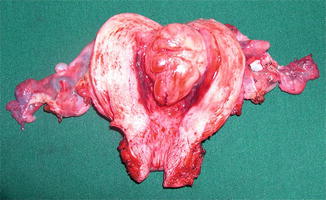

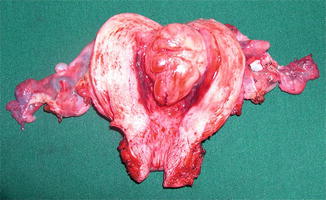

Fig. 31.1

Uterine leiomyosarcoma. Multi-lobulated grey-white tumor with areas of hemorrhage and microcysts

Simple hysterectomy with or without bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the mainstay of surgical management of uterine LMS. Ovaries can be preserved in a young patient with early-stage LMS. The risk of occult ovarian metastasis in early-stage disease is very low, reported to be less than 4 % [6–9]. Ovarian metastasis is generally associated with other extrauterine diseases [8]. A routine oophorectomy has not shown to provide survival advantage or reduce the risk of recurrence [5, 10–13]. Kapp et al. [5] in a Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) study found no difference in disease-specific survival based on oophorectomy in women younger than 50 years and stage I or II disease. Similarly, in the study by Gadducci et al. [12] that included 126 women with uterine LMS all treated surgically, there was no difference in relapse rates among stage I women younger than 50 years who had ovarian tissue preserved compared to those who had bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy (relapse rates: 23.8 % vs. 33.3; p value = not significant). On the contrary, some retrospective studies have reported an adverse impact of oophorectomy on survival. Garg et al. [14] in a SEER data base analysis of 819 women with LMS showed that on multivariate analysis performance of salpingo-oophorectomy was a poor prognostic factor (p = 0.02) along with other factors, i.e., age, tumor size, and tumor grade. In a study of 208 women of LMS from Mayo Clinic, Giuntoli et al. [11] reported that oophorectomy, high grade, and advanced stage were associated with significantly worse DSS (disease-specific survival). So the current literature suggests that grossly normal ovaries can be conserved in a young patient with early-stage LMS without any detrimental effect on survival. Likewise, when the diagnosis of LMS is made after simple hysterectomy, a re-surgery for removal of the normal adnexa is not indicated.

Another controversial issue is the role of pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy in early-stage LMS. Like soft tissue sarcomas at other sites, hematogenous spread is the primary route of metastasis for uterine LMS. Spread to retroperitoneal lymph nodes is infrequent and almost always associated with advanced disease. The risk of lymph nodal metastasis in early-stage disease is less than 3 %. Table 31.1 summarizes important studies that looked at the incidence of lymph-node metastasis in LMS [5, 7, 9, 11–13, 15–19]. Moreover, no therapeutic benefit has been reported from routine lymphadenectomy in women with early disease and clinically normal lymph nodes. Kapp et al. [5] retrospectively analyzed 1,396 women of uterine LMS; out of 348 women (24.9 %) who underwent lymphadenectomy, 23 (6.6 %) had lymph-node metastasis. All women with positive lymph nodes had advanced disease; 70 % were stage IV. The 5-year disease-specific survival was 64.2 % for women who had negative lymph nodes and 26 % with positive lymph nodes. The 5-year disease-specific survival rates were 75.8 %, 60.1 %, 44.9 %, and 28.7 % for stage I, stage II, stage III, and stage IV, respectively (P < 0.001). Lymphadenectomy did not show any impact on survival in this study. A subset analysis of early-stage disease (n = 1,079) revealed no significant difference in 3-year DSS in women who had lymphadenectomy (n = 291) compared to those who did not (n = 788) (69.7 versus 69.8 %, respectively; p = 0.90). In the Mayo Clinic study [11], lymphadenectomy was performed in 36 out of 208 women; 19 women had both pelvic and para-aortic lymph-node dissection. Four out of 36 (11 %) had positive lymph nodes. Extrauterine disease was present in three of four women with lymph-node involvement emphasizing that lymph-node involvement is generally associated with advanced disease. In another retrospective analysis of 37 women of uterine LMS who underwent lymphadenectomy, none of the women with stage I or II disease had positive nodes and all three women (8.1 %) with nodal metastases had clinically suspicious nodes [9]. Authors also suggested that even in women with gross extrauterine disease, the benefit of removing microscopically involved nodes is limited as most of these women have poor prognosis and die of distant metastasis. Therefore, the current evidence is not in favor of routine retroperitoneal lymph-node dissection in uterine LMS, and this procedure should be undertaken only if lymph nodes are grossly enlarged or in advanced disease as part of cytoreductive surgery.

Table 31.1

The incidence of lymph-node metastasis in women with uterine leiomyosarcoma

Authors (year) | Total number, N | Lymph-node dissection or sampling, N (%) | Overall lymph-node metastasis, N (%) | Early stage, N | Occult lymph node metastasis, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Major et al. [7] | 59 | 57 (96.6 %) | 2 (3.5 %) | 57 | 2 (3.5) |

Goff et al. [15] | 21 | 15 (71.42) | 4 (26.7 %) | 9 | 0 |

Gadducci et al. [12] | 126 | 7 (5.55) | 2 (29 %) | 4 | 0 |

Ayhan et al. [16] | 63 | 34 (53.9 %) | 3 (8.8 %) | 27 | 1 (3.7) |

Leitao et al. [9] | 37 | 37 (100) | 3 (8.1 %) | 27 | 0 |

Giuntoli et al. [11] | 208 | 36 (17.3) | 4 (11 %) | NR | NR |

Wu et al. [13] | 51 | 21 (41.2 %) | 0 | 12 | 0 |

Park et al. [17] | 46 | 11 (23.9 %) | 0 | NR | NR |

Kapp et al. [5] | 1,396 | 348 (24.9 %) | 23 (6.6 %) | NR | NR |

Koivisto-Korander et al. [18] | 39 | 15 (38.5 %) | 0 | NR | NR |

Hoellen et al. [19] | 14 | 5 (35.7 %) | 0 | NR | NR |

Total | 2,060 | 586 (28.4 %) | 41 (6.9 %) | 136 | 3 (2.2 %) |

Approximately 20 % of LMS women will have advanced disease at presentation. Management of these women should be individualized. Surgical cytoreduction should be considered in select cases with good performance status and in whom complete resection of tumor with acceptable morbidity seems to be feasible. The survival of women with complete tumor resection has shown to be better compared to those who had incomplete resection [20]. Lung is the most frequent site of hematogenous spread in uterine LMS. Resection of isolated or limited number of lung metastasis has shown to have a survival benefit and should be considered in appropriately selected women [21, 22].

Management of women diagnosed after surgery for benign lesion can be challenging. If the initial surgery was a myomectomy, a complete hysterectomy is recommended. However, if the initial surgery was a total hysterectomy and postoperative imaging study does not suggest residual disease, a re-surgery is not indicated. Management of women of LMS diagnosed after laparoscopic morcellation of presumed leiomyoma will be discussed later.

Endometrial Stromal Sarcoma

Endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) accounts for approximately 15–20 % of all uterine sarcomas in Western literature [23, 24]. Although endometrial stromal malignancies have been classified into low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma and undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma (UES) [25], the term “endometrial stromal sarcoma” generally refers to low-grade tumor that is typically hormone sensitive with an indolent growth and good outcome. The mean age at presentation ranges from 40 to 55 years, and many women are premenopausal at diagnosis. Abnormal vaginal bleeding is the most common presenting symptom [26]. Like uterine LMS, a preoperative diagnosis of ESS is rare, available only in less than 25 % cases [27], and many women undergo initial surgery for presumed leiomyoma or adenomyosis (Fig. 31.2).

Fig. 31.2

Low-grade ESS. On gross exam. seen as solitary, polypoidal mass projecting into the uterine cavity

A total hysterectomy is the mainstay of surgical management of low-grade ESS. Role of salpingo-oophorectomy in a young patient with early-stage disease is controversial. The risk of ovarian metastasis in early disease and with grossly normal ovaries is extremely low. Dos Santos et al. [28] reported a study of 94 cases of low-grade ESS. Out of 87 women who underwent salpingo-oophorectomy, 11 (13 %) had adnexal metastasis; all had gross adnexal tumor and disease at other pelvic extrauterine sites. Despite low risk of ovarian metastasis, conventionally bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy has been recommended as part of initial surgery because of the hormone-sensitive nature of the tumor and the potential increased risk of recurrence when ovaries were retained [29, 30]. Subsequently many authors challenged this dogma and showed that leaving ovaries in situ does not adversely affect oncological outcome in premenopausal women with early-stage, low-grade ESS [24, 31–35]. However, many recently published large retrospective studies showed adverse impact of ovarian preservation on recurrence-free survival. The study from by Bai et al. [36] included 153 women of low-grade ESS; 44 (28.8 %) had ovaries preserved at initial surgery. On multivariate analysis, ovarian preservation was found to be an independent risk factor for relapse (p = 0.0001); however, there was no impact on overall survival (p = 0.0810). In another study from Korea, Yoon et al. [37] evaluated 114 women of low-grade ESS. In this study also ovarian preservation was found to be an independent predictor for poorer recurrence-free survival (HR, 6.5; 95 % CI, 1.23–34.19; P = 0.027). Feng et al. [38] in a study of 57 women of early-stage low-grade ESS showed much higher recurrence rate with ovary-preserving primary surgery compared to those without (75 % vs. 2 %; P < 0.0001). Although the role of oophorectomy in a young patient with early-stage ESS remains controversial, the current evidence suggests that ovarian conservation increases the risk of recurrence without impacting overall survival as most recurrences can be salvaged by surgery and hormonal treatment. Therefore, ovarian preservation should be done only after appropriate counseling.

The role of routine lymphadenectomy is another controversial issue in surgical management of low-grade ESS. Table 31.2 summarizes important studies that looked at the incidence of lymph-node metastasis [15–17, 24, 28, 29, 32–34, 36, 38–43]. The overall incidence of lymph-node metastasis varies from 0 % to 37 %. The incidence of lymph-node metastasis is low in early stage (ranges from 0 % to 16 %) and is associated with other evidences of extrauterine disease or gross nodal enlargement. Many studies have reported no survival benefit from systematic lymphadenectomy in low-grade ESS [36, 38]. Therefore, a routine retroperitoneal lymph-node dissection is not recommended with apparently early-stage disease without extrauterine disease or gross lymph-node involvement. Lymphadenectomy should be considered only in cases with advanced disease or when nodes are enlarged on preoperative imaging or on intraoperative assessment. However, even in these cases, there is no consensus on the extent of lymphadenectomy, whether to debulk enlarged lymph nodes only or to do a complete pelvic and para-aortic lymphadenectomy. Other staging procedures, i.e., peritoneal biopsies, peritoneal cytology, and omentectomy, are not recommended for early-stage ESS.

Table 31.2

The incidence of lymph-node metastasis in women with uterine ESS

Authors (year) | Total women, N | Lymph-node dissection or sampling, N (%) | Overall lymph-node metastasis, N (%) | Early stage, N | Occult lymph node metastasis, N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Goff et al. [15] | 10 | 7 (70 %) | 0 (0 %) | 5 | 0 (0 %) |

Gadducci et al. [39] | 26 | 2 (7.7 %) | 0 (0 %) | 2 | 0 (0 %) |

Ayhan et al. [16] | 8 | 4(50 %) | 0 (0 %) | 2 | 0 (0 %) |

Riopel et al. [40] | 15 | 8 (53.3 %) | 3 (37 %) | 6 | 1 (16 %) |

Reich et al. [41] | 64 | 9 (14 %) | 3 (33 %) | NR | NR |

Li et al. [32] | 36 | 12 (33.3 %) | 0 (0 %) | 12 | 0 (0 %) |

Amant et al. [33] | 31 | 6 (19.3 %) | 1 (16 %) | NR | NR |

Leath et al. [42] | 72 | 23 (31.9 %) | 2 (9 %) | NR | NR |

Li et al. [29] | 37 | 1 (2.7 %) | 0 (0 %) | NR | NR |

Park et al. [17] | 37 | 17 (45.9 %) | 2 (11.8 %) | NR | NR |

Shah et al. [34] | 383 | 100 (26.1 %) | 7 (7 %) | 63 | 3 (5 %) |

Chan et al. [24] | 831 | 282 (33.9 %) | 28 (9.9 %) | NR | NR |

Signorelli et al. [43] | 64 | 19 (29.7 %) | 3 (16 %) | 16 | 1 (5 %) |

Dos Santos et al. [28] | 94 | 36 (38.3 %) | 7 (19.4 %) | 20 | 2 (10 %) |

Feng et al. [38] | 57 | 36 (63.1 %) | 0 | 36 | 0 |

Bai et al. [36] | 153 | 46 (30.1) | 1 (2.2 %) | NR | NR |

Total | 1,918 | 608 (31.7 %) | 57 (9.4 %) | 162 | 7 (4.3 %) |

Nearly 20 % women of low-grade ESS will have advanced disease at diagnosis. Although the benefit of cytoreductive surgery in these cases has not been systematically evaluated, surgery is generally recommended because of the indolent nature of the disease and the efficacy of adjuvant hormonal therapy. The extent of surgery should be individualized with the aim to achieve a complete tumor resection with minimal morbidity. Bilateral ovaries should always be removed at the time of surgery for advanced disease.

Uterus Preservation in Low-Grade ESS

Rarely, low-grade ESS may occur in a young nulliparous woman who might be keen to conserve her reproductive potential. Many cases of uterine-sparing surgery and subsequent successful pregnancies have been reported in the literature [36, 44–46]. Dong et al. [44] recently reported a case of early-stage low-grade ESS in a 25-year-old woman, treated with fertility-preserving tumor resection with uterine reconstruction followed by high-dose progesterone (medroxyprogesterone, 250 mg daily) for 1 year. Subsequently, she had spontaneous conception and delivered a healthy baby at term. Bai et al. [36] reported 19 women of low-grade ESS who underwent myomectomy. Among these, 8 women had spontaneous pregnancy.

Although uterine-sparing surgery is feasible in selected women with low-grade ESS, this approach should be considered experimental and offered only after appropriate counseling. The risk of relapse is higher with conservative surgery (Fig. 31.3). In the study by Bai et al. [36], myomectomy was found to be an independent risk factor for relapse. The recurrence rate was 78.9 % (15/19) in the myometrial resection group and 25.4 % (34/134) in the hysterectomy group (p = 0.0075), although OS was not affected (P = 0.8845) as most recurrences could be salvaged. There is also a potential risk of tumor regrowth during pregnancy due to alteration in the hormonal milieu. Koskas et al. [47] reported a case of low-grade ESS treated with conservative surgery which developed disseminated peritoneal recurrence following delivery of a healthy baby. Recently Morimoto et al. [48] reported a fatal case of ESS 10 years after fertility-sparing surgery. Therefore, myomectomy should only be offered to young women with a strong desire for fertility, after obtaining informed consent. Hysterectomy is recommended after the completion of childbearing. The long-term follow-up is mandatory as late recurrences are known in low-grade ESS. The median time of recurrence is 65 months for stage I disease [49].

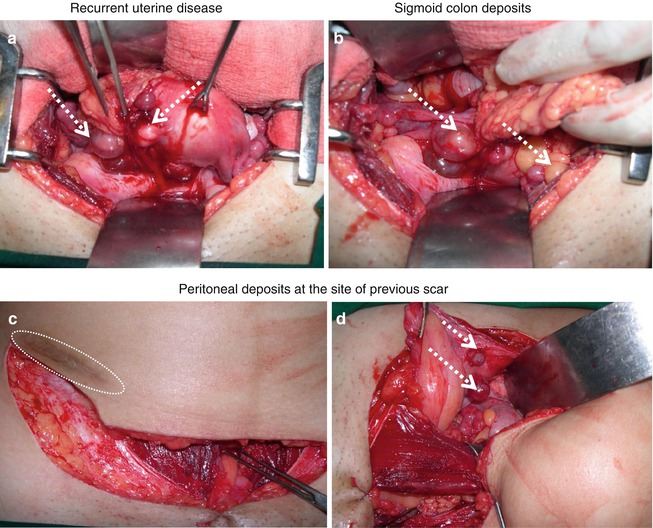

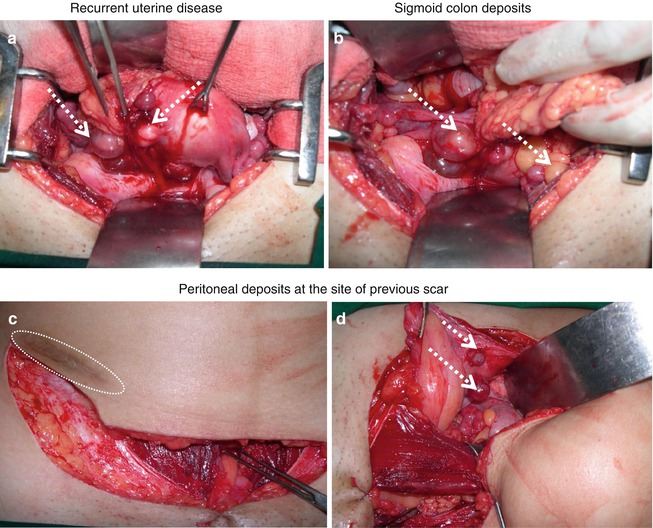

Fig. 31.3

Recurrent ESS: disease at multiple sites in a 24-year lady after initial uterine preservation surgery

Undifferentiated endometrial sarcoma (UES) is uncommon but aggressive tumor with poor prognosis. Local recurrence and distant metastasis occur early in the course of disease (within 6 months) and is associated with high mortality. Surgery is the primary treatment modality although adjuvant radiation therapy and chemotherapy are frequently used. UES do not express hormone receptors and hence do not respond to antiestrogenic treatment.

Uterine Sarcoma and Morcellation

Globally, minimal access surgery has become the standard for the surgical management of uterine leiomyoma. Intracorporeal morcellation of a large myoma for removal of the specimen is a common practice in minimal access surgery. However, one of the most dreaded complications of morcellation of presumed uterine leiomyoma is unexpected sarcoma and its inadvertent dissemination in the peritoneal cavity. In the past, it was estimated that between 1 in 500 and 1 in 1,000 surgical specimens for presumed leiomyoma would reveal leiomyosarcoma on final histopathology [50, 51]. However, a recent report from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has estimated much higher risk for occult uterine cancer in women with symptomatic fibroids who are referred for surgery, about one in 350 [52]. With dramatic increase in the use of minimal access surgery and morcellator in recent years, there is a potential threat of increase in the number of cases of uterine sarcoma undergoing inadvertent morcellation. Unfortunately, preoperative diagnosis of uterine sarcoma is rare, and majority undergo initial surgery for presumed benign lesion.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree