Sleep Disorders

Hemant Sawnani and Narong Simakajornboon

A survey from the National Sleep Foundation (NSF) shows that 69% of children under 10 years of age experience some type of sleep disturbance.1 Significant sleep problems affect 25% to 40% of children and adolescents.2 These sleep problems tend to persist to adulthood if left untreated. Despite the high prevalence of sleep problems, most pediatricians do not ask question about children’s sleep. The survey from community practice shows that pediatricians acknowledge the importance of sleep problems, but they fail to screen adequately for them, especially in older children and adolescents.3 Untreated sleep disorders can lead to long-term consequences. Several studies have demonstrated the association between sleep disorders and cardiovascular and neurocognitive complications. Therefore, it is crucial that pediatricians recognize the signs and symptoms of sleep disorders and integrate sleep issues as part of the routine health maintenance. In this chapter, normal sleep development and the common sleep problems encountered in general pediatric practices are discussed. Obstructive sleep apnea is reviewed in Chapter 508.

NORMAL SLEEP AND SLEEP MATURATION

Knowledge of sleep regulation, normal sleep, and its change during development is essential to understand and recognize sleep disorders in children and adolescents. Certain features of sleep help in the diagnosis of sleep disorders. For example, night terror, a phenomenon that occurs in nonrapid eye movement (NREM) sleep, is more likely to occur during the first part of the night when NREM predominates, while nightmares, a rapid eye movement (REM) phenomenon, are common during the latter part of the night. Sleep is the result of complex interaction between sleep- and wake-promoting neurons. The sleep-promoting neurons are located in the ventrolateral preoptic nucleus, which contains GABA-ergic (Gamma-amino-butyric acid) and galaninergic neurons. The awake-promoting neurons are located in the posterior lateral hypothalamus, which contains orexin/hypocretin neurons. A model is proposed in which wake-and sleep-promoting neurons inhibit each other, which results in stable wakefulness and sleep.4 Sleep and alertness are regulated by 2 important factors: the homeostatic factor, which depends on prior sleep duration and quality and awakening time and the circadian rhythm or intrinsic biological clock. These 2 forces interact and allow the diurnal pattern of sleep with consolidated sleep at night and wakefulness during daytime. Two “sleepiness” periods occur in humans. The first occurs at night between midnight and 6.00 am and the second in the early afternoon.5 The circadian rhythm is affected by several environmental cues (zeitgebers), such as social interaction and timing of meals, but the most important environmental cue is light exposure, which has different effects on the biological clock depending on the time of exposure.

Normal human sleep comprises 2 major stages, NREM and REM sleep, based on the characteristic of the electroencephalogram, electromyo-gram, and electrooculogram.6 NREM sleep is subdivided into 4 stages. Stage 1 is defined by an attenuation of high-frequency alpha wave (8–13 Hz); the presence of low-amplitude, mixed-frequency electroencephalogram (theta wave, 4–7 Hz); a slight decrease in chin electromyogram from awake; vertex sharp waves; and slow, rolling eye movements (eFig. 509.1  ). Stage 1 accounts for 3% to 8% of total sleep time. Stage 2 is characterized by the presence of sleep spindles (distinct waves with frequency 12–14 Hz) and K-complex (negative sharp wave followed by a positive component) (eFig. 509.2

). Stage 1 accounts for 3% to 8% of total sleep time. Stage 2 is characterized by the presence of sleep spindles (distinct waves with frequency 12–14 Hz) and K-complex (negative sharp wave followed by a positive component) (eFig. 509.2  ). Humans normally spend 45% to 55% of total sleep time in stage 2, and it is the most prevalent stage of sleep. Stages 3 and 4 are typified by increased slow-wave sleep (> 20% for stage 3 and > 50% for stage 4; eFigs. 509.3 and 509.4

). Humans normally spend 45% to 55% of total sleep time in stage 2, and it is the most prevalent stage of sleep. Stages 3 and 4 are typified by increased slow-wave sleep (> 20% for stage 3 and > 50% for stage 4; eFigs. 509.3 and 509.4  ). Stages 3 and 4 account for 15% to 20% of total sleep time. REM sleep is characterized by a significant decrease in chin electromyogram; the presence of low-amplitude, mixed-frequency electroencephalogram pattern; and the occurrence of rapid eye movement (eFig. 509.5

). Stages 3 and 4 account for 15% to 20% of total sleep time. REM sleep is characterized by a significant decrease in chin electromyogram; the presence of low-amplitude, mixed-frequency electroencephalogram pattern; and the occurrence of rapid eye movement (eFig. 509.5  ). Stage REM accounts for 20% to 25% of total sleep time.

). Stage REM accounts for 20% to 25% of total sleep time.

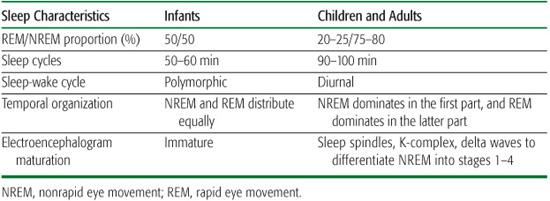

Sleep pattern and sleep architecture undergo developmental changes from infancy to adolescence. Sleep in infants has several features that are different from children and adults (Table 509-1). Active or REM sleep is approximately 50% and is the dominant state of sleep. Quiet or NREM sleep accounts for only 35% to 45% of total sleep time. REM sleep in premature infants can be as high as 80% of total sleep time. The percentage of REM sleep decreases with increasing age and reaches an adult proportion by 5 to 6 years of age. The sleep cycle (the total duration of NREM and REM in 1 cycle) of infants is 50 to 60 minutes, while that of adults is 90 to 100 minutes. In infants, NREM and REM sleep distribute equally throughout the night. In contrast, in older children and adults, NREM sleep predominates in the first part of the night, while REM sleep predominates in the latter part of the night. Another distinct feature of infant sleep is that the entry of sleep is through REM sleep, while that of children and adults is through NREM sleep. Normal full-term neonates spend most of their time sleeping (16–18 h/day).7 Sleep pattern in infants is polymorphic with multiple naps during the day. Infants begin to consolidate their sleep by about 3 months. By age 12 months, infants will have a long nighttime sleep and 2 daytime naps. At age 18 months, the naps are decreased from 2 to 1. At age 5 years, 75% of children give up their naps, but social and cultural difference may influence this pattern. By age 6 years, children sleep approximately 10 to 11 hours, and the sleep need does not change until adolescence.

Table 509-1. Characteristic Differences between Infant’s and Children’s Sleep

Sleep in adolescents has unique features as a result of physiologic changes during puberty. The major change is a shift in melatonin secretion and circadian sleep phase, leading to phase delay with propensity to later onset of sleep and later wake-up time.8 In addition, social and academic demands during this period can predispose adolescents to sleep deprivation.9 Some adolescents cope with this problem by sleeping longer during the weekend, which can make the phase delay worse. Studies show that adolescents need 9 hours of sleep, and the sleep need in adolescents does not change across the adolescent span (10–17 years).8 However, most adolescents sleep only 7 to 7.5 hours each night, which results in significant sleep debt over time. Only 15% of adolescents sleep 8.5 or more hours on school nights, and 26% of high school students sleep 6.5 hours or less each school night.10 Adolescent also have irregular sleep patterns, which could contribute to shift in sleep phase. The average increase of weekend over weekday sleep is almost 2 hours per night.10 Sleep debts in adolescents can lead to significant long-term consequences, including daytime sleepiness and changes in mood, attention, memory, behavior, and academic performance.

Table 509-2. Criteria for Diagnosing Definite Restless Legs Syndrome in Children

1. The child meets all 4 essential adult criteria for RLS (the urge to move the legs, is worse during rest, is relieved by movement, and is worse during the evening and at night); and |

2. The child relates a description in his or her own words that is consistent with leg discomfort (the child may use terms such as oowies, tickle, spiders, boo-boos, want to run, and a lot of energy in my legs to describe the symptoms (age-appropriate descriptors are encouraged). |

Or |

The child meets all 4 essential adult criteria for RLS, and 2 of the 3 following supportive criteria are present: |

1. Sleep disturbance for age. |

2. A biologic parent or sibling has definite RLS. |

3. The child has a polysomnographically documented periodic limb movement index of 5 or more per hour of sleep. |

RLS, restless legs syndrome.

COMMON SLEEP DISORDERS

RESTLESS LEGS SYNDROME AND PERIODIC LIMB MOVEMENT DISORDERS

RESTLESS LEGS SYNDROME AND PERIODIC LIMB MOVEMENT DISORDERS

Periodic limb movement in sleep is characterized by periodic episodes of repetitive and highly stereotypic limb movements.11 Periodic limb movement disorder (PLMD) is defined by the presence of periodic limb movements during sleep associated with symptoms of insomnia or excessive daytime sleepiness.11 Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a clinical diagnosis characterized by disagreeable leg sensations that usually occur prior to sleep onset. RLS and PLMD are common in adults, with a prevalence of 4% to 10%.12 The prevalence in children has not been well studied, although approximately 30% to 40% of adult patients report the onset of RLS symptoms before the age of 20.13 One recent study reports the prevalence of RLS is 1.9% in children 8 to 11 years old and 2.0% in children 12 to 17 years old.14 The prevalence of RLS in boys and girls is similar,14 while the female-to-male ratio is 2:1 in adult RLS.15 Children with RLS and PLMD may present with nonspecific symptoms such as growing pains, restless sleep, and hyperactivity.16 These symptoms are often not noticed by parents, although a family history of RLS and PLMD is common.17 Several studies show the strong association between attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and RLS and PLMD. The relation is somewhat complex. It is estimated that 10% to 30% of children with ADHD may have RLS and PLMD.12,17 In addition, 44% of children with RLS have been found to have ADHD or ADHD symptoms.18 This association has many possible explanations.18 Sleep disruption associated with RLS and PLMD might lead to inattentiveness and hyperactivity; RLS and PLMD may be a comorbidity of ADHD; RLS and PLMD and a subset of ADHD may share a common dopa-mine abnormality; and diurnal manifestations of RLS and PLMD might mimic ADHD.

The etiology of RLS and PLMD is not known. Several studies show the role of genetics, dopamine dysfunction, and low iron stores in the pathophysiology of RLS and PLMD. A recent study shows the association between PLMD and a common variant in an intron of the protein BTBD9 on chromosome 6p21.2.19 Many children with RLS and PLMD have low iron storage, as evidenced by low serum ferritin and/or iron.20,21 Several conditions are associated with increased risk of RLS and PLMD (secondary RLS), including pregnancy, uremia, iron deficiency, and anemia.

The diagnosis of RLS and PLMD requires specific diagnostic criteria. The 4 classic, essential adult criteria for RLS include (1) the urge to move the legs, (2) worsening of the urge during rest, (3) relief by movement, and (4) worsening during the evening and at night.22 Children present a diagnostic challenge because of the inability to describe classic leg paresthesia. The international RLS study group has developed criteria for making a diagnosis of RLS and PLMD in children (Tables 509-2 and 509-3).12 In addition to essential adult criteria, children should be able to provide age-appropriate descriptions of leg discomfort, such as tickle, spiders, bugs, or energy in my legs. In children who are unable to describe their symptoms, other supportive criteria are needed, including sleep disturbance for age, a family history of RLS, and a polysomnographic finding of periodic limb movements in sleep (index of 5 or more per hour of sleep). For PLMD, the diagnosis requires a polysomnographic study to establish a minimum periodic limb movement index of 5 or more per hour. Periodic limb movements in sleep are characterized by a sequence of 4 or more limb movements with duration of 0.5 to 5 seconds and separated by an interval of more than 5 seconds and less than 90 seconds (Fig. 509-1). Sleep disturbance, including sleep onset and sleep maintenance problems and daytime sleepiness, is an important part of the diagnostic criteria of PLMD. Because sleep-related respiratory abnormalities such as obstructive sleep apnea and upper airway resistance syndrome can lead to arousals associated with limb movements, movements following respiratory events are excluded.23 Therefore, respiratory monitoring including nasal airflow and respiratory efforts are essential in making a diagnosis of PLMD.

Table 509-3. Criteria for Diagnosing Periodic Limb Movement Disorder in Children

1. Polysomnographic study shows a periodic limb movement index of 5 or more per hour; and |

2. Clinical sleep disturbance for age must be evident as manifested by sleep-onset problems, sleep-maintenance problems, or excessive daytime sleepiness; and |

3. The leg movements cannot be accounted for by sleep-disordered breathing or medication effect (antidepressant medication). |