Introduction

There are three main reasons why an understanding of substance misuse in pregnancy is important. The first is to appreciate that substance use, misuse, harmful use and dependence are associated with considerable mortality and physical and psychologic morbidity in the mother. The second reason is to understand the likely impact on the fetus, neonate and infant through childhood to adolescence, and even into adult life. The third main reason is to develop effective services, which detect problems early and deliver appropriate interventions.

The terms “substance” and “drug” are used interchangeably. The term “drug” may be used to cover licit substances (tobacco and alcohol) and illicit substances such as central nervous system depressants (opiates and opioids, e.g. heroin and “street” methadone), stimulants (cocaine, crack, amphetamines and ecstasy), volatile substances and cannabis. It includes prescription drugs (such as benzodiazepines) taken in a manner that was not indicated or intended by a medical practitioner, and failing to use over-the-counter preparations such as codeine-based products (e.g. cough medicines, decongestants) in accordance with instructions. A combination of prescribed medications is known as “polypharmacy.” Combinations of substances may result in “polydrug” “misuse,” “harmful use” or “dependence” (or addiction). All may be associated with physical or psychologic co-morbidity [1].

It should be noted that just one dose of a drug can sometimes be fatal and, therefore, any substance “use” must be considered in detail. A working definition of “substance misuse” is the use of substances that is socially, medically or legally unacceptable or that has the potential for harm.

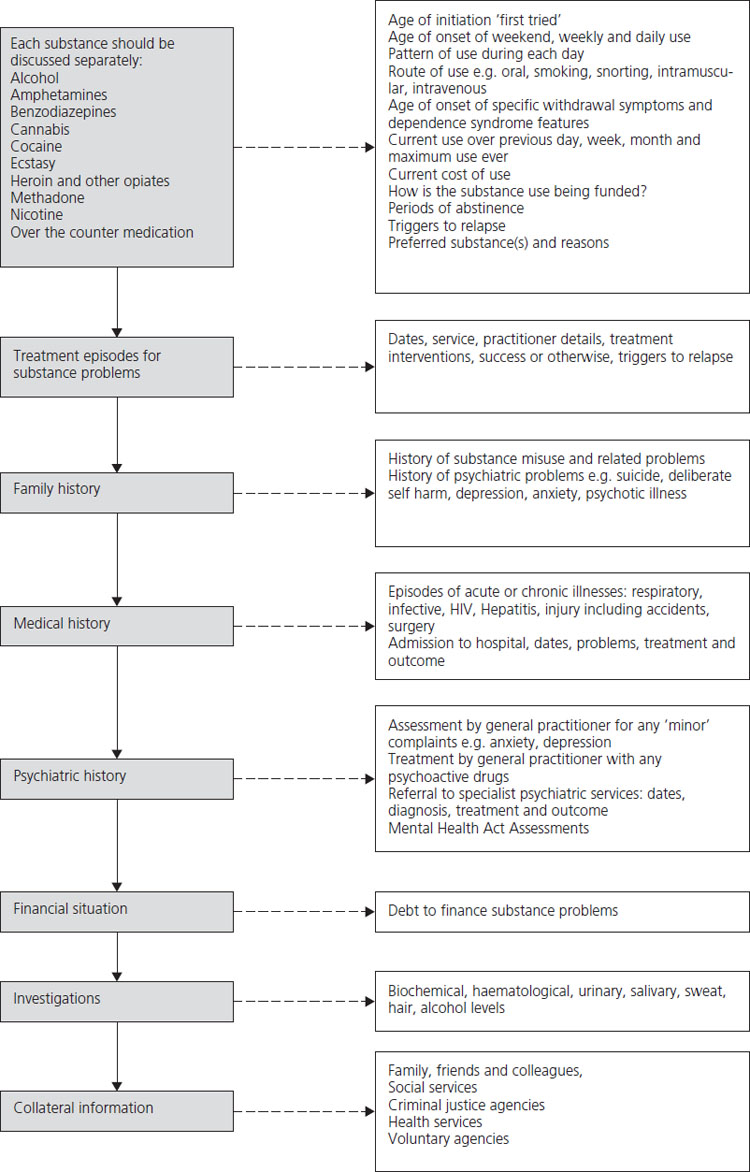

In order to reach a diagnosis, the two similar (though not identical) systems that have emerged are the International classification of diseases (ICD-10) [2] and the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and statistical manual (DSM-IV) [3]. A diagnosis of harmful use can be made if there is a pattern of psychoactive substance use that is causing physical or mental damage to health. A diagnosis of dependence syndrome (or addiction) can be made if three of the criteria outlined in Box 19.1 are present. Table 19.1 summarizes the symptoms of intoxication for commonly misused substances.

Table 19.1 Symptoms of intoxication and withdrawal [224]

Prevalence of substance use in young women

There is great variability in prevalence rates in different countries and regions of countries, and in different ethnic groups [4]. This may be explained in part by differences in definitions, in patterns and modes of use, in screening, assessment and diagnostic tools, the time window during which use is being measured (e.g. lifetime, previous year or previous month usage), measurement techniques, and study settings, as well as by wider environmental influences such as availability, price, social acceptability, seizure and arrest policies.

Box 19.1 Criteria for diagnosis of dependence syndrome (addiction)

- A strong desire or sense of compulsion to take the substance.

- Difficulties in controlling substance use.

- A withdrawal state when substance use ceases, which is relieved by the use of the substance (for details on each substance, please see Table 19.1).

- Evidence of tolerance, i.e. more of the substance is required to give the same effect.

