Sleep History and Differential Diagnosis

Developing a Differential Diagnosis: Process of Solving Clinical Problems

Hypotheses form the basis of inquiry into patients’ presenting problems. They are generated very early in the assessment, and they are then refined by completing the clinical history and by performing a physical examination. The set of hypotheses is then further refined into an actual diagnosis or a list of possible (differential) diagnoses.1 Laboratory testing may be needed when the history and physical examination alone do not lead to a final diagnosis.

Evaluation of the Clinical History

In one study of 202 children who presented consecutively to a developmental and behavioral pediatric practice, parents and other primary caretakers were found to only infrequently report that the child under their care had a sleep problem, even when symptoms suggesting a sleep disorder were present.2 Simply asking the parent the single question, ‘Does your child have a sleep problem?’ is inadequate to determine the presence or absence of problematic sleep.

A sleep history obtained from a frustrated, sleepy parent can be vague and inaccurate, with the parent focusing, at times, on the wrong details. For example, parents often describe the child’s sleep pattern only for the most severe or most recent night or period. A more accurate depiction of the sleep patterns across time can be obtained from a sleep diary, log, or chart. For this reason, the parent can be asked to maintain a sleep chart or log for a period of 2 to 4 weeks prior to the first visit (and then again during treatment). This item then becomes very helpful in identifying habitual sleep–wake cycle patterns and provides documentation of abnormalities occurring from night to night.2 Maintaining a sleep log seems to improve observational skills of the child’s caretaker, increases validity of observational data, and can be indirectly therapeutic. Parents might see on paper what actually happened most nights. Sleep disorder professionals might find review of such documents useful to clarify the actual pattern of what is happening and such review might well be the most accurate way of documenting progress.

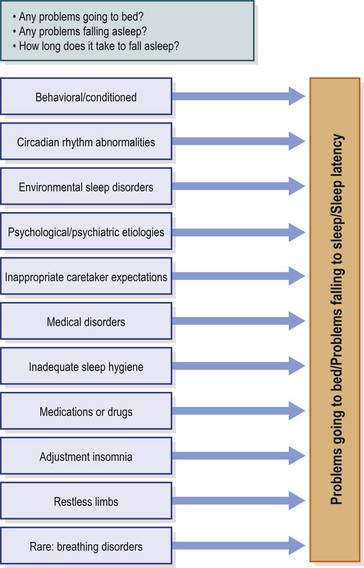

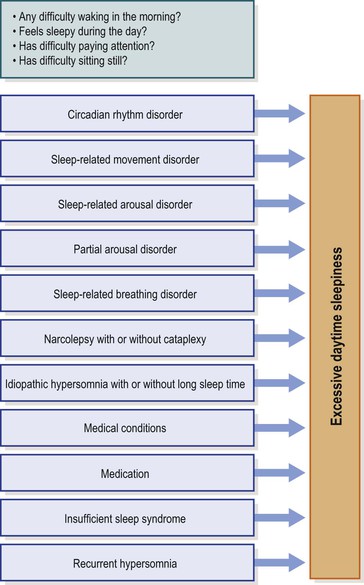

It is important to begin with a screening process that might provide insight or cues to the practitioner that a problem requiring further consideration might be present. A structured approach to screening the history has been tested and validated.3 An important first step is obtaining information regarding the typical/habitual sleep patterns and difficulties. A number of screening tools have been developed to assist the child health care practitioner in assessing for sleep-related disorders and have been comprehensively reviewed by Spruyt and Gozal.4 These authors, however, conclude that very few of these tools fulfill all the necessary properties required, and only a few are standardized. None of the tools had any diagnostic power in and of itself – thus, making the diagnosis remains in the domain of the clinician. One questionnaire, the BEARS Screening Tool developed by Owens and Dalzell, had particular usefulness in the primary care setting as well as in the sleep medicine center.5 It has questions regarding Bedtime, Excessive daytime sleepiness, Awakenings at night, Regularity/duration, and Snoring, the answers to which suggest a series of possible diagnoses (see Figures 9-1 to 9-5).

Figure 9-1 Bedtime.

Adapted from: Owens JA, Dalzell V. Use of the ‘BEARS’ sleep screening tool in a pediatric residents’ continuity clinic: a pilot study. Sleep Medicine 2005:6:63–69. With permission.

Figure 9-2 Excessive daytime sleepiness.

Adapted from: Owens JA, Dalzell V. Use of the ‘BEARS’ sleep screening tool in a pediatric residents’ continuity clinic: a pilot study. Sleep Medicine 2005: 6: 63–69. With permission.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree