Sleep and School Start Times

Introduction

Over the last three decades, an accumulation of studies have clearly demonstrated that delaying school start times works as an effective countermeasure to adolescents’ chronic insufficient sleep while also enhancing students’ health, safety, and academic success.1–5 Inadequate sleep is one of the most common, significant, and potentially reparable health challenges that adolescents struggle with over the middle through high school years. From a biological perspective, at about the time of puberty, the majority of adolescents begin to experience later sleep onset and offset times (i.e., a circadian phase delay).6–10 This shift can be as long as 2 hours in comparison to elementary schoolers’ sleep–wake schedules. For more than two decades, studies have demonstrated that three key changes in sleep regulation are probably responsible for this phenomenon: (1) adolescents experience a delay of the evening onset of melatonin secretion, expressed as a shift in circadian phase preference from lark to owl type, resulting in difficulty falling asleep at an earlier bedtime; (2) adolescents undergo a change in regulatory homeostatic ‘sleep drive’ whereby the accumulation of sleep propensity while awake slows relative to younger children, making it easier for them to stay up later; (3) adolescents’ sleep needs do not decline from pre-adolescent levels with optimal sleep amounts ranging from 8.5 to 9.5 hours per night.8,7,10–13 On a practical level, this means that the average adolescent has difficulty falling asleep before about 11 p.m., and is unlikely to wake up before 8 a.m. In addition to these three significant developmental changes, environmental and lifestyle factors interfere with adolescents getting sufficient and regular sleep. There is clear and compelling evidence that delaying middle and high school start times gives adolescents the opportunity to obtain an adequate amount of sleep with implications for academic performance and health. In the chapter that follows, we review over 30 years of research on adolescent sleep–wake patterns and the countermeasures and interventions where schools delayed their school start times.

Adolescents’ Sleep–Wake Needs and Patterns

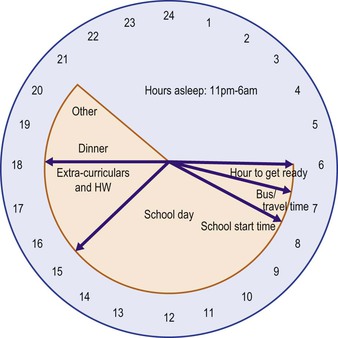

It is not surprising that adolescents often ignore their need for sleep to accommodate social, technology, academic, and escalating extracurricular demands.8,14–16 Teenagers’ ability to function throughout the school day, however, is influenced by the quantity, regularity, and quality of their sleep. As observed in many countries, self-reported sleep patterns show marked changes over the adolescent years.17–20 Beginning as early as sixth or seventh grade (approximately age 12), the majority of adolescents report increasingly later bedtimes, especially on weekend and vacation nights.20–23 School-night bedtimes range from 9:30 p.m. to midnight with high school-aged adolescents (ages 14–19 years), reporting significantly later bedtimes than their early adolescent peers (ages 10–13 years).3,24 Rise times on school days remain relatively stable across this developmental stage largely due to school schedules.3,7,22,24 Many schools in the USA, Great Britain, Canada, and elsewhere, however, start significantly earlier than 8 a.m., leading to wake times that range from about 6:00 a.m. to 7:00 a.m. (Figure 48-1).25–27

Figure 48-1 This clock represents a breakdown of how an adolescent may spend the 24 hours of his or her day. The orange pie shape represents the hours spent awake, while the blue signifies hours spent asleep, compared with the recommended 9.2 hours. The overlap shows the difference in hours of sleep lost when school start time is earlier than recommended by research.

Due largely to early wake times and delayed bedtimes on school days, adolescents tend to report increasingly less sleep during the week over the middle and high school years. Time in bed ranges from as little as 5 to closer to 8 hours, with older adolescents reporting less time in bed than younger adolescents.3,24,28,29 In striking contrast to self-report studies, laboratory-based research reveals that older adolescents may need the same amount or even more sleep in comparison to their younger early adolescent peers.8,12,30,31

In Carskadon and colleagues’ landmark research, now known as the Stanford Sleep Camp study, pre- and early adolescents, ages 10 to 12, were assessed during three consecutive summers.31 Participants were given the opportunity to sleep for a maximum of 10 hours (10 p.m.–8 a.m.) while in the laboratory for three consecutive nights. Using polysomnographic (PSG) recordings, Carskadon and colleagues found that the amount of time spent asleep during these 10 hours remained constant across puberty stages (Tanner stages 1–5), and averaged 9.2 hours.31 In fact, if anything, it was the older and more mature adolescents who needed to be awakened after 10 hours, suggesting that they may have slept longer if given the opportunity.

Research suggests that many adolescents attempt to make up for insufficient school-night sleep by oversleeping on the weekend. Time in bed averages about 0.5 to 2.5 hours more on weekend compared to school nights, and this disparity increases from ages 14 to 18.3,24,32,33 Likewise, most adolescents typically delay going to sleep about 1 to 2 hours on weekends in comparison to school nights, and extend their sleep period by waking 1 to 4 hours later on weekends. Self-reported bedtimes characteristically range from about 10:30 p.m. to midnight or later on weekend nights, and weekend wake times typically range between 9 and 10 a.m. or later on weekend mornings, with older adolescents reporting later sleep–wake schedules than their younger siblings and friends.3,22,32,33

Developmental Changes to Sleep/Wake Regulatory Systems

The adolescent’s circadian system also undergoes significant developmental changes.11,34 In self-report, questionnaire-based studies, more advanced pubertal status is associated with owl-like preferences, and laboratory studies demonstrate that more mature adolescents experience later onset and offset melatonin secretion or what is referred to as a circadian phase delay.7,11,35 Sadeh and colleagues examined developmental sleep changes in relationship to the timing of the onset of puberty.36 Using actigraphy and self-reported pubertal status, they found that later sleep onset times and shortened sleep times emerge prior to the expression of secondary sexual characteristics associated with puberty.36 Alterations to the sleep–wake regulatory systems during puberty seem to allow mature adolescents to stay awake later at night to finish their favorite You-Tube or Netflix video or to text message a few more friends, while their younger and less mature peers are more likely to fall asleep more easily. As a result, it is more difficult for adolescents to fall asleep and awaken early compared to their elementary school or pre-adolescent-aged friends and siblings. Parents might experience this as the ‘sleep-over’ problem. In other words, it is easier for older adolescents to act like they can remain alert after a late night sleepover, whereas younger, middle school-aged adolescents cannot function following a sleepover. This pronounced sleep debt leads to school absenteeism and tardiness, daytime sleepiness, emotion regulation difficulties, and academic struggles.3,5,28,37 Moreover, adolescents perhaps compensating for sleep loss with increased caffeine and stimulant use or drug use and abuse.38–41 There is little doubt that adolescents are getting insufficient and inconsistent sleep, with clear negative implications for physical and emotional well-being, academic performance, and other daytime behaviors and activities.

Environmental constraints and lifestyle decisions including family socioeconomic status, substance use, after-school employment hours, and high-tech use further exacerbate and interfere with many adolescents’ ability to obtain sufficient sleep or to maintain a regular sleep–wake schedule.3,14,22,40,42–44 Undoubtedly, the biological delay in sleep onset and the social pressures of the teen years in combination with the need to arise early in the morning for school easily creates a situation in which the adolescent chronically obtains inadequate sleep. Extracurricular activities and technology use may be more or less under an adolescent’s control; however, the determination of high school and middle school start times is not in their hands.

Meeting Adolescents’ Sleep Needs: Delaying School Start Times

Minimal research exists to explain why high schools historically start earliest, followed by middle schools, and why elementary schools traditionally start the latest.25 High school start times across the United States have been informally and formally surveyed. One pilot study compared data over the period of 1975–1996 for 59 early-starting (before 8:00 a.m.) and late-starting (8:00 a.m. and later) high schools. Early-starting schools maintained their early schedules over the 20-year time period.45 A sampling of 1996–1997 school year schedules posted on the Internet from 40 high schools throughout the United States found that 48% had start times of 7:30 a.m. or earlier, with only 12% starting between 8:15 and 8:55 a.m.44 Another assessment of 50 high schools from around the country for the 2001–2002 school year found 35% of schools posted start times before 7:30 a.m. and 16% between 8:15 and 8:55 a.m.46 Ten years later, in a 2012 web-based sampling of 50 high schools’ school year bell schedules, 30% of the high schools still listed start times for before 7:30 a.m., with 10% of the high schools listing 8:15–9:00 a.m. as their 2012–2013 school start times. In comparison, a sampling of 50 middle schools’ 2012–2013 schedules revealed that 14% set start times for 7:30 a.m. or earlier, with 20% starting between 8:15 and 8:55 a.m. Previously, Wolfson and Carskadon conducted a comprehensive analysis of factors that contributed significantly to the determination of high school start times and whether these times changed across the decades.25 Over 4000 public high schools, representing 10% of public high schools in the United States, were randomly selected from the National Center for Education Statistics’ online database and asked to complete a brief survey regarding the pattern of school schedules and student demographics. Additionally, schools were asked about whether or not they had considered changing the school start times and perceived barriers to making the change. Results indicated that, on average, school start and end times did not change across the 15-year span from 1986–1987 to 2001–2002 (mean = 7:55 a.m.); however, early-starting schools reported increasingly earlier starting times over this period, whereas late-starting schools reported increasingly delayed bell schedules.25 Factors associated with earlier start times were higher socioeconomic status, urban environment, and larger student populations with busing systems that operate multiple routes at different times each day.25

In a now hallmark school transition study, Carskadon and colleagues assessed the impact of a 65-minute school start time advance across the transition from 9th grade (8:25 a.m.) to 10th grade (7:20 a.m.) for 40 14–16-year-olds attending a suburban, public school in the northeastern part of the US.7 In the spring of 9th and fall of 10th grades, assessments involved 2 weeks of actigraphy and sleep–wake diaries and an overnight laboratory evaluation that included dim light salivary melatonin and the Multiple Sleep Latency Test (MSLT). Actigraphic sleep records demonstrated that just over 60% of the 9th-graders and fewer than 50% of the 10th-graders obtained an average of 7 hours or more of sleep on school nights, and they awakened significantly earlier on school mornings, obtained less sleep, yet they did not go to sleep earlier in 10th than in 9th grade. In 10th grade, students’ DLSMO phase was significantly later and they also displayed atypical sleep patterns on the MSLT. For example, they fell asleep faster in 10th versus 9th grade, and about 50% of the 10th-graders experienced at least one REM sleep episode on the MSLT. Transitioning to an earlier school start time from 9th to 10th grade was associated with insufficient sleep and daytime sleepiness that is ordinarily seen in narcolepsy.47

Since the 1990s, researchers have examined the effects of school start times on adolescents’ sleep patterns and daytime functioning. Allen demonstrated that students from early- compared to late-starting schools reported shorter sleep times and a longer sleep phase delay.48 His own follow-up study indicated that students at an earlier-starting school (7:40 a.m.) slept less on school nights and woke up later on weekends than students at a later-starting school (8:30 a.m.).49 Moreover, later weekend bedtimes were associated with poorer grades in all students, with a higher percentage of students with ‘average grades’ reporting bedtimes after 2:30 a.m. in comparison to students who reported the highest grades. Another study that examined early-starting schools (7:20 a.m.) versus late (9:30 a.m.) found that students at both schools reported similar bedtimes, but students at the earlier-starting schools had shorter total sleep times and more irregular sleep schedules, which were also associated with poorer grades.50

Struck by Carskadon and colleagues’ laboratory school transition study, Wahlstrom and colleagues conducted a large-scale, convenience study in Minneapolis, Minnesota.5,7 Over 18 000 high school students in the Minneapolis School District were evaluated before and after the district delayed its high school start times from 7:15 a.m. to 8:40 a.m. beginning with the 1997–1998 school year.5,27 Wahlstrom and colleagues found the following: (1) attendance rates for students in grades 9 through 11 improved; (2) the percentage of high school students continuously enrolled in the district or the same school increased; (3) grades showed a slight but not statistically significant improvement; and (4) high school students, themselves, reported bedtimes similar to students in schools that did not change start times, obtaining nearly 1 hour more of sleep on school nights during the 1999–2000 school year.5,27 Similarly, Dexter and colleagues compared 10th- and 11th-graders attending late versus early-starting public high schools in the Midwest and found that adolescents at the late-starting high school reported more sleep and less daytime sleepiness as measured by the Epworth Sleepiness Scale.51 Htwe and colleagues surveyed high school students before and after their New England public school district delayed school start times from 7:35 to 8:15 a.m.52 As in previous studies, students reported sleeping, on average, 35 additional minutes and experienced less daytime sleepiness with the delayed high school start time.52

In a more recent study of 9th through 12th-graders at a private high school that instituted a 30-minute delay (from 8 to 8:30am), mean self-reported school night sleep duration increased by 45 minutes and mean bedtimes advanced by 18 minutes.4 The percentage of students getting less than 7 hours of sleep decreased by nearly 80% and those reporting at least 8 hours of sleep increased from 16% to 55%. Owens and colleagues also found that students reported significantly more satisfaction with their sleep, improved motivation as well as less daytime sleepiness, fatigue, and depressed mood following the delayed school start time.4 Health-related variables such as health center visits for fatigue-related complaints and class attendance also improved.4

Research on the impact of early versus delayed school start times for early adolescents has demonstrated strikingly similar findings. Specifically, 7th and 8th-graders at a later-starting urban middle school (8:37 a.m.) reported less tardiness, less daytime sleepiness, better academic performance (especially the 8th-graders), more school-night total sleep, and later rise times in comparison to middle school students at an earlier-starting school (7:15 a.m.) in the same district.26 A pilot study of 116 5th and 6th-graders attending early (7:45 a.m.) versus late (8:25 a.m.) starting elementary schools from the same large, urban New England district mentioned above found that students at the later-starting school reported later rise times, more sleep, and less daytime sleepiness than their pre- and early adolescent peers at the earlier-starting school.21 Likewise, Epstein and colleagues’ study of 811 10–12-year-olds from 18 Israeli schools with starting times that ranged from 7:10 to 8:30 a.m. demonstrated the importance of delaying school start times for pre- and early adolescents.53 Nearly 15 years ago, they compared schools that started at least 2 days per week at 7:15 a.m. or earlier with schools that started regularly at 8:00 a.m. Based on self-report, the pre- and early adolescents attending the early-starting schools obtained significantly less sleep (8.7 vs. 9.1 hours), complained more of daytime sleepiness, dozed off in class more often, and reported more attention and concentration difficulties than the students at the later-starting schools.53 Using an experimental design, Lufi and colleagues examined the impact of delaying middle school start time by 1 hour on sleep duration and attention in two groups of 14-year-olds.2 The experimental group was on a delayed schedule for 1 week and back on the original schedule for the second week of the study, while the control group kept their regular schedule for the 2 weeks.2 Participants’ sleep was estimated using actigraphy and attention was measured with two different measures of attention. In keeping with previous studies, during the delayed condition, the experimental group of middle schoolers slept nearly an hour longer and they performed better than the comparison group on tests requiring attention beyond practice effects.2 Undoubtedly, delaying the start of middle school allows early adolescents to obtain sufficient sleep and to perform better in school, similar to their older, high-school-aged peers.