- Neglect of activities and interests in order to obtain substances or recover from use.

- Persisting in substance use, despite evidence of overtly harmful consequences.

Alcohol

In general, abstention rates are consistently higher among women than men. The UK has a relatively low abstention rate (14%, compared with 38% in the USA) [5]. However, drinking among young women is increasing and consumption in many young women is in excess of the sensible drinking benchmarks. Among women aged 16–24 years heavy drinking (above a weekly benchmark of 14 units – see Box 19.2) has more than doubled, from 15% in 1988–89 to 33% in 2002– 3 [6] (one unit = 8 g or 10 mL of alcohol). Among young women in the UK aged 16–24, 40% exceeded three units on at least one day in the previous week [6,7]. This is important information because the safe threshold of drinking in pregnancy is not established and, therefore, comprehensive assessment is essential and extremely careful consideration of appropriate advice is required.

Box 19.2 Units of alcohol

- 1 unit of alcohol is 10 mL or 8 g of alcohol.

- More than 2–3 units of alcohol per day is considered a health concern for nonpregnant women.

- 1 half pint (284 mL) of beer with 3.5–4% alcohol has 1 unit of alcohol.

- 175 mL of wine with 12% alcohol has 2 units of alcohol.

- 25 mL of spirits with 40% alcohol has 1 unit of alcohol.

Illicit substance misuse

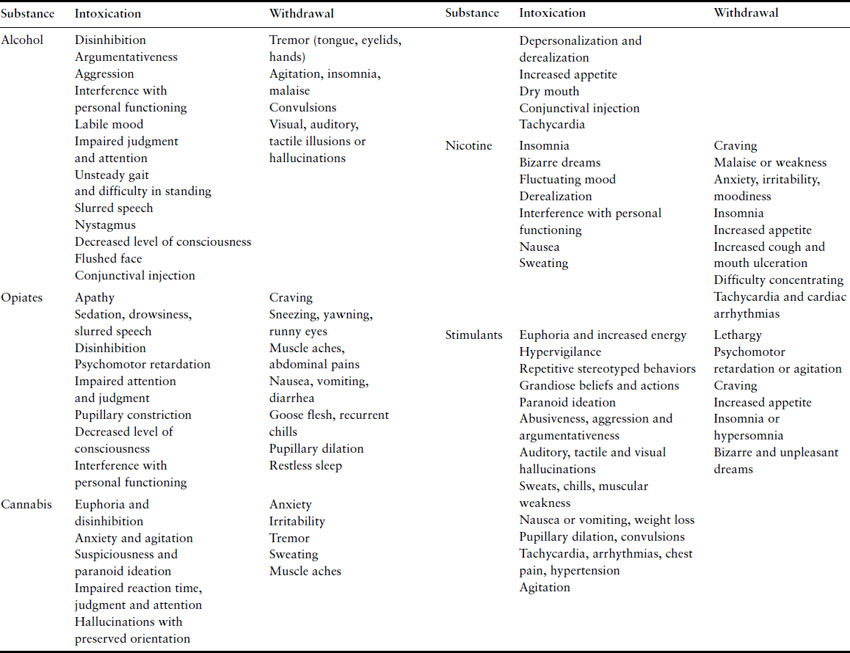

Illicit substance misuse is a substantial problem. A million people in the UK aged 16–59 used class A drugs in the past year and this increased between 1998 and 2005–6 [8]. One and a half million young people in the UK aged 16–24 have used an illicit drug over the previous year. Men more commonly report use. Class A drug use by young women and men remains stable (for details of the classes of substances laid out in the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971, see Table 19.2). However, young women are 1.5–3 times more likely to use substances than older women. International studies demonstrate that about one-quarter to one-fifth of women in younger age groups have used illicit drugs in the past year.

Table 19.2 Summary of the classes of the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971

Nicotine use in young women

There was a fall in the overall prevalence of cigarette smoking between 1998–99 and 2004–5, from 28% to 25% of people aged 16 and over. In 2004–5, 26% of men and 23% of women were cigarette smokers, compared with the early 1970s when around 50% of men and 40% of women smoked. Male smokers smoked more cigarettes a day on average than female smokers. In each year since 1998–99, men smoked on average 15 cigarettes a day compared with 13 for women.

In recent years, girls have been more likely to smoke than boys. In 2004, 7% of boys aged 11–15 in England were regular smokers (that is, they usually smoked at least one cigarette a week), compared with 10% of girls. Since the early 1990s the prevalence of cigarette smoking has been higher among 20–24 year olds than in any other age group in Britain. The proportion of respondents smoking on average 20 or more cigarettes a day fell from 14% of men in 1990 to 9% in 2004–5 and from 9% of women to 6% [9].

Substance use during pregnancy

Alcohol

Alcohol exposure varies from 0.2% to 14.8% depending upon stage of pregnancy, definition of exposure, diagnostic classification and method of assessment. A recent Swedish study reported risky use of alcohol during the first 6 weeks of pregnancy at 15% [10], where risky drinking was defined as drinking more than 70 g/week (see Box 19.2) during any 2 or more weeks and/or two or more episodes of more than 60 g/episode. A Norwegian study demonstrated similar findings: binge drinking was reported in 25% during the first 6 weeks of pregnancy [11]. The behavioral risk factor surveillance system survey in the USA reported that approximately 10% of pregnant women aged 18–44 used alcohol and approximately 2% engaged in binge drinking (five or more drinks on one occasion) or frequent use of alcohol (seven or more drinks per week). It also showed that more than half of the women in this age group who did not use birth control (and therefore might become pregnant) reported alcohol use and 12.4% reported binge drinking [12]. Other findings in the USA, which reveal that 4.1% of pregnant women aged 15–44 report binge drinking in the past month, are broadly consistent [13,14]. This compares to a rate of binge drinking during the past month of 23.2% among nonpregnant women. Moreover, an Australian national survey revealed that 47% of pregnant and/or breastfeeding women were using alcohol up to 6 months post partum [15].

Illicit substance misuse

In the UK, since 6.1% of women aged 16–24 have used a class A drug and 20.6% have used any illicit drug in the past year, there is clear evidence that substance use in this population is an issue of real and potentially serious clinical concern [8].

There is some consistency from several US and Australian studies that report on substance use in pregnancy. The American National Pregnancy Health Survey found that 5.5% of pregnant women were using any illicit drug (cannabis, cocaine, amphetamines, opiates, inhalants, hallucinogens, nonmedical use of psychotherapeutics) [16]. A study using birth certificate reports of substance misuse showed 5.2% of pregnant women to be using illicit drugs [17]. The Australian National Drug Strategy Household Survey reported any illicit drug use in 6% of those women who stated that they were pregnant and/or breastfeeding in the last 12 months [18].

Opiates/opioids

Opiates/opioids/narcotics are taken orally (often from misuse of prescription medications), intravenously or intranasally. Intravenous heroin is a short-acting drug with a half-life of minutes. Withdrawal may begin in as little as 6–8 hours after the last dose is taken. The reported prevalence of opiate use during pregnancy ranges from 1.6% to 8.5% [19,20]. The Maternal Lifestyle Study in the USA [21] reported a prevalence of 2.3% detected through meconium analysis, though there was considerable variation (1.6–7.2%) in the reported prevalence.

Cocaine

Cocaine can be snorted, injected intravenously or subcutaneously or smoked and inhaled as crack cocaine. It is a short-acting drug with peak levels in 15–60 minutes. It readily crosses the placenta. The reported prevalence varies from 0.3% [22] to 9.5% [21]. Cocaine exposure in the UK was reported as less than 1.1% among pregnant women [23–25]. Based on maternal self-report and meconium analysis, one American study reported 9.5% exposure to cocaine [21] while another reported 1.1% of pregnant women to be using this substance [16].

Cannabis

Marijuana is generally inhaled through smoking. Cannabis use among pregnant women varies greatly, from 1.8% [22] to 15% [23]. Between 8.5% and 14.5% of pregnant women in urban UK samples are smoking cannabis at 12 weeks gestation [24,25]. In a perinatal sample from Glasgow, meconium analysis showed that 15% of mothers had used cannabis in the second or third trimester [23] compared with 7.2% in a multicenter American study [21]. The Australian study reported that 5% of those women who stated that they were pregnant and/or breastfeeding in the last 12 months had used cannabis [18]. Since cannabis was used by 16.6% of women aged 16–24 years and 5.9% of those aged 16–59 years during the last year in the UK, the potential impact on the fetus must be considered [8].

Amphetamine

Methamphetamine use is increasing throughout the world. It is used clinically to treat attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. It comes in different forms that may be smoked, swallowed, snorted or injected and may be known as meth, speed or crank. It can be manufactured from common cough and cold remedies. The effects are similar to cocaine but often accompanied by hallucinations. The half-life is much longer than that of cocaine, ranging from 10 to 20 hours. While data about the use of these agents in pregnancy are still evolving, there appear to be an increasing number of infants in Western countries who were exposed to these agents in utero.

Cigarette smoking

Similar methodologic issues to those described above pertain to smoking estimates. However, in industrialized countries, between 20% and 30% of pregnant women report smoking [26]. Between 11% and 48% of pregnant smokers quit at some stage during pregnancy [27–30]. In the UK, an estimated 27% of pregnant women continue to smoke throughout pregnancy [31]. Up to a quarter of women who smoke before pregnancy are likely to stop before their first antenatal visit without professional help. A further 10% are likely to stop following their first antenatal visit. However, the majority of those who do not quit prior to becoming pregnant continue to smoke [32].

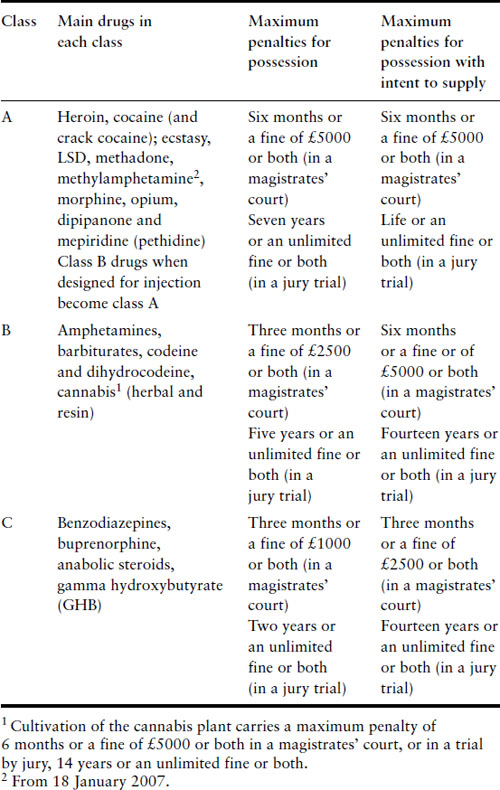

The mortality associated with alcohol and drugs is 9–16 times higher than in the general population and substance misuse is a very strong predictor of completed suicide [33–38]. The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths in the UK from 2002–4 found that, when all deaths up to 1 year from delivery were taken into account, 8% were caused by substance misuse [39] (Figure 19.1). Injecting drug users have a mortality rate 12–22 times greater than that of their peers [35] and age-standardized alcohol-related death rates for women aged 25–44 have tripled over the last 30 years [40].

Figure 19.1 Maternal mortality rate per million maternities from leading causes of death as identified by ONS linkage study for England and Wales; 2000–02.

The interactions of substance misuse with health are multiple and complex. The effects may be very rapid or insidious, by a direct pharmacologic or physiologic action or indirectly due to associated behaviors. Substance misuse, which may involve a range of substances, must be seen in the context of social and medical difficulties. These may include poor diet and nutrition and/or chaotic lifestyle, e.g. homelessness, social isolation, social deprivation, and medical and psychiatric complications [41–43].

Practitioners working with substance misusers need to be aware of the relationship of a history of substance misuse to presenting physical or psychologic problems such as coma, confusion, delirium, memory problems, fever, agitation, convulsions, tremor, paranoia or hallucinations. Substance misusers may have vascular, infectious, carcinogenic or traumatic conditions directly related to their misuse. This may connect previous difficulties to a current acute presentation for which life-saving measures could be required. For these reasons, it is obligatory to establish whether recent substance use (including the types, quantities, route and the time course of use) may have a bearing on overt and covert physical and psychologic symptomatology. Even where the incidence of serious adverse effects is low, it is the unpredictability of these events that makes the health consequences significant.

Alcohol, drugs and nicotine affect all organs of the body, but a detailed account of these physiologic effects is beyond the scope of this chapter [1]. The acute effects of intoxication, as well as the impact of chronic use and including the development of withdrawal and dependence, can lead to an array of physical and psychologic problems and social consequences. Dependence on some substances can develop very rapidly, within weeks or months. Intoxication, addiction and perhaps even an underlying tendency to seek out risk may all work together to further increase high-risk behaviors such as injecting drug use, needle sharing, unsafe sex and the repeated use of substances to the point of intoxication (e.g. binge drinking). The psychologic symptoms or psychiatric syndromes may be either cause or effect. These include behaviors such as impulsivity, aggression and disinhibition and disorders including anxiety, depression, psychotic illness, post-traumatic stress disorder, personality disorder and eating disorders. Self-harm may result, with eventual suicide. These difficulties can lead to homelessness, unemployment, poverty and criminality, as well as disengagement from families, communities and services. Patients with co-morbid conditions have a poorer prognosis and place a heavy burden on services because of higher rates of relapse and rehospitalization, serious infections such as hepatitis and HIV, prostitution, violence, arrest and even imprisonment.

It should be borne in mind that co-morbid conditions might constitute up to 75% of some clinical populations [36]. In the National Treatment Outcome Study [37], as in other studies, females were more likely to report a co-morbid psychiatric condition, especially depression or borderline personality disorder, whilst males were more likely to suffer from antisocial personality disorder. Compared with controls, pregnant women with affective disorder or schizophrenia still smoke very heavily [44].

The impact of ethnic and cultural factors must be considered when undertaking an assessment of pregnant women, as their substance-using behavior may be a marker of other attitudes and behaviors that could influence their perceptions of pregnancy and health. In the UK, ethnic minorities use alcohol less than whites, but those of mixed ethnicity use drugs more frequently [45–48].

Effect of substance misuse on pregnancy and the neonate (Table 19.3)

Table 19.3 Fetal and neonatal effects of substance misuse (modified) [71,147,225,226]

| Substance | Fetal and neonatal effects |

| Alcohol | Abortion, microcephaly, growth restriction (IUGR), orofacial clefts, neonatal unit admissions, low APGAR scores, cognitive dysfunction and behavioral abnormalities |

| Cigarette smoking | IUGR, preterm birth, placental abruption and (possibly) oral clefts and digital anomalies |

| Cannabis | Shorter gestation and low birthweight |

| Cocaine | In utero hyperactivity, symmetric IUGR, placental abruption, cerebral infarctions, neonatal necrotizing enterocolitis |

| Opiates | IUGR, reduced breathing movements, preterm delivery, preterm rupture of membranes, intrauterine withdrawal |

| Metamphetamine | Growth restriction |

Substance misusers are poor candidates for pregnancy. They are frequently underweight, anemic and socially disadvantaged. They are often poor attendees to antenatal clinics and young users tend to present to maternity services late in their pregnancies. Substance misuse also increases the risk for other conditions, for example sexually transmitted diseases, hepatitis B, hepatitis C, HIV and domestic violence. These associated problems can, in themselves, present a significant risk to the pregnant mother and her unborn child. Moreover, intravenous drug users are at increased risk for cellulitis, phlebitis, thrombosis, endocarditis, septicemia, septic osteomyelitis and, importantly, difficult intravenous access. Substances may affect the growth and maturation of the fetus [49,50].

Alcohol misuse

Antenatal alcohol use is the leading preventable cause of birth defects, growth restriction and neurodevelopmental disorders [51] yet half of all pregnant women report drinking before pregnancy; one-fifth of these drink at moderate or high levels and one-fifth report that they continue drinking throughout the pregnancy [52,53]. There is evidence that those reporting moderate alcohol intake (≥5 drinks per week) are at increased risk of first-trimester spontaneous abortion and stillbirth [54,55]. A recent review has established that alcohol in pregnancy is an important factor independently associated with an increased incidence of a broader range of congenital anomalies than was previously recognized [Box 19.3] [56].

Estimates vary as to the incidence of children affected by prenatal alcohol exposure. A reasonable conclusion based on a review of US data would be that around 1 in 1000 infants is born with the full fetal alcohol syndrome (defined below) and that 1 in 100 is born with some features of the effects of alcohol (fetal alcohol spectrum disorder). These abnormalities may include facial dysmorphic features, cognitive abnomalities, central nervous system abnormalities, birth defects or growth restriction [57–61].

Stratton et al. have developed diagnostic criteria for fetal alcohol syndrome [59].

Box 19.3 Some facts about alcohol use in pregnancy

- Up to 15% of women may be using alcohol.

- About 5% may be using illicit drugs.

- The proportion of women using substances is less at term compared with in the early stages of pregnancy.

- Substance use rises sharply in the first six months postpartum.

- Detection of substance use in obstetric units is low.

- Effective screening and intervention strategies should be implemented.

- Confirmed maternal alcohol exposure.

- Evidence of a characteristic pattern of facial anomalies that includes features such as short palpebral fissures and abnormalities in the premaxillary zone (e.g. flat upper lip, flattened philtrum, flat midface).

- Evidence of growth retardation, as in one of the following: (a) low birthweight for gestational age, (b) decelerating weight over time not due to nutrition, (c) disproportional low weight to height ratio.

- Evidence of CNS neurodevelopmental abnormalities, as in at least one of the following – decreased cranial size at birth, structural brain abnormalities (e.g. microcephaly, partial or complete agenesis of the corpus callosum, cerebellar hypoplasia), neurologic hard or soft signs (as age appropriate), such as impaired fine motor skills, neurosensory hearing loss, poor tandem gait or poor eye–hand co-ordination.

Central nervous system effects include hyperactivity and attention deficits and poor impulse control, as well as language and motor development delays [62]. Affected children continue to manifest developmental disabilities, psychiatric disorders and cognitive delay as they mature. In terms of dysmorphic features, those who were more severely damaged also showed the more prevalent and marked psychiatric symptoms. Milder difficulties, such as poor attention span, distractibility and poorer performance on IQ and neurobehavioral tests, were noted in mothers drinking more than 250 g of alcohol per week. In a follow-up study, Streissguth et al. identified dose–response effects of alcohol prenatally on neurobehavioral attention, speed of information processing and learning function at 14 years [63].

There is no conclusive evidence of adverse effects on either growth or IQ at levels of consumption below 120 g (15 units) per week. However, Day & Richardson note a linear relationship between growth and alcohol use below one drink a day [64]. Interestingly, children who live in privileged environments can make up these deficits as they develop. However, although one study reported that binge drinking does appear to increase behavioral characteristics that might predispose to later dysfunction [65], it should be noted that a meta-analysis of prenatal alcohol exposure and infant mental development has urged caution in interpreting this relationship because of the small, inconclusive literature and heterogeneity in analytic techniques and measurements [66].

There is also recent evidence that maternal alcohol misuse, particularly during early pregnancy, is associated with adult alcohol disorders in the offspring [67,68]. Furthermore, some very intriguing work by Zhang and colleagues describes the adverse impact of alcohol on immune competence and the increased vulnerability of alcohol-exposed offspring to the immunosuppressive effects of stress. These researchers postulate that fetal programming of hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity may underlie some of the long-term behavioral, cognitive and immune deficits that are observed following prenatal alcohol exposure [69]. Nonetheless, despite lack of certainty regarding the immediate, short- and long-term effects of alcohol on the fetus and later development, it is recommended that women should be careful about alcohol consumption in pregnancy and limit this to no more than one standard drink per day [70].

Illicit substance misuse

Using record linkage methodology, Burns et al. have confirmed that births in drug misusers (opioids, stimulants or cannabis) occurred in women who were younger, had a higher number of previous pregnancies, were indigenous, smoked heavily and were not privately insured [71]. These women also presented later to antenatal services and were more likely to arrive at hospital without having had any antenatal care. Neonates were more likely to be premature and admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit and special care nursery. This is in keeping with the findings of the National Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths in the UK [39] and other studies [72].

Opiates/opioids

A classic opiate abstinence withdrawal syndrome occurs in at least 50% of babies born to mothers using opiates. No clear teratogenic effect has been identified, although consistent findings include low birthweight, prematurity and reduced intrauterine growth [73]. Heroin is a short-acting opiate and many of the problems associated with its use result from withdrawal effects. Withdrawal causes contraction of smooth muscle; this can lead to spasm of the placental blood vessels, reduced placental blood flow and, consequently, reduced birthweight in babies. However, methadone, the opioid substitute, has a longer lasting effect, thus eliminating fluctuations in blood levels and leading to less severe withdrawals.

Cocaine

Maternal cocaine use is associated with restricted intrauterine brain growth [73,74] and placental abruption [75]. These complications probably occur secondary to its powerful vasoconstrictor effect. Cocaine use during pregnancy does not cause withdrawal symptoms in the newborn baby. However, Scher and colleagues [49,50] have reported electroencephalographic effects at birth and 1 year. There is some evidence [76] that prenatal cocaine use is associated with specific cognitive impairment at 4 years of age. However, cocaine effects on cognitive function can be related to associated environmental risk, social status and exposure to multiple and cumulative risks, which compromise outcomes and may overshadow any prenatal effect from cocaine [77].

Amphetamines and ecstasy

“Ecstasy” is associated with congenital cardiovascular and musculoskeletal abnormalities [78]. However, there is no evidence that use of either amphetamines or ecstasy directly affects pregnancy outcomes, although, again, there may be indirect effects due to associated problems. Amphetamines and ecstasy do not cause withdrawal symptoms in the newborn baby. Prenatal exposure should be seen as a possible marker for multiple medical and social risk factors, such as social isolation, maternal psychopathology, violence and child abuse.

Methamphetamine is an increasing problem. A study by Smith et al. has exposed a three times greater likelihood of being small for gestational age than in an unexposed group, after adjustment for co-variates [79].

Cannabis

Cannabis is frequently used together with tobacco and the latter could be the main contributor to the associated side effects. Cannabis exposure has been linked to shorter gestation and low birthweight and later effects on the central nervous system, cognitive development and behavior [49,80,81]. A mild withdrawal syndrome has been reported and disturbed sleep with potentiation of the effects of alcohol on the fetus has been described [82,83]. Moreover, a recent report suggests that prenatal exposure is a significant predictor of marijuana use at age 14 [84].

Benzodiazepines

Benzodiazepine use has been associated with poorer outcomes (especially low birthweight, premature birth, cleft lip and cleft palate). Benzodiazepine misuse during pregnancy also causes withdrawal symptoms in the newborn baby, which can be particularly severe if there is “poly” drug misuse [85]. However, once again, its use is frequently associated with medical and social problems, making it difficult to know whether these adverse effects are a direct result of the substance or of the related difficulties.

Solvents

Limited attention has been paid to these easily obtainable substances, which may be associated not only with behavioral problems, CNS stimulation and disinihibition in the mother, but also with fetal growth restriction, preterm delivery and perinatal mortality [86].

Cigarette smoking and nicotine

Smoking is a common occurrence in drug and alcohol users, making it difficult to be certain that the effects ascribed to drugs are not wholly or partly due to cigarettes. The amount of daily smoking prior to pregnancy also seems to be associated with spontaneous abortion [87]. Cigarette smoking during pregnancy results in low birthweight and intrauterine growth restriction associated with developmental delay. It has even been suggested that the reduction in birthweight secondary to tobacco is greater than that due to heroin [85]. A recurring theme is the association between maternal smoking during pregnancy and sudden infant death syndrome [73] and the correlation of passive smoking with respiratory difficulties in infants [88]. The use of snuff or nicotine substitutes has also been investigated, but there is no significant impact on birthweight, though there is a slight increase in congenital malformation [89,90]. Duration of smoking, exposure to environmental smoke (such as smoking in partners and family), self-efficacy and educational status have been demonstrated to influence the mother’s reduction in nicotine use during and after pregnancy [91]. It is notable that the background socio-economic status factors also require attention [89]. See also Chapter 1.

The impact of parental substance misuse on children

Long-term developmental neurocognitive, physical and psychosocial effects resulting from in utero exposure to opioids and other drugs are poorly understood. Moreover, it is increasingly common that substance misusers take a combination of different drugs at different times during their pregnancy and, because of the complex psychosocial context in which they use substances, such research can face serious methodologic problems. However, generally, parental substance misuse poses significant risks for children. Child and adolescent mental health services report that a parent’s long-standing drug and/or alcohol misuse is a substantial risk factor for poor mental health in children [92]. Children may also be at high risk of maltreatment, emotional or physical neglect or abuse, family conflict, and inappropriate parental behavior [93–95]. Children may be exposed to, and involved in, drug-related activities and associated crimes [96]. They are more likely to display behavioral problems [97], experience social isolation and stigma [98], misuse substances themselves when older [99], and develop problem drug use [100].

Parents with chronic drug addiction spend considerable time and attention on accessing and using drugs, which reduces their emotional and actual availability for their children. Conflicting pressures may be especially acute in economically deprived, lone-parent households and where there is little support from relatives or neighbors [101]. In the long term, children of substance-misusing parents may have severe social difficulties, including strong reactions to change, isolation, difficulty in learning to have fun and estrangement from family and peers [95]. Despite this, substance misusers should not automatically be stereotyped as poor parents.

Effect of pregnancy on substance misuse

Pregnancy may motivate individuals to spontaneously modify their behaviors or to be susceptible to advice for the health of the baby [102]. Indeed, about two-thirds of American women who drank prior to conceiving, as well as up to 40% of those who smoked, stopped spontaneously during pregnancy [103]. In the USA, the 1995 behavioral risk factor survey showed that 51% of women of childbearing age drank prior to pregnancy, but only 16% drank during pregnancy [103]. A telephone survey of pregnant women found that 65.6% were drinking before pregnancy compared with 5.2% during pregnancy [104]. Hispanic ethnicity and younger age were significantly associated with spontaneous alcohol abstinence. The Australian national data [18] showed that women who were pregnant either abstained from alcohol (38%) or drank less (59%). It is encouraging to note that only 3% continued to drink the same amount of alcohol after becoming pregnant.

Among those who smoked prior to pregnancy 39% quit after becoming pregnant, a rate eight times that reported among smokers in the general population [105]. Among low-income, predominantly unmarried American women, spontaneous cessation of smoking and alcohol was reported by 28% and 80% of the women respectively. Factors associated with decreased likelihood of spontaneous smoking cessation in pregnancy such as less education [27,106], less concern about the effects of smoking on the fetus [107], worse mood or emotional well-being [108], having partners who smoke [109,110], and greater severity of addiction [27] could also be relevant to other substances.

Research has also shown that up to 60% of those who stop smoking when pregnant will return to smoking within the first 6 months post partum and 80–90% will have experienced a relapse by 12 months post partum [105,111]. There is some indication that this might be applicable to drugs and alcohol. A longitudinal study of pregnant substance users found that the use of cigarettes, alcohol and marijuana was lowest during pregnancy, increased sharply at 6 months post partum and remained level at 12 months post partum [112]. Although the evidence demonstrates that the proportion of women using substances is less at term compared with in the early stages of pregnancy, which might indicate that use of substances diminishes as pregnancy advances, this has not been studied in a longitudinal design over the long term.

Box 19.4 Challenges to antenatal screening

- Late booking

- Irregular attendance due to social problems, homelessness or chaotic lifestyles

- Attendance at different hospitals

- Concealment of drug problems because women may perceive services to be judgmental or due to the concern that they may lose their children

- Reluctance to provide samples

- Concerns of obstetricians and midwives regarding screening possibly due to:

- lack of training in this field

- lack of time

- worries about interfering with their relationship with antenatal women

- difficulties in accessing treatment services for women with addictions

- lack of training in this field

Overarching principles of treatment

The main objectives of a pregnant drug users (PDU) service are a safe pregnancy with a healthy baby and mother – the welfare of both the unborn child and the mother is a paramount consideration. In order to achieve this, promotion of engagement with substance misuse treatment and antenatal care within a co-ordinated framework is a key concern (Box 19.4). This should involve different phases of reproductive healthcare: preconception, pregnancy, childbirth and postnatal (including parenting) [113]. In this chapter we will focus on management during pregnancy and childbirth.

In order to develop the optimal treatment plan, the substance problem must be recognized by professionals and acknowledged by the patient. It is well documented that a substantial number of women treated in obstetric settings have unrecognized and untreated psychiatric disorders, as well as substance use [114].

All pregnant women should be screened for substance misuse. Questions should be asked in a nonjudgmental manner, beginning with inquiries about legal substances, followed by illegal ones beginning with marijuana. Patients who admit to substance misuse should be asked to quantify their use and about route of administration. As terminology varies by region and changes with time, practitioners should be comfortable asking patients to explain terms with which they are unfamiliar [224, 227].

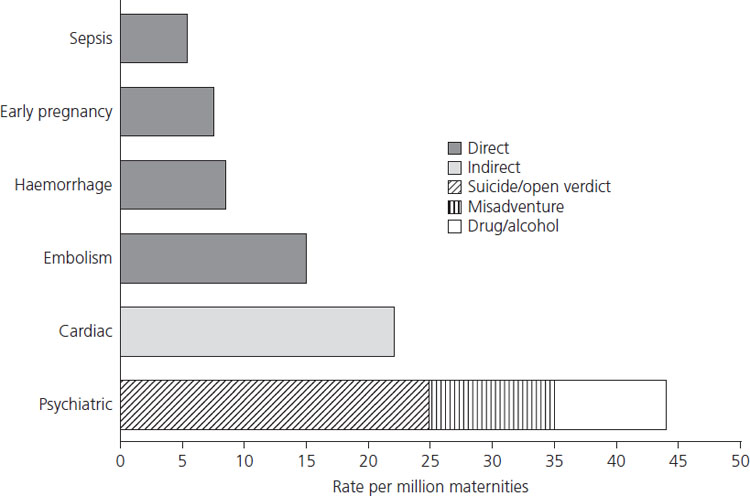

Routine antenatal assessment is unlikely to detect all women with a past or present history of alcohol and/or illicit drug misuse (Figures 19.2 and 19.3). Various studies have underlined the poor detection rate of fetal alcohol syndrome (FAS) in general practice and by obstetricians and pediatricians [115]. In one study, less than half of the general practitioners studied were competent in the recognition of FAS [116]; 73% of obstetric case notes made no record of maternal alcohol consumption (despite the mothers being known to be in a high-risk group) and routine pediatric care did not identify cases from high-risk mothers that had been detected by a trained researcher [117].

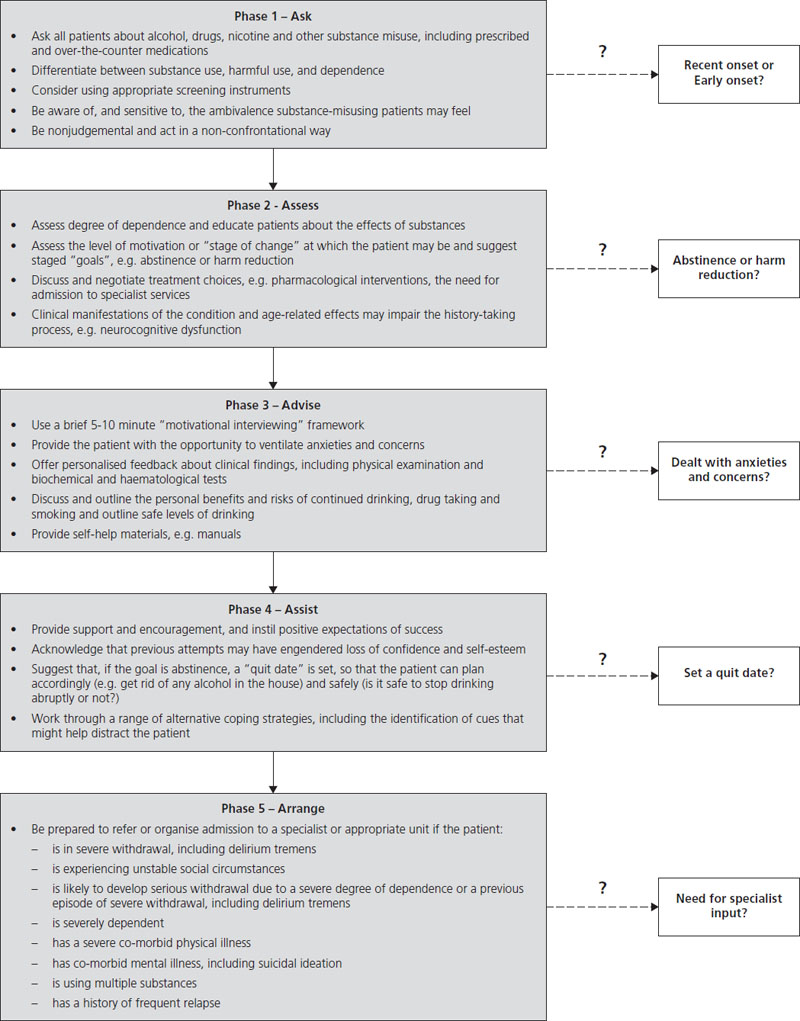

Figure 19.2 Suggested outline for schedule of issues to be covered in assessment. Adapted from Raw et al. [227].

Self-report as a measure of substance misuse is unreliable and could potentially lead to underestimation of the problem. Screening questionnaires have been shown to identify correctly more than two-thirds of current prenatal drinkers, only 20% of whom were identified and documented in obstetric records [118]. An intensive screening interview in Sweden has been able to detect five times more antenatal women as drinking excessively compared with regular antenatal screening [10]. In the case of illicit drugs, biologic markers are more reliable [119] but test accuracy is dependent upon the tissue tested and the type of substance misused. Urine analysis can lead to false-negative results if the duration between the last drug use and providing of urine sample is prolonged. Hair analysis has a high sensitivity for opiates and cocaine but low for cannabis; it is also associated with a 13% false-positive rate for cocaine and opiates, which may be due to passive exposure [120]. Table 19.4 lists the duration of a positive urine drug screen after use for some commonly misused substances.

Table 19.4 Duration of positive urine drug screens after use

| Drug | Duration |

| Amphetamines | 48 hours |

| Alcohol | 12 hours |

| Barbiturates | 10–30 days |

| Diazapam (Valium) | 4–5 days |

| Cocaine | 24–72 hours |

| Heroin | 24 hours |

| Marijuana | 3–30 days |

| Methaqualone | 4–24 days |

| Phencyclidine | 3–10 days |

| Methadone | 3 days |

The CAGE, AUDIT and TWEAK questionnaires have been identified as optimal for identifying problem alcohol use in antenatal settings [121]. The AUDIT-C (a brief version of the AUDIT) [122] and the T-ACE (a modified version of the CAGE questionnaire) [118] have also proved useful in pregnancy and are reviewed in Box 19.5 and Box 19.6. The use of biomarkers, though helpful in the detection of alcohol use in pregnancy, requires more development [123].

Management of substance misuse in pregnancy

The most important issue is to be able to determine whether patients are engaging in harmful use or are dependent on one or more substances. This differentiation is critical in terms of decisions around the selection of appropriate treatment interventions (in terms of type and intensity) and suitability of settings. It is also important when designing and assessing research because a range of terms may be used that do not equate to each other, so that the findings are not comparable.

Box 19.5 AUDIT-C (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test © WHO 1990)

Q1: How often did you have a drink containing alcohol in the past year?

| Answer | Points |

| Never | 0 |

| Monthly or less | 1 |

| Two to four times a month | 2 |

| Two to three times a week | 3 |

| Four or more times a week | 4 |

Q2: How many drinks did you have on a typical day when you were drinking in the past year?

| Answer | Points |

| None, I do not drink | 0 |

| 1 or 2 | 0 |

| 3 or 4 | 1 |

| 5 or 6 | 2 |

| 7 to 9 | 3 |

| 10 or more | 4 |

Q3: How often did you have six or more drinks on one occasion in the past year?

| Answer | Points |

| Never | 0 |

| Less than monthly | 1 |

| Monthly | 2 |

| Weekly | 3 |

| Daily or almost daily | 4 |

The AUDIT-C is scored on a scale of 0–12 (scores of 0 reflect no alcohol use). In men, a score of 4 or more is considered positive; in women, a score of 3 or more is considered positive. Generally, the higher the AUDIT-C score, the more likely it is that the patient’s drinking is affecting his/her health and safety.

Box 19.6 TACE screen for alcohol problems

| T | Tolerance: How many drinks does it take to make you feel high? |

| A | Have people annoyed you by criticizing your drinking? |

| C | Have you ever felt you ought to cut down on your drinking? |

| E | Eye-opener: Have you ever had a drink first thing in the morning to steady your nerves or get rid of a hangover? |

The TACE, which is based on the CAGE, is valuable for identifying a range of use, including lifetime use and prenatal use, based on the DSM–IIIR criteria. A score of 2 or more is considered positive. Affirmative answers to questions A, C, or E = 1 point each. Reporting tolerance to more than two drinks (the T question) = 2 points.

Whatever the available options, they need to be discussed and agreed with the patient, the patient’s partner (if feasible), and the multidisciplinary team. Regular individual monitoring and attendance are a priority. Liaison with other services is essential. Group work has the benefit of providing a social network and group cohesion, and may more efficiently support both health education (about effects of substance misuse on mother and baby, diet and nutrition, health visitors, sexual health), and support with core problems (e.g. housing, benefits). However, some mothers prefer individual treatment.

Available options

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree