9.1 Surgical conditions in older children

The penis and foreskin

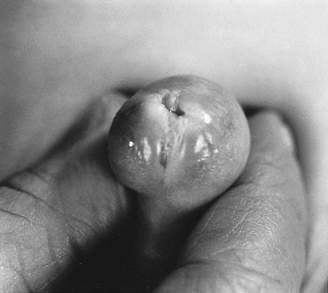

Smegma

Smegma is formed from desquamated cells and accumulates beneath the adherent foreskin. It appears as asymmetrical accumulations of yellow-tinged material, predominantly in the coronal groove beneath the foreskin (Fig. 9.1.1). There may be sufficient smegma to produce a noticeable swelling, which may be misdiagnosed as a dermoid cyst or tumour. It is often misinterpreted as being mid-shaft because a small child’s coronal groove may be a long way from the tip of the foreskin. Smegma is normal, and is released spontaneously as the foreskin separates from the glans. When it is released, it may be associated with some redness and irritation of the foreskin for a day or so; this, too, is a normal process.

Phimosis

In phimosis the opening at the tip of the foreskin has narrowed down to such a degree that the foreskin cannot be retracted (Fig. 9.1.2). The external urethral meatus is not visible. Phimosis must be distinguished from the normal adherence of the foreskin to the glans. In most boys, phimosis can be treated by topical application of steroid ointment (e.g. betamethasone valerate ointment) to the tight, shiny part of the partially retracted foreskin. This usually obviates the need for circumcision. However, marked previous inflammation, infection, skin splitting and balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO) can lead to marked scarring of the foreskin and phimosis, and in many of these children the only reasonable treatment is circumcision. Sometimes the severity of phimosis is such that there is ballooning of the foreskin on micturition, and on rare occasions it may even cause urinary retention with a distended bladder. A degree of phimosis is common in infancy but tends to resolve spontaneously in the first few years of life, and is not considered abnormal in this age group.

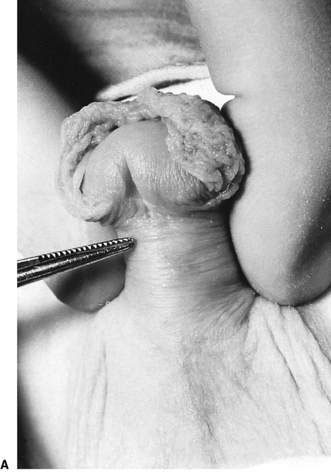

Paraphimosis

Paraphimosis occurs when a mildly phimotic foreskin has been retracted over the glans and has become stuck behind the coronal groove, causing oedema of itself and the glans (Fig. 9.1.3). It is a painful and progressive process. Treatment involves gentle manipulation of the foreskin forwards; this may require a general anaesthetic. Circumcision is not performed at this time, but a few children may need it subsequently if the phimosis does not respond to topical application of steroid ointment.

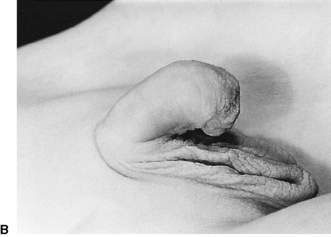

Hypospadias

It is important to recognize hypospadias when it is present (Fig. 9.1.4). The dorsal foreskin looks square and hangs off the penis, whereas the ventral foreskin is deficient, and the shaft of the penis is bent ventrally. The two main problems in hypospadias are:

• the location of the urethra (which can be found on the ventral side of the shaft of the penis, proximal to its correct position)

• chordee (ventral angulation of the shaft and glans) – correction of chordee to straighten the penis is required to allow later successful sexual function. The operation is usually performed as a single-stage procedure at 9–12 months of age, often as day surgery.

Circumcision is absolutely contraindicated in hypospadias because the skin of the foreskin is used during the hypospadias repair. Severe hypospadias may be indicative of an intersex abnormality. For example, when there is penoscrotal hypospadias and a bifid scrotum, the scrotum should be examined carefully for testes, as some of these children may be females with congenital adrenal hyperplasia; the labioscrotal folds are labia rather than scrota, and the presumed urethral opening may in fact be the entrance to the vagina (see Chapter 19.3).

The inguinoscrotal region

Inguinal hernia

A widely patent proximal processus vaginalis allows bowel (and, in girls, the ovary as well) to enter the inguinal canal, producing a reducible lump in the groin called an indirect inguinal hernia (Fig. 9.1.5). This occurs in about 2% of infant boys but is less frequent in girls. The greatest incidence is in the first year of life.

Hydrocele

A hydrocele presents as a painless cystic swelling around the testis in the scrotum (Fig. 9.1.6). It contains peritoneal fluid that has tracked down a narrow but patent processus vaginalis. It transilluminates brilliantly. When the hydrocele is lax, the testis can be felt within it. The upper limit of the hydrocele can be demonstrated distal to the external inguinal ring, distinguishing it from an inguinal hernia where the swelling extends through the external inguinal ring. There is no impulse on crying or straining.

Undescended testis

The diagnosis is made by examining the inguinoscrotal region. Normally, the testis should be found within the scrotal sac. In cryptorchidism the scrotum looks empty (Fig. 9.1.7). The testis is ‘milked’ down the line of the inguinal canal towards the scrotum with the left hand and pulled gently towards the scrotum with the right hand. If the testis cannot be brought into the scrotum, or will not remain there spontaneously, it is considered undescended.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree