Sleep and Its Disturbances in Autism Spectrum Disorder

Introduction

Epidemiological studies in children with ASD now lend support to the suggestion that their sleep difficulties start at a very young age and tend to persist.1,2 Even when children with learning difficulties and medical comorbidities are excluded, an excess of sleep problems are still found in children with ASD.2

Given that the causes of ASD themselves are poorly understood, it comes as no surprise that the origins of sleep disorders in ASD are still unclear. Despite efforts by diagnostic systems to classify ASD as a single entity, the evidence is to the contrary. Indeed, the symptoms of ASD cluster in dimensions rather than into clear categories, and such an interpretation is likely to provide an easier framework for exploring some of the associated sleep problems.3

Epidemiology

In general, solid epidemiological studies of sleep patterns, sleep behaviors, and sleep quality in patients with ASD are lacking. Studies have been small, lacked controls, and have often used non-validated diagnostic tools.4

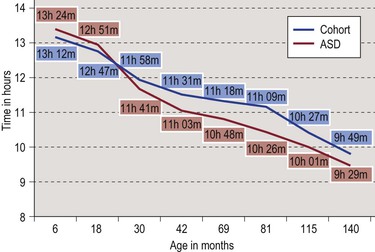

Evidence from one of the longitudinal protocols comes from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children (ALSPAC), a prospective study of a cohort of over 14 000 children born in 1991–2 in southwest England.5 Parental reports of sleep duration were collected by questionnaires at eight time points from 6 months to 11 years, including from 86 children with an ASD diagnosis (determined at age 11 from health and education records).1 Children with ASD slept for 15 to 45 minutes less each day compared to contemporary controls aged 30 months to 11 years old (Figure 16-1). The difference remained significant after adjusting for gender, epilepsy, high parity, and ethnicity. The difference in sleep duration mostly reflected changes in nighttime rather than daytime sleep duration. Nighttime sleep duration was shortened because of both later bedtimes and earlier waking times. Frequent wakings, defined as three or more times a night, were significantly more common in children with ASD from 30 months of age.

Figure 16-1 Total mean sleep duration in ASD children compared to total cohort. Adapted from Humphreys J et al.1

Another population-based cohort study assessed sleep problems at two age ranges (7–9 and 11–13 years).2 A screening questionnaire was used to define autism spectrum problems and, in this group, the prevalence of chronic insomnia was more than ten times that seen in controls; and, in the ASD children, the sleep problems were more persistent over time.

Evidence from a cross-sectional study comes from a study of children between 4 and 10 years of age randomly selected from a regional autism center.4 This descriptive cross-sectional study compared both subjective and objective measures of sleep in an ASD cohort with those of typically developing (TD) controls. In this study more than half of the families of the children with ASD (57.6%) voiced concerns about sleep problems, including the presence of long sleep latencies despite a bedtime routine, frequent night wakings, sleep terrors, and early risings. Only 12.5% of families of the TD cohort reported sleep concerns. Objective actigraphy measurements showed children with ASD took longer to fall asleep, were more active during the night, and had the longest nighttime duration of a wake episode. However, sleep efficiency, total sleep time, and the number of long wake episodes, as determined by actigraphy, were not statistically different between the ASD and TD cohorts.

Sleep Profiles and Sleep Architecture

Wiggs and Stores6 used sleep questionnaires, parental diaries, and actigraphy to describe the profile of sleep disturbance in children with ASD. They found that the sleep disorders underlying the sleeplessness were most commonly behavioral, although sleep–wake cycle disorders and anxiety-related problems were also seen. They did not find that sleep patterns measured with actigraphy differed between those ASD children with or without reported sleeplessness. Similar findings were reported in studies by Malow et al.7 and Souders et al.4 They used International Classification of Sleep Disorders-2 (ICSD-2)8 nomenclature and found the commonest sleep diagnoses were behavioral insomnia of childhood – sleep-onset type and insomnia due to PDD.

Sleep Architecture and Dreaming in ASD

A small controlled study found that young adults with ASD have fewer recollections of dreaming than controls.9 Their dream content narratives following REM sleep awakenings were shorter with fewer social and emotional experiences. Spectral analysis of the same group showed distinctive slower alpha EEG patterns and asymmetries in the ASD group.10

Objective support for REM differences is still in the early stages and is inconsistent. A recent controlled single-night PSG study found rapid eye movement (REM) sleep percentage was lower in children with ASD compared with both children with typical development and children with other developmental disorders.11 Although interesting, the numbers of children were small and some of the differences found might relate to differences in mean age of the different groups of children. Additionally, a first night effect might account for part of this finding and, in fact, one two-night study did find that REM sleep percentage was lower on night 1 but not night 2.12

If REM differences in ASD are real, the potential implications are intriguing. REM sleep is greatest in the developing brain and may represent a protected time for neuroplasticity.13 REM sleep is involved in memory consolidation and, according to several studies, normal cognitive function and processing of emotional memory.14,15 In the autism research field where rat and mouse models of autism are being developed, it has been shown that REM deprivation in the neonatal rat induces social deficiencies in the adult animal.16 The hypothesis elaborated most recently by Buckley et al.11 goes so far as to suggest that ‘a primary cholinergic deficiency may simultaneously produce deficits in REM sleep in autism and contribute to the socio-emotional deficits at the core of the autistic phenotype …’ There is enough belief in this hypothesis to support a recent open-label study, discussed later in this chapter,17 designed to pharmacologically increase REM percentage in children.

Causes of Sleep Problems in Children with ASD

Learning Difficulty

Children with ASD may present with varied language and cognitive phenotypes. Young people with high-functioning autism and Asperger’s syndrome might have average or above-average cognitive abilities, in contrast to non-verbal children with profound learning difficulties. This level of cognitive impairment, although normally a strong predictor for sleep problems, seems less so in ASD where children across a wide range of cognitive abilities have been reported as having sleep problems at an equally high rate. It is tempting to speculate that, although sleep problems in general may be equally common among these groups, the specific nature of these problems is group-dependent. A high rate of anxiety in many of the young people with Asperger’s syndrome is often encountered that exacerbates bedtime insomnia18 with perseverative rituals that further increase sleep latency.19

Sensory Issues

Hypersensitivities are well described in people with ASD.20 Parents attest to the challenges of trimming nails, cutting hair, and even getting their children to wear clothes. The environmental nuances occurring at bedtime, with demands or needs around room and bed (e.g., special sheets, particular sounds, favorite pajamas) are often marked and problematic for families of children with ASD. The theory underlying the reasons for using weighted blankets and other weighted items for calming purposes on these youngsters is based on the idea of sensory integration, a concept initially developed by the occupational therapist Jean Ayres21 and further developed by occupational therapists and other professionals.22 It has been hypothesized that the deep pressure provided by weighted items provides proprioceptive input to the body resulting in an inhibitory response that reduces the body’s physiological level of arousal and stress.23 The safety and efficacy of this intervention is not known although a large controlled study in the UK is underway (L. Wiggs and P. Gringras, personal communication).

Genes, Neurobiological Factors, and Melatonin

Although there have been many attempts to use putative genetic and biochemical findings from ASD studies to explain the sleep difficulties seen in children with ASD,24 these attempts suffer from two fundamental problems: first, there is no evidence that ASD exists as a single disorder with a single cause, and second, the actual causal pathways that lead to ASD are poorly understood.

Although ASD was once thought to be caused by environmental factors, genetic factors are now considered to be more contributory to its pathogenesis. These include, for example, mutations in certain clock-related genes and in other genes that encode synaptic molecules associated with neuronal communication.25 However, epigenetic mechanisms are also likely to be important; and, these mechanisms are affected by environmental factors (such as nutrition, drugs and mental stress), and they control gene expression without changing DNA sequence.26 For a more complete review of autism neurobiology, the reader is directed to a comprehensive summary by Silver and Rapin.27

Perhaps the greatest efforts have centered on the hormone melatonin because of its known importance in sleep neurobiology and relevance also to ASD research. Abnormal platelet serotonin level remains one of the few consistent biochemical findings in children with autism.28 Serotonin is a biochemical precursor to melatonin, and there has been considerable research into the components of this pathway. Genetic abnormalities have been reported in the two melatonin receptors,29 and a variety of mutations have been described in acetylserotonin-o-methyltransferase (ASMT), one of the enzymes responsible for the synthesis of melatonin from serotonin.29,30 However, the overall numbers of children in these studies whose ASD and sleep problems were associated with these specific ASMT mutations are very small and the findings have not been replicated in all genetic studies.31

Although the genetic findings still only explain a few case findings, there is other evidence that melatonin physiology is important in ASD. In one study by Malow and colleagues, the level of a melatonin metabolite was directly related to the amount of deep sleep in children with ASD.32 The role of exogenous melatonin in treating the sleep of children with ASD is discussed later in the treatment section of this chapter.

Seizures

When a child (and particularly a very young child) presents initially with seizures, the focus of caretakers and clinicians is reducing the frequency and intensity of the seizures and investigating their causes. It is usually only later, when the seizures are under control, that a range of language, cognitive, social, behavioral, and sleep problems emerge or become recognized.33 About 30% of children with autism also have epilepsy,34 but it is still not known how often a shared underlying cause accounts for both disorders. However, seizures are often activated in sleep. So, when evaluating a child with autism who experiences unusual repetitive sleep-associated behaviors (or possible parasomnias), one should maintain a high index of suspicion of a possible underlying seizure disorder. Despite the technical challenges of studying these children (who may well be aversive to the investigations required), full EEG and polysomnography are often essential. For additional information on epilepsy and sleep, also see Chapter 44.

Co-morbidities in ASD

Unfortunately, much of the sleep and ASD research has sought to study pure groups of children with ASD. While this approach has certain advantages, it also reduces the generalizability to the real clinical situation where comorbidity of both medical and psychiatric conditions is the rule.35

When the prevalence of current comorbid DSM-IV disorders was carefully assessed in children and adolescents with ASD, 72% were diagnosed with at least one comorbid disorder.35 Anxiety disorders (41%) and ADHD (31%) were the most common, but higher rates of obsessive–compulsive disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and tic disorders were also present. Many of these disorders are themselves associated with sleep problems (see Chapters 15 and 46), and their frequency in children with ASD suggests they should not be ignored. Clinically, we have observed that there is often an additive effect, where the prolonged sleep latency and bedtime resistance commonly seen in children with ADHD36 is exacerbated in ASD by an additional degree of cognitive rigidity and by a lack of empathy regarding the sleep of other family members.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree