Strabismus

Robert W. Enzenauer, Mary Ellen Hoehn, and Monte A. Del Monte

Strabismus is the term used to describe any ocular misalignment. The term originates from the Greek strabismus, meaning to “look askance” or the “evil eye.” Ocular misalignment that is constantly present and not controlled by fusional mechanisms is termed a tropia. A phoria is defined as a latent deviation that is controlled by fusional mechanisms and only present when one eye is blocked or covered. An intermittent tropia is a deviation that may sometimes be latent and controlled by fusional mechanisms (ie, a phoria) but may at other times be spontaneously manifest, often with illness or fatigue. Most children with strabismus develop a deviation that manifests mostly in one eye (the nondominant eye). Some strabismic children are able to switch fixation, using one eye at times and the other eye at other times, so that the strabismus will appear to shift from one eye to the other. This is termed alternating strabismus. In some children, strabismus develops as a result of poor vision in one eye and is termed sensory strabismus. Strabismus may also be the presenting sign of a life-threatening disease (eg, brain tumors with cranial nerve palsy) or vision-threatening conditions such as retinoblastoma or cataract.

Strabismus affects between 1% and 4% of children. The two most common types of strabismus are esotropia (cross-eyes, convergent squint, inwardly turned eyes) and exotropia (walleyes, divergent squint, outwardly turned eyes). Strabismus has been shown to occur in families and is noted more frequently among those children who have other neurological or medical conditions, including those affected by prematurity, low birth weight, cerebral palsy, intrauterine infection or drug exposure, craniofacial abnormalities, Down syndrome, and other genetic disorders.

Amblyopia develops in as many as 50% of children with strabismus.1 Early diagnosis and treatment of strabismus is therefore crucial to developing optimal, binocular visual function. Brief periods of intermittent esotropia or exotropia may be commonly observed during the first 2 to 3 months of life. This does not require referral to an ophthalmologist. However, any ocular misalignment after 3 months of age should be referred to an ophthalmologist for further evaluation. Likewise, any large or constant deviation should never be considered normal.

In addition to defining strabismus by the direction of the misalignment, it can also be categorized by the consistency of the amount of misalignment in different positions of gaze. A comitant strabismus is one in which the ocular misalignment is the same magnitude (measured by the ophthalmologist in units called prism diopters) in primary (straight-ahead gaze), left, right, up, and down gaze. All of the esotropias and exotropias discussed below are comitant. When one or more muscle(s) is paretic or restricted, the amount of strabismus will differ depending on the position of gaze. This is called an incomitant strabismus. Although nearly every paretic vertical strabismus (most commonly a superior oblique [cranial nerve IV] palsy) starts out incomitant (different in different gazes), it often becomes comitant over time. When strabismus is incomitant, the patient may adopt an anomalous head position to put the eyes in a position of gaze where they are most aligned while looking straight ahead. If patching of one eye eliminates the anomalous head position, an ocular cause is likely responsible and referral to an ophthalmologist is indicated.

There are many potential benefits to correcting strabismus.2 Strabismus surgery is reconstructive rather than cosmetic. Restoration or development of binocular vision can improve fusion, stereoacuity, and binocular visual field and can restore normal visual function in both eyes. This can lead to long-term stability of ocular alignment and help to reduce the number of eye surgeries required throughout a patient’s lifetime. A normal ocular alignment also enhances social interaction and eye contact, while uncorrected strabismus can adversely affect employability.3

DETECTION OF STRABISMUS

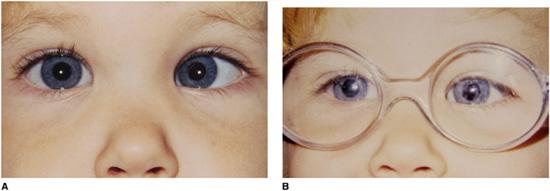

The pediatrician’s main tool in recognizing the presence of strabismus is the corneal light reflex (Hirschberg test). In normal individuals, a light shone directly or indirectly into the eyes will appear as a white reflex located centrally (or just nasal to center) in each pupil. If the eyes are misaligned, then the reflex appears at a different position relative to the pupil in the deviated eye. In esotropia (Fig. 586-1), the reflex appears more laterally in the pupil compared to the straight eye, which is fixating on the light or examiner. In exotropia (see below), the light reflex appears more nasal relative to the pupil in the deviated eye. In hyper/hypotropia, the light reflex is displaced vertically (see below).

Figure 586-1. Infantile esotropia. Note position of Hirschberg light reflex, which is more lateral relative to the pupil in both eyes. More commonly, one eye would be straight and the other largely esotropic.

ESOTROPIA

PRIMARY INFANTILE ESOTROPIA

PRIMARY INFANTILE ESOTROPIA

Primary infantile esotropia develops in the first few weeks to months of life, most often prior to 6 months of age. Previously, this condition had been incorrectly termed congenital esotropia. There is often a family history of strabismus, with esotropia observed in as many as 10% to 20% of first-degree relatives.4 Classic infantile esotropia is constant and involves a large amount of misalignment, often 25 to 35 degrees (40 to 60 prism diopters) at both distance and near viewing (Fig. 586-1). Infantile esotropia rarely can resolve spontaneously over time, with the magnitude of deviation being inversely proportional to the probability of resolution. Multiple studies have confirmed that a constant large esotropia that is still present at age 2 to 4 months is unlikely to resolve without treatment, and the angle of strabismus may increase with continued observation.5

Normal amounts of farsightedness are present in most of these patients. Glasses are therefore not generally required or helpful, as the esotropia is unrelated to the refractive error. Significant nearsighted or astigmatic refractive error, if present, may require correction, not to improve the alignment but to maximize vision. Managing primary infantile esotropia generally involves eye muscle surgery, which is successful approximately 80% of the time after a single operation. Surgical treatment of infantile esotropia generally involves recession (weakening) of the medial rectus muscles on both eyes. Most clinical experience suggests that very useful, sometimes near-normal sensory and oculomotor functions can be developed or restored if successful ocular alignment is achieved within the first 2 years of life.6,7 The optimum timing for eye muscle surgery for primary infantile esotropia is the subject of much research, with some suggesting intervention as young as 6 months of age in an effort to maximize binocular visual potential. Even surgery as early as 13 weeks has been advocated by some ophthalmologists.8 Botulinum toxin injection into the medial rectus has been investigated as an alternative to traditional surgery. While some authors have noted success with smaller deviations, the efficacy when compared to incisional surgery has not always been convincing.9

Careful longitudinal follow-up of these patients is necessary, since an accommodative esotropia (see below) requiring glasses can develop at a later date. Even with successful surgical ocular realignment, patients with infantile esotropia are more likely to exhibit latent nystagmus, vertical misalignment, and monocular smooth pursuit abnormalities. These features may persist throughout the patient’s life.

ACCOMMODATIVE ESOTROPIA

ACCOMMODATIVE ESOTROPIA

When we focus on objects near us, the ciliary muscle of the eye contracts, resulting in relaxation of the lens (a process called accommodation), and the eyes converge. Children have particularly large abilities to accommodate. We lose this ability in later adulthood and thus the reason for needing reading glasses or bifocals. If a child is farsighted, they need to accommodate even more than usual to focus, and they are able to do so without any sense of stress or discomfort. In fact, most children are farsighted in the first decade of life, and very few need glasses. But in some children, this excess accommodative need results in overconvergence of the eyes, called accommodative esotropia.

Children with accommodative esotropia generally present between the ages of 18 and 48 months of age, with an average age of onset of 2.5 years. The esotropia is often intermittent in the beginning and becomes constant without intervention. The amount of esotropia is generally less than is present in patients with primary infantile esotropia and may be more prominent at near fixation. These children have larger than average amounts of hyperopia, averaging about +4 diopters, with some patients exhibiting as much as +8 to 10 diopters. Over 30% of children with +4 diopters or more of hyperopia will develop esotropia by 3 years of age. Amblyopia may also develop, even bilaterally, in children whose hyperopia is excessively high. Some experts contend that children with accommodative esotropia more frequently have amblyopia at presentation than children with infantile esotropia.

Figure 586-2. Accommodative esotropia. Child has left esotropia (note abnormal Hirschberg light reflex) with glasses off (A) but straight eyes with glasses on (B).

Managing accommodative esotropia usually involves spectacle correction for the farsightedness to eliminate the need to accommodate and overconverge. Bifocals may be required if there is excessive accommodative convergence at near fixation. With the glasses on, the patient has straight eyes. When the glasses are removed, the patient again starts to accommodate in order to see clearly and the eyes are esotropic (Fig. 586-2). The child may actually see as clearly without the glasses as with them, but the glasses are there to keep the eyes straight.

A second form of accommodative esotropia does not involve farsightedness. Children with this subtype of esotropia often have straight eyes, or nearly so, when looking at an object in the distance, but their eyes cross excessively only when fixating on near objects. This is due to an abnormal relationship between accommodation and convergence. These children are most often treated with reading glasses (if correction is needed only for near work) or bifocals (if they also need correction to see clearly at a distance, such as with astigmatism).

A miotic agent such as phospholine iodide, a cholinesterase inhibitor, is sometimes effective in realigning the eyes of patients with accommodative esotropia where compliance with wearing glasses is poor but potential ocular and systemic side effects limit their long-term usage.

It is normal for children to demonstrate increasing amounts of hyperopia until 6 to 8 years of age, when the amount of hyperopia naturally begins to decrease in most children. In patients with accommodative esotropia, a gradual reduction (“weaning”) of the spectacle strength may be possible over time, while maintaining good vision and alignment. If glasses are worn faithfully and good fusional patterns are established, many patients with refractive esotropia can be weaned from their glasses by the time they are teenagers. The same is true for bifocals. When beneficial, bifocal correction can often be weakened after 4 to 7 years of age and even eventually eliminated in over half of cases, usually by the midteens. A few eye surgeons recommend eye muscle surgery for children who cannot be weaned out of bifocals by 15 to 16 years of age. This allows the patient to discontinue bifocal wear and simply wear single-vision glasses or contact lenses.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree