Most growth arrests are seen in the adolescent population; they most commonly occur after trauma. Mizuta et al.3 collected over 2,000 bony injuries in children with open physes and found 18% of fractures had physeal involvement. In this series, growth arrest occurred just over 1% of the time and the proximal tibia was the most common site.3 The occurrence of growth arrest in adolescence does not necessarily correlate with time of injury. Bony bridges may form within 1 to 2 months after injury. However, it may take months to years before deformity or shortening due to growth arrest manifest clinically. Although there is risk stratification based on type and degree of physeal injury, it is not possible to predict which children will go on to have growth arrest. For this reason, children with a confirmed or suspected growth plate injury require surveillance for growth arrest. Early identification of a bony bridge may allow more directed and less extensive treatment. Growth arrest tends to occur more commonly in boys than in girls.4 Growth arrests are seen more commonly in the distal femur, proximal tibia, distal tibia, and distal radius.

Etiology

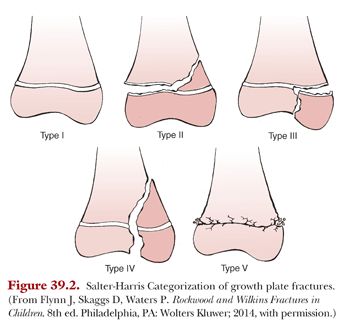

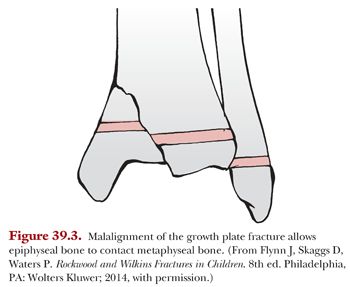

All five types of Salter-Harris fractures (Fig. 39.2) have been associated with growth arrest and development of physeal bar. Bony physeal bridges typically occur when injury to the physis results in contact between epiphyseal and metaphyseal bone. This bony contact can occur as result of displacement of fracture (Fig. 39.3) or destruction of physis from injury. Growth arrest is seen more commonly in the lower than upper extremity, although this is thought to relate to mechanism and energy of injury. Growth arrest is most common in distal femoral physeal fractures and may cause significant deformity due to the large contribution of distal femoral growth to overall limb length. High rates of shortening and angular deformity have been seen with both Salter-Harris types II and IV distal femur fractures.5 If Salter-Harris type IV fractures are not properly reduced, then the child is at particularly high risk for physeal arrest due to the risk of metaphyseal–epiphyseal contact. Epidemiologic studies have found that Salter-Harris type III fractures tend to occur near the end of growth so they do not often produce clinically significant deformity or shortening.6

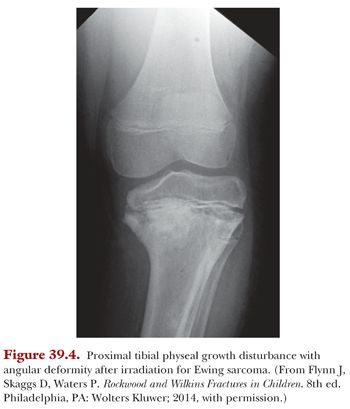

Trauma alone is not the sole cause of growth arrest in a physis nor does it have to be acute. Repetitive loading and stress-related injuries have been suggested to be causes of growth arrest.7 Bony bridges may also be caused by infections, tumors, disuse, irradiation (Fig. 39.4), thermal injuries, laser beam, metabolic disorders, vascular insufficiency, or hematologic disorders.8,9 A growth arrest may also be caused iatrogenically by violating the physis with either pins or screws. Smooth pins are thought to have minimal impact on the physis, although in an animal model, they have been associated with a small percentage of growth arrests.10 Growth arrest has been documented following anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) reconstruction in children and adolescents with transphyseal tunnel placement.11 Any type of threaded wire or screw can cause disruption of the physis and higher risk of growth arrest. Screws across the physis are sufficiently effective at growth arrest that they are commonly used when epiphysiodesis (growth plate closure) is clinically warranted.

Pathoanatomy

The various etiologies of growth arrest result in varying patterns which help guide the surgical approach to correction. Both the size as well as the location of a growth arrest influence the deformity that develops. In patients who have a complete growth arrest, the affected limb will be shortened but is less likely to develop angular deformity. Partial growth arrests will commonly lead to angular deformity of the limb, the degree of which is determined by remaining growth of the physis.

Classification

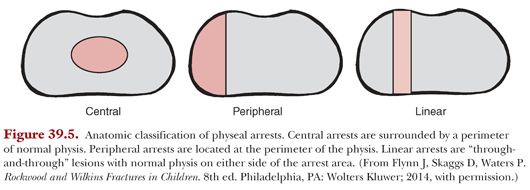

Growth arrest is classified into three separate patterns. A type I arrest is a peripheral growth arrest and a resulting peripheral bony bar. In patients with type II arrest, there is central physeal tethering due to a central arrest. In these patients, the peripheral physis continues to develop normally and the perichondrial ring is intact. Type III growth arrest is a combination of the first two; these patients demonstrate a linear bar involving the peripheral and central portions of the physeal plate (Fig. 39.5). Linear bar formation is more commonly seen after a Salter-Harris type III or IV fracture.12 These were similarly described by Peterson8 as peripheral bridge, elongated bridge, and central bridge formation.

Histopathology

Once insult has occurred to cells of physis, the resulting bony bridge consists of dense, sclerotic bone. Normal and abnormal physeal cartilage can be distinguished visually at time of surgery if physeal bar excision is indicated. The normal physis is opaque white with a bluish hue. In contrast, the injured physis has a more grayish, translucent color.13

Imaging

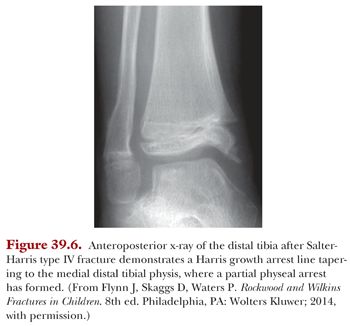

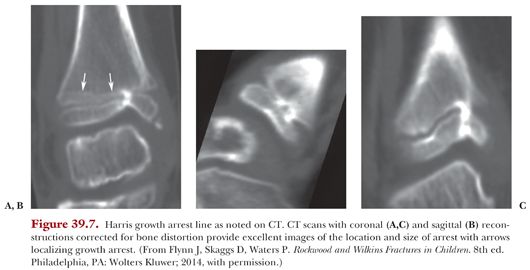

Radiographs are first obtained in order to evaluate planes of deformity. In patients with growth arrest over time, a physeal bar will be visible. Additionally, Harris growth arrest lines may be noted on the diaphyseal side of the physis and may be the first sign of bony bridge formation.14 These lines indicate slowing growth of the physis that may be due to either a localized or a systemic process. When the insult is uniform, the arrest lines are parallel to the physis. When there is a partial growth arrest, these lines will be oblique or asymmetrical in nature (Fig. 39.6). When adequate time has passed since injury, often, a distinct bridge of bone or blurred or narrowed physis will be evident. When a physeal bar from a growth arrest is noted, more advanced imaging is indicated to determine size and location in every plane (Fig. 39.7).

Bone age radiographs of the left hand may also be indicated to predict remaining growth. When attempting to correct limb length discrepancy, exact leg lengths should be determined. Computed tomography (CT) scanogram is an accurate method to determine differences in leg lengths, especially in the setting of joint contractures which may be inaccurate on standing radiographs.4 If an angular deformity is present, assessing length on both anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views of standing radiographs or low-dose biplanar radiograph (EOS) may be useful.

In order to determine the precise size and location of the bony bridge, multiplanar imaging is necessary. CT imaging can be used to determine the cross-sectional area involved by the physeal arrest. Carlson and Wenger15 described a technique on graph paper from axial images to generate a cross-sectional map from biplane polytomography. Although CT imaging is a short exam, it does involve radiation to the child, an issue of increasing concern to parents and the general population.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provides another option for the evaluation of physeal bridges. Ecklund and Jaramillo16 described use of fat-suppressed three-dimensional (3-D) spoiled gradient recalled echo imaging to assess growth disturbance. MRI has the benefit of no radiation exposure to the child compared with CT. The drawback to MRI is the longer length of the scan, which younger children may not be able to tolerate. Sedation may be required to obtain quality images. Findings on MRI include bridge size and location, signal intensity, growth recovery lines, avascular necrosis, and metaphyseal cartilage tongues.

Surgical Interventions

Surgical treatment is based on location, size, type of growth arrest, remaining growth, and anticipated deformity.12 Patient goals and activity level must also be factored into management. Treatment is necessary in patients who have or are developing significant deformity with remaining growth.17 Remaining growth for a child and ultimate limb length discrepancy can be measured in a number of ways. Commonly used techniques include the arithmetic method, the growth remaining method, the Moseley straight-line graph method, and the Paley multiplier method.18–21 Surgical treatment for growth arrest can consist of one or a combination of corrective osteotomy, completion epiphysiodesis, contralateral epiphysiodesis, limb lengthening, deformity correction with frame, or excision of the physeal bridge.

Complete Growth Arrest

In a complete physeal arrest, the most common deformity to address is limb length inequality. Decision making for approach is largely based on remaining growth. If a patient is nearing end of growth, then a complete arrest in the lower extremity may be managed nonoperatively and followed clinically. Leg length discrepancies less than 2.5 cm have been shown to have little functional deficit, although it is unclear how those deficits affect patients into adulthood. Differences of this scale are generally treated with a shoe lift or not at all. If the estimated discrepancy is greater than 2.5 cm and less than 5 cm, then epiphysiodesis of the contralateral leg may be performed. This must be made with the understanding that this will decrease the overall height of the patient. When limb length discrepancy will be greater than 5 cm, then lengthening procedures are typically indicated.

Limb length differences have different parameters for the upper extremity and are based on the long bone affected. The humerus can tolerate a significant amount of shortening without any functional or noticeable cosmetic defect. The forearm, however, does not tolerate shortening well if only one of the bones is affected. Shortening of either the radius or ulna in relation to the other can lead to problems with wrist or elbow stability.4 In Cannata’s22 series of 157 distal radius and ulna fractures, patients with less than 1 cm of length discrepancy were asymptomatic. Therefore, with significant remaining growth, shortening or lengthening of each respective bone may be indicated.

Partial Growth Arrest

For a partial growth arrest, if there is little remaining growth, one option is to surgically complete the arrest of the entire physis. Depending on the rate of growth of that physis and its contribution to overall limb length, this may be an acceptable option that avoids angular deformity of the limb. The location of the arrest will affect the resulting deformity. Peripheral bars such as a medially located bar will cause a genu varum deformity. A central arrest may lead to limb shortening and deformity of the metaphysis.4

If a growth arrest and physeal bar is small enough, it may be possible for a bar to fail with growth. Cases of spontaneous correction of partial physeal arrest have been described. Gkiokas and Brilakis23 described a case of a 3.5-year-old female who formed a bony bridge at the distal tibial physis after a Salter-Harris type IV fracture. After refusing intervention, the bridge resolved after 6 months and all deformity and shortening had been corrected.

Historically, physeal distraction had been used to disrupt physeal bars near the end of growth for small growth arrests. In this technique, tension through the bony bridge causes failure of bridge and continued growth, although it has largely been abandoned due to high complication rates.24

Bar Resection

To determine if a bar is amenable to resection, first the size and exact location of the bridge should be determined on advanced imaging. The bridge should then be mapped in relation to anatomic landmarks easily identified intraoperatively if resection is planned (Fig. 39.8). For physeal arrests that involve less than half of the physis, resection of the bar may be an alternative to epiphysiodesis. This is generally performed in patients who have significant amount of growth remaining, usually stated as at least 2 cm or 2 years of residual growth.