Structural Abnormalities of the Female Reproductive Tract

Marc R. Laufer

The development of the female reproductive tract is a complex process that involves cellular differentiation, migration, fusion, and canalization with probable apoptosis (programmed cell death). This integrated series of events creates numerous possibilities for abnormal development and anomalies. Structural anomalies of the female reproductive tract become apparent at varying chronologic times during life, and the diagnosis and treatment may not be straightforward. Most anomalies involving the external genitalia are apparent at birth (see Chapter 3), while obstructive and nonobstructive anomalies of the reproductive tract can be apparent at birth; during childhood, puberty, menarche, or adolescence; or later in adult life.

In this chapter, the normal embryologic development of the female reproductive tract will be presented, followed by anatomic and clinical descriptions of developmental anomalies. Anomalies of the reproductive tract can be remembered with the assistance of the mnemonic CAFE, which stands for canalization, agenesis, fusion, and embryonic rests. These congenital anomalies result from defects of lateral and vertical fusion of the urogenital sinus and müllerian duct systems. In addition, the diagnosis, management, and treatment of developmental and acquired structural disorders of the labia and vulva, such as labial hypertrophy and clitoral hood scarring/clitoral entrapment, will be discussed.

The diagnosis, classification, management, and surgical treatments of all female reproductive tract anomalies have changed with improvements in diagnostic imaging techniques, surgical and nonsurgical techniques and instrumentation, and the rapidly expanding field of reproductive medicine and assisted reproductive technologies. Long-term follow-up of the differing structural anomalies will be presented in relation to body image, patient satisfaction, and sexual and reproductive function.

Normal Developmental Embryology of the Reproductive Tract

The development of the female genital tract begins at 3 weeks of embryogenesis and continues into the second trimester of pregnancy. During the first 3 months of embryonic life, the primordia of both the male and the female reproductive tracts are present and develop together. Gonadal development results from the migration of primordial germ cells to the genital ridge (see Chapter 3), whereas the genital tract itself results from the formation and reshaping of the müllerian ducts (paramesonephric ducts), urogenital sinus, and vaginal plate.

The cell layers involved in the formation of the female reproductive tract are the mesoderm, the endoderm, and the ectoderm.

The mesoderm is divided into (a) paraxial mesoderm, which breaks up into segmental blocks (somites), forming the sclerotome (spinal cord, bone), dermatome (dermis), and myotome (musculature); (b) the intermediate mesoderm, which connects the paraxial and lateral plate as it differentiates into nephrogenic cord, forming the three kidney systems (pronephros [degenerates], mesonephros [only the wolffian system remains], metanephros [develops into the true kidney]); and (c) the lateral plate, which forms mesothelial or serous membranes of the peritoneal and pericardial cavities. In the peritoneum, the mesoderm provides primordium for the müllerian system and gonads. A defect or insult at any given somite or its contiguous mesoderm may give rise to congenital defects of multiple systems, such as the kidneys, the gonads, and corresponding ducts.

The endoderm is the epithelial lining of the primitive gut, the intraembryonic portions of the allantois and vitelline duct, respiratory tract, tympanic cavity and eustachian tube, tonsils, thyroid, parathyroid, thymus, liver, pancreas, urinary bladder, and urethra. The urogenital sinus forms the urinary bladder, allantois, and the prostatic, membranous, and penile urethra in males. It forms the urethra and vestibule in females. Both the prostate in males and the urethral/paraurethral glands in females are outbuddings of the urethra.

The ectoderm forms the central nervous system, the peripheral nervous system, and the sensory epithelium of sense organs. Of note, the fusion of endoderm and ectoderm contributes to patency (opening) and canalization, and defects result in fusion failures or imperforate/obstruction defects.

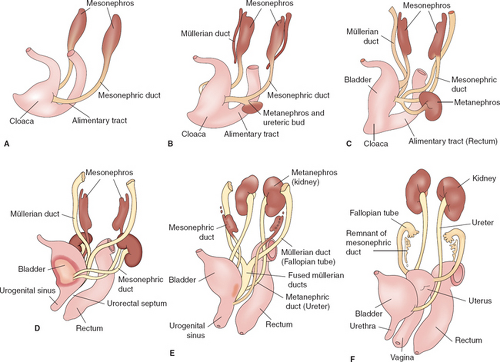

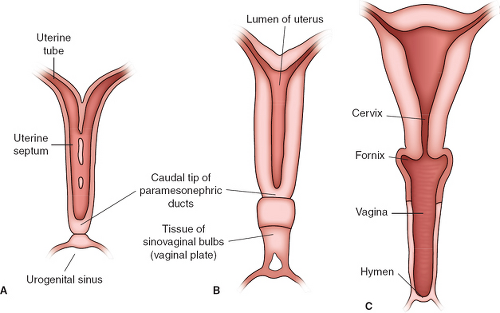

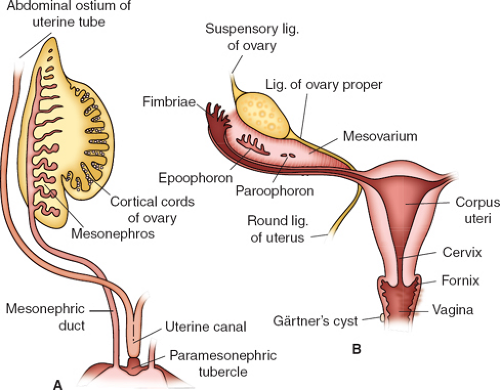

During the “indifferent” stage of development, two pairs of genital ducts develop in both sexes: the mesonephric ducts and the paramesonephric ducts. Paired mesonephric or wolffian ducts connect the mesonephric kidney to the cloaca (Fig. 12-1A). The ureteric bud arises from the mesonephric duct at approximately the fifth week and induces differentiation of the metanephros, which later becomes the functional kidney; the mesonephric kidney degenerates at 10 weeks (Fig. 12-1B). The müllerian (paramesonephric) ducts are first identified in embryos of both sexes at the 10-mm stage (sixth week) by the thickening of the anterior lateral coelomic epithelium covering the wolffian body; a slight groove lined with distinct epithelial cells is present, and a tube is subsequently formed by fusion of the lips of the groove. The elongating müllerian ducts lie lateral to the wolffian ducts until they reach the caudal end of the mesonephros, at which point they direct medially to nearly touch in the midline near the cloaca (Fig. 12-1C). The urorectal septum forms by the seventh week to separate the rectum from the urogenital sinus (Fig. 12-1D). By the 30-mm stage (ninth week), the müllerian ducts progress caudally and reach the urogenital sinus to form the uterovaginal canal, which inserts into the urogenital sinus at the Müller tubercle (Figs. 12-1E, 12-2A, and 12-3A).

By the 48-mm stage (12th week), the two ducts have completely fused into a single tube, the primitive uterovaginal canal, and two solid evaginations grow from the distal aspects of the müllerian tubercle: the sinovaginal bulbs (Figs. 12-1F and 12-2B). The sinovaginal bulbs are of urogenital sinus origin. Proximal to the sinovaginal bulbs, outgrowths from the müllerian ducts at the Müller tubercle result in the formation of the vaginal plate (Figs. 12-1F and 12-2B). The first and second portions of the müllerian ducts eventually form the fallopian tubes (Figs. 12-1F and 12-3B), while the distal segment forms the uterus and the upper vagina (Figs. 12-2C and 12-3B). It has recently been suggested through our observations that the fimbriae may be derived from nonmüllerian structures since they are present in cases of müllerian agenesis and have been theorized to play a role in the development of ovarian cancer (1).

By the 48-mm stage (12th week), the two ducts have completely fused into a single tube, the primitive uterovaginal canal, and two solid evaginations grow from the distal aspects of the müllerian tubercle: the sinovaginal bulbs (Figs. 12-1F and 12-2B). The sinovaginal bulbs are of urogenital sinus origin. Proximal to the sinovaginal bulbs, outgrowths from the müllerian ducts at the Müller tubercle result in the formation of the vaginal plate (Figs. 12-1F and 12-2B). The first and second portions of the müllerian ducts eventually form the fallopian tubes (Figs. 12-1F and 12-3B), while the distal segment forms the uterus and the upper vagina (Figs. 12-2C and 12-3B). It has recently been suggested through our observations that the fimbriae may be derived from nonmüllerian structures since they are present in cases of müllerian agenesis and have been theorized to play a role in the development of ovarian cancer (1).

It is the growth of the vaginal plate in conjunction with the sinovaginal bulbs that results in the restructuring of the urogenital sinus from a long, narrow tube to a broad, flat vestibule. These changes result in the positioning of the female urethra down to the future perineum. Canalization of the vaginal plate begins caudally and continues in a cephalad direction, creating the lower vagina (Fig. 12-2B, C). Canalization is complete by the fifth month of gestation. The distalmost portions of the sinovaginal bulbs proliferate to form the hymenal tissue (Fig. 12-2C). The hymen becomes perforate before birth.

The embryology should always “make sense” when determining anatomy and congenital anomalies of the reproductive tract. As a pediatric gynecologist, I have seen only one anomaly in the past 20 years where the physical findings contradicted established theories of embryology. This case involved a 14-year-old

with bilateral obstructed uteri that did not communicate with the normal vagina and midline single cervix. Since the uteri, cervix, and upper vagina are believed to be of müllerian origin, one would anticipate that the upper vagina and cervix would be contiguous müllerian tissue with the uterine structures (2). In general, if the anatomic findings are not consistent with basic principles of embryology, then most likely the diagnosis is not correct.

with bilateral obstructed uteri that did not communicate with the normal vagina and midline single cervix. Since the uteri, cervix, and upper vagina are believed to be of müllerian origin, one would anticipate that the upper vagina and cervix would be contiguous müllerian tissue with the uterine structures (2). In general, if the anatomic findings are not consistent with basic principles of embryology, then most likely the diagnosis is not correct.

Abnormalities of the Female Reproductive Tract

External Genitalia

Ambiguous Genitalia

The diagnosis, evaluation, and medical management of disorders of sex development (DSD) and specifically ambiguous

genitalia are presented in Chapter 3. The surgical management of these conditions is presented here by diagnosis.

genitalia are presented in Chapter 3. The surgical management of these conditions is presented here by diagnosis.

46,XX Disorder of Sex Development (Formerly Female Pseudohermaphrodites/Adrenogenital Syndromes)

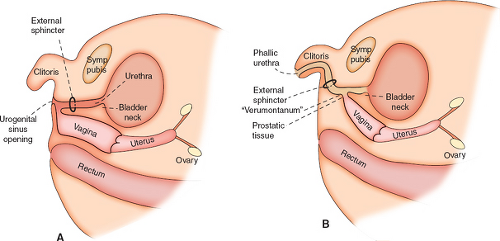

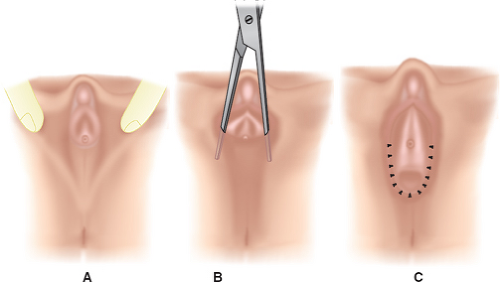

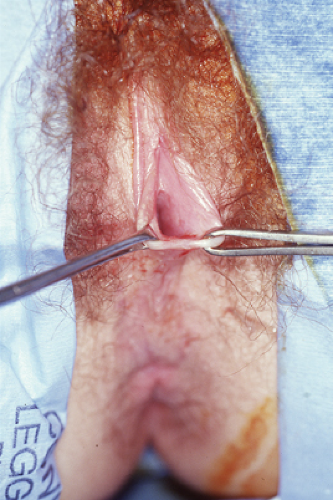

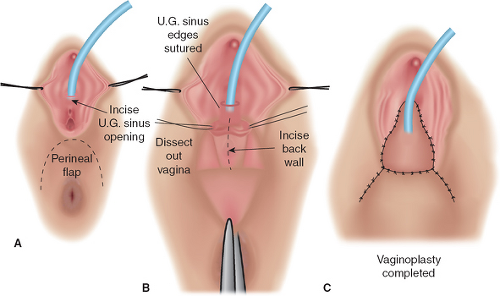

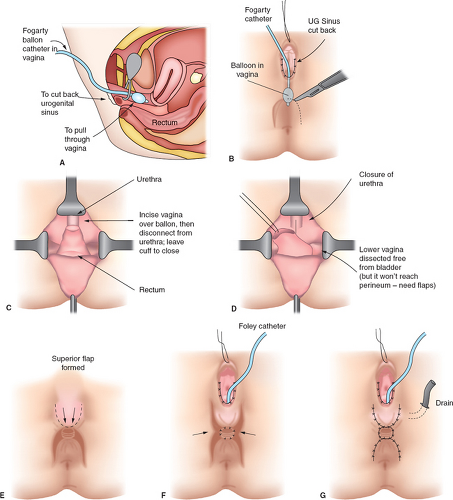

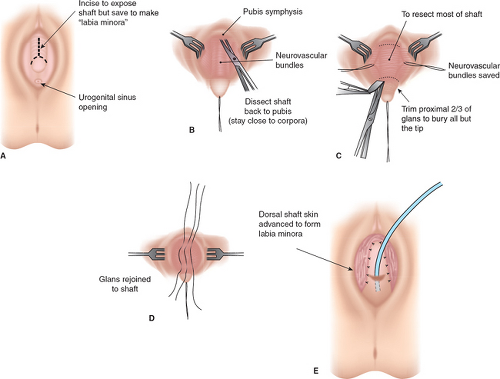

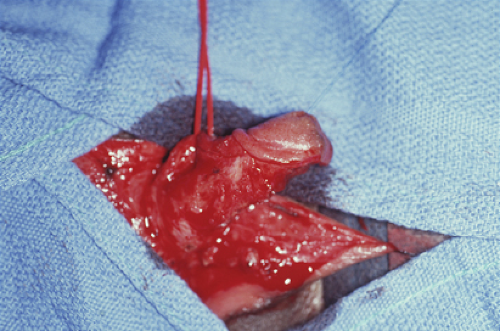

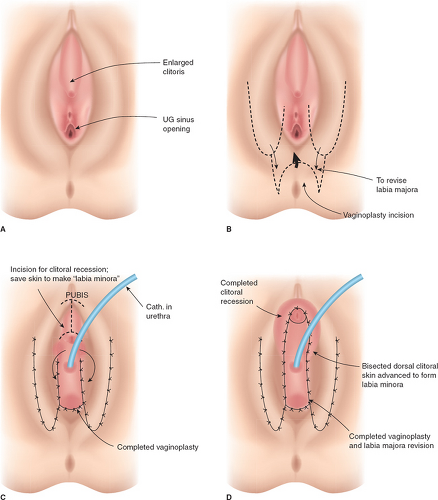

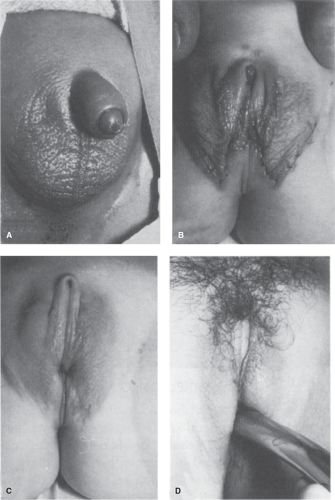

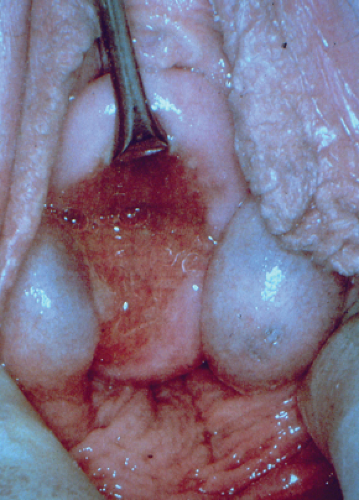

It should be emphasized that 46,XX DSD individuals (formerly female pseudohermaphrodites) are females with ovaries and are potentially fertile. Thus, regardless of the appearance of the external genitalia, the sex assignment has classically been female, but there is controversy in the appropriate management of these individuals today (see Determining Sex Assignment in Chapter 3). The majority of these individuals have masculinized external genitalia from congenital adrenal hyperplasia (CAH), but this can also result from maternal ingestion of exogenous androgens or from a maternal androgen-producing tumor. The type and extent of surgery depend on the degree of masculinization and the defined anatomy (3,4,5,6,7). In addition to the variations in the external genitalia, there are variations in the degree of masculinization of the lower urinary tract. Thick midline fusion with a single orifice may be appreciated with a urogenital sinus into which the vagina and urethra open separately, termed a low vagina (see Figs. 12-4A and 12-6 to 12-8), or the vagina can enter the urethra high between the external urethral sphincter and the bladder neck, termed a high vagina (see Fig. 12-4B) (8). For a low vagina, a cutback (see Figs. 12-5 to 12-9) or flap (see Fig. 12-10) vaginoplasty will create an adequate vaginal introitus. In cases of a high vagina, a pull-through procedure is necessary (see Fig. 12-11). Clitoral recession is usually accompanied by partial corporectomy, preserving the neurovascular bundle, and reanastomosis and preservation of the glans (see Figs. 12-12 and 12-13).

Historically, surgeons (pediatric general surgeons, urologists, and gynecologists) have performed the entire procedure (clitoroplasty, labioplasty, and vaginoplasty) in one, or at the most two, operations at 6 to 12 months of life (see Figs. 12-14 and 12-15). This technique usually requires an additional operation for revision of the vagina due to vaginal stenosis during adolescence (9). Alternatively, clitoroplasty can be performed at a young age and then a flap vaginoplasty and labioplasty delayed until later in adolescence (see Figs. 12-16 to 12-18). The labioscrotal tissue is advanced inferiorly so that the labia are positioned in appropriate proximity to the vaginal orifice;

a monsplasty can also be performed to create a normal “flat” mons as opposed to the grooved indentation seen in Fig. 12-16. There is evidence that girls undergoing vaginoplasty in adolescence report a higher level of satisfaction (10,11), whereas those undergoing vaginoplasty early in life have a low rate of compliance with dilators and less satisfaction with the long-term outcome (9,12). In addition, waiting to perform the vaginoplasty until during adolescence will avoid the need for parents to insert vaginal dilators in the postoperative child, which can be emotionally challenging to the child and parent. Many pediatric surgeons, pediatric urologists, and gynecologists support the concept that it is best to recess the phallus in childhood and wait until adolescence for the creation of a functional vagina when the young woman can direct the timeline and be compliant with the needed utilization of vaginal dilators (13).

a monsplasty can also be performed to create a normal “flat” mons as opposed to the grooved indentation seen in Fig. 12-16. There is evidence that girls undergoing vaginoplasty in adolescence report a higher level of satisfaction (10,11), whereas those undergoing vaginoplasty early in life have a low rate of compliance with dilators and less satisfaction with the long-term outcome (9,12). In addition, waiting to perform the vaginoplasty until during adolescence will avoid the need for parents to insert vaginal dilators in the postoperative child, which can be emotionally challenging to the child and parent. Many pediatric surgeons, pediatric urologists, and gynecologists support the concept that it is best to recess the phallus in childhood and wait until adolescence for the creation of a functional vagina when the young woman can direct the timeline and be compliant with the needed utilization of vaginal dilators (13).

Classically the goals of sex assignment and reconstructive surgical procedures have been based on the patient’s potential to achieve an unambiguous appearance to the external genitalia and achieve normal sexual function. A discussion of the determination of sex assignment is addressed in Chapter 3. As also discussed in Chapter 3, debate regarding the appropriate timing of “sex assignment” has gained additional attention by adult individuals with genital abnormalities. The Intersex Society of North America provides information and detailed options for patients and their families at www.isna.org.

46,XY Disorder of Sex Development (Androgen Abnormality/Insensitivity)

Androgen abnormality/insensitivity, a form of 46,XY DSD, formerly called male pseudohermaphroditism, may result from a wide variety of syndromes as addressed in Chapter 3 (11,12,14,15). With complete androgen insensitivity (CAIS) (previously referred to as testicular feminization), the individual has normal breast development but has pale areolae, absent or very sparse pubic and axillary hair, a

short vaginal pouch, and absence of the uterus and cervix (see Chapters 3 and 9). The gonads may be intra-abdominal or in the inguinal rings; the serum testosterone level is in the range of the normal male. Because of insensitivity to androgens and enhanced estrogen production, the patient develops a normal female habitus and external genitalia. These patients have elevated levels of antimüllerian hormone, also called müllerian inhibitory substance (MIS), during the first year of life; normal values from age 1 to puberty; and elevated levels again after pubertal development begins (16).

short vaginal pouch, and absence of the uterus and cervix (see Chapters 3 and 9). The gonads may be intra-abdominal or in the inguinal rings; the serum testosterone level is in the range of the normal male. Because of insensitivity to androgens and enhanced estrogen production, the patient develops a normal female habitus and external genitalia. These patients have elevated levels of antimüllerian hormone, also called müllerian inhibitory substance (MIS), during the first year of life; normal values from age 1 to puberty; and elevated levels again after pubertal development begins (16).

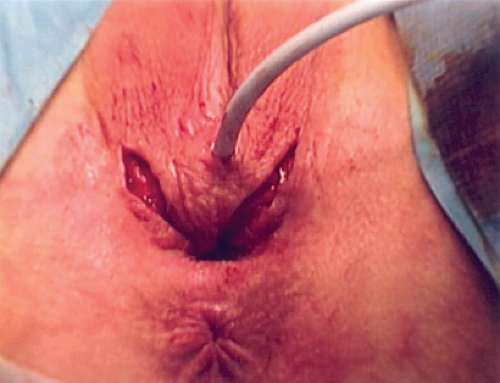

Figure 12-9. Suture closure of the low urogenital sinus seen in Figs. 12-6 to 12-8. |

Because the gonads in such patients have an increased risk (2% to 3%) of malignant degeneration with formation of dysgerminoma, consideration should be given to removal of the gonads prophylactically after the patient has completed pubertal development and attained full height and breast development (17,18) (see Chapter 21). The risk of malignancy increases from 3.6% at age 25 to 33% by age 50 (19). Rarely, children have had malignant degeneration of 46,XY gonads during childhood; therefore, it is suggested that patients in whom the diagnosis is made before puberty be monitored with ultrasound imaging to assess for the development of a pelvic mass (see Chapter 21) (20,21). Breast development is usually better in patients who have their gonads in place during adolescent development than in those who have undergone gonadectomy in childhood. The gonads can be removed by a laparoscopic technique (see Chapter 21). After gonadectomy, the patient should receive estrogen replacement. Some families may elect to hold off on gonadal removal until the young woman is over age 18 so that she can make the decision for herself as an adult (22,23). If this option is considered, then it is very important to make sure that the patient doesn’t have a nonhormonally functional dysgenetic gonad with Y-chromosomal material as this has a higher rate of malignancy (25% to 30%); in this case, early gonadectomy is recommended (17)

Before surgery is undertaken, the patient needs to understand her anatomy. The physician should stress the patient’s femininity and her ability to have normal sexual relations; she must, however, ultimately accept the fact that she cannot have menses or bear children. Relating the patient’s condition to genes or chromosomes can be helpful. Because of the openness of medical records to patients and families, the patient deserves a careful explanation about genetic patterns and assurance that although most people think that an XY individual is a male, in fact, there are women with this genetic pattern because of changes at the level of the DNA. The health care provider needs to answer questions honestly and at the same time emphasize that the patient’s phenotype is that of a normal female. The necessary surgery can be explained as removal of gonads, rather than testes; gonads can be viewed as organs that did not develop into either testes or ovaries because of the chromosomal problem. The risk of tumor should be openly discussed. Patients with androgen insensitivity syndromes usually have a blind vaginal pouch that, if needed, can be elongated with the use of vaginal dilators as described later (see Vaginal Agenesis below). A multidisciplinary approach with involvement of a mental health provider is helpful, as studies have shown that individuals with intersex disorders have a high rate of dissatisfaction regarding physical and psychological health (24).

Partial or incomplete androgen insensitivity has also been reported but is less frequent than complete androgen insensitivity (see Chapter 3) (12,13). A typical reported patient may have a 46,XY karyotype, labial fusion, a blind vas deferens, and testes located in the labioscrotal folds. At puberty, the patient develops breasts and pubic and axillary hair. Because of the absence of the uterus (due to the fact that production of MIS occurs normally), the patient usually seeks medical care for the evaluation of primary amenorrhea (see Fig. 9-1). Gonadal removal should not be delayed in adolescents with incomplete androgen insensitivity because of the potential for further virilization once the diagnosis has been made. In one series of 11 patients with incomplete androgen insensitivity, of whom five were prepubertal, eight showed evidence of germ cell neoplasia (see Chapter 21) (20).

Patients with androgen abnormality/insensitivity syndromes or other gonadal abnormalities may present with ambiguous genitalia or infantile male genitalia. If it is determined that these individuals should be reared as female (see Chapter 3), then feminizing genital reconstruction will need to be

performed (5,25). An inadequate phallus for urination in a standing position and sexual function has historically been the basis for the decision to proceed with feminizing reconstruction. The feminizing genitoplasty procedure is performed with the goals of maintaining clitoral sensation, clitoral recession to decrease the length of the clitoral shaft, creation of a properly positioned clitoral hood, mobilization of the labia in appropriate proximity to the vaginal orifice, and creation of an adequate vagina (size, location, and consistency). The surgery should result in the girl’s ability to void in a seated position and to have a normal-appearing vulva (5,25). Clitoral recession, relocation of the labia with labioplasty and vaginoplasty in an adolescent, is demonstrated in Figs. 12-13 and 12-15 to 12-18.

performed (5,25). An inadequate phallus for urination in a standing position and sexual function has historically been the basis for the decision to proceed with feminizing reconstruction. The feminizing genitoplasty procedure is performed with the goals of maintaining clitoral sensation, clitoral recession to decrease the length of the clitoral shaft, creation of a properly positioned clitoral hood, mobilization of the labia in appropriate proximity to the vaginal orifice, and creation of an adequate vagina (size, location, and consistency). The surgery should result in the girl’s ability to void in a seated position and to have a normal-appearing vulva (5,25). Clitoral recession, relocation of the labia with labioplasty and vaginoplasty in an adolescent, is demonstrated in Figs. 12-13 and 12-15 to 12-18.

Labial Hypertrophy

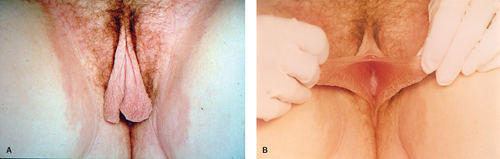

Enlargement of one or both labia minora (Fig. 12-19A, B) can result in irritation, chronic infection, and pain or can interfere with sexual activity or activity involving vulvar compression, such as horseback riding (26,27,28,29). In addition, the hypertrophy may result in psychosocial distress. Nonsymptomatic patients should be reassured that asymmetry or hypertrophy is not a

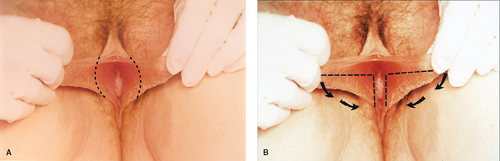

serious developmental abnormality. Symptomatic labial hypertrophy can be addressed with counseling about hygiene and the avoidance of tight clothes; these measures are usually sufficient to relieve the discomfort. If symptoms persist, or if the appearance is troublesome to the young woman, then a surgical procedure for labioplasty can be recommended. The labioplasty can be accomplished by resection of the hypertrophic excess labial tissue and the creation of symmetrically reduced labia (Fig. 12-20A); we have reported an alternative technique of wedge resection and reanastomosis in an attempt to decrease the exposed scar and improve outcome (Fig. 12-20B) (11,30,31). With both procedures there is a risk of superinfection and suture line breakdown. This risk appears to be increased with the wedge technique and thus our first-line therapy is the simple resection. During the recovery period, ice is helpful to reduce swelling, and frequent baths can help reduce suture breakdown by keeping the area clear and dry. Protection of the vulvar area during the postoperative healing period of the wedge technique can be aided by a plastic athletic support cup worn inside the patient’s underwear; this allows for normal activity without the risk of friction from the thighs against the suture area (30).

serious developmental abnormality. Symptomatic labial hypertrophy can be addressed with counseling about hygiene and the avoidance of tight clothes; these measures are usually sufficient to relieve the discomfort. If symptoms persist, or if the appearance is troublesome to the young woman, then a surgical procedure for labioplasty can be recommended. The labioplasty can be accomplished by resection of the hypertrophic excess labial tissue and the creation of symmetrically reduced labia (Fig. 12-20A); we have reported an alternative technique of wedge resection and reanastomosis in an attempt to decrease the exposed scar and improve outcome (Fig. 12-20B) (11,30,31). With both procedures there is a risk of superinfection and suture line breakdown. This risk appears to be increased with the wedge technique and thus our first-line therapy is the simple resection. During the recovery period, ice is helpful to reduce swelling, and frequent baths can help reduce suture breakdown by keeping the area clear and dry. Protection of the vulvar area during the postoperative healing period of the wedge technique can be aided by a plastic athletic support cup worn inside the patient’s underwear; this allows for normal activity without the risk of friction from the thighs against the suture area (30).

Disorders of Mesonephric Remnants

Persistent wolffian duct derivatives are commonly found in normal females (32,33). These remnants can result in pain or pelvic masses as follows:

A hydatid of Morgagni cyst is a cyst that is associated with the fallopian tube (see Chapter 21). It can be seen in Fig. 21-1. The presence of these cysts may increase the risk of tubal and

ovarian torsion. These cysts can be removed laparoscopically; the fallopian tube can be salvaged and not compromised.

ovarian torsion. These cysts can be removed laparoscopically; the fallopian tube can be salvaged and not compromised.

Cysts of the broad ligament can result in large simple cystic pelvic masses (Fig. 21-2). Patients may present with pain and/or abdominal distention, or the cysts may be identified on routine examination. The management of these cysts is discussed in Chapter 21.

The Gärtner canal (duct) may retain a ureteral connection and form an ectopic ureter, which may communicate with the perineum. In addition, remnants of Gärtner ducts can result in cystic formations of the cervix or vaginal walls (see Fig. 12-21). These embryologic remnants do not need to be resected unless they cause pain or interfere with sexual activity or the use of tampons.

Introital Abnormalities

Masses

Introital masses are common in the neonate and young child and include developmental and nondevelopmental abnormalities (see Chapters 1, 4, and 15). The differential diagnosis includes urethral prolapse (see Figs. 4-7 and 15-9), ectopic ureter, prolapsed ureterocele (see Fig. 4-9), hymenal skin tag (see Fig. 1-17), rhabdomyosarcoma (see Fig. 4-11), condyloma (see Fig. 4-2), paraurethral cyst (see Fig. 4-8), vaginal cyst (see Fig. 15-12), obstructed hemivagina (Fig. 12-22A), or imperforate hymen (see Figs. 1-10, 1-14, 4-10, and 15-11). The patient should be examined in order to determine the origin of the mass. In a neonate or child, the “pull-down” traction maneuver for visualizing the introitus should be utilized (see Fig. 1-6) to visualize the entire vestibule and distal vagina.

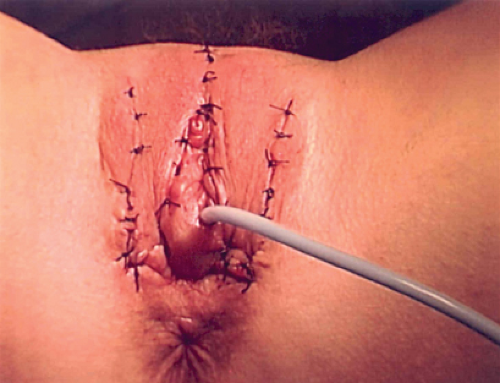

Figure 12-17. Patient in Fig. 12-16 with incision for posterior flap vaginoplasty. |

Figure 12-18. Patient in Figs. 12-16 and 12-17 status post posterior flap vaginoplasty, monsplasty, creation of a clitoral hood, and inferior mobilization of the labia. |

Bartholin Duct/Gland Cyst/Abscess

In the adolescent, the above-mentioned abnormalities may exist, and in addition Bartholin duct cysts or abscesses may occur (see Chapter 18). Bartholin duct cysts do not need to be drained or removed unless the patient is symptomatic. If the Bartholin duct becomes infected and an abscess forms, it may need to be drained when it is “pointing.” A Word catheter should be placed to maintain a drainage tract. If the abscess recurs, a marsupialization or resection procedure should be considered (see Chapter 18). Resection of the gland is reserved for recurrent abscesses with failed marsupialization procedures due to the risk of profuse bleeding at the time of surgery and subsequent scar tissue formation and dyspareunia.

Ectopic Ureter

An ectopic ureter (see Chapter 15) that communicates with the perineum can cause chronic vaginal irritation, vulvar/vaginal “wetness,” or pain (see Chapter 4) (34). Ultrasound may be utilized to assist in the diagnosis, and an intravenous pyelogram is confirmatory. According to the Weigert-Meyer rule, the ectopic ureter communicates with the upper pole of the duplex kidney; the greater the distance of the ectopic location from the orthotopic ureteral orifice, the more dysplastic is the upper pole of the duplex kidney (35). A pediatric urologist should be consulted for corrective surgery to appropriately ligate/implant the ectopic ureter and/or to perform an upper pole nephrectomy (see Chapter 15).

It should be noted that there have been at least five cases of clear cell cancer of the vagina in adolescent women who have had an ectopic ureter into the vagina from a dysplastic kidney (36,37). Since the incidence of this association is unclear, there is no standard recognized and widely accepted protocol for surveillance. We promote every-other-year examination under anesthesia and Papanicolaou (Pap) tests for children and biyearly vaginal examinations and yearly vaginal Pap tests in adolescents with this condition.

Prolapsed Ureterocele

When the duplex collecting system has a ureter that ends in a ureterocele, the ectopic ureter with ureterocele also arises from the upper collecting system in the duplex kidney. The ureterocele may present as an introital mass if it prolapses through the urethra (see Fig. 4-7 and Chapter 15). The prolapsed ureterocele is managed by marsupialization of the obstructed end to relieve the obstruction, and then the nonobstructed duplex ureter prolapse is reduced into the bladder; additional urologic procedures of the ectopic ureter, bladder, or upper pole of the kidney may be required (38,39).

Introital Cysts

Hymenal, periurethral, and vaginal cysts are usually of the epidermal inclusion variety. Most of these cysts will resolve spontaneously within 3 months. Even if the cyst does not resolve it is usually asymptomatic and can be left in place. If the cyst does not resolve and is symptomatic, then the cyst can be marsupialized or resected. Prior to surgical intervention, a transperineal ultrasound is helpful to confirm the diagnosis. In addition, cystoscopy should be performed at the time of the surgery to rule out a urethral diverticulum.

Hymenal Skin Tags/Masses

Hymenal skin tags (see Fig. 1-17) are common findings. They usually regress, but if a lesion is symptomatic with inflammation, superinfection, or bleeding, it can be excised in order to relieve the symptoms. Larger hymenal masses may be fibroepithelial polyps (Fig. 12-23) and should be removed. The risk of a malignancy in hymenal masses is rare, but sarcoma botryoides can occur in this area; if there is any doubt as to the etiology of a mass it should be excised (see Chapter 4).

Congenital Hymenal Abnormalities

Congenital variations of the hymen are demonstrated in Fig. 1-10. An adolescent’s abnormal hymen that results in a small orifice should be corrected surgically if she is unable to use tampons, insert vaginal cream or suppositories, or have vaginal intercourse. The cribriform, septate, or microperforate hymen can be revised with resection of the “excess” hymenal tissue to create a functional hymenal ring. It should be noted that there have been reports of familial occurrence of hymenal abnormalities, and thus women should be aware that their daughters may have a similar abnormality. Patient handouts addressing abnormal hymenal abnormalities are available at http://www.youngwomenshealth.org/hymen.html.

Subsymphyseal Epispadias

Subsymphyseal epispadias is a rare urologic condition (see Chapter 15) that can be seen in Fig. 12-24. The vagina and upper reproductive tract are normal although the hymen may be septate, as seen in this image.

Bladder Exstrophy

Exstrophy of the urinary bladder is an uncommon anomaly that requires timed reconstruction in a series of stages (see Chapter 15). The anal orifice is usually close to the vagina. Years after repair, adolescents may complain of introital stenosis or of the structural abnormality of the mons and/or clitoris. The upper reproductive tract is usually normal. Individuals with this condition have a bifid clitoris (Fig. 12-25). It is not uncommon for women with a history of bladder exstrophy to develop cervical/uterine prolapse. Surgery can alleviate the prolapse and its associated symptoms of pain, irritation, vaginal discharge/bleeding, or difficulty with sexual activity. The repair usually requires a monsplasty, a Williams vulvovaginoplasty, and a Manchester-Fothergill procedure in a one-stage operation (40). The result is usually excellent, and patients have full sexual and reproductive function. Pregnancy can occur without complication; delivery can be achieved by either a vaginal or an abdominal route (41).

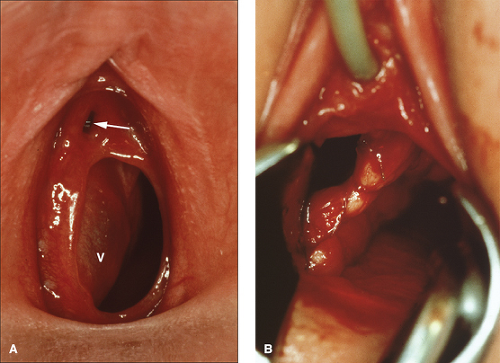

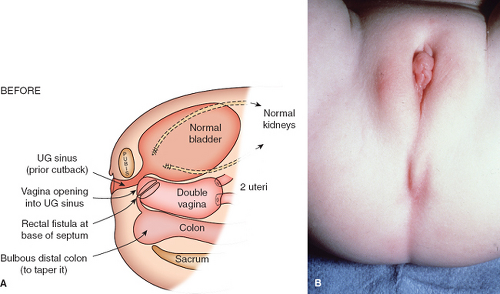

Cloacal Anomalies

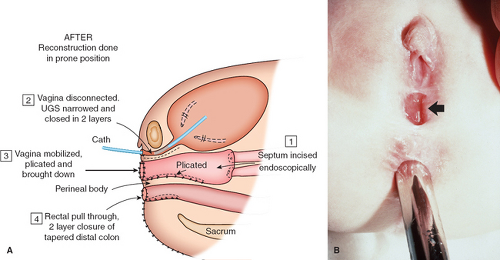

A cloaca is a common canal involving the gastrointestinal, urinary, and genital tracts. The word cloaca means “sewer” in Latin. A wide range of anatomic variation can occur with the interruption of the normal differentiation of these three organ systems (42,43). The abnormality usually results in a failure of the normal fusion of the müllerian ducts with subsequent duplication of the uterus and proximal vagina (Fig. 12-26A). The sinovaginal bulbs do not form, and the vaginal plate does not develop normally. The urogenital sinus persists, and the urethra enters high on the anterior wall; the hymen and lower vagina do not form appropriately. The examination reveals a “blank” perineum (Fig. 12-26B). Before corrective surgery is performed, the patient needs to have the existing anatomy clearly defined with radiologic and endoscopic evaluations (42,44). According to W. Hardy Hendren’s reports of extensive experience with over 195 patients, surgical repair for a primary cloaca is usually done when the patient is between the ages of 9 and 18 months (42,45). Surgical construction for individuals with a cloacal abnormality is performed by a pediatric surgeon or by a team consisting of a pediatric surgeon, a pediatric urologist, and a pediatric gynecologist. Through extensive procedures, separate functional urinary, gastrointestinal, and reproductive tracts are created (Fig. 12-27A). As shown in Fig. 12-27B, there is a perineal body between the new anus and the pull-through vagina. The new urethra lies just beneath the somewhat enlarged clitoris. When the patient is older, the labial tissue can be moved more posteriorly to surround the vaginal opening, as demonstrated in Figs. 12-16 to 12-18 (8,42,43). Multiple revisions of the surgery may be required to create a satisfactory result for all affected functional systems. Full sexual and reproductive function is possible for genetic female individuals with the cloacal anomaly; pregnancy has been reported with both abdominal and vaginal deliveries (42,46). Discordant sexual identity has been reported in some genetic males with cloacal exstrophy assigned to female sex at birth (47).

Anomalies of the Uterus, Cervix, and Vagina

In general, anomalies of the female reproductive tract result from abnormalities of agenesis/hypoplasia, vertical fusion (canalization abnormalities resulting from abnormal contact with the urogenital sinus), lateral fusion (duplication), or resorption (septum). Each of these abnormalities is associated with specific symptoms, physical findings, evaluation, and therapy. Uterine and vaginal malformations may be identified by the clinician when a patient experiences primary amenorrhea, acute and/or chronic pelvic pain, abnormal vaginal bleeding, or a foul-smelling vaginal discharge (often worse at the time of menses), or incidentally on physical examination. Patients with anomalies that result in obstruction of a functional reproductive tract usually have complaints that differ from those without an obstructive anomaly. Combined uterine and vaginal obstructions may be difficult to diagnose and treat. Although rare, these entities are challenging and are frequently missed in the early adolescent years because the pelvic pain, irregular,

or vaginal discharge may be attributed to functional disturbances. Ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), laparoscopy, examination with the patient under anesthesia, and/or intraoperative hysterosalpingograms may be useful in defining the anatomy in these patients so that the appropriate management options can be presented and reconstruction, if needed, can be performed. Obstructive anomalies may require immediate surgical or medical intervention to address the obstruction, whereas nonobstructive anomalies do not require surgical intervention unless the patient has reached

reproductive age and has been shown to be adversely affected by the anomaly.

or vaginal discharge may be attributed to functional disturbances. Ultrasonography, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), laparoscopy, examination with the patient under anesthesia, and/or intraoperative hysterosalpingograms may be useful in defining the anatomy in these patients so that the appropriate management options can be presented and reconstruction, if needed, can be performed. Obstructive anomalies may require immediate surgical or medical intervention to address the obstruction, whereas nonobstructive anomalies do not require surgical intervention unless the patient has reached

reproductive age and has been shown to be adversely affected by the anomaly.

Figure 12-27. A: Cloacal anomaly after reconstruction. B: Three months after reconstruction of patient in Fig. 12-26 with arrow at constructed vaginal orifice, and a dilator in the anorectal canal. UGS, urogenital sinus. (From Hendren WH. Urogenital sinus and cloacal malformations. Semin Pediatr Surg 1996;5:72; with permission.) |

Classification Systems

The basic classification of anomalies of the müllerian tract includes agenesis/hypoplasia, vertical fusion (canalization) defects, and lateral fusion (duplication) defects. The American Society for Reproductive Medicine (ASRM) (formerly the American Fertility Society [AFS]) has adopted a classification system of müllerian anomalies, which is shown in Table 12-1 (48,49).

The ASRM system is based on the degree of failure of normal development and separates the anomalies into groups with similar clinical manifestations and prognoses for fetal salvage upon treatment. These different subtypes of anomalies based on reproductive function were proposed to allow for long-term studies of the reproductive outcomes of each type of anomaly in order to provide better information for health care providers who counsel affected individuals.

Table 12-1 Classification of Müllerian Anomalies According to the ASRM Classification System | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||

Table 12-2 Vaginal Classification | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||

The ASRM classification system does not include vaginal anomalies but allows for the inclusion of a description of associated vaginal, tubal, or urinary anomalies. Others have suggested classification systems for vaginal anomalies as demonstrated in Table 12-2 (50,51).

Revisions to the ASRM classification have been proposed (52). The VCUAM (Vagina Cervix Uterus Adnexa-associated Malformation) Classification as shown in Table 12-3 was proposed in 2005 and intended to focus on the anomalies not addressed in the ASRM system (53,54). Revisions/new classification systems have still been proposed since limitations of classification still exist (55).

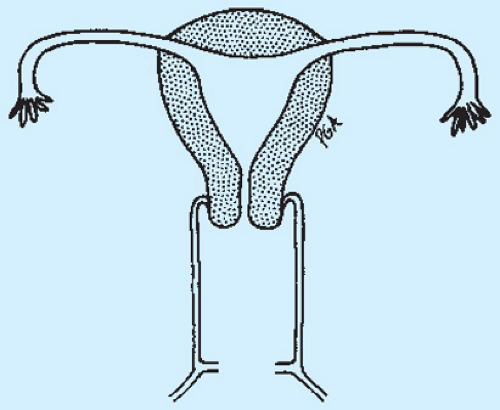

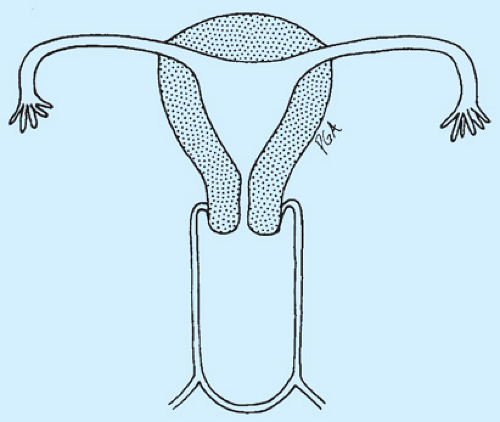

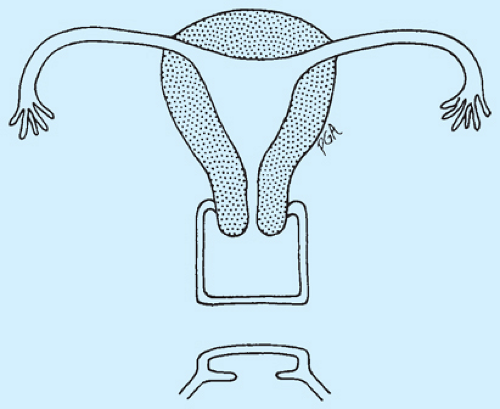

Figure 12-28 shows a schematic drawing of a normal reproductive tract, and Figs. 12-29 to 12-65 demonstrate schematic diagrams of variations of defects of the female genital tract that include and demonstrate uterine, cervical, tubal, vaginal, and renal abnormalities.

Genetics

The etiology of anatomic defects of the female genital tract is not fully understood. Most forms of isolated müllerian duct

and urogenital sinus malformations are inherited in a polygenic/multifactorial fashion. Mendelian forms of inheritance with a single gene mutation have been described to explain the McKusick-Kaufman syndrome (MKS), and the hand–foot–genital syndrome involves the HOXA13 gene (56). It should be noted that we have recently reported a set of monochorionic/monoamniotic twins where one twin has Mayer-von Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome and one does not (57). Table 12-4 lists syndromes associated with vaginal anom-alies, Table 12-5 lists syndromes associated with longitudinal vaginal septum, and Table 12-6 lists syndromes associated with müllerian anomalies.

and urogenital sinus malformations are inherited in a polygenic/multifactorial fashion. Mendelian forms of inheritance with a single gene mutation have been described to explain the McKusick-Kaufman syndrome (MKS), and the hand–foot–genital syndrome involves the HOXA13 gene (56). It should be noted that we have recently reported a set of monochorionic/monoamniotic twins where one twin has Mayer-von Rokitansky-Küster-Hauser (MRKH) syndrome and one does not (57). Table 12-4 lists syndromes associated with vaginal anom-alies, Table 12-5 lists syndromes associated with longitudinal vaginal septum, and Table 12-6 lists syndromes associated with müllerian anomalies.

Table 12-3 VCUAM Classification | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Incidence

The true incidence of müllerian duct anomalies is not known. Different reports have described a wide range of incidence,

depending on whether a general population is evaluated at the time of obstetric delivery or one with a history of infertility or habitual miscarriage (58,59,60,61). In a study of fertile women who were evaluated for müllerian duct anomalies at the time of tubal ligation, an incidence of 3.2% was identified (60). Many women may have an underlying asymptomatic müllerian duct anomaly; since they have no pain, pelvic mass, infertility, or reproductive compromise, they may not come to diagnosis. Because familial occurrences of anomalies of the female reproductive tract have been reported, families should be screened by history for the possibility that female relatives have also been affected (62).

depending on whether a general population is evaluated at the time of obstetric delivery or one with a history of infertility or habitual miscarriage (58,59,60,61). In a study of fertile women who were evaluated for müllerian duct anomalies at the time of tubal ligation, an incidence of 3.2% was identified (60). Many women may have an underlying asymptomatic müllerian duct anomaly; since they have no pain, pelvic mass, infertility, or reproductive compromise, they may not come to diagnosis. Because familial occurrences of anomalies of the female reproductive tract have been reported, families should be screened by history for the possibility that female relatives have also been affected (62).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree