Essentials of Diagnosis

- • Sexually transmitted disease causing a wide range of systemic manifestations.

- • Clinical disease occurs in well-characterized stages: primary (chancre), secondary (rash, swollen glands, systemic symptoms) and tertiary (dementia, neuromotor, gummatous, cardiovascular symptoms).

- • Latent periods of variable duration occur between clinical manifestations of disease.

- • Clinical disease is confirmed and latent disease diagnosed by two-stage serologic tests.

General Considerations

Syphilis is a complex disease caused by the spirochete Treponema pallidum. It occupies an interesting place in the history of disease, appearing explosively as a virulent epidemic in Europe during the age of exploration, a time of intense scientific inquiry. Although syphilis incidence has waxed and waned over the centuries since, it has never really abated. Penicillin has been and remains the therapy of choice.

Unique among the sexually transmitted diseases, syphilis is characterized by a potential to cause a wide range of systemic manifestations. It can involve nearly every organ system in a variety of ways acutely or more commonly in an insidious and chronic fashion. Latent periods between clinical manifestations may be of variable duration. It has the potential to cause serious congenital disease and appears to enhance the transmission of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

Epidemiology & Pathogenesis

Syphilis is typically acquired sexually or congenitally. Rare cases of acquisition through contaminated blood products have been reported. Syphilis can also be spread by skin or mucosal contact with an infectious lesion (eg, through nonsexual direct contact such as skin to skin or kissing). The risk of syphilis following sexual exposure to an individual with infectious syphilis is probably about 30% and is dependent on a variety of factors, including the extent and location of disease in the source patient. Long-standing immunity following infection after treatment does not occur, and repeated infections are possible.

Prevention

Most syphilis infections are sexually transmitted; therefore, measures that prevent sexual exposure, such as condom use or reduction in the number of sex partners, are effective in reducing the risk of acquiring syphilis. Syphilis is unique among the sexually transmitted diseases because of a well-characterized prolonged incubation period during which infection can be aborted by prophylactic treatment. After sexual exposure infection may be prevented with penicillin G benzathine therapy.

Preventive treatment is highly effective and a mainstay of syphilis control programs. Persons who may have been exposed to syphilis are contacted and offered preventive therapy. Those who receive timely preventive therapy will not undergo seroconversion (see later discussion of serologic testing). Waiting for serologic test results before treatment is not recommended in patients who report syphilis exposure, because the opportunity to prevent infection may be missed. All persons who report exposure should receive preventive treatment, regardless of serologic test results.

Clinical Findings

Typical of syphilis is its clinical progression through several well-characterized stages, outlined below.

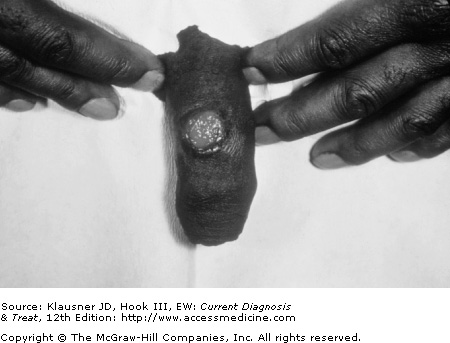

Incubation after exposure typically lasts from 1 week to 3 months. The initial manifestation is the chancre (Figure 19–1), an indurated, nontender lesion at the site of exposure. Several lesions may occur at once, but they are more often solitary. Disease is transmissible through contact with a chancre. In conjunction with the appearance of the chancre, patients usually develop nonsuppurative, nontender inguinal lymphadenopathy. Primary lesions can appear at any site of inoculation, including the perineum, vagina, cervix, anus, or rectum. Lesions can also appear on the lips or in the oropharynx.

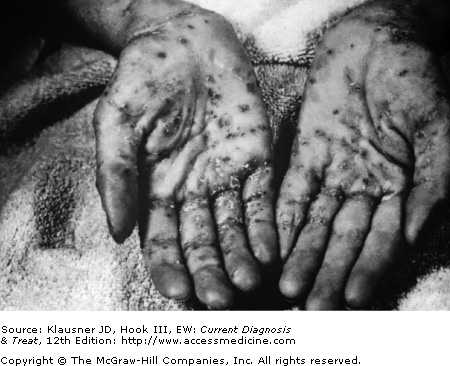

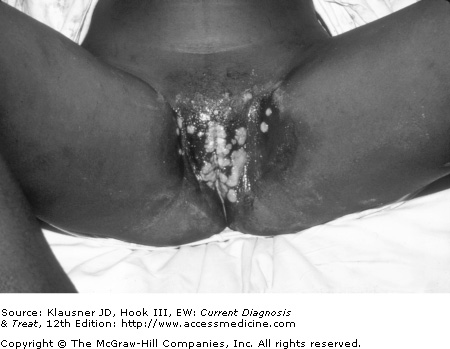

Without therapy the lesions of primary syphilis typically resolve over a period of about 3 weeks. By this time spirochetemia, first to regional lymph nodes and then systemically, has already occurred. Either coincident with the resolution of the primary lesion or more commonly several weeks later, the clinical manifestations of secondary syphilis develop. These have long been considered to be among the most diverse of all clinicopathologic phenomena. Most often they present as a diffuse maculopapular rash (Figure 19–2). Papulosquamous lesions with fine circumferential scaling may involve the palms and soles (Figure 19–3). Moist heaped-up lesions, termed condylomata lata, are seen in the intertriginous areas such as the buttocks and the upper thighs (Figure 19–4). Similar lesions, termed mucous patches, appear in the nasolabial folds and in the mouth. The moist lesions characteristic of condylomata lata and the mucous patch may transmit disease in a particularly efficient manner. Rashes covered in keratinized epithelium are less likely to transmit infection.

Patchy alopecia, diffuse lymphadenopathy, pharyngitis, or fever may also be present. Focal involvement of various organ systems, such as gastritis, uveitis, hepatitis, periostitis, meningitis, and cerebrovascular accidents, can occur as manifestations of secondary syphilis. The period of spirochetemia that is linked to the development of secondary syphilis is the most likely opportunity for transplacental transmission in the pregnant woman.

As in primary syphilis, the clinical manifestations of secondary stage disease abate with time (ie, weeks) even in the absence of specific therapy. At this point the disease is considered to have entered a latent period. Studies have demonstrated that about 25% of untreated persons with latent syphilis may have recrudescent secondary symptoms within a 4- to 5-year period after their initial resolution. The majority of these events occur within 1 year. For the sake of convention this period within 1 year of exposure is regarded as the “early latent” period. Beyond this time frame a period of long-term or “late” latency develops in which there are no clinical manifestations of infection. For most of these patients, one of three outcomes can be anticipated: spontaneous resolution of infection, persistent latent infection with some level of immunologic control, or development of tertiary syphilis after a period of years or decades. As many as one third of untreated patients with latent syphilis may go on to develop tertiary syphilis. Sexual transmission of syphilis in the latent stage is not likely.

This stage is characterized by an element of end-organ damage. There are three types of tertiary disease: neurosyphilis, cardiovascular syphilis, and gummatous (or late benign) syphilis.

T pallidum appears to have a particular predilection for the nervous system. Even in early-stage disease, invasion of the central nervous system is well documented. Although usually asymptomatic, in some instances there may be ocular manifestations such as uveitis or even cerebrovascular accidents. Central nervous system disease that manifests after long periods of latency is characterized by either vascular compromise of some portion of the neuroaxis or chronic debilitating loss of function that correlates with parenchymal destruction.

General paresis is characterized by a combination of psychiatric and neurologic findings. The letters in the word PARESIS correspond to the prominent findings associated with this aspect of disease: Personality (emotional lability), Affect (flat), Reflexes (hyperreflexivity), Eye (Argyll-Robertson pupil), Sensorium (illusions, delusions, hallucinations), Intellect (memory, judgment impairment), and Speech (slurring). The classic Argyll-Robertson pupil of late neurosyphilis is characterized by a pupil that constricts upon accommodation but not to light.

Another classic late-stage neurosyphilis syndrome is tabes dorsalis. As a result of demyelination of the posterior columns of the spinal cord, patients develop abnormalities in gait, as well as various sensory abnormalities, including characteristic “lightening” pains, bladder and bowel dysfunction, and a positive Romberg sign. The clinical presentation is usually some portion or combination of these symptoms.

A host of inflammatory ocular and otic manifestations is also attributable to neurosyphilis, as are other cranial nerve abnormalities. It is more than reasonable to consider syphilis in the differential diagnosis of nearly any psychiatric or neurologic presentation. Neurosyphilis is discussed in more detail in Chapter 20.

Unlike neurosyphilis, and probably as a result of the widespread use of systemic antibiotics with activity against T pallidum for different clinical conditions, cardiovascular syphilis is not as common today as it once was. T pallidum damages the muscular intima of the aorta and with time the resultant weakening leads to the development of an aortic aneurysm, usually of the ascending arch. Dissection, however, is uncommon. Dilation resulting from syphilitic aortitis in turn leads to aortic regurgitation. Involvement of the coronary ostia may compromise myocardial blood flow.

Gummatous disease is also extremely uncommon and is characterized by indolent destructive lesions of skin, soft tissue, and bony structures. Significant scarring may result in disfigurement. Visceral organs and the central nervous system may also be involved. Gummas may vary widely in size from small defects to large tumor-like masses. Interestingly, treponemes cannot routinely be found in tissue specimens from these lesions. The process is suspected to be largely immune mediated.

Under ordinary circumstances T pallidum cannot be cultivated in agar-based medium. Beyond clinical suspicion, diagnosis is made or confirmed through the use of darkfield microscopy, two-stage serologic tests, nucleic acid amplification tests (NAATs), direct antigen tests, or special tissue stains. The first two tests are the most commonly available. Clinicians should inform patients that reactive laboratory tests for syphilis are reportable to public health authorities.

T pallidum is too slender to be adequately observed by ordinary light microscopy and fails to take up usual stains. Instead it can be observed using darkfield techniques, which require a microscope equipped with a special condenser that angles light to allow only those rays reflected by the object of interest to enter the objective. The organism appears white against an otherwise black background, hence the term darkfield. Under such observation, the treponeme can be visualized as a corkscrew-shaped organism rotating along its long axis.

Darkfield microscopy is only useful when examining the moist lesions of primary syphilis or condylomata lata. For darkfield specimen collection, lesions must first be cleaned with saline-soaked gauze. Serous exudate is then pressed against a glass slide, which must be immediately examined before the specimen desiccates. Darkfield examination may also be used for aspirates from involved lymph nodes. The yield from resolving lesions is low.

Traditionally, a diagnosis of syphilis of any stage should be confirmed through the use of two-stage serologic tests.

Initial testing is performed with a nontreponemal serologic test. These tests use a laboratory-prepared lecithin-cholesterol antigen to detect treponemal-directed antibody in the target serum specimen. The sensitivity of these tests (which include rapid plasma reagin [RPR], Venereal Disease Research Laboratory [VDRL], and toluidine red unheated serum test [TRUST]), is very good. Specificity is slightly less reliable. A variety of factors can produce false-positive reactions, including older age, autoimmune disease, intravenous drug use, and recent vaccination.

Nontreponemal tests can be performed both quantitatively and qualitatively. Repeated tests on serially diluted specimens allow for a determination of the strength of the reaction, which roughly correlate with the extent of infection. Conversely, treatment success can be measured by demonstration of declining nontreponemal test titers over time. Because up to 20% of nontreponemal tests may be nonreactive in primary syphilis, if that is a concern either repeat testing 1 week later or testing with a treponemal specific test is indicated.

To rule out false-positive tests, when used for diagnosis, reactive nontreponemal serologic tests must be confirmed. This is done using treponemal-specific tests, which include the fluorescent treponemal antibody absorbed (FTA-ABS), T pallidum particle agglutination (TP-PA), and T pallidum

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree