intercourse decreased from 60% to 46% (10,11) (Fig. 25-4). In 2009, high school students reporting having sex at least once varied from 34% of 9th graders to 60% of 12th graders  (Fig. 25-5). Black teens were more likely in 2009 to have had sexual intercourse than Hispanic or white, non-Hispanic teens (11). (Fig. 25-5). Black teens were more likely in 2009 to have had sexual intercourse than Hispanic or white, non-Hispanic teens (11). |

Analysis of pregnancy risk trends in adolescents in the National Youth Risk Behavior Survey from 1991 to 2009 revealed improvements in condom use between 1991 and 2003 with decreases in the youth using withdrawal and no method (10,12). Use of oral contraceptive pills declined between 1991 and 2009 among Black and Hispanic teens. In the 2009 Youth Risk Behavior Survey, of the 34.2% of currently sexually active teens, 8.9% of students reported using both condoms and birth control pills or depot medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA). Use of both

methods increased with grade in school and was highest among white students (11).

methods increased with grade in school and was highest among white students (11).

Figure 25-4. Proportion of high school students who have sex at least once, 1991–2009. (From Eaton DK, et al. Youth risk behavior surveillance—United States, 2009. MMWR Surveill Summ 2010:59[SS-5].) |

Although enormous strides have been made in teen pregnancy prevention over the last 20 years, concerns remain. Factors associated with the long-term declines in teen pregnancy include decreased levels of teen sexual activity (12,13), increased access to effective contraceptives including long-acting forms, economic prosperity, higher levels of parental education (14), and increased job and educational opportunities for all youth (15). Recent trends may represent a reversal of some of these factors. There have also been shifting racial and ethnic trends in the composition of the U.S. population, decreased access to contraceptives, and changing public perception and attitudes about teen pregnancy. The focus on abstinence-only teen pregnancy prevention since 2001 has raised concerns that teens are not acquiring the knowledge about contraceptives and have less access to reproductive health care (6,13,16,17). Less concern about HIV risk may lead to decreased use of condoms (18). Most of the increases in pregnancy rates have been in the 18- to 19-year-old age group, and most prevention efforts have not targeted this age group. Finally, within a culture saturated with sex both on television and on the Internet, an “everything goes” mentality may affect teens’ behavior and decision making.

Another factor that has affected our ability to address the problem of teen pregnancy is our acceptance of “unintended” as meaning a contraceptive failure or lack of access to or knowledge of contraception. Most teenagers report their births as unintended (19). It may be more productive clinically to explore a teen’s motivation to avoid pregnancy and ask how she intends to remain nonpregnant. This line of questioning will often expose the teen’s ambivalence about pregnancy and about contraceptive use. There may be an unconscious desire to become pregnant (19). Instead of only focusing on the logistics of contraceptives, discussion about a teen’s long-term goals, hopes, and dreams that may be incompatible with early pregnancy can be helpful (20). A strong desire to avoid pregnancy has been shown to correlate significantly with dual-method contraceptive use (21).

Table 25-1 Factors Associated with Teen Pregnancy | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Risk Factors Associated with Teen Pregnancy

In spite of the above issues, most teens do not experience early pregnancy. Multiple factors are associated with those who do engage in high-risk behaviors and become pregnant (22) (Table 25-1). They are interfamilial, sociocultural, intrapersonal, and biologic. Factors within the family include low parental monitoring (23,24,25), having a sibling who is a teenage parent (26,27,28), and a family history of teenage parenting (29). Lack of nurturing or loving parenting, high levels of mother–teen conflict, and

harsh parenting can also increase a teen’s sexual risk (29). Living in a single-parent household is also a risk factor for early sexual behavior and pregnancy, which may be due to less income and parental supervision (30).

harsh parenting can also increase a teen’s sexual risk (29). Living in a single-parent household is also a risk factor for early sexual behavior and pregnancy, which may be due to less income and parental supervision (30).

The physical and social environment contains powerful factors that shape the teen’s perceptions of the world and her hopes for the future. Surrounded by poverty and unemployment and families who have been unable to surmount it, teens often internalize a feeling of hopelessness and despair. Low family socioeconomic status is associated with early sexual intercourse (31). Poverty combined with psychological stress can markedly increase risk of early pregnancy (32,33).

Intrapersonal qualities are the filter through which teens perceive their world. A poorer sense of personal efficacy and an external locus of control are associated with early childbearing (34). Depression (35), physical and sexual abuse (36,37,38), academic underachievement, and substance use (39) have all been associated with pregnancy in adolescence.

Many teens deny their own risk of pregnancy and hold misconceptions, such as believing that only frequent sexual activity can lead to pregnancy. For some adolescents their reluctance to acknowledge their sexuality results in improper contraceptive usage. Denial of fertility is a common theme; statements such as “I didn’t think it would happen to me,” or “I had sex for 2 years and didn’t get pregnant,” or “I never thought I would get pregnant” are frequently expressed. Often the longer that adolescents are sexually active without experiencing pregnancy, the more the risk-taking behavior is reinforced. Adolescents are usually unaware that with increasing gynecologic age, the chance of regular ovulatory cycles and thus fertility is greater. They are also often unable to identify the time of greatest risk for fertility in their menstrual cycle or to understand the impact of irregular cycles on ovulation. Including a simple factual explanation of the menstrual cycle in sexuality courses in schools and office-based interventions is important.

Frequent office visits for pregnancy tests that are negative have also been labeled a risk marker for teenage pregnancy (54). Health care providers should begin addressing sexual issues early—at 10 to 12 years of age in some patients (58)—and work with parents to educate their daughters about healthy relationships, sexuality, and contraception and provide monitoring of activities.

Teen Pregnancy Prevention

Research attempting to identify effective primary pregnancy prevention among teens points to the need for a multifaceted approach and the need to begin early (58,59). Effective programs have some or all of the following components: (a) they used curriculum-based interventions that emphasize abstinence and contraceptive use; (b) they involve activities that engage teens in their communities through service-based volunteer projects in which the teens give back to others; (c) they employ youth development strategies such as academic tutoring, arts, or sports participation or help with employment; (d) they include parent programs to improve parent–child communication between target teens, mothers, and fathers; and (e) they have a broad community-wide scope that engages the broader community through educational activities, health fairs, or public service (59) (see Table 26-1).

Up-to-date resources are available at www.thenationalcampaign.org/resources/effectiveprograms.aspx. Access to confidential reproductive health care is also an essential component to teen pregnancy prevention. It is important to address these issues of confidentiality with parents and adolescents early in adolescence. Studies have shown that the presence of school-based health services is associated with local decline in teen pregnancy rates (64).

Pregnancy Diagnosis and Counseling

Pregnancy should be excluded as a cause of one or more missed periods in any adolescent who has achieved menarche. Though rare, pregnancies have been seen in teens before the appearance of their first menstrual period. Pregnancy is one of the most common cause of secondary amenorrhea. In adolescent health care, the denial of sexual activity is not reliable enough to exclude pregnancy (65). Common presenting complaints of teens with undiagnosed pregnancies are vaginal and urinary symptoms, abdominal pain, fatigue, syncope, nausea, and vomiting. A urine sample should be screened for β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-HCG). Teens who present requesting pregnancy testing may or may not be pregnant, but a valid assumption is they have initiated sexual activity and should have contraceptive counseling.

Some teens deny the possibility of pregnancy after a missed period. They are subsequently falsely reassured by light bleeding in the first trimester commonly caused by implantation of the blastocyst in the uterus or rupture of a corpus luteum cyst. Many teens make an appointment hoping the clinician will accidentally discover the pregnancy. More concerning are those teens who deliberately avoid an early diagnosis of their pregnancy because they want a baby and fear their family will insist on termination. Some express fear of physical harm.

Sensitive, confidential, and nonjudgmental options counseling is critical. Options are to terminate the pregnancy or continue the pregnancy and either place the baby for adoption or parent the baby. It is important to explore the teen’s support systems; relationships, including safety within them; plans for the future; and feelings about the pregnancy. The proportion of pregnant teens placing infants for adoption has declined sharply over recent decades, with <1% of pregnant teens choosing adoption (66). Teens choosing adoption should be referred to an agency that will provide both preadoption and postadoption counseling. There are inevitably significant issues of grief and loss when a teen relinquishes an infant. She will need some ongoing support in order to integrate the experience into her life in a healthy manner. These teens will need the services of a social worker or social service agency to ensure their safety and appropriate follow-up.

Pregnancies are dated from the first day of the last menstrual period (LMP), even though ovulation usually occurs about 2 weeks later. Assuming an accurate LMP, an estimated due date can be arrived at using the Nägele rule: to the first day of the LMP add 7 days, subtract 3 months, and add 1 year (67). Calculation of dates from the last menstrual period along with a uterine sizing is necessary to estimate gestational age and offer appropriate counseling.

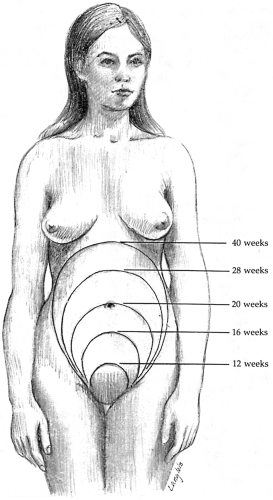

By rectal or vaginal examination the 8-week uterus feels about the size of an orange; the 12-week uterus is approximately the size of a grapefruit. An abdominal examination with the patient supine helps in staging a later pregnancy. A 12-week uterus is just palpable at the symphysis pubis; a 20-week uterus, at the level of the umbilicus; and a 16-week uterus, midway between the uterus and umbilicus (Fig. 25-6).

Pregnancy Hormone Testing

Sensitive serum pregnancy tests have made the diagnosis of early pregnancy much easier. HCG is a glycoprotein hormone secreted by the trophoblast. It is composed of an α- and a β-subunit. The β-subunit is specific to HCG (68). Radioimmunoassay using highly specific antiserum to the β-subunit of HCG can detect serum β-HCG levels as low as 2 to 7 mIU/mL. In general, results of <5 mIU/mL are considered negative.

About 7 days after fertilization, the implanted trophoblast begins to secrete β-HCG. In normal pregnancy, the β-HCG levels then rise rapidly, reaching approximately 100 mIU/mL in maternal serum by the expected date of the missed menses (69). An estimate of gestational age can be established because β-HCG levels double approximately every 2 days in the first 6 to 7 weeks of pregnancy and a gestational sac is identifiable using transvaginal sonography at β-HCG levels of 1000 to 2000 mIU/mL (70). In both ectopic gestations and spontaneous abortions, β-HCG levels are usually lower than normal and increase at less-than-normal rates during early pregnancy (see Ectopic Pregnancy, p. 482). Multiple gestations and molar pregnancies are both associated with higher-than-normal β-HCG levels (71).

Home pregnancy tests have variable accuracy. In a study of the accuracy of 18 home pregnancy tests, 100% accuracy was obtained only at β-HCG values of 100 mIU/mL (72). False-positive β-HCG tests may result from medications that contain β-HCG (infertility drugs) and high luteinizing hormone (LH) levels associated with premature ovarian failure or insufficiency. Positive results may also occur with HCG-secreting tumors. False-negative β-HCG tests usually occur with dilute urine samples, substituted urine samples (provided because of fear of drug testing), and testing too early (73). In the absence of an accurate LMP, sonographic dating may be more reliable. In the first trimester, sonographic dating is correct within 3 to 5 days. The margin of error is about 1 week in the second trimester and 2 to 3 weeks in the third trimester (69).

Because of the high prevalence of STIs in pregnant teenagers, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that tests for Neisseria gonorrhoeae and Chlamydia trachomatis should be obtained at the time of the examination (74). Routine prenatal tests include serology for syphilis, rubella, blood type and Rh factor, complete blood count, and hepatitis B surface antigen. Varicella antibody screening is indicated in the absence of a positive history of varicella immunization. Hemoglobin electrophoresis is recommended in populations at risk for sickle cell anemia and thalassemia. HIV testing is strongly recommended but not required in most states. Transmission of HIV from mother to infant can be dramatically reduced with medication (75,76,77) and operative delivery (77,78,79,80). Papanicolaou (Pap) tests are no longer recommended for patients younger than age 21 years unless immunosuppressed (81). After diagnosing a pregnancy in a teen, the clinician should provide appropriate options counseling and referral and assist the teen in keeping the appointment to the referral service. Although adolescents can be quite uncertain about the date of their last menstrual period, other diagnoses need to be entertained if the uterus is small or large for dates given. If the uterus is smaller than expected, possible diagnoses include inaccurate dates (or oligomenorrhea and irregular ovulation), lab error, incomplete or missed abortion, ectopic pregnancy, or, rarely, other sources of β-HCG (tumors). A uterus felt to be larger than expected may be caused by inaccurate dates, twin pregnancy, leiomyomata, molar pregnancy, or a corpus luteum cyst of pregnancy, which may be mistaken initially as part of the enlarged uterus. Ultrasonography and, if indicated, serial quantitative β-HCG measures are important in making the correct diagnosis. Vitamins with 1 mg of folic acid should be provided to teens if they are ambivalent or plan to continue the pregnancy to term to reduce the chances of having an infant with a neural tube defect (82). Folic acid is most effective if adequate levels are achieved prior to conception. For this reason, clinicians should

consider advising all sexually active girls to take a multivitamin with 0.4 mg of folic acid every day.

consider advising all sexually active girls to take a multivitamin with 0.4 mg of folic acid every day.

Medications/Toxins during Pregnancy

Pregnant teens should also be cautioned about drug use, alcohol intake, and smoking. They should avoid over-the-counter medications and herbal substances and should be encouraged to inform anyone who prescribes medications to them of their pregnancy. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration classifies drug classes A through D as to how much the benefits outweigh the risks to the fetus. Class X drugs have risks that outweigh benefits. Some drugs with known or suspected teratogenicity include anticonvulsants such as hydantoin and valproate sodium, anticoagulants, alcohol, folic acid antagonists (methotrexate, aminopterin), diethylstilbestrol, isotretinoin, thalidomide, alkylating agents, and lithium carbonate (83). Nausea and vomiting can be treated by avoidance of foods and supplements that trigger symptoms, changes in diet, and, if needed, low doses of vitamin B6

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree