Submersion Injury

Pamela J. Okada and M. Douglas Baker

EPIDEMIOLOGY

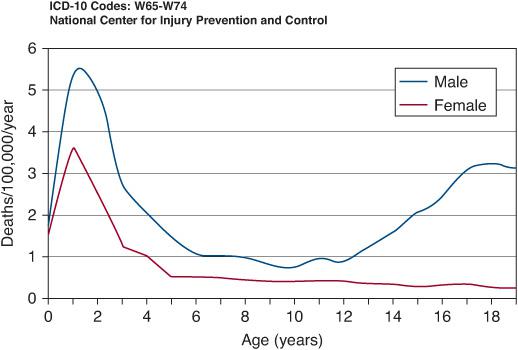

Submersion injury is a major public health problem and accounts for more than half a million deaths annually worldwide.1 It is the second most common cause of unintentional death in the United States for children between ages 1 and 19 years (Fig. 117-1), second only to motor vehicle crashes. In 2002, there were 3447 unintentional submersion deaths in the United States, averaging 9 people per day.3 Of these, 1158 (34%) were children. It is estimated that for each submersion death, there are up to four children who receive emergency medical care for nonfatal submersion injuries. More than 40% of these children are hospitalized and 20% of the survivors suffer permanent disability.

Submersion injury risks vary by gender, age, race, and socioeconomic status. After the first year of age, US males are at greater risk of death from submersion than females (Fig. 117-1). Among females, submersion deaths peak at 1 year and decline thereafter. Male incidence patterns exhibit a bimodal distribution, with peaks in ages 1 to 4 years and in the adolescent age ranges. Between the ages of 10 to 19 years, African American males have a higher submersion injury rate than do Caucasian males.3

FIGURE 117-1. Unintentional submersion deaths ages 0–19 per 100,000 per year (2000–2005, USA. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control).

Within the pediatric population, submersion circumstances vary by age group. Children under age 1 year are most likely to drown in bathtubs, toilets, or other household water reservoirs such as large buckets.9 In most cases, bathtub submersions result from a lapse in adult supervision, although not infrequently they are the result of intentional injury.15-18

Industrial buckets, especially the 3- to 5-gallon buckets with a wide base, are an often-overlooked hazard to older infants and toddlers.19-22 Curious children may find themselves headfirst in the bucket, unable to push themselves out of the bucket or tip it over.

Children ages 1 to 4 years are most likely to experience a submersion injury in swimming pools and hot tubs, whereas older children are most likely to drown in natural freshwater bodies such as rivers and lakes. Adolescents often drown in rivers, lakes, and canals. Adolescent males tend to participate in riskier recreational activities and to fall under the influence of alcohol and drugs that impair judgment.23-25

Submersion occurrences also exhibit temporal variations. Two thirds of children less than 15 years drown during the warmer months of May through August in the United States and November through January in Australia.33 Submersion injury occurs more frequently on the weekends and between noon and 8 pm.34

Certain medical conditions, such as autism,36 inherited long QTc syndrome,37,38 or epilepsy,39 that may result in loss of consciousness while bathing or taking part in water-related activities predispose children to submersion injury. Sixty percent of submersions involving epileptic patients occurred during an unsupervised bath at home.39 Therefore, older children with epilepsy are encouraged to take showers instead of baths.

SUBMERSION INJURY: DEFINITIONS AND CLASSIFICATION

A number of definitions have been used to describe the submersion or drowning event, incorporating characteristics of the event, pathophysiology, and outcomes. The terminology was confusing and inconsistent. Currently accepted definitions are that drowning is “a process resulting in primary respiratory impairment from submersion or immersion in a liquid medium.” The drowning process is “the continuum that begins when the victim’s airway lies below the surface of the liquid, usually water,” until the time the victim is rescued and given appropriate resuscitative measures. At this point the drowning process is interrupted. Terms including dry or wet drowning; active, passive or silent drowning were abandoned. The word drowned refers to a person who died from drowning. Immersion is to be covered in water; thus for drowning to occur, at least the face and airway are immersed. Submersion implies that the entire body, including the airway, is under water.2 A more detailed discussion of definitions is available electronically and in eTable 117.1  and eFigure 117.1

and eFigure 117.1  .

.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS OF SUBMERSION INJURY

RESPIRATORY MANIFESTATIONS

RESPIRATORY MANIFESTATIONS

Submersion usually initiates a complex sequence of behavioral and reflex responses, including panic, frantic attempts to surface, and breath holding. Younger victims, however, may not struggle, but simply sink and drown quietly. When fluid comes in contact with the mucosa of the larynx, laryngospasm typically ensues, but this protective reflex is short lived and water can soon be aspirated into the trachea and distal airways. This is contrary to common wisdom that laryngospasm prevents water aspiration in majority of victims, who go on to die of hypoxia without water entering the lungs.46 Determinations of lung weights and volumes from autopsies of drowned victims have shown evidence of death without aspiration of water in about 2% of the cases.47

The traditional teaching that seawater draws water from the intravascular spaces into the lungs by osmosis, resulting in fluid-filled alveoli and hypovolemia, and freshwater results in water absorption into the vascular space and hyper-volemia and hemolysis is based on impeccable physiologic reasoning. It is, however, rarely corroborated by empirical observation, perhaps because most survivors do not aspirate sufficient volumes of liquid to justify these changes. Similarly, it stands to reason that water entry into the lungs should wash out pulmonary surfactant or inactivate surfactant’s surface tension properties.46,49,50 Once again, the extent to which surfactant deficiency contributes to the alveolar collapse and gas exchange abnormalities seen after submersion injuries is not well defined. As in other forms of respiratory disease, ventilation-perfusion mismatch is the primary underlying mechanism of the hypoxemia and hypercapnia found in submersion victims.

Victims may aspirate not only water (fresh- or seawater), but also foreign materials contained in the water and stomach contents.55 Often the victim swallows large amounts of water during the submersion event. A distended stomach makes vomiting common during the resuscitation. Because the victim is unconscious and the airway is unprotected, the results can be catastrophic. Aspiration of gastric contents causes inflammatory damage to the lung parenchyma and compounds gas exchange abnormalities. It may also further predispose the victim to pulmonary infections caused by oropharyngeal organisms.56

NEUROLOGIC MANIFESTATIONS

NEUROLOGIC MANIFESTATIONS

Brain hypoxia, secondary to hypoxemia, ischemia, or both, is the main mechanism for neurologic dysfunction in submersion victims, but both rescuers and clinicians need to be alert for the possibility of concurrent trauma or neurologic disease (eg, seizures resulting in loss of consciousness before drowning). The manifestations of the hypoxic injury are often immediate and severe, displaying the entire spectrum found in other forms of hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy (see Chapter 104). Decreased consciousness is the rule in all patients who have suffered a severe insult. Coma, decreased respiratory drive, decorticate and decerebrate responses, and seizures are common. Brain edema and herniation may occur in severe cases. The pessimistic or, at best, uncertain prognosis of the neurologic dysfunction usually dominate the clinical course after the initial resuscitation, when the shock of the accident is replaced by a waiting vigil for days, or even weeks, until the extent and prognosis of the neurologic injuries can be defined.

CARDIOVASCULAR MANIFESTATIONS

CARDIOVASCULAR MANIFESTATIONS

Cardiac dysrhythmias, cardiac dysfunction, and hypotension are caused primarily by hypoxemic or ischemic hypoxia of the myocardium. Increases in systemic and pulmonary vascular resistances have been described,52,57 but they tend to be incidental and subside after appropriate ventilation and oxygenation have been restored. Hypothermia can cause hypotension and bradycardia; the latter should not be interpreted automatically as a more ominous sign of brain herniation.

OTHER SYSTEMS

OTHER SYSTEMS

Although much has been written about the fluid shifts produced by freshwater (hypotonic) and seawater (hypertonic) on circulating blood volume and electrolyte balance, clinically significant alterations in blood volume or electrolyte concentrations are rare after submersion events.

Hemodilution or hemoconcentration seldom occur and, if present, may relate to ingestion of large volumes of water.46,58,64 Anemia should always raise suspicion of an occult hemorrhage from associated trauma.

TREATMENT

The primary goal of the resuscitation after a submersion injury is to restore adequate oxygenation, ventilation, and circulation. Treatment should begin at the scene. If possible, rescue breathing should be initiated while subject is still in the water.65,66 In diving or boating accidents and in any other instance when trauma is possible (including unwitnessed events), the cervical spine should be immobilized and a jaw thrust maneuver should be used as the method of choice to open the airway. Clearing the mouth and airways of water is unnecessary before rescue breathing. All other resuscitative measures should be instituted according to current pediatric advanced life support protocols until arrival at the nearest medical facility.

Although the specter of brain injury tends to overpower all the other consequences of severe submersion injury, the fortunate reality is that a majority of victims will arrive at the emergency department awake, alert, and having sustained no apparent injury. Even in those cases, it is appropriate to administer 100% oxygen with a nonrebreathing mask. Wet clothes should be removed and other warming measures should be applied as needed. A thorough physical examination and a detailed history are essential to define the circumstances of the event and to identify traumatic injuries that may not be apparent initially. Depending on the history and whether respiratory manifestations develop, a chest radiograph may provide helpful information. However, routine radiographs and laboratory tests are usually unnecessary in the asymptomatic victim.

Victims who develop signs of respiratory distress should be managed in a manner as with any other child with respiratory disease (see Chapters 102 and 109). For the spontaneously breathing patient, 100% oxygen should be given by a nonrebreathing mask. Bi-level positive airway pressure (BiPAP), or continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP) can be useful in patients with more severe respiratory dysfunction, but endotracheal intubation and mechanical ventilation are indicated whenever there is difficulty maintaining the natural airway or there is evidence of impending respiratory failure. If aspiration of gross particulate material is suspected, removal via bronchoscopy may be indicated once the patient is sufficiently stable to tolerate it. Currently, there is no evidence to support the prophylactic use of corticosteroids or antibiotics.46,56,79 Daily assessment of the tracheal aspirate for leukocytosis may be helpful to identify infection, but the presence of leukocytosis is not a specific indicator for infection after aspiration injury.

Circulatory dysfunction is usually the result of hypoxia and therefore tends to be associated with neurologic injuries. It should be treated aggressively to minimize the compounding effect of ischemia on already injured tissues. Inotropic and vasoactive medications are often required to support blood pressure and improve perfusion, but, unless other injuries are present, in most patients circulatory function improves rapidly once blood volume is restored and the myocardium recovers from hypoxia.

In the unfortunate children who present with neurologic dysfunction, the prevention of secondary brain injury is perhaps the most important priority. Intubation of the trachea and institution of mechanical ventilation are usually indicated to minimize the risk from an unprotected airway or a depressed respiratory drive. Placement of a nasogastric tube is recommended to minimize the risk of vomiting and decompress the stomach and intestine. Seizures are common after severe injuries and should be treated with anticonvulsants.

Hypothermia is a common problem in children after a submersion event,81 particularly in cold climates. Esophageal or bladder temperature probes are helpful to monitor the rewarming process, which should be started as soon as possible.49,81 Passive rewarming measures (removal of wet clothing, placement of dry blankets) depend on the child’s ability to produce heat and are often inadequate. Active external re-warming with conventional warmed blankets, heating pads, radiant warmers, and heat lamps is more successful, particularly if the circulation is not impaired and the skin is well perfused. Core rewarming methods are the most efficient, and include administration of warmed IV fluids (36°C–40°C); inhalation of warmed humidified gas mixtures; and performance of gastric, bladder, pleural, or peritoneal lavage with warm saline. Institution of cardiopulmonary bypass or ECMO has been used successfully in children with severe hypothermia and circulatory dysfunction.74,75,78 Complications of rewarming include hypotension, shock, and arrhythmias.

PROGNOSIS

The neurologic injuries are by far the main outcome determinant after submersion injuries. Many clinical investigators have proposed scoring systems and identified prognostic factors that may improve our ability to make predictions (Table 117-1). Although these efforts are helpful, one overwhelming consideration emerges from all the studies as well as from the collective experience of a majority of clinicians: Unresponsiveness following cardiopulmonary resuscitation carries a very poor prognosis for neurologic recovery.

Table 117-1. Factors Associated with Poor Neurologic Outcome after Childhood Submersions in Nonicy Water